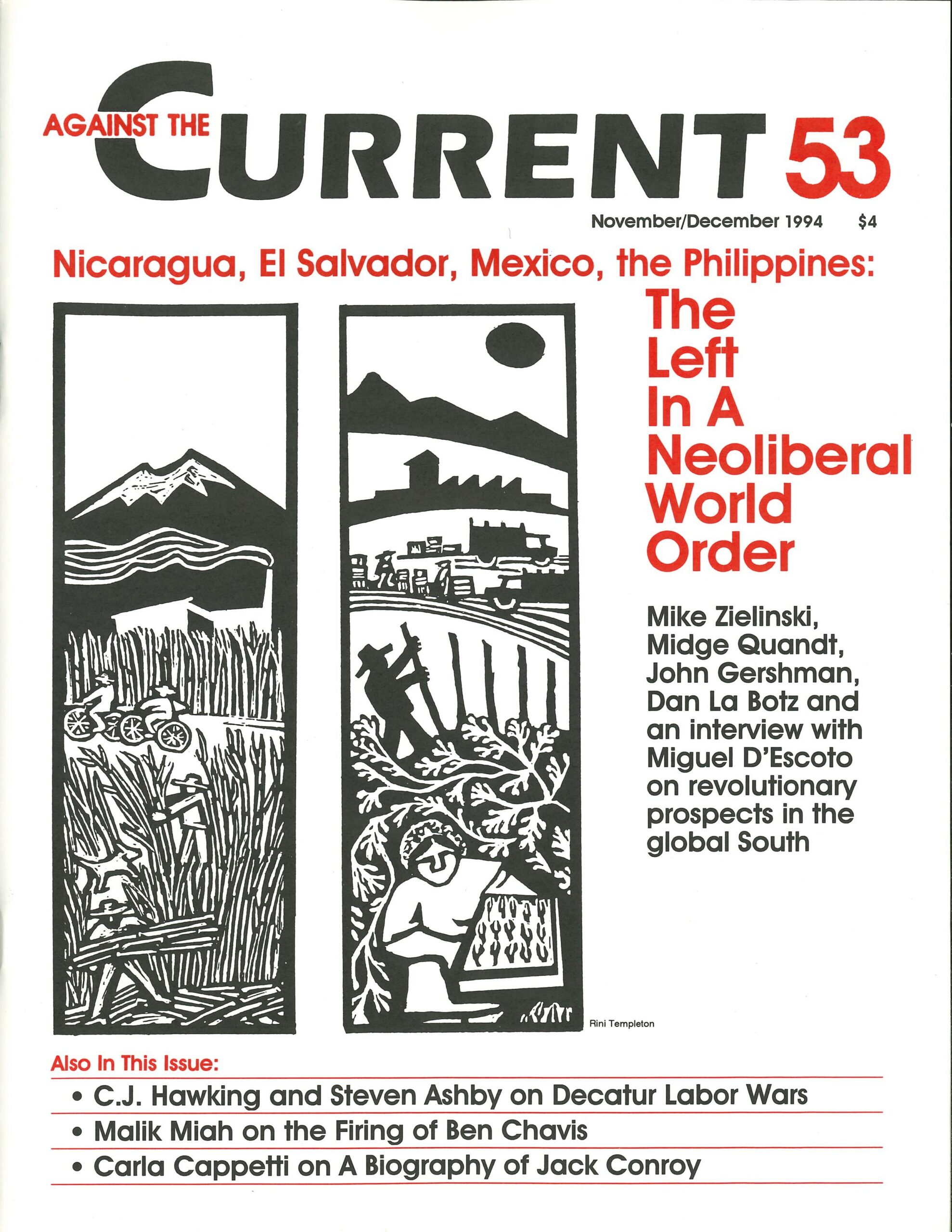

Against the Current, No. 53, November/December 1994

-

Clinton's Best-Laid Plans

— The Editors -

The Firing of Ben Chavis

— Malik Miah -

Decatur Labor Fights On

— C.J. Hawking & Steven Ashby -

Mexico: Zedillo Wins, the Struggle Continues

— Dan La Botz -

Gays & Lesbians in Chile Fight Back

— Emily Bono -

Rebel Girl: Family Planning Without Women??

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Family Values for Beginners

— R.F. Kampfer - The Left Reconstructs

-

The FMLN After El Salvador's Election

— Mike Zielinski -

El Salvador: A Political Scorecard

— Mike Zielinski -

Sandinismo's Tenuous Unity

— Midge Quandt -

Keeping the Dream Alive

— interview with Miguel D'Escoto -

Debates on the Philippine Left

— John Gershman -

The End of American Trotskyism? (Part 1)

— Alan Wald - Reviews

-

Massacre in the Guatemalan Jungle

— Dianne Feeley -

John Beverly's Against Literature

— Tim Brennan -

Jack Conroy, Worker-Writer in America

— Carla Cappetti - Dialogue

-

What Genovese Knew, And When

— Christopher Phelps -

On the PDS: An Exchange

— Eric Canepa -

On the PDS: A Reply

— Ken Todd - In Memoriam

-

Peter Dawidowicz, 1943-1994

— Nancy Holmstrom -

Clarence Davis, Gulf War Resister

— David Finkel -

Earning the Title

— Clarence Davis -

Desert on Detroit River (To Laurie)

— Hasan Newash

interview with Miguel D'Escoto

Fr. Miguel D’Escoto is a Sandinista militant who joined in the years of struggle against Somoza, and served as Nicaragua’s foreign minister during the years of Sandinista government from 1979-1990. He continues to be active in the “Democratic Left” current in the Sandinista party and directs the Nicaraguan Foundation for Integral Community Development (FUNDECI), an organization committed to empowerment of the poor through neighborhood housing, health, youth, reforestation and economic development programs.

D’Escoto was the featured speaker at the July 16 annual Central America dinner sponsored by the Organization in Solidarity with Central America (OSCA) in Detroit. Earlier that day, he was interviewed by Dianne Feeley and David Finkel from the ATC editorial board.

Against The Current: In view of your own history, we want to ask whether you feel that Liberation Theology offers something particularly distinctive in the current crisis of Nicaragua. Or is Liberation Theology simply welded together with Sandinismo?

Miguel D’Escoto: People tend to look at Liberation Theology — all over the world — as if it were responsible for social change. It’s the other way around!

People more and more, at least in Latin America, were discovering that things are the way they are not because of any predestination or divine will, but because of human greed and the way we shape society — and that it was imperative for us as Christians (this being the Christian reflection) to get involved, and to move from the fatalistic conscious to a more liberated one.

The so-called Liberation Theologians reflected on this practice that emerged in Latin America, and they agreed with what people were saying: that if we are Christians we must fight for brotherhood and sisterhood.

First, then, came a revolutionary practice — and you find the Church totally incapable of dealing with it, not understanding the reality or, I would say, the Gospel either. Not only was the Church uninvolved, it was actually preaching sin — because it preached resignation without any qualification.

Now some kind of resignation can be virtuous, when you resign yourself in the face of the inevitable, for example if I’m told that I’m going to die of a deadly incurable illness. But resignation is sinful when it is tantamount to collaboration with an exploitative human system.

Just by not protesting we support the system. Yet for centuries the Church said, “you are suffering injustices here so you will be rewarded hereafter.” I’m not so sure! Rather, you will be rewarded to the extent you fight for justice here.

They almost make it sound sinful to do away with poverty because our Lord said, the poor you shall always have with you. But this lack of acceptance of Liberation Theology is because the Church has been wedded to a different theology, a domesticating theology, which may be good for chickens but not for human beings.

ATC: In the current situation of neoliberal policies and the determination of the right wing to reverse the gains of the revolution, is there some particular aspect of Liberation Theology that is helpful in building resistance?

MD’E: At this particular time, in Nicaragua and also other countries that were embarked on a revolutionary agenda and now find the situation reversing, you have the big temptation to review your ideals, to see if you should keep them.

There’s the temptation maybe to say, in the name of realism, in this new world without the Soviet Union and after the great collapse of the Eastern European governments, we must trim our dreams. And some are saying that in Nicaragua also, and they reason that this is what realism and pragmatism oblige us to do.

But there are those, including myself, who say we must keep the dream. We must not give up on the possibility of justice as the only real guarantee of peace — without it we might have the appearance of peace while the time bomb continues ticking.

For people like myself in Nicaragua, it’s because of our faith commitment that we aren’t giving up the dream. For revolution in our environment is also a moral imperative, not necessarily because we want to be on the “winning side” but even if the harvesting will not come till the next generation.

We believe that to be Christian means to be actively involved in the coming of the Kingdom — which means, for us, a society where we treat people as brothers and sisters. This is theology, yes, but more than that.

ATC: Coming out of the recent Sandinista congress are some Theses on the Countryside. Do these represent possibly the beginning of an alternative economic model to the neoliberal offensive?

MD’E: Yes, they talk about that; but I believe that this world is altogether too interconnected for the possibility of a truly profound revolution in any one country being able to survive in a shark-infested sea.

Right now it is very difficult for us to do anything good for the people in any country, because the most powerful nation in the world, economically and politically, is totally committed to fighting against such change.

You don’t necessarily have to have a madman like Reagan — who I said should have been committed, not elected — the most important thing to understand is that the biggest enemy of democracy in the world is the government in Washington, DC. And Nicaragua, which is in a truly basket-case condition, which was already very poor after a half-century of U.S.-imposed dictatorship, was the fundamental target of the United States for a decade!

In a country like Nicaragua I think it’s important to keep trying, keeping the dream alive, knowing you can’t make too much progress but waiting for the tide to change, for new times.

Presently it’s getting worse and worse. You talked about neoliberalism. Neoliberalism is going straight for the destruction of the nation-state and the possibility of democracy, because the vitally important decisions that affect the lives of the citizens of any one of our countries are shifted to the multinational corporations, way beyond the reach of the citizens of any or all countries.

So you might be successful in bringing huge numbers of people to demonstrate at the presidential palace — but the president will say, “I have no power, it’s beyond me!”

ATC: The other side of neoliberalism is ideological: to convert people so that they accept privatization, atomization, no community, no solidarity. So keeping the dream alive, as you put it — what methods do you find effective for doing that?

MD’E: I think the question you are asking now is the key question I’ve been asking myself over the years. How to keep the dream alive — and how do I keep my commitment alive and help my companeros and remain faithful to our commitments, our dream?

I don’t know — I know what I do myself to stay faithful, but I have seen so many change after five, ten, even twenty years of struggle. People I had never expected to change tend to rationalize themselves into diluting the dream.

I’m talking here not so much about politics, but about mystique, about spirit. Most religious leaders<197>the professionals of religion — are like fire fighters, who come with a huge hose to wet down the spirit, not to spread the fire that our Lord said he came to spread.

We have two big problems, the most powerful institutions in the world — the United States and the Vatican. It’s a sad thing to say, but as you invited me to think and reflect, that is what I have to say.

Our dream will be realized only when we are truly committed to the point of being willing to risk our lives. I think Martin Luther King said, if we don’t have something to be willing to die for then we don’t have a life worth living.

ATC: If Nicaragua needs to await a better time, what about the inspiration of Brazil and the Workers Party (PT) there? What impact would a PT election victory have for you?

MD’E: I wasn’t saying Nicaragua should quit; we should continue to struggle, knowing that we are swimming against the current — that’s the name of your journal, isn’t it?

Of course Lula’s (PT leader and presidential candidate in Brazil — ed.) victory would be extremely important for people throughout the world. One must hope that he doesn’t get killed or that they don’t come up with another Collor de Mello at the last minute.

But what is going to happen after he is elected? Even though Brazil is huge and somewhat rich compared to other countries in Latin America, the situation is difficult even for the big ones. The environment — the capitalist environment — is lethal.

They’ve tried very hard to present what happened in Eastern Europe as a defeat of socialism and a victory of capitalism. It is neither, for capitalism has done nothing to show it can fill the gap. Capitalism can’t come up with anything other than neoliberalism, the revival of the most cruel Manchesterian system (the unbridled exploitation of the early nineteenth century factories — ed.).

On the other hand socialism has not proved viable, but we can’t stop trying. The overwhelming majority of the planet’s inhabitants would go along with that — only the wealthy think that capitalism is viable, because it’s a system with the dice loaded in their favor. What capitalism is doing is increasing the destructive power of the time bomb of injustice.

ATC: Are there some experiences in Nicaragua — thinking again about the Theses on the Countryside — some local and peasant cooperative efforts that give hope to keep the dream alive?

MD’E: Yes, there are, and not only in the countryside but all over. But what is absolutely necessary in Nicaragua is to start from zero again.

The initial Sandinista idea, right after the overthrow of Somoza, was to have a big national coalition. Remember, the first government coalition included Dona Violeta Chamorro and Alfonso Robelo. We wanted very much to move forward united, to explain to the rich that they had to be open to the possibility of tradeoffs to achieve justice.

But we could never get involved in this kind of dialogue within the Nicaraguan family. I came up (to the U.S.) once with Arturo Cruz, who had just become a member of the government. We were at a reception in the State Department. Larry Pezzullo, who was then the U.S. ambassador to Nicaragua, spoke in a loud voice, to make sure everyone heard – “that man over there is Arturo Cruz, the Abraham Lincoln of Nicaragua, the man who can save the boat.”

I was looking at Arturo, and I could see in his face the transforming effect of that kind of flattery.

[Arturo Cruz subsequently became a contra leader. Lawrence Pezzullo most recently distinguished himself as a special envoy to Haiti, where he cultivated sympathetic ties to the military rulers terrorizing that country — ed.]

But now that U.S. leaders are involved in so many other things, not so obsessed with Nicaragua — in fact, they would like it to disappear because it’s a constant memorial to their own criminality — now we are trying again to put together a broad national coalition.

You now find people from the right approaching the Frente and saying, you can bring us together. Before, it was the U.S. embassy that brought them together for what they called “the restoration of democracy.” Since “restoration” means “bringing back again,” that must have meant bringing back somocismo.

ATC: What about the rise of the mayor of Managua, Arnoldo Aleman, who seems to represent the new leadership for the far right? He is developing a reputation for “getting things done.”

MD’E: Aleman can get funding from AID (the U.S. Agency for International Development) for street repairs and the like. There is no doubt that Aleman is the U.S. candidate, not in quite the same way as Ms. Chamorro in 1990 was the candidate of all the people in Washington, but he’s the candidate for those who have a candidate, like Jesse Helms and others of the extreme right.

He has money, and with money you can pave streets. What you will have if he comes to power is the return of somocismo; he was a Somoza “Liberal.”

ATC: Finally, on the Helms-Gonzalez amendment, which has a July 31 cutoff of aid to Nicaragua: Does this create a crisis in the Chamorro government or will the date pass and nothing much happen? [This amendment demands the return of property to former Nicaraguans, somocistas whose real or alleged property was confiscated, who have subsequently become U.S. citizens. It has become law. — ed.]

MD’E: These people fled because they were in cahoots with Somoza. Becoming U.S. citizens is the best way to try to recover property that was never theirs to begin with.

At the State Department, they told me months ago that 100 Nicaraguans a month were becoming U.S. citizens for just this purpose. We told the State Department that this is incredible, that there is no basis for these claims under the law. They told us: Yes, we know, but our congressmen don’t necessarily know much about law.

So now the Nicaraguan government is supposed to be looking at a list of maybe twenty-two or twenty-seven people, feeling that if they do something about these cases — twenty-two whose former homes are now government property, and another five where people are living — they’ve been led to believe that resolving these cases will put an end to this U.S. intervention.

ATC: We wouldn’t bet on that (laughter).

[At the end of July, the Clinton administration granted Nicaragua an exemption against the law for which it was specifically written! It was apparently arranged through the efforts of the U.S. ambassador to Nicaragua and against the wishes of the far right. — ed.]

ATC 53, November-December 1994