Against the Current, No. 57, July/August 1995

-

What Is the Main Danger?

— The Editors -

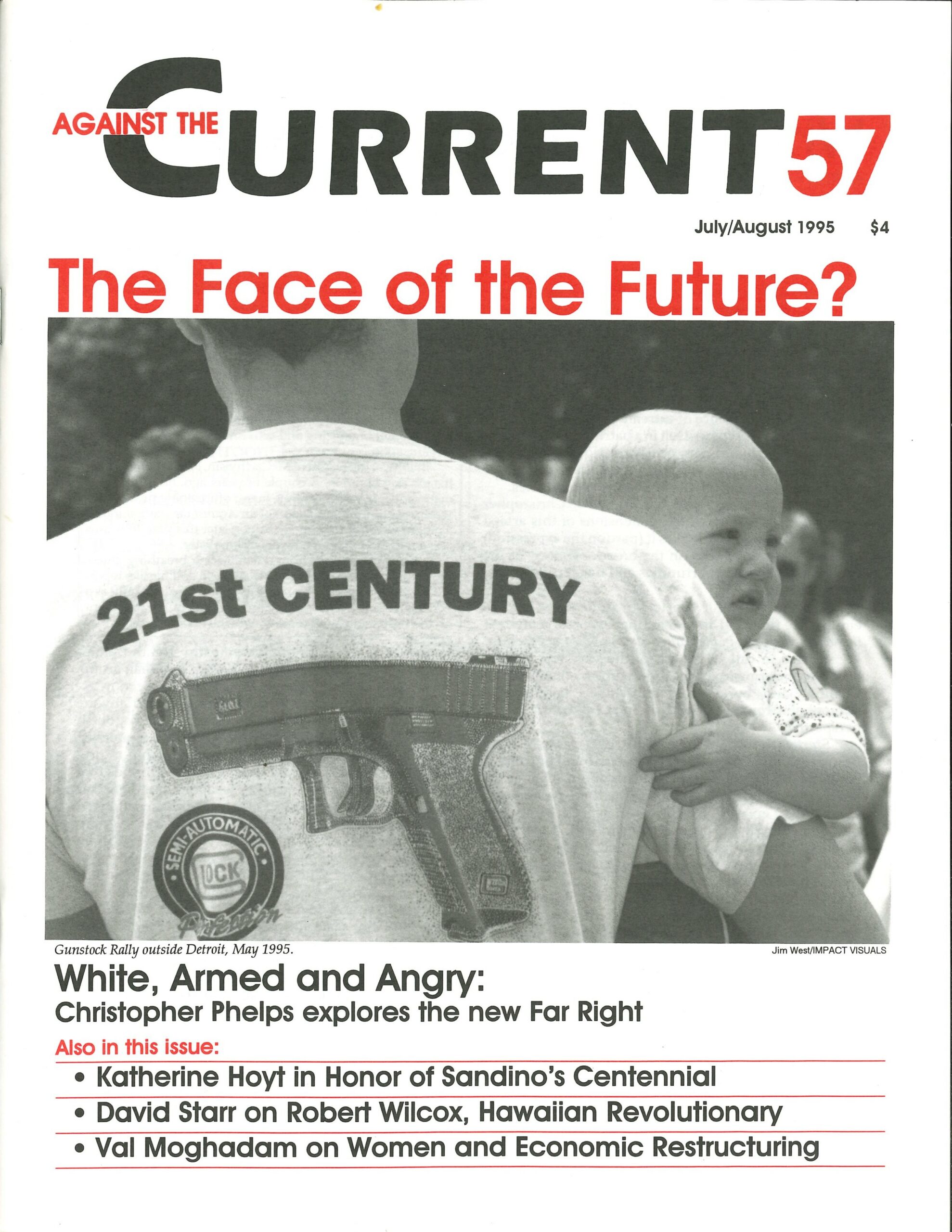

The Explosive Rise of an Armed Far Right

— Christopher Phelps -

Fighting the Far Right

— interview with Jonathan Mozzochi -

Why Is the Far Right Growing?

— Christopher Phelps -

Closing the Courthouse Doors

— Michael Steven Smith -

Robert Wilcox and the Revolution of 1895: Hawaiian Revolutionary Honored

— David Starr -

Gender & Post-Communist Economic Restructuring: How Women Pay the Price

— Val Moghadam -

Race, Class and Sandino's Politics

— Katherine Hoyt -

Finance & Industrial Capital in the Current Crisis

— Mary Malloy -

Open Letter to an Israeli Settler: I Will Not be Your Guard!

— Sergio Yahni - Letters to Against the Current

-

On Bosnia and the Left

— Attila Hoare -

Radical Rhythms: In Honor of Two Musical Titans

— Kim Hunter -

Rebel Girl: Sports Equality, Where Money Talks

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: PROgress and CONgress

— R.F. Kampfer - Reviews

-

Power, Money, Marxist Theory

— Charlie Post -

Shachtman and His Legacy

— David Finkel - Dialogue on American Trotskyism

-

American Trotskyism: A Response

— Frank Lovell -

The Lessons of Working-Class History

— Archie Lieberman - In Memoriam

-

John Evans

— David Finkel

Frank Lovell

ALAN WALD’S “THE End of `American Trotskyism’?” (Part 3, ATC 55) begins with the seemingly unassailable assertion: “There are methodological aspects of Trotskyism that the twenty-five years since the height of `The Sixties’ have shown to be still necessary and valid.”

It may seem little more than a quibble to those who agree with the main point, but it is wrong to leave the impression that “the height” of American Trotskyism was achieved in the 1960s, presumably as a decisive influence in the antiwar movement of that time.

Both numerically and in ideological and organizational influence in the mass movement, “the height” of American Trotskyism was reached in 1938 with the founding of the Socialist Workers Party. The party never again had as many members as at the time of its founding. It subsequently fought many battles and won some important victories, but its ideological influence in the union movement and in the embattled radical movement never exceeded the 1938 high point.

In discussing the charge of “Trotskyist sectarianism” Wald says, “From my experience, liberals and social democrats are quite capable of sectarian behavior equal to that of revolutionary Marxists.” He identifies liberals and social democrats — “Dissent magazine being a good example” — but fails to give an example of “revolutionary Marxists” equally capable of sectarian behavior.

Wald grapples with such questions as revolutionary leadership, party-building and the role of the individual by referring to little-known incidents in SWP history. He says, “The goal of socialist political cadres must be the development of team leadership…,” but that both experience and study teach that “all leaders are contradictory, including Lenin and Trotsky.”

It follows therefore that “one of the most tragic features of the history of U.S. Trotskyism is the inability of individuals, who were once comfortable in an organization and then on the `outs,’ to recognize problems in theory, practice and organization until `one’s own ox is gored.'” These generalizations have little meaning without reference to specific incidents, which are never mentioned in Wald’s selective history.

Revolutionaries Past, Present & Future

Wald gets to the nexus of his grievances against American Trotskyism and the SWP by asking, rhetorically, “whether one should continue the Trotskyist tradition of lining up on historical factional sides, as if someone born in 1940 or 1950 or after was actually present as an engaged participant at the time of the `French Turn’ (1936-37 — ed.) or `Auto Crisis'” (1939 — ed.).

This surely is a gratuitous addition to “Trotskyist tradition,” heretofore unknown. Wald, however, hastens to explain: “This relates to some of the controversies about the so-called `Cannon’ tradition.” He asks:

“Is the proper appreciation of (long-time American Trotskyist leader James P.) Cannon, who certainly represents a good deal of what is most recuperable in U.S. Trotskyist history, to be achieved by retrospectively reinscribing oneself as his right-hand man or woman in all the faction fights he ever waged? Is this the most effective way to combat vulgar and prejudiced anti-Cannonism?”

Wald raises these questions in order to introduce his own “proper appreciation of Cannon.” He explains his motives:

“As a new generation of revolutionary socialist activists emerges, they will have to go back and reconsider these issues in order to develop a theory and perspective on the course of world history that is genuinely produced and not a hand-me-down. If those from the

Trotskyist tradition stand aside from such reconsideration or, even worse, participate only as `seasoned experts,’ it will only heighten their irrelevance. They must, of course, bring their experiences to bear, but also genuinely listen to people from other traditions and keep an open mind about the possibility of genuinely new issues arising.

Here it is necessary to ask the relevant questions that Wald does not address: What social contradictions and political struggles will produce a new generation of socialist activists? Will this new generation resemble and relate to Wald’s generation of 1960s and 1970s socialist activists? What are the “genuinely new issues arising”?

Are these new issues not here now, demanding attention? In case Wald hasn’t noticed, they are the crisis of capitalism and economic exploitation and political repression of the working class and other poor people. These, of course, are not new to students of Marxism — but the social context in which they now appear is new, and the new generation of revolutionists will most likely arise from the developing social consciousness and mass radicalization of the working class.

How will the vanguard educate itself to organize and lead the coming class battles that can emancipate the working class and transform society? These are the questions that radical-minded workers today are beginning to think about, most of whom do not yet consider themselves “revolutionists” in any sense.

Cannon’s Legacy

Wald finally comes to what troubles him most. The concluding paragraph of his essay include two rather lengthy quotations, one from Cannon and another by Morris Stein, “one of Cannon’s most trusted supporters.”

Cannon explained, in his talk on the SWP’s “Theses on the American Revolution” at the party’s 1946 convention, that the SWP “is the sole legitimate heir and continuator of pioneer American Communism…(and) the fundamental core of a professional leadership has been assembled.”

Cannon added that the party’s political task, as he saw it at that time, was “to remain true to its program and banner, to render it more precise with each new development and apply it correctly to the class struggle; and to expand and grow with the growth of the revolutionary mass movement, always aspiring to lead it to victory in the struggle for political power.”

The Stein quotation comes from a talk by him at an SWP gathering during World War II when there were some signs of defection in the party leadership and unfounded hopes of merger with the Shachtman group that had left the SWP on the eve of the war. Stein said that in the field of revolutionary politics Trotskyists “are monopolists (because) the working class, to make the revolution, can do it only through one party and one program.”

This is obviously a very bad attitude, according to Wald, who says, “the Trotskyist tradition has no hope of accomplishing more than the generation of small, sectarian groupuscules unless it breaks radically with the key features of this outlook (as expressed by Cannon and Stein).”

It is hard to reconcile Wald’s demand with the revolutionary perspective of Marxism. Those who aspire to organize and lead a working class revolution must surely state their goal as clearly as possible and explain under all circumstances how they hope to achieve it.

Cannon was called upon to do this when 26 Trotskyists were on trial (18 were convicted) for sedition in the fall of 1941. Under these circumstances, when war was imminent, he expressed the same outlook but in language that the jury could understand and perhaps sympathize with (see Cannon’s pamphlet “Socialism on Trial”).

In the wake of the war and its terrible devastation worldwide, we in the SWP had reason to believe that working class revolutions would break out in several countries, including the United States. At the 1946 convention Cannon was preparing the party for this development. It is true that history developed differently, but no one has yet blamed Cannon for this.

With the stabilization of capitalism in Europe and the thirty-year period of prosperity and class collaboration in the United States, many things changed, including the labor movement and the expression of radicalism. But through it all Cannon never modified his views on the need to work continuously, under all changing circumstances, toward a revolutionary working class party trained to lead the coming struggle for power.

Part of the problem, as Cannon understood it, was that most radicals abandoned the prospect of revolution in the United States anytime in the foreseeable future.

A Test of Perspective

With the decline and disintegration of the radical movement, some who now hope to revive the mass protest actions of the 1960s and `70s are looking for ways to unite the remnants of the radicalism of that period.

They share Wald’s hope that a revived radical movement can be united in a single organization that is more ecumenical than any that ever before existed; and to make clear what kind of organization they hope to create, they are adamant that it must NOT be a Leninist-type party, and certainly (even while “appropriating the best of U.S. Trotskyism”) nothing like the Trotskyist party that Cannon built.

To ensure that arguments over matters of this kind don’t disrupt their work and threaten the future of their unity project, they agree to forgo this discussion except among themselves and with others who might lend a receptive ear without asking too many questions.

I don’t think “the new generation of revolutionary socialist activists” to whom Wald wants to relate will be favorably impressed with his new “theory and perspective on the course of world history,” whatever it turns out to be. Time will tell.

On the CP: A Final Note

Finally, Wald thinks “the Trotskyist criticism of the U.S. Communist or `Stalinist’ movement has been off base” because, he says, “there is evidence that the struggles and impact of the CP-USA out-distanced by far any other organized socialist current.”

In fact, James P. Cannon, who wrote more perceptively and more extensively on the Stalinist phenomenon than anyone else except Trotsky and who said it was the most complex phenomenon of his time, summed it up as follows:

“The degeneration of the Communist Party is not to be explained by the summary conclusion that the leaders were a pack of scoundrels to begin with; although a considerable percentage of them — those who became Stalinists as well as those who became renegades — turned out to be scoundrels of championship caliber; but by the circumstance that they fell victim to a false theory and a false perspective.

“What happened to the Communist Party would happen without fail to any other party, including our own, if it should abandon its struggle for social revolution in this country, as the realistic perspective of our epoch, and degrade itself to the role of sympathizer of revolutions in other countries…(in which case) it becomes a hindrance to the revolutionary workers’ cause in its own country. And its sympathy for other revolutions isn’t worth much either.” (The First Ten Years of American Communism, 38)

Wald tells us that “left-wing scholars in search of a U.S. radical tradition, especially one that is anti-racist and rooted in the working class, return again and again to the Communist tradition.” They find oral histories of the good people who fought the good fight and lived in rewarding comradely ways inside the CP through the many shifts and turns.

This is the way members of the CP generally saw themselves, oblivious to the party’s Stalinist essence and unable to understand the consequences of the political policies they embraced. Many of the scholars Wald mentions tend to ignore or discount the Stalinist cloud that hung over the halcyon days of their own youth. But a view of life in the CP-USA that overlooks the party’s Stalinism at any period in its post-1928 history is a mirage.

Trotskyism always distinguished between the CP’s membership and its corrupt leadership. There is a large body of Trotskyist literature on the subject, including Cannon’s pamphlet “American Stalinism and Anti-Stalinism,” from which Wald might benefit if he will

re-read it with a “partisan but objective” attitude.

ATC 57, July-August 1995