Against the Current, No. 59, November/December 1995

-

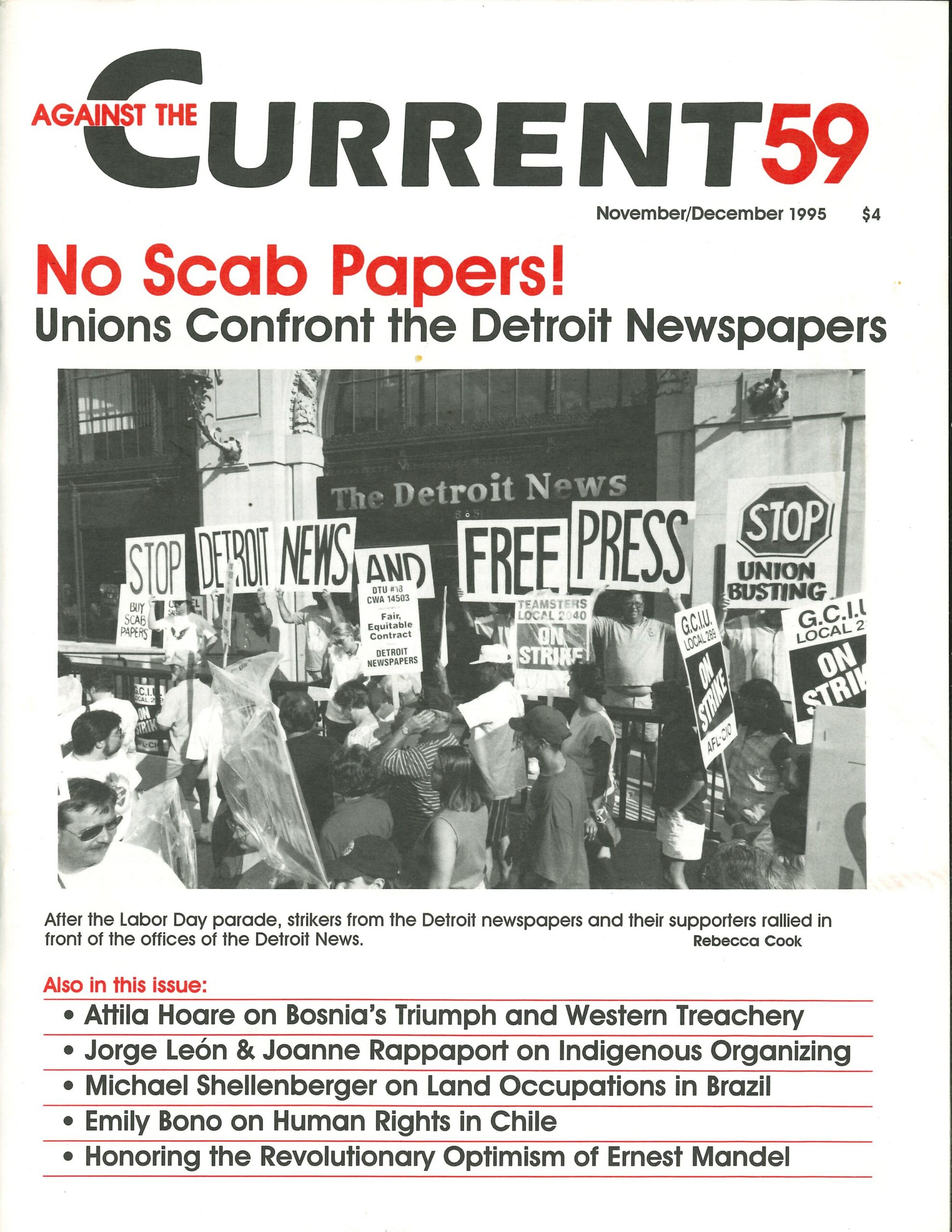

Labor Wars, from Top to Bottom

— The Editors -

The Detroit Newspaper Labor War

— David Finkel -

Potrait of a Strikebreaker

— Roger Horowitz -

Bosnia's Triumph and Western Treachery

— Attila Hoare -

Radical Rhythms: World Music--What in the World Is It?

— Kim Hunter -

Letter to the Editor--and Reply

— Michael Funke; Archie Lieberman -

The Rebel Girl: The Complexities of Inclusion

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Bad Cop! No Donut!

— R.F. Kampfer - A Symposium on Imperialism Today

-

Introduction

— The Editors -

The Shape of Today's Imperialism

— Kim Moody -

Myths of "Humanitarian" Intervention

— Michael Parenti -

Imperialism with a Human Face?

— Paul Le Blanc - Organizing in the Americas

-

Haiti: The Elections and After

— Dianne Feeley -

Chile: The Human Rights Challenge

— Emily Bono -

Land Occupation and Struggle in Brazil

— Michael Shellenberger -

Amazon Peasant Massacred

— Michael Shellenberger -

Forced Labor in Brazil: An interview with James Cavallaro

— Marcelo Irajá de Araújo Hoffman -

Indigenous Organizing in Colombia and Ecuador

— Jorge León and Joanne Rappaport - Reviews

-

Uncracking Crack Coverage

— Janice Peck - In Memoriam

-

Ernest Mandel: A Passionate Optimistic Marxist

— Anwar Shaikh -

Ernest Mandel: Internationalist and Dear Comrade

— Rosario Ibarra de Piedra -

In Tribute to Ernest Mandel

— Andre Gunder Frank -

Ernest Mandel: Revolutionary of the 20th Century

— Manuel Aguilar Mora -

Ernest Mandel: A Revolutionary Heroic Life

— Jacob Moneta -

Hedda Garza, 1929-1995

— Patrick M. Quinn -

William Kunstler, 1919-1995

— Michael Steven Smith

Michael Shellenberger

IT’S 5:30 A.M. as I’m jarred out of sleep by the country music that Gilmar, my 20 year-old Brazilian host, is blasting from the other side of a very thin wall. Early rises to musica sertaneja–country music Brazilian-style–are the most painful aspect of fieldwork in peasant communities, in contrast to Rio de Janeiro where people sleep in late and funk music rules the day.

It is my fourth morning in Nova Fronteira, a peasant community in the southern Brazilian state of Santa Catarina. In Gilmar’s front room I sit near the wood stove and munch on homemade bread and coffee. He passes me a gourd of chimarrão, the hot tea drink ubiquitous in southern Brazil, and my mood begins to improve.

Most here are descendants of Italian and German immigrants, and until 1988 were among Brazil’s five million landless rural workers who scrape out a living working someone else’s land. In that year, Gilmar and his mother Elí, along with other families organized by the Movement of Landless Rural Workers (MST), settled here, joining a land occupation already in progress.

Since its founding in 1985, the MST has forced the federal government to expropriate hundreds of thousands of acres of unproductive farmland for small farmers like Gilmar and Elí. In 1985, the Movement organized over one thousand families (about 7,000 people) to occupy twelve unproductive farms in the region.

By 1988, over half had left the encampment, convinced they would never see the fruits of their sacrifice. Those who stayed were settled by the government in dozens of small communities throughout the region. Nova Fronteira is one of the results of that occupation.

The night before, Elí, Gilmar and I sat watching Sangue do Meu Sangue (“Blood of my blood”), the premiere of a slick new soap-opera about the 19th century slave era in Brazil. The opening episode juxtaposed scenes of opulently dressed white couples waltzing in a luminescent ballroom with images of gunmen shooting down slave families attempting a night-time escape through the forest.

“Slavery still exists,” Elí announced, without turning from the TV. “We were slaves. We had to do everything the boss ordered.”

In 1888, Brazil was the last country in the hemisphere to formally abolish slavery. In 1994 the Catholic Church discovered 25,000 Brazilian slaves in plantations hidden from the public view; hundreds of thousands of others work under forced or semi-forced labor conditions, paying rent or paying off debts to local landlords. Children as young as five years old toil alongside their grandparents, who work until their death.

“One day my husband collapsed in the fields with all the blood rushing to his head. He died when this one was only six,” Elí said, motioning to Gilmar. After her husband’s death, Elí continued to work the land (which was owned by the local mayor) and raise her children.

In the mid-eighties, Gilmar’s older brother Clacir became a militante with the MST, organizing several land takeovers in the region. In 1993 he brought his mother and brother to live in Nova Fronteira. “Our lives have totally turned around,” Gilmar said. Now, instead of a boss they have a community; and to show for their prosperity, a TV, a refrigerator, a laundry machine, and the radio that blasts musica sertaneja.

While the Workers Party (PT) and its leader Lula are the best-known representatives of the Brazilian left, they are just one aspect of a huge nationwide movement of neighborhood activists, women, unions, blacks, students, environmentalists and landless peasants, to name a few.

In 1980, when the PT emerged as the authentic representative of the São Paulo union movement, social movements throughout the country jumped on board, modifying the urban and working class character of the party. At the same time, ever since landless peasants began to organize direct non-violent actions under the banner of the MST, lands occupations have been associated with the Workers Party.

Though the Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB) and the Communist Party of Brazil (PC do B) have been supportive of the MST in various instances, the PT is its most reliable ally. Lula, whose peasant family migrated from the Northeast to São Paulo when he was a young child, seems to identify personally with rural workers and has often come to the defense of the MST when the media and political establishment accuse it of being the vehicle of “violent invaders.”

On the final day of the MST national conference, July 27, Lula showed up in Brasilia at the last minute, calling the peasant organization “Brazil’s most extraordinary popular movement.” For the first time all afternoon everyone was concentrating on the stage. “When you win a piece of land, you don’t stay seated, contented with your little piece–you help other companheiros to occupy and win land too.” The crowd roared in approval.

For the PT, agrarian reform would be an important element in a national plan to stimulate and expand Brazil’s internal economy. In this sense MST settlements represent a model of what a future agrarian reform would look like. “For one-eighth the money Fernando Henrique (Cardoso) spent on his recent trip to Portugal,” Lula contended in his speech, “he could have visited ten [agrarian reform] settlements. He could have seen the solution to the problem of landlessness and poverty in Brazil.”

Like all great peasant movements of the twentieth century, the MST is based on a simple idea: land for those who work it. Though there is a rich tradition of peasant uprisings throughout Brazilian history, never before has there existed a national movement to coordinate isolated land occupations and advocate agrarian reform.

For most small farmers in Brazil life over the years has gotten worse, not better. Inflation and land speculation have increased the value of farmland, pushing over a million rural workers off the land each year since 1960s. Wealthy cattle ranchers, banks and multinational corporations expanded their land holdings through legal and illegal means and, thanks to their influence in the military dictatorship (1964-1985), were rewarded with government credit and subsidies.

Larger than the continental United States, Brazilian territory covers 1.76 billion acres, 780 million of which is titled as farmland. (The rest includes public land, including much of the Amazon, unfit for cultivation.) Yet of those 780 million acres, only 140 million are actually being cultivated or used for cattle ranching. Whereas Brazil exploits just eighteen percent of its potential farmland, the worldwide average is fifty percent.

The extreme underdevelopment of the land began with Brazil’s peculiar colonization. In the mid-19th century, at roughly the same time Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act, which opened up the U.S. western frontier to settler-families, the Brazilian monarchy (1821-1889) closed its agricultural frontier with the Lands Act in order to protect the interests of plantation owners.

As the lands used for export crops became more productive, such as the coffee plantations near São Paulo, entire regions of the Northeast and South were fenced off and kept idle by politically powerful landowners.

In the post-World War II era the mostly urban and academic Brazilian left called for agrarian reform, but they didn’t theorize that rural workers themselves would be the agency of change. The Brazilian Communist Party (PCB), a major political force in the 1950s, argued that national capitalists were the natural enemy of the “feudal” landlords who had impeded Brazil’s evolutionary march toward socialism.

The Communist Party of Brazil (PC do B), founded by dissidents of the PCB in 1962 and strongly influenced by the Chinese revolution, was slightly more combative but like the PCB assumed that the bourgeoisie would lead the movement for agrarian reform.

In the same period, intellectuals and elements within the government proposed that in order to develop the country’s internal economy the State must expropriate large landholdings and settle small farmers. However, it wasn’t until the National Confederation of Brazilian Bishops (CNBB) began the hard work of organizing rural unions and peasant leagues that the movement for land reform began to take hold.

At the Vatican 2 conference of Latin American bishops in 1961, the Church declared that “we have to raise the consciousness of peasants and help them to organize, because there will only be agrarian reform if the workers themselves mobilize.”

Church-inspired land movements, unions and Peasant Leagues posed such a threat to local power in the early sixties that large landowners began to agitate for a military coup, realized with U.S. help in 1964. Thousands of rural activists were tortured, imprisoned and killed in the repression that followed. By 1975, Church activists regrouped and formed the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT), and began again to build a peasant movement.

Even with the largest independent peasant movement in the world, Brazil has never implemented a serious agrarian reform. Ironically it was President Sarney (1985-89), a super-rich landowner from the Northeast and traditional ally of the military dictatorship, who expropriated more land than any other president. Though he was forced to slow down the pace of reform, by the time he left office Sarney had settled 115 thousand families on 10 million acres.

The failure to exploit its massive territory is directly related to Brazil’s profound social inequality, the worst in the world according to the World Bank. The richest ten percent of the population control half the wealth, and the poorest twenty percent are left with just two percent. According to the Brazilian government’s own statistics, eighty percent of the land is controlled by ten percent of all landowners, and the richest one percent control 46.9 percent of the total.

The rupture between the national bourgeoisie and “feudal” landlords foreseen by the Communist parties never occurred. Instead, the landlords were swallowed up by national and multinational consortia that have little incentive to invest in their massive and unproductive landholdings. For instance, the 46 largest properties are owned by industrial, banking and commercial conglomerates that control 48 million acres of land.

Landless peasants desperate for a piece of land have occupied unproductive farms throughout Brazilian history and continue to do so, often autonomously, without any connection to the Landless Workers Movement (MST). “Movement” occupations tend to provide more institutional support to the landless, thanks to the MST’s strong links to the Catholic Church, unions and left-wing political parties.

Moreover, with ten years experience, the MST is often more prepared to provide security for the landless and negotiate a fair settlement. As a rule, the MST only occupies unproductive properties, or latifúndios, and organizers spend months delving into bank records and files collected by each state’s agriculture department, researching the status of farms that are suspected to be abandoned and in debt. Large, idle ranches that have defaulted on loans, especially those to public banks, are the most vulnerable to government expropriation.

Meanwhile, with the help of Church and union activists, the MST recruits as many as 10,000 people from small towns and urban slums to participate in the occupation. Many preparatory meetings are held with the landless to raise consciousness and prepare the logistics for the future occupation. The time and place of the occupation is unknown to all but a handful of the top organizers until the last minute.

Then, around midnight, the families pour onto the land, set up camp, and wait for government action. In the most successful occupations, the government agrarian reform agency INCRA begins to negotiate with the MST to settle the families the next day. In some cases the Military Police (often alongside the rancher’s own gunmen) send in soldiers to destroy the encampment, arresting, beating up and sometimes killing the landless.

Nova Fronteira was founded in 1985, when eleven landless peasant families occupied an abandoned farm whose owner was deeply in debt. For the next three years they lived crammed together in a barn, and though they never suffered police repression they underwent long periods of hunger and illness during the cold southern winters. To earn money to survive, the men worked as day laborers on distant ranches, leaving the women to raise the children and plant gardens.

In 1988, INCRA expropriated the area and began to bring in more families from a nearby MST occupation. The MST families insisted that the entire 4,400 acres be farmed collectively–an unusually radical arrangement that reflected these peasants’ clear political organization and ideology. As is typical in agrarian reform settlements, the younger generation was more willing to break from the individual mode of production of their parents and grandparents.

Those who adjusted stayed; those who didn’t, about 19 families in all, left the area. “Collective production is a slow process,” Valdivina, a 27-year-old father of two, told me. “At first we would say that this was mine or that was yours. Now I can say that this is mine, that all this is mine, even if it’s just a piece of a cow’s tail!” he laughed.

Today, the quality of life on Nova Fronteira is high in comparison to most rural communities, even those associated with the MST. An average meal includes steamed manioc, homemade pasta, salad, meat, beans, rice and juice. Fresh bread, cheese, salami, butter and jelly are always on hand for snacks. Coffee and salt are the only foods not produced by the community. A small jeans factory was set up with the help of a Chilean exile, and little by little the community has invested in tractors, a slaughter-house, automatic milking machines and freezers.

At the weekly community meetings women and men, young and old, participate in discussions and report-backs from various subcommittees. There is a day-care center so that the women of the community can spend the afternoons working outside the home, either in the school, the jeans factory or the fields.

Since winning the land in 1988, Nova Fronteira has remained politically active outside the community, both within the MST and in the left-wing Workers Party (PT). Eight community members work as full-time activists, organizing land occupations and managing MST cooperatives throughout the country. In 1992, Nova Fronteira even succeeded in electing one of its own to the city council on a PT ticket.

Nova Fronteira residents are proud of the social advances they’ve made as a community and distinguish themselves from bichos do mato—-“forest animals,” their pejorative description of families who farm the land individually and isolated from one another. “In the areas of individual production,” one woman told me, “the women don’t even know when planting season begins.”

In contrast to families in poorer, northern Brazil, Nova Fronteira families are small; most parents have one or two children. Over lunch, Valdivina spoke freely with me about birth control, explaining that most use the rhythm method, though some use the pill and others use condoms. The community has hosted a series of discussions of the subject, Valdivina said. Then, with a smile he added, “it’s something families that plant individually don’t talk about. They’re bichos do mato.”

Boy working the land collectively, small producers like those in Nova Fronteira improve their chances of competing against large foreign and national agribusinesses. Families that live on agrarian reform settlements on average earn a monthly salary of $300, three times that of families with the same amount of land yet who plant individually.

At the moment of commercialization, coops are in a better position to bargain for higher prices and, when soundly managed, have more profit to reinvest in the production process. In addition, national and foreign agencies (governmental and non-governmental) make substantial investments in rural coops, though never in individual producers.

Even so, it is rare for any agrarian reform settlement, including those organized by the MST, to achieve the level of collective production reached at Nova Fronteira. Typically, MST cooperatives are more successful at obtaining assistance from the Catholic Church and foreign NGOs than at retaining their members. Those coop members who stay, like the founders of Nova Fronteira, tend to be younger and more willing to experiment with socialized production.

“The cooperative system is complicated, it has a different rhythm,” the president of the COANOL cooperative in Rio Grande do Sul told me. “We always concentrated on winning the land without realizing how hard it would be to maintain it.”

Community leaders I spoke with throughout Brazil all say planning is difficult because most co-op members are illiterate or have only studied up to the sixth grade. Many don’t know basic math and few have experience working as a group. In several instances, families have sold their land after winning it in a MST occupation, convinced they’ll have better luck elsewhere.

For that reason, the MST has prioritized education and increasing production on its settlements, and last year founded an intensive two-year course to train young activists how to manage Movement coops.

Even so, the problem with collective production on MST settlements isn’t so much technical as it is cultural. For families that have farmed the land individually for three or four generations, working collectively can be a difficult, even traumatic experience. For MST families who are thrown together in a land occupation literally overnight, there are no bonds of trust already established to facilitate collective decision-making. Often these families are drawn to the collective only because MST leaders promise future assistance from the government and NGOs.

On MST settlements in the Northeast, creating viable cooperatives is an even greater challenge. As the Catholic Church has discovered, the donation of a rice-processor or a chicken feeder can often cause more harm than good. Often new disputes are created and old resentments accentuated. At one cooperative in southern Maranhão, for example, the membership declined from 32 to 9 families in a few months after disgruntled members accused the president (who was also an MST leader) of stealing from the collective funds.

Staff members of local “entities” (Church agencies and NGOs that work with peasant communities) occasionally criticize the MST for entrusting activists as young as seventeen years old to administer complicated and often violent land occupations. “And then when they run into trouble they don’t come to the entities for help,” according to Maristela Andrade, an anthropologist who has worked with rural communities in Maranhão for the last two decades.

MST militants don’t earn a wage but rather money enough to survive, from $100 to $500 a month. To continue occupying more land throughout Brazil, the MST depends on donations from the communities it established. Yet Eduardo Borges, who worked as a lawyer for a local human rights society, argues that the MST is often insensitive to the symbolic world of small farmers. “When the Movement collects a payment from a rural community to continue its work,” he told me, “it risks reproducing the relationship between landlord and peasant.”

Other peasant communities approached by the MST aren’t necessarily interested in political activism. In Ceará, for instance, I was invited by my MST hosts to visit one of “their” communities located on the beach, the fishing village of Sabiaguaba. I assumed that the MST had won the area in a land occupation.

On arriving, however, I learned that the community had already existed for over fifty years and wasn’t the result of any MST occupation. After a foreign investor tried to take over the fisherfolk’s land to build a tourist resort, a local priest and the Pastoral Land Commission helped them to secure their property.

Though sympathetic to the plight of landless peasants and the work of the Movement, Sabiaguaba is no Nova Fronteira. “We don’t have anything against the MST,” one resident told me, “it’s just that we don’t have the money or the energy to participate in all of their marches and rallies.”

If the traditional image of a Latin American peasant revolutionary is of a macho, mustached strongman, the state of Ceará is home to its symbolic inversion. There, in the violent backlands of northeastern Brazil, the MST is headed by a band of revolutionary women who have organized forty-nine land occupations since 1989.

The movement began that year when 23-year-old Fátima Ribeiro arrived in the capital on her motorcycle and began to organize what would become the second largest movement of landless workers in the Northeast. Without any contacts and spending her nights sleeping in the bus station, Fatima began the difficult work of putting together a team of crack organizers that would soon become feared and despised by the region’s landowning elite.

One of Fátima’s first stops was at the local girls’ convent where 17-year-old Vilanice Oliveira da Silva was studying to become a nun. “She looked like a wild woman!” Vilanice laughed. “She arrived on her motorcycle in the pouring rain, sopping wet and dressed in a mini-skirt. The sisters were scandalized.” A few weeks later Vilanice left the convent and began to work for the Movement.

In Ceará and in other states through Brazil, Vilanice helped organize over fifty land occupations. Her success as an organizer didn’t go unnoticed: Once she had provoked the ire of the landowning class, word went out to make an example of her. During a trip from Ceará to the south, Vilanice was picked up by plain-clothed men and taken to an unidentified locale where she was beaten unconscious.

“The last thing I remember is when they applied the telephone,” she recounted, referring to when the torturer repeatedly slams his cupped hands against the victim’s ears, sometimes causing permanent damage to the eardrums. Vilanice’s ears survived the “telephone,” but she lost a lung due to the beatings. Today it’s difficult for her to walk great distances without losing her breath.

Two years later, after countless therapy sessions and surgeries, Vilanice returned to mobilize land takeovers with the MST. She says that she no longer panics when she comes into contact with the Military Police (PM), who she says were her plainclothes torturers.

Whether it be torture and murder of peasant leaders, or the killing of street children, human rights groups provide ample evidence that PM soldiers are the principal perpetrators of violence against the poor. Violence against MST activists, different from Vilanice’s case, usually takes place when the Military Police moves to expel landless peasants who have organized an occupation. If the government doesn’t move to expropriate the land immediately, the police dispel the landless and make selective arrests.

Sometimes the police do much worse: Over the past decade, 994 people have been killed in land conflicts, the MST reported on September 15. One of the worst massacres occurred August 9 in the state of Rondônia (see box).

Every five years the MST hosts a national congress to articulate its demands to the national government, coordinate strategy and revitalize its grassroots. In July, 5,000 MST delegates from twenty-two of Brazil’s twenty-six states poured into the national capital of Brasilia, demanding stepped-up action by the government to settle landless workers.

Though many of the delegates had traveled seventy-two hours by bus, they could not contain their enthusiasm: For many, it was the first time they had traveled outside of their counties, much less across the country.

On the last day of the conference, with five thousand peasant activists shouting slogans for agrarian reform outside the Presidential Palace, President Cardoso met with the MST leadership. In the meeting Cardoso reaffirmed his campaign pledge to settle 280,000 families by 1998 and raised the level of financing for settled families.

Most important was that Cardoso recognized the legitimacy of the 16,000 families who are currently occupying land throughout the country and promised to provide food for them until the end of the year. Yet nine months into 1995 Cardoso had only settled 14,000 of the 40,000 families he promised to settle in his first year.

Since the mid-1980s, about 700,000 of Brazil’s five million landless peasants have been settled on 15 million acres–about two percent of all idle land in the country. Clearly, building economic power from the grassroots is limited and doesn’t alter the relationship of power between the big landowners, small farmers and the State.

If ten years of the MST as an organization proves anything it is that only a transformation that includes the concerted expropriation of idle latifúndios and support for small farmers, will insure that Brazil’s countryside looks a lot more like Nova Fronteira than Rondônia.

November/December 1995