Against the Current, No. 62, May/June 1996

-

Ten Years of Against the Current

— The Editors -

How Labor Loses When it "Wins"

— Peter Downs -

Yale Workers Fight the Power

— Gordon Lafer -

Brazil's Workers Party Redefining Itself

— Michael Shellenberger -

Modern "Gunboat" Diplomacy in the Caribbean

— an interview with Cecilia Green -

"Burn the Haystack!"

— News From Within -

The Clinton-Helms-Burton Travesty

— The ATC Editors -

The IMF Restructures Sri Lanka

— D.A. Jawardana -

Chandrika's "Great Victory"

— Vickramabahu Karunarathne -

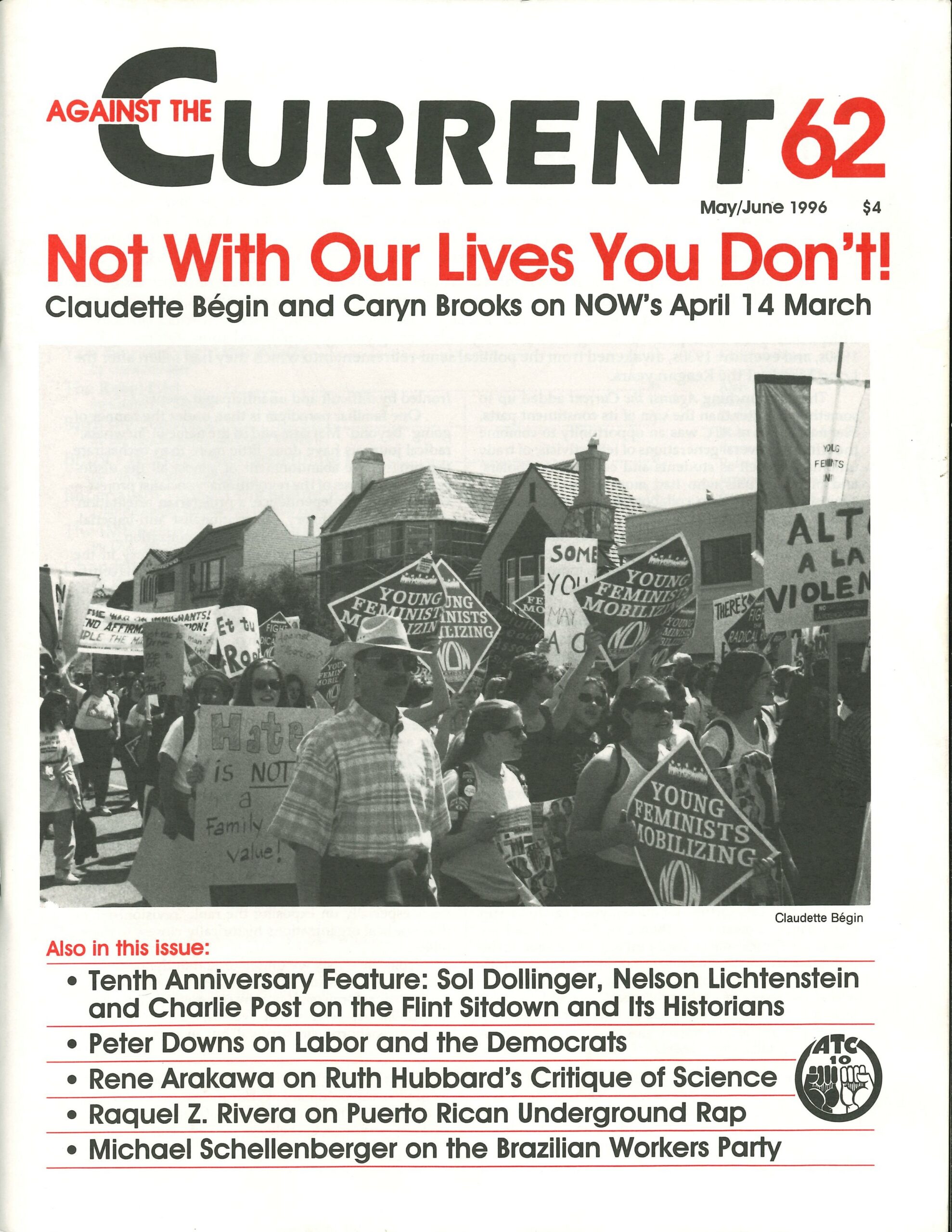

Getting It Right About Now

— Claudette Begin and Caryn Brooks -

Fight the Right

— Claudette Begin -

Ruth Hubbard's Feminist Critique of Science

— Rene L. Arakawa -

Reclaiming Utopia: The Legacy of Ernst Bloch

— Tim Dayton -

Policing Morality: Underground Rap in Puerto Rico

— Raquel Z. Rivera -

Answering Camille Paglia

— Nora Ruth Roberts -

On Being Ten

— Greetings from Our Friends -

Letters to the Editors

— Peter Drucker; Linda Gordon - The Great Flint Sitdown: An ATC 10th Anniversary Feature

-

Introduction: The Flint Sitdown for Beginners

— Charlie Post -

The Rebel Girl: The Real Threat to Life

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Politics, Religion and Mad Cows

— R.F. Kampfer -

Flint and the Rewriting of History

— Sol Dollinger -

Politics and Memory in the Flint Sitdown Strikes

— Nelson Lichtenstein - Reviews

-

McNamara's Vietnam

— Lillian S. Robinson -

Ken Saro-Wiwa's Antiwar Masterpiece

— Dianne Feeley -

Statement to the Court

— Ken Saro-Wiwa - In Memoriam

-

Marxist Art Historian: Meyer Schapiro, 1904-1996

— Alan Wallach

Michael Shellenberger

AT THE BRAZILIAN Workers Party (PT) convention last August, president Luiz Ina’cio Lula da Silva used his opening speech to denounce, with unionist bravura, the elitism that has accompanied the party’s electoral successes since it was founded in 1980.

Some within the PT seem seduced by the perfume of the elites and can no longer stand the smell of the people. They prefer carpeted rooms to rural settlements, official cars to the factory gates, TV studios to the alleys of the neighborhoods. They do politics as a profession and not as a means to end injustice.

He paused, looking into the rapt assembly of PT delegates, journalists and visitors. “I’ll repeat what I said in 1981, at the first National Party Convention: the day that leaders of the PT can no longer go to the factory gates, the workplace, or to where workers are fighting for the land, it’s better to close the PT.”

The August party convention was held amidst generalized bad feelings over Lula’s 1994 defeat and a growing divide between the leadership and the grassroots. Founded as a revolutionary and socialist party in 1980, Brazil’s PT is the most powerful left-wing organization in Latin America today. Workers Party mayors govern 50 cities and four major state capitals. Its legislative block of 49 deputies and five senators, though hopelessly outnumbered in the national congress, maintains an articulate and combative left presence. The vast majority of activists at the grassroots, from urban unions and popular movements to the Landless Peasant’s Movement (MST), are either members or sympathizers of the PT.

Yet this base has become increasingly disenchanted with what it sees as evidence that the party has lost the mi’stica that animated its heady early years. Some point to 1989, the year Lula was nearly elected president and national power seemed within reach, as a key turning point. Since then Lula has moderated the PT’s radical discourse, contained the power of left-wing tendencies and pushed the party toward participation in elections and government. Yet within the party Lula maintains an image of being sal da terra – salt-of-the-earth, even among grassroots activists who feel snubbed by the party’s “professionalization.”

Lula’s following is certainly understandable: no other working-class leader in Latin American history has united electoral and popular struggles with greater success. Like Mahatma Gandhi, who Lula cites as a major inspiration, the former metal-worker is committed to local political organization and nonviolent mobilization. Also like Gandhi, Lula is a strong leader who appears uncontaminated by the trappings of power. On the final day of the August convention Lula punctuated his commitment to the rank and file by retiring from the presidency.

In a July interview, Lula told me he will use his retirement to “reorganize the party and civil society” from the bottom up. As during his 1994 campaign for the presidency, Lula has begun a series of road caravans to meet with local organizations and address local concerns.

Lula’s popularity was, for many years, the glue that held the PT together, so it’s understandable that selecting a new party president would be controversial. Ze’ Dirceu, Lula’s hand-picked successor, has neither the charisma nor the national presence of his mentor. And for the party’s left wing, the election of former federal deputy Dirceu is further proof that the PT has substituted its socialist vision for a social-democratic practice.

Pandemonium Breaks Out

But because Lula and the national leadership had secured Dirceu’s victory before the convention, few expected the pandemonium that erupted before the delegates voted on last day, August 21. During the final debates among the general assembly, Ce’sar Benjamin, former political prisoner and member of the left-wing “Hour of Truth” tendency, stood up and repeated what was known to most yet mostly ignored throughout the convention: that Dirceu accepted half a million dollars in legal but ethically questionable donations from the Norberto Odebrecht Construction firm to finance his Sao Paulo gubernatorial bid last year.

Benjamin’s denunciation outraged the delegates who filled the auditorium. Lula, Dirceu, and much of the executive leadership burst into tears. Senator Eduardo Suplicy shouted “You want to destroy the PT!” and an angry mob threatened to assault Benjamin, who, protected by party security, was forced to take refuge in a corner of the auditorium.

Members of Benjamin’s own tendency and Hamilton Pereira, the only other candidate for the presidency, went to the podium to defend Dirceu, and for the first time at a party convention Lula made an eleventh hour speech endorsing his candidate. With fifty-four percent of the votes, 215 to 183, Dirceu won the presidency.

Most party activists I spoke with said the time and place of Benjamin’s denunciation was “inappropriate” but also expressed concern that the PT (including Lula’s presidential campaign) accepted money from Odebrecht, which is infamous for its involvement in major corruption scandals.

Ironically, Dirceu is known among the press and within the PT for his active participation, as federal deputy, in a 1993 investigation into influence-peddling rackets between members of the congressional budget committee and major construction firms. Odebrecht, the most prominent of the contractors, has since become synonymous with what economists refer to as Brazil’s uniquely “savage capitalism.”

The Odebrecht donations became public when the local branch of the PT in the national capital, Brasi’lia, decided to return the money. Later, the regional Sao Paulo leadership called its acceptance of Odebrecht money a political mistake.

“Negotiations with the enemy should be done openly and publicly,” argued Ali’pio Freire, former editor of Teoria e Debate, the PT’s sophisticated theoretical magazine. “You can’t accept money from a contractor and expect him not to demand something in return.”

Two months after the August convention, Dirceu played down any conflict of interest. “There is no relation between the money we received from contractors and our criticisms, investigations, and legal actions against them,” he told me. The national PT leadership will establish criteria to “discriminate against donations from particular businesses.” When I asked if the PT would accept Odebrecht money in the future he didn’t rule out the possibility. “That has to be discussed by the national leadership.”

Where Are the Party’s Roots?

The larger question raised by the Odebrecht incident is whether the PT can participate in elections which are privately funded without abandoning its high ethical standards and commitment to building a mass movement.

Carlos Bele’, a national leader of the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST), said “the problem is that the party has lost its roots.” Strongly tied to the PT since its founding in 1985, the MST is the largest independent peasant movement in Latin America.

The MST leadership, which continues to advocate socialist revolution, is disturbed by the PT’s “reformist” turn. “The PT has become a social democratic party like that of 1960s Europe,” Bele’ complained.

Some argue that the PT’s emphasis on winning elections has led to globalized demobilization. According to Rio de Janeiro community activist, Maria Luisa da Rocha, “Before, the PT was the grassroots movement. It advocated for the neighborhoods and civil rights. Now we’re in a state of total bureaucratization.”

Criticism is coming from activists who feel they laid the groundwork for PT electoral victories yet feel excluded by the upper echelon party members who run the election campaigns and advise the politicians. For Gersom Beuter, a former trade unionist and a co-founder of the party in Porto Alegre, the leadership has become too middle-class, too intelectualizado. “Before things were run by the workers, by guys in overalls,” he growled. “Now the leadership’s all university educated. Soon we’ll have to set quotas to guarantee that a third of the party leadership is from the working class!”

A popular stereotype holds that the PT is always on the verge of breaking up due to the warfare between various ideological factions organized into tendencies. Today this perception is only partly true. According to former Maranhao state PT president Chico Goncalves, “tendencies used to be organized along ideological lines but now are grouped more around particular personalities, so much so that a lot of people think, ‘I can’t criticize this or that party candidate because some day he may be elected and could deny me a job.'”

According to journalist Freire, who was a former urban guerrilla imprisoned from 1969 to 1972, “the party cells are being substituted by direto’rios, local party headquarters. The cell today is much more rhetoric than reality. Every guerrilla manual says you must bring the enemy into your territory. We do just the opposite: we go to congress. The struggle cannot just be institutional.”

When I repeated back these criticism to Dirceu, he bristled. “What do they want the PT to do? Not dispute elections? The PT has grown a lot in fifteen years. In the beginning it was a party of union and social movements. Then we won congressional seats, state governments, and almost the presidency. Society should be organized to control the state and we have to prove ourselves to Brazilian society by governing. To think that the PT should be a movement for the movement’s sake! That’s an entirely backwards notion of politics.”

Dirceu points out that the “institutional struggle” was of critical importance to the PT’s (and Brazil’s) largest mobilizations of the past ten years: the 1985 movement for direct presidential elections against the dictatorship, Lula’s 1989 presidential campaign, the 1986-88 Constitutional Assembly, and the 1992 movement to impeach President Collor for his blatant corruption.

Porto Alegre’s Innovative Budget

It is understandable both that local PT governments would hire staffs of qualified professionals and that some within the party would be resentful. Though Beuter complains, he still supports Tarso Genro, Porto Alegre’s erudite PT mayor, who also has the approval of seventy-two percent of city residents. As the mayor of a relatively wealthy southern capital of 1.3 million, Genro benefits from Porto Alegre’s small size and a politically active union and popular movements.

PT local governments are widely credited for having deepened the relationship between city hall and the neighborhoods. Porto Alegre’s “Participatory Budget” is innovative in that it incorporates neighborhood organizations and popular movements into the planning and allocations process.

Community leaders are elected as “counselors” to determine what their neighborhoods want and to monitor city projects from beginning to end. In addition, there are popular councils that allocate and oversee road construction, sewage, transportation, health, taxation and education.

Porto Alegre is used as a model by PT and non-PT mayors throughout Brazil and, when I interviewed him in July, Mayor Genro had just returned from Germany where he gave presentations on the Participatory Budget to local governments. “The Participatory Budget breaks with the myth that the people are destined to be dominated by the ruling class,” he said confidently.

Public participation in city hall also serves to root out widespread corruption and create a “culture of transparency” within government. I asked former counselor, Gilmar Sander, elected from the poor outskirts of the city in 1993, about the history of the Participatory Budget.

“When it first started,” he explained, “folks were skeptical. They thought the mayor was trying to buy votes for the next elections. But little by little, people started getting involved, especially after they started to see the results. To given you an idea, before the city would end up paying $500,000 for a job that should have cost $100,000. Now the communities watch over the money from beginning to end.”

Though entirely eliminating corruption from city government is probably impossible, the Participatory Budget has become such a part of public life that major kick-back schemes routine most everywhere else in Brazil are next to impossible. Journalists at Zero Hora, the city’s conservative daily, were hard pressed to remember any corruption scandals since the first PT mayor was elected in 1988. In a news search the best we could find was an investigation initiated by an opposition councilman, soon dropped for lack of evidence.

Privately, city officials boast that the elimination of kick-backs from contractors to government bureaucrats has earned the respect of the business community. When the Secretary of Industry and Commerce, Jose’ Luis Viena Moraes, and his staff determined that a recently built shopping mall would jam traffic downtown, they asked the contracting firm to put up the money to widen the adjacent avenue. “To our surprise they agreed immediately,” Moraes said. “The executives told us that they had already set aside tens of thousands of reais to lubricate their dealings with the mayor’s office and that they would much rather invest the money in the city.”

In the context of Brazil, which sets the benchmark for corruption in Latin America, what the PT has accomplished in Porto Alegre is nothing short of revolutionary. By involving the citizenry through its Participatory Budget and investing in social services, the PT may not have started Porto Alegre down the path toward socialism but it did reduce significantly infant death, hunger, malnutrition and crime.

The PT’s Need to Win the Presidency

Tarso Genro and the mayors of other PT governed cities are quick to point out the limitations of their office. Only through winning the presidency, they say, will the PT be able to implement a national economic development plan to raise the standard of living for Brazil’s poor majority. That opportunity was lost once again last year when Lula was defeated a second time in his bid for the presidency.

Four months before the October 1994 elections, the Brazilian government implemented an anti-inflation plan and its author, presidential candidate and former Finance Minister Fernando Henrique Cardoso, raced ahead of Lula in the polls to win with fifty-five percent to Lula’s twenty-seven percent of the vote. Several months earlier Cardoso had signed a pact with the Liberal Front Party (PFL), a right-wing band of big landowners and industrialists.

As the official puppets of the military dictatorship (1964 85), PFL leaders are traditional parasites of the State, experts at appropriating public wealth through the distribution of government contracts and jobs and elaborate kick-back schemes (with Odebrecht, for example). Now, after decades of cutting themselves tax breaks, easy credit and subsidies for industry and agriculture, the PFL speaks of liberalized markets and efficiency with the same determination (and sincerity) of World Bank technocrats. Most of all they are clamoring for rapid privatizations, and the reason is clear: as in Mexico, the President’s allies stand to make a killing, buying up state industries for appallingly low prices.

Alongside the outright privatizations, Cardoso succeeded in modifying the constitution to allow private competition, mostly by multinational corporations, in lucrative oil and telecommunications markets that have been monopolized by the state since the fifties.

For four decades, state industries have been managed by political appointees whose allegiance is to elected officials that historically have used the industries to further their own personal and political objectives. Decapitalized and defrauded, the state oil and telecommunications industries are far less efficient than their multinational counterparts. Once they face competition from the likes of Exxon and AT&T there is little doubt that they will be forced to lay-off thousands of workers and give-up market share to survive.

“The break-up of the oil and telecommunications monopoly is an historic error,” Lula told me. “Just because these industries have some problems doesn’t mean we should turn over our public wealth and the power to determine prices for strategic goods to big business. We’ve abandoned a state monopoly for a private monopoly.” By opening up oil and telecommunications markets to foreign competition, Lula contends, Brazil is turning public control of national development over to foreign investors and multinational corporations.

But given that the PT is greatly outgunned in the congress and the next national elections won’t be held until 1998, Lula will have to rally the grassroots and PT allies if he hopes to slow down the Cardoso-PFL machine. For Rio de Janeiro church and PT activist, Ce’sar Silva, “Neoliberalism has emerged even among us. To beat it we’ll need to become part of popular culture again.” Toward that goal, Lula and the PT must find new links to narrow the chasm that separates the party grassroots from the electoral bureaucracy.

Though only 49 years old, Lula says he is very tired after twenty-two years as a union leader, fifteen with the PT. When I asked if he still feels impatient, Lula took the long view of social change. “It’s important to remember that we have a tradition of armed revolutionary struggle in Latin American and have only recently have begun the process of democratic struggle,” he said, pausing to relight his cigar. “A party like the PT can’t be in a hurry, we can’t lose our serenity.”

ON MARCH 20, 1,100 Yale University custodians, plant maintenance and dining hall workers walked off the job. With 97% of the workforce participating in this strike, all but one of Yale’s dining halls shut down; trash began piling up; managers are being paid $35/hour to scrub toilets.

ATC 62, May-June 1996