Against the Current, No. 47, November/December 1993

-

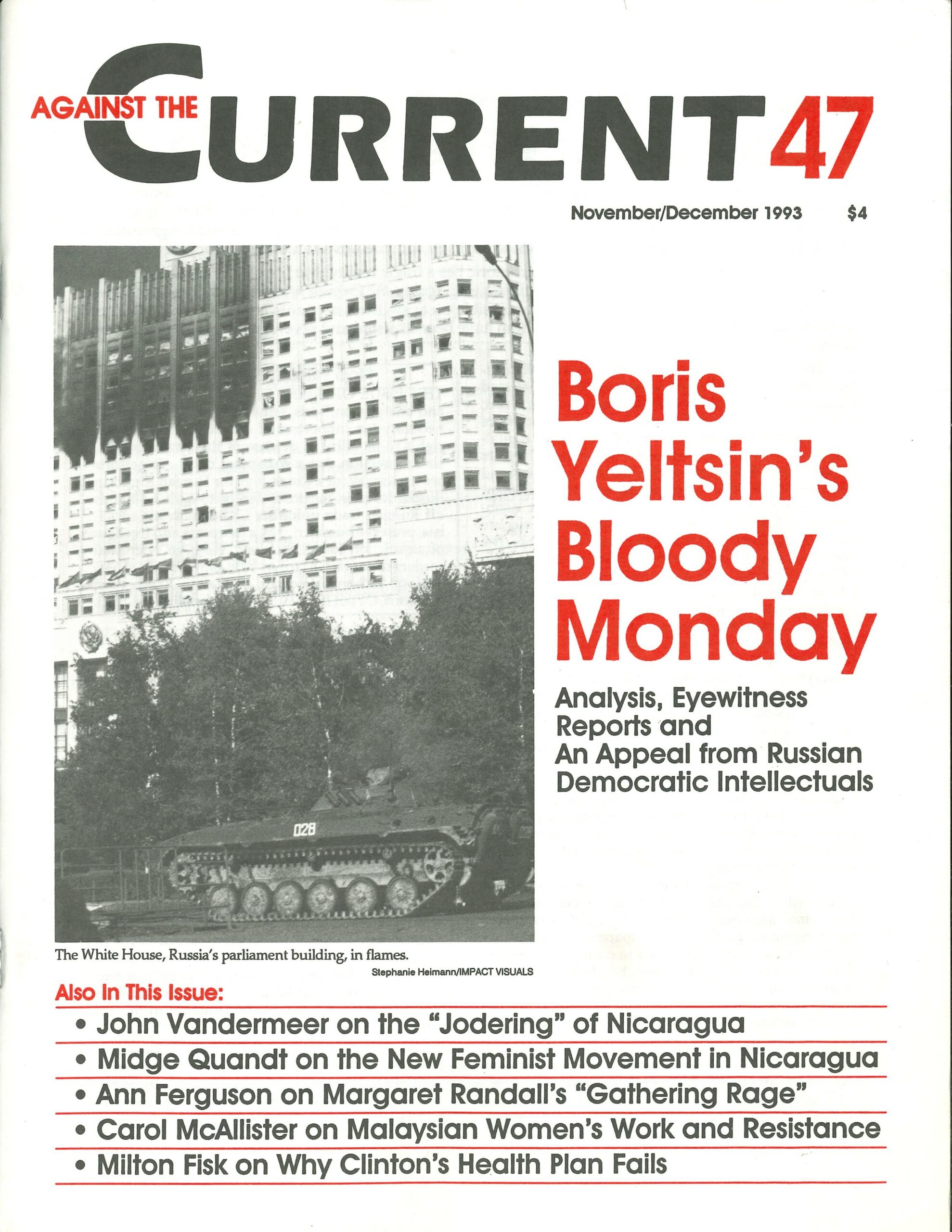

Moscow: The Fire This Time

— The Editors -

Israel-PLO Accords: Peace or Apartheid?

— David Finkel -

Clinton's Failing Health Plan

— Milton Fisk - Statement from Russian Democratic Intellectuals

-

"Order Reigns in Moscow"

— Justin Schwartz -

Bloody Moscow, October 1993

— Susan Weissman -

Whose Coup? Whose Democracy?

— David Finkel -

Russia: A Bureaucracy That Can't Die

— Kit Adam Wainer -

The Jogering of Nicaragua

— John Vandermeer -

Nicaraguan Feminists: "No Political Daddy Needed"

— Midge Quandt -

Gendering Socialism

— Ann Ferguson -

Background: Malaysia in Brief

— Carol McAllister -

Malaysia: Women's Work & Resistance

— Carol McAllister -

The Rebel Girl: Mirror, Mirror on the Wall....

— Catherine Sameh - Reviews

-

Jazz Vs. New York's Caberet Laws

— Michael Steven Smith -

Random Shots: Pixilated Political Paradoxes

— R.F. Kampfer -

U.S. Cuba: Defeating the Blockade

— John Daniel -

Europe & Freedom: A Response

— Loren Goldner -

A Popular Regime, Not Stalinism

— Marc Viglielmo -

Samuel Farber Responds

— Samuel Farber

Midge Quandt

FOR THREE DAYS in January 1992, some 800 women met in Managua to explore gender issues in a space free of male control. After a decade of subordinating women’s needs to the goals of the revolution and the prosecution of the contra war, the Nicaraguan women’s movement was declaring its independence from the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN). “We want a movement where women choose their leaders and their lines of work. We don’t need a bunch of men telling us what to do,” declared one conference participant.

Since the FSLN’s electoral defeat in 1990, the feminist movement has emerged from the tutelage of the party. Conditions which bred a hierarchical mode of organizing—-the capture of state power and the contra war—-were replaced by ones which favored the growth of civil society and its autonomous social movements. Without the apparatus of the state, the FSLN could no longer control or co-opt them, the women’s movement included. As a result, feminists have been able to establish their organizational autonomy and, with varying degrees of success, their ideological independence.

Taking advantage of the new openness, progressive women have formed a multitude of new groups, including collectives, networks and women’s centers. These exist side by side with older groups like the Sandinista women’s association, AMNLAE, and the women’s sections of the trade unions. Whereas AMNLAE addresses the needs of poor women and the sections concern themselves with union members, the new groups give greater weight to the gender oppression that cuts across class lines.

The resulting diversity, while creating certain tensions, has invigorated the movement as a whole. Alba Palacios of the rural workers’ union spoke for many when she addressed an International Women’s Day gathering this year: “We advocate a women’s movement that is broad and united, where all of us have space …. one that respects the organizational forms of each group and their diverse realities.”

Some parts of the movement have been less willing to break with the FSLN than others. The organization most associated with it is AMNLAE, which is formally autonomous, but whose verticalist leadership consists of long-time party stalwarts who take their cues from the FSLN, not from their own base. Like the party and the traditional left, the leadership holds that women are primarily oppressed not by patriarchy, but by the class system, and its work reflects this mind-set. (There is reportedly more ideological diversity at the grassroots and more of a willingness to work with women who are not party militants.) Freed from the control of the FSLN and from the constraints of wartime, AMNLAE is able to focus on female unemployment, violence against women and health services, but its work too often fails to challenge sexism.

The women’s sections of the unions have been more independent of the party than AMNLAE but, in the eyes of many activitists, their inclusion in male-dominated organizations places limits on their feminism. In the process of defining a political agenda, sexual politics often takes a backseat to the politics of class. For example, the sections acknowledge the influence of machismo on women’s subordination but often put the blame on capitalist society. “Men as such aren’t the problem,” says union leader Sandra Ramos. “It’s more the class system and the government.”

The programs of the women’s sections clearly bear the stamp of a mixed organization. Union women do some consciousness-raising work in the area of family planning and domestic violence, but they tread lightly on the issue of male domination. Moreover, many of the programs, which offer services for women rather than addressing the causes of their oppression, end up taking a band-aid approach. Finally, much of women’s energies go into activities that include men, such as work around the property issue and factory closings.

Independent feminists have emerged as a strong force within the movement. Most fault the FSLN for gender-blindness, homophobia and authoritarianism. “After the elections,” notes Ana Criquillon, “much of the movement said, ‘We don’t need a political daddy looking after us. We want to be on our own.'”

Conferences, Campaigns, Networks

Like other feminists in Latin America, Nicaragua’s independent feminists take women’s class oppression seriously. This was evident at the January 1992 conference that they organized, where the workshop on the economy drew the most participants. But they do not privilege a class analysis or a concomitant service approach, which typically sidesteps the issue of male power (and confrontation with the male left) “Unlike AMNLAE and the union women, our collective is not a service center,” says Maria Teresa Blandon whose group, La Malinche, took the lead in organizing the conference. “We won’t set up clinics and nurseries. We target patriarchy more than the government Above all we don’t ask anyone’s permission to be feminists.”

The basic premise of the conference was organizational and ideological autonomy. Within that framework, it addressed the issues of violence, health, sexuality, economics, education and the environment A series of networks that emerged from the conference are still active. “The work we’ve done in the last year has allowed us to coordinate our efforts and define future directions,” said Silvia Carrasco, a member of the network against violence.

In October and November of 1992, forty groups came together in an ambitious campain called “Breaking the Silence No to Sexual Violence,” which involved workshops, magazines, radio and TV. Some feminists, however, believe that the networks are too loosely organized and there is insufficient coordination. What is lacking, in the view of La Malinche’s Olga Maria Espinoza, “is an organization to facilitate joint actions in response to state policies.”

La Malinche, in August 1992, pulled together what it hopes may be the forerunner of such an organization—-the National Feminist Committee (CNF). Made up of thirty different groups, the CNF has set ambitious goals. It is developing seven themes that reflect the triple emphasis on gender, class and ethnicity. And it has also organized a Nicaraguan feminist conference for October of ’93 and a Latin American conference for November.

The larger aims of the CNF involve the political arena. According to journalist Sophia Montenegro, “We want to put forward a global proposal for the women’s movement that would fit the national project of the left” as it contests the conservative government of Violetta Chamorro. This may or may not mean an alliance with the FSLN in the elections of 1996. What it does involve is developing a systematic understanding of capitalist patriarchy. “We’re tired of activism,” says Montenegro. “It masks a fear of facing the real issues. Women need time to think.”

The theory work currently being carried out in its participatory-style seminars, says Maria Teresa Blandon, is not “the intellectual recreation” of bourgeois feminists that other women accuse it of being. Like many U.S. feminists, Nicaragua’s independent feminists believe that understanding the causes of women’s subordination, far from being a luxury, is critical to the struggle for liberation.

It is expected that the seminars and the October conference will result in a coherent political strategy for the public arena. “We need to be clear about our program,” insists Montenegro. “No one believes you if you just complain, because everyone in Nicaragua is complaining, and no one has an alternative. If we have solid arguments, people will pay attention.”

The Feminist Collectives

La Malinche, which put together the CNF is one of a diverse set of groups within it. The collective is determined “to take feminism out of clandestlnity,” and it makes a point of distinuishing it from the gender perspective of more traditional left women, a perspective that slights power relations between the sexes. La Malinche organized the CNF with the purpose of developing an autonomous current within the women’s movement. (Not all independent feminist groups belong to, or agree with, the CNF.) And for some time it has advocated a common program to give the movement clout and to counter its heretofore defensive posture.

Another aspect of the collective’s work is discussion and writing, A topic that appears frequently in the Montenegro-edited magazine, Gente, is sexuality. Many of the articles reflect the group’s thinking on the right to sexual pleasure—-too often denied women by machismo-—and sexual preference. La Malinche believes that the lesbian option is an important one for women, but that does not mean that it is more radical or feminist. In its view, “compulsory lesbianism” would only divide the movement. More desirable is the kind of fluidity that allows women to be heterosexual, lesbian or bisexual at different times in their lives.

Lesbian and bisexual women make up the collective, Nosotras. Until recently the outcasts of the movement, they have now gained acceptance. According to Hazel Fonseca, the CNF is the most receptive place for them because it is willing to fight for the right to sexual choice as well as sexual pleasure and, unlike the still homophobic AMNLAE, it is not under the Sandinista party’s thumb.

The issue of sexuality is central to the collective. “Women have the right to demand sexual pleasure,” says Fonseca. “Men and society have ripped away our eroticism and left us with only the emotional, sentimental elements.” In its workshops, Nosotras emphasizes that procreation, intercourse, and a genital focus are not all there is to sexuality, noting that for women the whole body is an erogenous zone. It shies away, however, from any definition of a feminine or politically correct sexuality. “We need to explore and experiment,” maintains Fonseca. “It’s time for it.”

Another feature of the collective is its rejection of the identity politics that fragments social movements and progressive efforts in the United States. The politics of identity brings with it the belief that a shared identity, be it race, nationality, gender or sexual preference, should be the focus of political work.

The members of Nosotras, by contrast, neither privilege a lesbian identity nor advocate lesbian separatism. “It’s not the person you sleep with that defines the self,” declares Fonseca. “It’s how you think about yourself.” And they think of themselves as women first, lesbians second. The collective also supports the bisexuals in the group. (“We won’t police each other, feminists shouldn’t have just one way of thinking.”) In addition, it makes common cause with gay men around homophobia and AIDS. Finally, there is the class element. Nosotras women identify with the popular classes in their struggle to maintain the gains of the revolution. Thus a social justice agenda forges a bond that works against the dispersion of political energies.

March 8 House, a women’s center serving forty-three Managua neighborhoods, is a very different group than Nosotras. Also a collective, it runs a gynecological clinic, offers medical and legal help to abused women, and gives workshops on self-help and domestic violence. Like other groups in the CNF, the ideological focus of its work is patriarchal oppression.

“We tell women that violence is a problem men have because of the way they were brought up,” says Luz Marina Torres. “It’s part of women’s subordination to blame ourselves when it’s not our fault” She contrasts this consciousness-raising approach with that of AMNLAE, which blames most of the violence on poverty, and whose work with battered women zeroes in on immediate solutions. The problem, as Tortes points out, is that the cycle of abuse continues; only a change in the power relations between the sexes will stop it.

On the matter of sexual pleasure, March 8 House takes issue with the traditional left, which considers it a luxury for women who have trouble feeding their children. “Daily life is hard,” admits one worker at the center, “but for poor women, dreams, hopes, and pleasure count too.” Party-identified women, argues the collective, do not want to focus on sexuality for fear of scrutinizing their own lives, questioning patriarchal definitions of “normal” sex, and challenging male power in bed.

According to Torres, AMNLAE justifies its attacks on independent feminists by saying, “All they are interested in is sex, this weird, exotic stuff.” Though this reflects AMNLAE’s ideological bias, it is also a way of sidestepping a deeper matter. Its fundamental objection to independent feminism is that it contests the power structure of a male-dominated society and the FSLN’s complicity in it. March 8 House confronts this issue head-on.

Educating for a Non-Sexist Future

Another group that focuses its work on patriarchy and the unequal power relationships that result between men and women, adults and children, heterosexuals and homosexuals, is Puntos de Encuentro (Common Ground). it is a non-profit, alternative media and education center that works toward building a non-sex1st, non-heterosexist and non-adultist society. Puntos engages in a variety of activities that deal in practical terms with gender, generational, and sexual identity, domestic violence, and sexuality. One important aspect of its work is training. It offers courses on sex and AIDS, violence against women, and masculine identity. In addition, Common Ground is also concerned with research. It is doing a study of indienous women and has produced a pamphlet on sexism in the schools.

Communication and media work are central to the organization’s mission. As psychologist Vilma Castillo points out, it is “committed to a notion of radical social change based on the dissemination of new values and new ideas for human relationships.” Puntos encourages television and radio to cover its issues and has its own radio program for youth (on Mother’s Day the topic was mothers and whores).

The women’s magazine, La Boletina, has as a goal the sharing of information about alternative ways to construct daily life. Also important is the magazine’s role in fostering communication between different types of women and providing them with a sense of belonging to a movement. But La Boletina does not push one political line (as the pamphlet on sex does not speak of one feminine or feminist sexuality). Conscious of the diversity of women’s groups in Nicaragua and the differing degrees of consensus among them, its strategy is to be as inclusive as possible.

The spirit of inclusiveness is part of the larger political strategy of Puntos de Encuentro, as it situates itself within the women’s movement. Though willing to work with the CNF, it is not a part of it. “We are as ambitious as they are in our desire to reach more women, play a role in politics, and influence public policy.” says Amy Bank. “Where we differ is on the best way to do this.”

Whereas the CNF insists on autonomous organizing and aims for a unified political platform, Puntos sees things differently, opting for a broad and flexible movement. “Though in theory the CNF is open to all,” notes Ana Criquillon, “in practice it excludes women who don’t call themselves feminists, work in mixed groups like unions, and don’t break with the male leadership.” In addition, Criquillon believes that the insistence on a unified body of theory and a single political platform is misplaced. This undermines attempts at unity at a time in our history when there has never been more division,” she maintains. In the belief that unity in diversity is possible, as well as desirable, Puntos de Encuentro hopes that the different branches of the movement will come together by working on the upcoming elections.

Independent feminist groups have much in common besides autonomy and a strong position on sexism. All reject a rigid or politically correct definition of “woman” or women’s sexuality. This stance is not unrelated to their refusal to engage in the kind of identity politics that characterizes much of U.S. feminist and progressive work. Espousing fluidity rather than a fixed identity is part of the inclusiveness of the movement Because of a shared commitment to the revolution, to social justice and to the popular classes, feminists have multiple allegiances and are not fixated on a female or lesbian identity. Thus they avoid the fragmentation so typical of social movements in North America. This strengthens their hand as they move to influence not only the politics of the left, but the politics of a country that still bears the stamp of a liberatory revolution.

November-December 1993, ATC 47