Against the Current, No. 54, January/February 1995

-

The Gingreening of America?

— The Editors -

The Disneyfication of Orlando

— Michael Hoover and Lisa Stokes -

Striking Against Overtime in Flint

— Peter Downs -

A Critical Perspective After Mexico's Election: The Left vs. the Party-State

— Olivia Gall -

A Solidarity Without Borders

— Mike Zielinski -

Anti-Semitism in Argentina

— James Petras -

A Bosnian Activist's View

— David Finkel interviews Nada Selimovic -

How Washington "Aids" Haiti

— Dianne Feeley -

Radical Rhythms: The Pres Blows

— Terry Lindsey -

Problems in History & Theory: The End of "American Trotskyism"? -- Part 2

— Alan Wald -

The Rebel Girl: A Victory, But Only Just

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Post-election Punditry

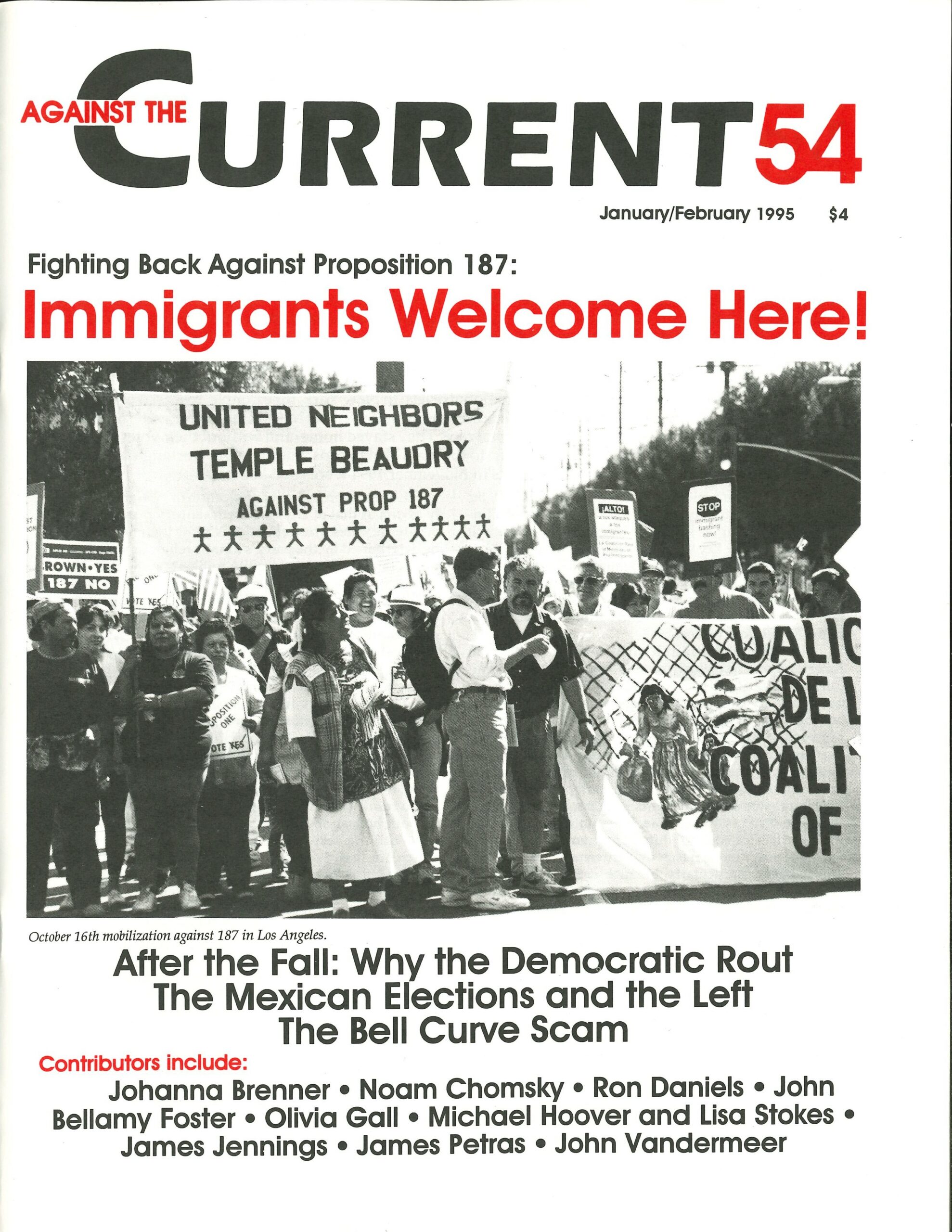

— R.F. Kampfer - California's Propositions

-

Playing by the Rules in California

— Tim Marshall and Rachel Quinn -

Take Their Law and Shove It

— Jim Lauderdale -

Students Against 187

— Angel R. Cervantes -

Assessing the California Single-Payer Fight

— Alan Hanger - Politics After the Fall

-

Earth in the Balance Sheet

— John Bellamy Foster -

Reframing the Welfare "Reform" Debate

— Johanna Brenner -

Black Politics Under Clinton

— Chris Phelps interviews Ron Daniels -

Urban Crisis and Black Politics

— James Jennings -

The Many Crises of Clinton

— A.J. Julius and Harry Brighouse -

Clinton and the Left

— Harry Brighouse - The Bell Curve

-

The Bell Curve: Rekindling A Dead Debate

— John Vandermeer -

The Bell Curve Scam

— Robert McChesney interviews Noam Chomsky - Reviews

-

Theater of the People

— Buzz Alexander - Letters to Against the Current

-

A Look at The Bell Curve's Mainstream Commentators

— Mike O'Neill -

"Arm Bosnia, Abolish NATO"?

— Eric Hamell -

Response: Half Right

— The Editors

Buzz Alexander

Latin American Popular Theatre

By Judith A. Weiss with Leslie Damasceno, Donald Frischmann, Claudia Kaiser-Lenoir, Marina Pianca & Beatriz J. Rizk

The University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1993,

269 pages, hardcover $42.50, paper $22.50.

I HAVE WATCHED Death and his Diseases race through the streets of a dusty Peruvian shantytown, drawing children to a street crossing to witness a play ending in a karate fight between Death and Supervan (Van = vacunacion anual nacional). I watched Death limp off swearing he’ll be back in the spring with Diarrhea, as the children learn lyrics of a vaccination song and loudspeakers tell parents where to bring their children for free immunizations on Saturday.

I have climbed on a barrel to repair the smoking lantern in a large woven cane building in gray, rock-strewn, waterless lightless Huaycan while the taller de teatro from the Center of Popular Communication in Villa El Salvador performed a play about the forming of their own community eleven years before.

I have participated in a week-long workshop on the use of space run by the mime Juan Arcos at the eleventh festival of Peruvian popular theatre in Cusco. In Nicaragua I have listened to Nidia Bustos’ account of her playing the role of a hysterical, ill woman so effectively that the guardia waved on her truck loaded with hollow grenade-filled pineapples.

I have looked out over Nixtayolero’s finca from their open air theatre and learned from Alan Bolt of the company’s projects in agronomy, carpentry, and education, since theater by itself changes nothing.

In Mexico City I have watched CLETA perform a satirical piece in Chapultepec Park’s open theatre, a theatre they were refusing to yield to a government uneasy with their themes. In Argentina I have attended rehearsals directed by members of the Movimiento Solidario de Salud Mental, who do drama therapy with the children of the disappeared. I have participated in theatre of the oppressed workshops with Augusto Boal of Brazil.

In a Chilean poblacion in 1985 I watched a fledgling youth group move and dance to Quilapayun’s “Cantata de Santa Maria de Iquique,” trying, under the silence and fear of the Pinochet years, to give their young audience some of Chile’s history of struggle.

And in downtown Santiago the same year I thought Ictus’ play on disappearances too simple and melodramatic until I heard the woman sobbing in the seat behind me and was told that the lead actor had learned during intermission of another play the year before that his son, her husband, had finally been found, headless, in the hills outside the city.

Latin America Popular Theatre, collectively written by Judith Weiss, Leslie Damaceno, Donald Frischmann, Claudia Kaiser-Lenoir, Marina Pianca, and Beatriz J. Rizk of the Association of New Theatre Workers and Researchers, does those of us with engaged, but eclectic experiences of the New Popular Theatre, and those of us interested in popular theatre in general, the important service of providing a well researched historical/political overview of a theatre movement that came to full life in the 1960s in Latin America.

Part One, “Roots of the Popular Theatre,” takes us through the pre-conquest, conquest, and colonial years, tracing Native American and African dramatic forms and influences and stressing the significance for early Latin American theatre of the medieval European drama current at the time of the conquest.

The authors seek out the subtle infusions of Native American and African culture into Spanish and Portuguese theatrical forms and find considerable popular participation, especially in grand religious pageants. However, on the whole their tale is one of domination by the newcomers, artistic domination by the autos, pastores, and legendary-ritual dramas brought by the conquistadors and missionaries, and domination by the pasos, entremes, loas, coloquios, comedias and college dramas that appeared in the succeeding years.

While they partially accept the notion of syncretism, they reject the idea of a “mutual conquest,” or transculturation, “given the overwhelming historical evidence of the systematic imposition of the conquerors’ values and their socioeconomic systems.” Still, the previous Spanish and Portuguese engagement with Islam and Judaism made them flexible, not erasing the culture they found, but instead imposing on it their own beliefs and worship patterns.

This policy and the “tolerated space” of the eruptive carnival allowed some continuity of native rituals and codes. While the predominant mode of interchange, then, was “substitution rather than fusion,” the authors find it unnecessary “to affirm also that the vanquished have surrendered every inch of ideological territory or that the victory was won without any concessions.”

Hegemony and domination are themes that also dominate Part Two, “The Urban Theatre.” We learn that the elite, literate circles who controlled the central stages from colonial times on sponsored and patronized plays that almost never “spoke with any significant force for the powerless or the marginalized.” Creole artists were suppressed through the dominance of Spanish and Portuguese scripts and touring companies and through direct censorship.

Some popular material from circuses, busker (street theatre) performances, and variety shows reached a general audience through mediating or transitional performance spaces, and some popular characters and themes made their way into commercial plays to help guarantee their popularity.

Yet for the most part the portrayal of the “popular classes and marginal social types” verged on the folkloric and exotic, and comic characters were “usually stereotypes with racist implications” (with rare exceptions like the figure of Cocoliche in Argentina), although such portrayals, the authors argue, did help legitimate popular material. Native people and native language were rarely accorded respect, and too often what respect they received was indianista, an idealizing of the aboriginal past.

The author found examples of popular and political drama in plays adopting native themes in support of the wars for independence, in Cuban and Argentine plays reflecting an attachment to the land, in Jose Marti’s play of sociopolitical indigenismo, Patria y libertad, and in the work produced in anarchist and socialist-worker circles in the twentieth century.

“Out of the Sixties,” Part Three, details the immediate influences and birth of the New Popular Theatre, defines it in all its rich variety, and concludes with vibrant case studies from Cuba, Nicaragua, Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina. The objectives that unite nearly all practitioners of popular theatre are “to expose the mechanisms and dynamics determining general and specific social phenomena and the class character of economic relations, and to demystify the various strategies for manufacturing consensus among different social classes.”

New Popular Theatre groups stress the importance of audience participation and change, and through research and participant observation using oral history, informal conversation, questionnaires, accumulation of lore, and determination of community priorities, they undermine the official stories and create revolutionary theatre and theatre of resistance.

In their general definition, the authors evoke, among other matters, the collective process whereby artists both diversify their expertise and develop their strongest skills; the compatibility of forceful artistic directors and non-hierarchical structures; the fluid relation between grass-roots practitioners and many artists in professional theatres; the importance of national and international festivals, encuentros, and workshops; the fertilization resulting from political exile; the general insistence by popular theatre groups on a broad base rather than narrow political affiliation; the gains collective creation brings to actors, community members, and participating experts; the struggle to ideologize space; and the focus on cultural identity and class struggle.

The most advanced productions avoid folklore, combine legend with modern critical analysis, and present protagonists who “transcend their well-established position of victims.”

The final case study pays tribute to invisible and incidental theater (teatro coyuntural): Chilean women claim that anonymous bodies found in garbage dumps are their own disappeared relatives; youth cover their faces with traditional masks during the Nicaraguan insurrection; the Argentine Mothers and Grandmothers of the Disappeared walk the Plaza de Mayo day after day, and Teatro Abierto, inspired by them, explores the strength of the circle and its own “historical connection to the aboriginal cultures.”

The subject of Latin American Popular Theatre (which excludes the English and French Caribbean but includes in rather token form Latino Theatre in the United States) is grand and complex, rendered especially challenging by the inaccessibility of documentation, not only in the early years, but also to some degree in modern times, when much performance is textless, local, unreported.

The authors are nicely sensitive to the problems of their task, explaining for instance how they might determine a text from the revolutionary years to be unpolitical, whereas intonations and gestures on stage might in fact have rendered it deeply so.

Their task is also difficult, as they announce, because they are attempting in 208 pages to give both a “general overview” and a “detailed chronicle.” And here the book, perhaps inevitably, suffers. The general overview prevails, giving us a plethora of tight, helpful generalizations, of significant categories and distinctions, of accurate lists of historical influences.

The authors have conducted highly competent, careful, responsible, politically thoughtful research, but Latin American Popular Theatre becomes very alive only when we reach the detailed, exciting case studies, which are much more provocative for practitioners and students of popular theater than anything else in the book.

The focus on overview, the collective process of writing, and perhaps a notion of how scholarly work must appear on a page limits too much these committed authors to passionless prose, to a formal clash with the passionate art they tell us of in Part Three. Nevertheless, they have given us an extremely helpful, highly professional introduction to the Latin American popular theatre movement.

ATC 54, January-February 1995