Against the Current, No. 59, November/December 1995

-

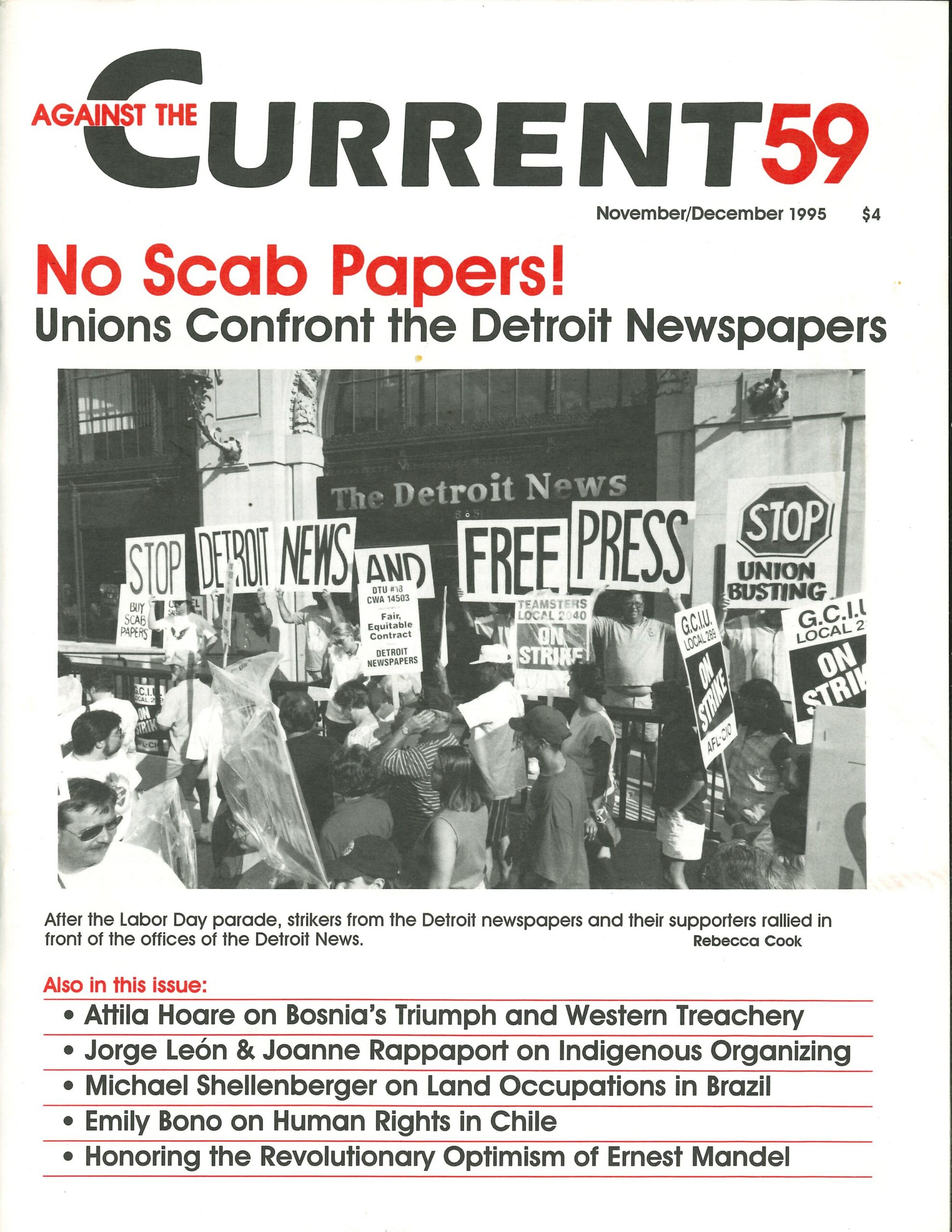

Labor Wars, from Top to Bottom

— The Editors -

The Detroit Newspaper Labor War

— David Finkel -

Potrait of a Strikebreaker

— Roger Horowitz -

Bosnia's Triumph and Western Treachery

— Attila Hoare -

Radical Rhythms: World Music--What in the World Is It?

— Kim Hunter -

Letter to the Editor--and Reply

— Michael Funke; Archie Lieberman -

The Rebel Girl: The Complexities of Inclusion

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Bad Cop! No Donut!

— R.F. Kampfer - A Symposium on Imperialism Today

-

Introduction

— The Editors -

The Shape of Today's Imperialism

— Kim Moody -

Myths of "Humanitarian" Intervention

— Michael Parenti -

Imperialism with a Human Face?

— Paul Le Blanc - Organizing in the Americas

-

Haiti: The Elections and After

— Dianne Feeley -

Chile: The Human Rights Challenge

— Emily Bono -

Land Occupation and Struggle in Brazil

— Michael Shellenberger -

Amazon Peasant Massacred

— Michael Shellenberger -

Forced Labor in Brazil: An interview with James Cavallaro

— Marcelo Irajá de Araújo Hoffman -

Indigenous Organizing in Colombia and Ecuador

— Jorge León and Joanne Rappaport - Reviews

-

Uncracking Crack Coverage

— Janice Peck - In Memoriam

-

Ernest Mandel: A Passionate Optimistic Marxist

— Anwar Shaikh -

Ernest Mandel: Internationalist and Dear Comrade

— Rosario Ibarra de Piedra -

In Tribute to Ernest Mandel

— Andre Gunder Frank -

Ernest Mandel: Revolutionary of the 20th Century

— Manuel Aguilar Mora -

Ernest Mandel: A Revolutionary Heroic Life

— Jacob Moneta -

Hedda Garza, 1929-1995

— Patrick M. Quinn -

William Kunstler, 1919-1995

— Michael Steven Smith

Anwar Shaikh

ERNEST MANDEL WAS an extraordinary man in an extraordinary age. We are here to honor him for his passionate espousal of marxism, for his deep and abiding concern with struggles against oppression, for the breadth of his knowledge, for the rigor of his intellect, and for his ability to acknowledge the world that is while continuing to fight for the world that could be.

No life is free of mistakes and heartaches. But some remind us that a life can be lived with ideals, passions, and actions fully connected to each other. We are here to celebrate a man who lived such a life.

We live in an era in which capitalism seems to have swept away all barriers to its global hegemony. We are told again and again that there is no alternative, that nothing works as well as capitalism. And then we are told, in the same breath, that it does not work very well after all.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) finds that some thirty percent of the world’s population is unemployed or underemployed–forty percent if one focuses on the third world. Newspapers point out daily that profits are high, wages low, and mechanization proceeding so rapidly that most labor may be redundant in the foreseeable future.

That is, of course, the good news. But there is bad news also: The business failure rate remains high, exchange rates gyrate in dangerous and unpredictable ways, wars and revolts simmer and bubble all over the globe, and by all accounts the international monetary system is sitting on the financial equivalent of an earthquake fault–with Japan, that glorious example of all that is said to represent the very best in capitalism, at the very epicenter.

To quote the Economist: “The biggest risk to world economic stability now is a financial collapse in Japan.” (June 17, 1995; 76) Then there is of course continuing and widespread environmental devastation, the hole in the ozone layer and the high probability of global warming and its disastrous consequences.

The System’s Inner Dynamic

Is this truly all there can be? Ernest Mandel dedicated himself to arguing that a better way of life is not only imaginable but achievable. Much has been said so far about the political impact of his ideas and his practices, and there is more to come of these aspects of his lifework.

For this reason, I would like to dwell instead on his intellectual contribution to an absolutely fundamental issue in the struggle against capitalism: the analysis of its own internal dynamics, of the forces that drive it to dizzying new heights only to bring it back down to new lows–the analysis, in other words, of capitalism’s internally generated laws of motion.

In the heady period of the great postwar boom, with the United States apparently firmly in charge of what was then a new capitalist world order, then too it seemed that capitalism’s future looked unlimited. Indeed, by the 1950s it was a standard claim that the so-called Keynesian revolution had discovered the practical tools by which to regulate capitalism, to steer it toward socially desirable ends.

The “reserve army of unemployed” could be abolished by policies designed to maintain high employment, the business cycle tamped down by countercyclical measures, and poverty eliminated by policies of the welfare state.

Return of the Crisis

My own experience provides a good illustration of the manner in which this climate was reflected in academic halls. I entered graduate school at Columbia in the Fall of 1967. This was a period in which Daniel Bell’s book The End Of Ideology (1967) had made a considerable impact, at least in intellectual circles.

At the first meeting of all graduate students, we were greeted by the chair of the Economics Department. He congratulated us on our admission into the esteemed ranks of the university. He spoke about the importance of our profession, and about our personal glowing prospects.

And then he ended with a most curious footnote: He confessed that in spite of all this, he felt sorry for us, because all the basic problems of economics had already been solved! There were many details to be worked out, of course, but nothing of great importance left to be discovered in economics.

The world was on track, and the academics were on top of things…Less than nine months later in the Spring of 1968 came the Paris students’ revolt, the Mexican students’ revolt, and even the Columbia students’ revolt in which I and many others occupied buildings, including the very one in which the chairman’s words had been pronounced.

1968-70 marked the turning point of the long postwar boom, and the beginning of a series of economic and political troubles that continue to this very day. That old illusory order, at any rate, fell apart remarkably quickly.

Marxist Renewal

It must be stressed that for a while postwar capitalism did make important progress in containing and channeling capitalism’s worst aspects–at least in the advanced capitalist countries. But the claim made at the time was that Keynesian economics had made all other understandings of capitalism obsolete.

In particular, as Mandel points out, Marxism was said to be one of many outmoded schools of political economy that had failed to keep up with new developments in capitalism and in its analysis. (Marxist Economic Theory, 1968; 15)

Mandel’s first major work was written in this climate, and was aimed precisely at this claim. The French edition of Marxist Economic Theory (MET) appeared in 1962, and the English one in 1968. What is most striking about this work is that Mandel begins by noting that the critics of marxism are largely right! I quote:

“Those who claim to be Marxist are themselves partly responsible for the decline in interest in Marxist economic theory. The fact is that, for nearly fifty years, they have been content to repeat Marx’s teaching, in summaries of Capital which have increasingly lost contact with contemporary reality …Marxists [have been unable]…to repeat in the second half of the twentieth century the work that Marx carried out throughout the nineteenth.

“This inability is due above all to political causes. It results from the subordinate position in which theory was kept in the USSR and in the Communist Parties in the Stalin era…[and in a corresponding tendency in the West which either] restricts itself to summarizing…the chapters in Capital written in the last century…[or else dismisses this same material] ‘because it relies on the data of the science of last century.” (MET, Vol. I, 15-17)

Mandel does not say here, but it must be said, that there were already other notable exceptions: Michal Kalecki, Maurice Dobb, Paul Sweezy, Paul Baran, Paul Mattick and Harry Braverman.

Yet by comparison with these authors, Mandel set himself an enormous task: nothing less than to “show that it is possible, on the basis of the scientific data of contemporary science, to reconstitute the whole economic system of Karl Marx and that in so doing it is possible to provide a synthesis of economic history and economic theory” (MET, Vol. I, 17)

Characteristically, he explicitly attempts to encompass not just Western but also non-Western experience and history, for he was always and everywhere a true internationalist.

From Basic Foundations to Automation

In his two-volume MET Mandel spans an extraordinary range of topics. He begins with the very nature of society, communication, language, consciousness and humanity, and with the importance of social labor–that is, labor in-and-through a social context–in providing the foundation of a social community.

From this he moves successively to the historical development of exchange, of commodities and their valuation, of the rise of money and then of capital, of the development of capitalism itself, of its internal contradictions, of its external trade, of its historical transformation into monopoly capitalism with its own specific patterns and contradictions, of imperial<->ism and neoimperialism, of the Soviet economy and its own contradictions, of the potentials and problems of the modern surge in mechanization (which he calls the third industrial revolution), and in the end, of the potential and promise of a genuine socialist economy founded on an “abundance of goods and services” (655-666).

He draws on an extraordinary range of scientific research in anthropology, sociology, political science, history, finance, business, statistics, economics and other disciplines, published in English, German and French, by writers all over the world.

There are many striking passages in this monumental work; I have time to cite only one, on the issue of automation. As I read it out, recall that it was written in 1962!

“The number of workers engaged in production is falling both relatively, and sometimes absolutely…Moreover, the third industrial revolution substitutes machinery for mental work. . . Office workers, accountants, checkers are being replaced…by electronic computers . . . Technocrats even envisage the creation of a society from which [workers]…will be completely eliminated . . .

“The third industrial revolution can thus lead either to plenty or to the destruction of freedom, civilization and humanity. In order to avoid the worst, the use of automation must be subject to conscious control…The productive forces released by the third industrial revolution must be tamed, made tractable, civilized, by means of a world plan of economic development. They must bring about the conscious management of human affairs, or in other words, a socialist society.” (MET, 608)

Evolution of Ideas

In this work Mandel continually stresses the importance of “the study of empirical data, the raw material of every science,” as well as of the study of the ideas of others writing on the same or related subjects.

As he emphasizes throughout, this way of proceeding is a critical aspect of marxist research. And in his next major work in economics, The Formation of the Economic Thought of Karl Marx, he proceeds to illustrate just how important this process was in forming Marx and Engels’ own ideas on economics.

Mandel stresses the evolution of their ideas, emphasizes that their early brilliance was still hampered by a lack of empirical knowledge. (Formation, 23)

He shows that Marx initially rejected the labor theory of value but then subsequently adopted and transformed it. On the other hand, Marx initially accepts the notion that wages must fall absolutely over time, then subsequently rejects it in favor of the notion that they fall relatively–i.e. that the rate of surplus value rises over time.

All this is designed to show that, like any great scientist, Marx constantly developed and deepened his understanding of capitalism, and corrected and refined his ideas. Given that Marx’s mature works in Capital Volumes II and III appear to us in so fragmented a form, Mandel performs a great service by tracing through the development of his economic ideas.

Late Capitalism

It is in his Late Capitalism (1992, 1975) that Mandel comes into his own as a major analyst of modern capitalism.

He moves brilliantly and confidently “to provide an explanation of the history of the mode of production in the 20th century”–not just as a history or a set of empirical patterns, but rather as exemplifying how the general laws of motion of capital manifest themselves in “concrete phenomenal form.” (LC 1975, 9)

In so doing Mandel places himself squarely in the tradition which Perry Anderson has called Classical Marxism. In this approach, which begins with Marx, capitalism is seen to generate fundamental patterns, which are rooted in the profit motive itself and therefore part of its “genetic” signature.

These laws of motion include the workings of the law of value, the worldwide creation and maintenance of a reserve army of (unemployed) labor, the intrinsic drive within capitalism to mechanize all forms of labor, and the recurrence of long alternating phases of boom and stagnation.

Capitalist institutions and epochs give these particular historical expression, but they neither create these laws nor can they abolish them. The capitalist state too operates within these laws, modulating these but remaining subject to their limits.

Only by abolishing their root cause–the dominance of the profit motive, and hence the dominance of capitalist relations–can their outcomes be abolished.

Late Capitalism is a work that brilliantly develops the themes found in Man<->del’s previous works. Writing in 1970-72, he seeks not only to explain the long postwar boom that lasted into the early 1970s, but also to show that this boom is subject to “inherent limits . . . which ensured that it would be followed by another long wave of increasing social and economic crisis for world capitalism, characterized by as far lower rate of overall growth.” [LC 1975, 8]

There are fascinating and important discussions of the relation between laws of motion and actual history, of the structure of the capitalist world market, of the acceleration of technological innovation through the ever more “systematic application of science to production” (248), of the thesis of unequal exchange and its implications for uneven development, of the roots of modern inflation in private bank credit and not merely in the budget deficits of the state, of the roles of the state and of ideology, and of the recurrence of long waves throughout the history of capitalism.

Long Waves

The notion of long waves plays a particularly important role in Late Capitalism, since it provides a basis for his early prediction of the subsequent period of stagnation and crisis. Further developments on this theme are presented in his books The Second Slump (1977, 1978) and Long Waves in Capitalist Development (LWCD, 1980 and a newly revised edition in 1995), and in his co-edited volume called New Findings in Long Wave Research (1988).

In much of his work Mandel ties the ups and downs of the long wave to corresponding movements in the profit rate. His own specific contributions to this discussion fall into two categories.

The first was to show that both the ups and downs in the rate of profit, and hence in the long wave, can be related to the “inner logic of the process of the long-term accumulation and valorization of capital.” (LC, 145)

A long boom raises the organic composition of capital, shrinks the reserve army of labor, and puts pressure on the price of raw materials–all of which undermine profitability and at some point negate the boom itself. (LC, 145-146; The Second Slump, 172; LWCD, 15). Then begins a period of cutbacks and bankruptcies, which only exacerbate the downturn and turn it into a general crisis.

It is at this point that the second critical element of Mandel’s argument emerges: Whereas the long boom and the long downturn are both generated by the internal dynamic of the capitalist system, he argues that:

“[T]here are no economic mechanisms which automatically [produce a long-term expansion . . . . Then everything depends upon the outcome of the struggle between specific social and political forces in a series of key countries throughout the world.” (LC 1992 ed., 232)

The key is the restoration of profitability, although he also suggests that one or more exogenous shocks may be necessary to spark a recovery. On this point he remains open to further debate.

A Passionate and Open Mind

I first met Ernest when we became involved in putting together a book in honor of the marxist economist and activist Bob Langston. I was immediately captured by his intense and passionate concern for the world around him, by his sense of humor, by his ability to argue and disagree, and by his surprising openness to ideas opposed to his own.

Over the years as we corresponded and occasionally met and talked, my affection and respect for him grew. I have tried in these brief remarks to concentrate on a few of his substantial intellectual contributions to international political economy.

But the spirit of Ernest’s life and work is equally important. And here I cannot do better than to quote his own words:

“This is therefore merely an attempt, at once a draft which calls for many corrections and an invitation to the younger generation of Marxists, in Tokyo and Lima, in London and Bombay, and (why not?) in Moscow, New York, Peking and Paris, to catch the ball in flight and to carry to completion by team work what an individual’s efforts can obviously no longer accomplish.

“If this work succeeds in causing such consequences, even in the form of criticisms, the author will have fully achieved his aims, for he has not tried to reformulate or discover eternal truths, but only to show the amazing relevance of living Marxism. It is by collective synthesis of the empirical data of universal science that this aim will be attained, far more than by way of exegesis or apologetics.” (MET, 20)

We are here to salute you Ernest, comrade and friend, and to affirm that there are many hands stretched out across the world to catch the ball, and to then send it back into flight again.

November/December 1995