Against the Current, No. 63, July/August 1996

-

Israel's Poisoned Fruits of Oslo

— The Editors -

Founding the Labor Party

— Dan La Botz -

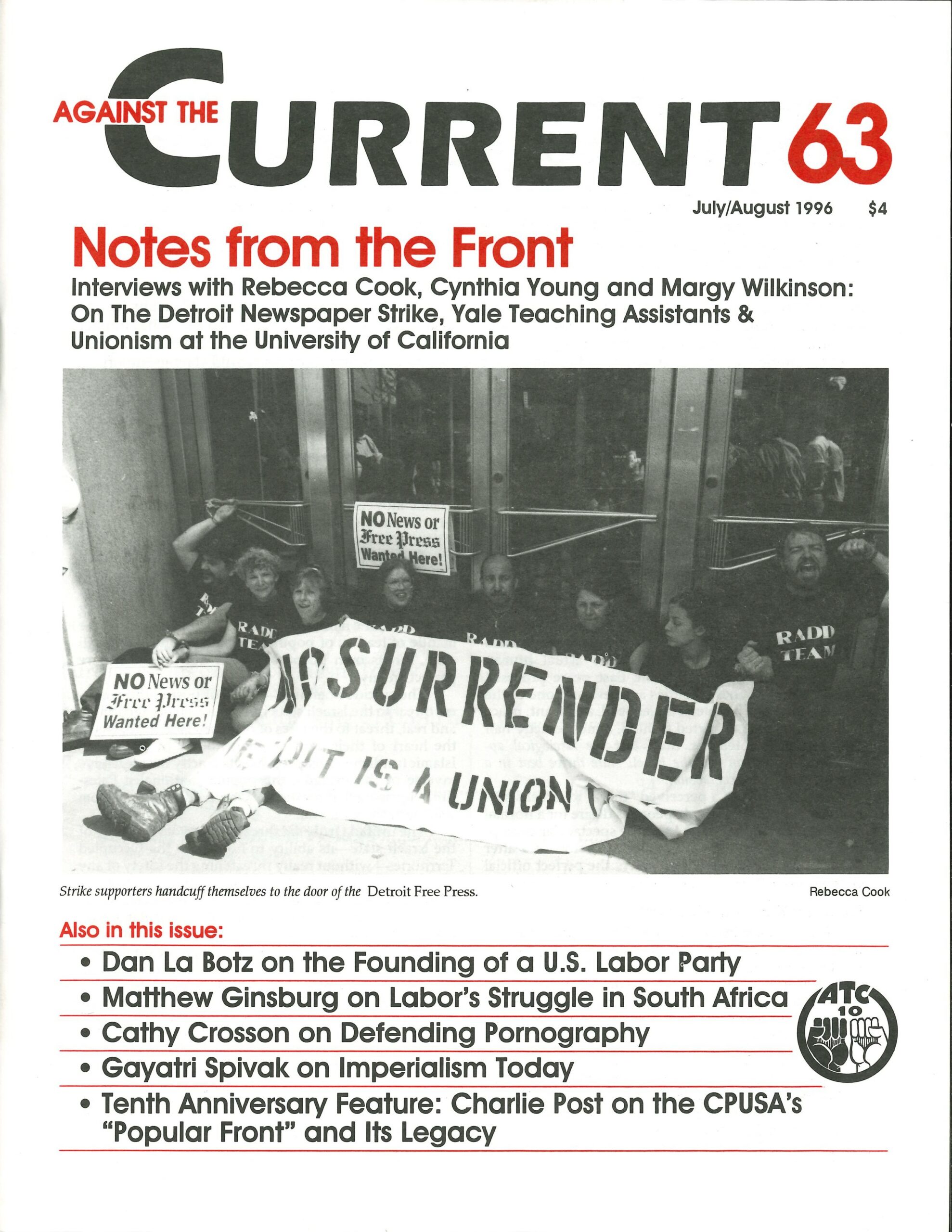

Detroit Newspaper Unions' Year of War

— interview with Rebecca Cook -

The Yale Grad Student Strike

— an interview with Cynthia Young -

A New Campus Union at University of California

— Claudia Horning interviews Margy Wilkinson -

The "Team Bill," A Poison Bill

— Ellis Boal -

Class and the African-American Leadership Crisis

— Malik Miah -

South African Labor Marching Again

— Mathew Ginsburg -

More on "Imperialism Today"

— Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak -

The Comintern, CPUSA & Activities of Rank-and-File CPers

— Charlie Post -

The Popular Front: Rethinking CPUSA History

— Charlie Post -

Queer Vows, Pros and Cons

— Catherine Sameh -

Radical Rhythms: "Global Divas"

— Kim Hunter -

Letter to the Editors

— Paul LeBlanc -

Random Shots: Wages and Other Minima

— R.F. Kampfer - Reviews

-

Pornography and the Sex Censor

— Cathy Crosson -

Reading Red Women Writers

— Renny Christopher -

The Uses of Dmitri Volkogonov

— Samuel Farber -

Trotsky Assassinated Again

— Susan Weissman

Mathew Ginsburg

ON MAY DAY 1986, the then recently formed Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) called a nationwide stay-away with the demand of employer and state recognition of Workers’ Day. The union movement’s first national strike since the 1960s marked the beginning of an era of intensified anti-apartheid struggle, which culminated in 1990 with the unbanning of popular organizations, the release of political prisoners and ultimately the beginning of the process of political settlement.

On May Day 1996, after four years of negotiation, national elections and then two years of a Government of National Unity (GNU), South Africa’s much heralded “transition to democracy” appears to have come to an abrupt end. As was the case ten years earlier, the labor movement has been intimately involved in recent events. Unlike the earlier revolutionary struggle against apartheid, however, present battles concern issues of development and entail challenging COSATU’s comrades in the African National Congress (ANC).

Having watched the ANC sabotage its own development plans during two years of government, COSATU faces difficult choices regarding its alliance with the ANC and its participation in state policymaking as it tries to locate a path to socialism. Up to this point, Cosatu’s decision has been to engage in an “inside-outside strategy,” in which corporatist engagements with the state and business are complemented by independent mobilization in civil society.(1)

For the South Africa labor movement, the key struggle in the

structural reform endeavor is the advocacy of meeting basic needs, as defined by the original Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP). This reform program has the potential to provide a connection between the labor movement and other sectors of civil society, open space for popular demands by decommodifying the reproduction of labor and aid in the development of class consciousness.(2)

The struggle for the implementation of the RDP must proceed hand-in-hand with the fight for workers’ control of their unions, the production process and state policy-making. As we shall see, the attainment of such goals is still far off two years into the ANC-led government.

The Constitutional Debate

April 30, 1996 marks the date of South Africa’s first national stay-away since the national elections, triggered by continued debate over clauses in the draft constitution regarding labor,education and property rights. In particular, unions were concerned about a proposed “Lock-Out Clause” which would diminish the power of workers to exercise their right to strike.

The battle over the constitution was heightened by a proposed property rights clause, which would hamper land redistribution, and an education clause, which would entrench the existence of white, Afrikaans-medium schools.

While the ANC publicly opposed the three offensive clauses, rumors circulated regarding the party’s preparedness to compromise in order to reach an accord with the National Party (NP), whose support was needed in parliament in order to win a strong mandate for the constitution. As the ANC’s resolve to oppose the clauses became increasingly shaky, COSATU leadership met on the night of April 21 to declare a stay-away for the last day of April if the passages were not removed.

Breakdown of the Armistice

The threat of a national strike has the effect of giving a healthy stir to an already boiling political cauldron. While the NP and other opposition parties accused COSATU of duplicity in making its submissions to the constituent assembly and then not abiding by the negotiation process, the ANC withheld its official support for the strike for several days, supposedly because the issue had not been properly discussed in the organization’s constitutional structures.(3)

In the meantime business, the media and even the International Monetary Fund used the opportunity provided by the coincidence of the strike call and the sharpening of a months’ long devaluation of the national currency to unleash the most vitriolic union bashing seen in this supposed period of reconciliation and partnership.

A careful observer of events in the two months leading up to the strike would have already noticed that the armistice that prevailed between government, business and labor had begun to break down. In late march, President Nelson Mandela announced a cabinet shake-up that, among other important features, closed the RDP office headed by ex-COSATU General Secretary Jay Naidoo. The RDP office was then downsized and moved under the domain of Executive Deputy President Thabo Mbeki, heir apparent to Mandela’s presidential throne and a notable member of an increasingly neoliberal wing within the ANC.

Such a move had been a long time in coming. The RDP, originally conceived of by COSATU as a social pact with the ANC to hold it to its pre-election promises once in office, was quickly transformed by the ANC in government into a catch-all rhetorical device that could be utilized as justification for neoliberal policy projects.

Starting with the RDP’s reformulation as a White Paper in 1994, the social demands of jobs, housing, health care, education and land reform were sacrificed on the altar of a fiscal deficit lower than recommended by the World Bank, real interest rates that rank among the highest in the world and a tariff reduction schedule more rigorous than that prescribed by GATT.

The current ANC reformulation of economic and social policy, a shadowy document called the “National Growth and Development Strategy,” continues the policy pattern set by the RDP White Paper. Copies of a leaked draft show a substantial continuity with the fate of the ever-weaker RDP, pairing promises of the delivery of basic goods with even more restrictive macro-economic policies.

The publication of policy proposals by both business and labor in the past months, however, has pushed to the breaking point the careful political balance maintained by ANC economic and social policy. In March, the South Africa Foundation, representing South Africa’s fifty largest manufacturers, tabled an economic policy document entitled “Growth for All” at the National Economic Development and Labor Council (Nedlac), South Africa’s tripartite economic policy body.

The document is a clear sign of business’ new ideological offensive, calling for the creation of a dual labor market, brisk privatization of state enterprises and a restriction of government social spending to the poorest of the poor.

On April 1, Nedlac’s labor delegation, made up of COSATU and two smaller federations, responded by tabling its first economic policy statement since its submissions on the RDP. “Social Equity and Job Creation: The Key to a Stable Future” revives the argument for “growth through redistribution” and goes some way toward discrediting the ANC’s neoliberal orthodoxy on fiscal, monetary and trade policy.

While this document is oriented more toward completing in the world capitalist economy than undermining it, “social equity” remains an important volley in widening South Africa’s constrained economic policy debate and undermining the ANC’s contradictory development discourse.

Effects of the Transition

Perhaps of more concern than the ANC’s undermining of the social content of the RDP is the dissolution of its emphasis on participatory “people-driven development.” While the original RDP document emphasized the role which civil society must play in grassroots development, and promised capacity-building assistance from the state, the RDP White Paper limited the definition of participation to labor’s involvement in Nedlac. Recent statements from ANC ministers go further in implying that the government may override even these limited consultative procedures in formulating an economic policy document.(4)

Unfortunately, the departure from participatory democracy seems to be spreading outward from government into civil society itself. The greatest flaw of labor’s “Social Equity” document lies not in its compromised content, but in the fact that few beyond top leadership were given access to it before public release, circumventing entirely the consultation, mandate and reportback procedures that are the hallmark of South African unions’ “worker control.”

Coupled with frequent tales of labor’s Nedlac negotiators taking decisions without proper mandates, it is a cause for concern that issues as important as economic and development policy are being decided without the participation of workers.

On issues closer to the shop floor, on the other hand, the continued strength of worker control is evident. In sectors such as auto, where cooperative deals of productivity for labor peace and wage increases have been struck, workers have ignored leadership intentions and engaged in unauthorized, “unprocedural” strikes.

Further, workers seem to be generally wary of the factory-level mechanisms of codetermination. Examples include Mercedes Benz, where 65% of shop stewards were not re-elected earlier this year because workers felt that they spent too much time with management and not enough on the shop-floor fighting for workers’ grievances.(5) Over 90% of shop stewards at Volkswagen were similarly replaced.

Academic and business claims to the contrary, experience lends strength to the argument that South African industry is still a long way from the stable state of “non-racial fordism” that is a prerequisite for the popular “post-fordist” measures of flexible production to go forward. For example, shop stewards responding last year to a nationwide survey regarding industrial relations responded overwhelmingly that their members primary concern was discrimination on the shop floor.(6) In the majority of factories the low-wage labor system, high-income differentials and institutionalized racism that were the hallmark of the apartheid era still persist.

Ironically, while shop-floor race relations continue almost unchanged from the apartheid era, the demographics of management are shifting at an unprecedented pace. The symbolic high point of this process was the April announcement by longtime COSATU leader, ANC general secretary and Constitutional Assembly chairperson Cyril Ramaphosa that he would retire his political posts to become Deputy Executive Chairman of New Africa Investments Limited (Nail). With the financial backing of a number of unions, Nail is attempting to buy a chunk of the Anglo-American conglomerate, which would make it the biggest Black-owned company in South African history.

The apparent inconsistency of the former National Union of Mineworkers leader suddenly switching to the other side of the bargaining table must be seen within the context of a shifting ideological terrain — in which Ramaphosa can declare on national radio that the benefits of Black-owned business will “trickle down” to the poor, while COSATU members shout “Love Live Comrade Cyril” at stay-away rallies in support of his role in Constitutional negotiations.

End of the Transition?

Despite all the mitigating factors against the unions, the April 30 strike was a success, if taken on the unions’ own terms. According to the unions, there was a 75% participation rate in the stay-away and over 200,000 workers participated in rallies in cities and towns throughout the country.(7)

More importantly, the final draft of the Constitution submitted to Parliament a week later contained no mention of the lock-out clause, instead recognizing the right of consultative bodies to decide on the matter. Similar favorable compromises were struck with the NP on the clauses regarding education and private property.

The mess from the post-Constitutional party had barely been swept up, however, when the political repercussions of the event became apparent. Only a few days after the Constitution’s completion, Deputy President F.W. De Klerk announced that the National Party was withdrawing from the Government of National Unity in order to fight more vigorously as an opposition. While there is a chance that COSATU will wield more influence on decision making now that the ANC can no longer deflect blame onto the NP, early signs indicate a sense of political continuity.

Looking Forward, Looking Back

The processes of economic globalization and the decay of the alternative paths of third-world economic nationalism and state socialism have had devastating effects, both materially and ideologically, on a mass democratic movement that just a few years ago was considered the best hope for the left in the late twentieth-century.

The South African labor movement’s chosen path towards socialismhas been seldom travelled, and is fraught with the dangers of cooptation, yet must still be considered seriously. The great challenge to South African workers now is to widen and deepen the scope of mass struggle, utilizing the forms of action that were born in 1986 to take advantage of opportunities only present in 1996.

Deepening struggle requires a focus on unions’ traditional power capacity, worker organization and mobilization at the point of production, as well as the development of capacity for involvement of workers in policy development and implementation.

In order to widen the struggle, workers in the South African labor movement must build strategies to bring other sections of civil society into a joint socialist project. Fortunately, there are signs that these things may be beginning to happen.

Judging from recent events, it appears that mobilization against elite government development plans is growing. For example, in response to threats of privatization, including President Mandela’s recent statement that “Privatization is the fundamental policy of the ANC,”(8) a coalition of unions led by some of Cosatu’s weaker affiliates have come together to try to build consensus and momentum around a national strike for July 1.(9)

Ironically, this news arrived the same day as COSATU General Secretary Sam Shilowa announced that COSATU was open to partial privatization of small, non-strategic enterprises.(10) These events can be read either as COSATU affiliates bucking the liberalizing trend of its leadership, or as a tactical move at the top to open space for maneuver while forces on the ground prepare for action.

In either case, the announcement of mass action comes as a welcome sign. There are also signals that the labor movement is on its way towards the complementary goals of building union strength, solidifying ties with civil society and creating an alternative path of economic development.

In particular, a union-driven campaign for “Affordable Housing for All” has been discussed recently. Such a campaign would aim to decommodify a key factor of labor reproduction and cement ties with popular organizations like the South African National Civics Organization (SANCO), while providing a job-creating boost to the economy.

Worker-driven mobilizations against privatization and for universal housing provision would go a great distance toward clarifying COSATU’s political role as a member of the tripartite alliance and demystifying the contradictory development discourse promoted by the ANC. By forcing the ANC to take a stand on privatization,”Affordable Housing for All” or similar programs, COSATU might force the government back into a participatory alliance, at which point labor could move forward to extract further demands.

Alternatively, the ANC’s failure to support such a program would further reveal to South Africans the full consequences of the government’s shift toward neoliberalism — thus, perhaps, placing the idea of a workers’ party more firmly on the agenda.

Notes

- This path corresponds broadly with John Saul’s theory of “structural reform,” a mode of struggle defined by battles for reforms which “self-consciously implicate other ‘necessary’ reforms that flow from it as part of an emerging project of structural transformation.” In Saul’s telling, these reforms much emerge from the base of mass movements through processes of construction of class-consciousness and the building of organizational strength.

back to text - [Some of the potential and ambiguities of the RDP were discussed in essay by Patrick Bond and Moses Mayekiso appearing respectively in ATC 50 and 51, May-June and July-August, 1994–ed.]

back to text - Grawitzky, Renee, “ANC still ‘to decide’ on support for strike,” Business Day, April 23, 1996, 2.

back to text - For example, Mboweni, Tito, “Laboured Relations,” The Star, May 23, 1996, Business Report, 4.

back to text - Interview with NUMSA local organizer from Mercedes Benz of South Africa, May 20, 1996.

back to text - Grawitsky, Renee, “Research may put unions in new light,” Business Day, May 3, 1996, 6.

back to text - “COSATU May Day call: Step up mass actio0n,” The Star, May 1, 1996, 1.

back to text - Loxton, Lynda, “Mandela: We are going to privatise,” The Saturday Star, May 25, 1996, 1.

back to text - Bell, Terry, “Arming the Unions,” The Star, May 24, 1996, Business Report, 3.

back to text - Volschenk, Christo, “COSATU opens a door to partial privatisation,” The Star, May 24, 1996, Business Report, 1.

back to text

ATC 63, July-August 1996