Against the Current, No. 29, November/December 1990

-

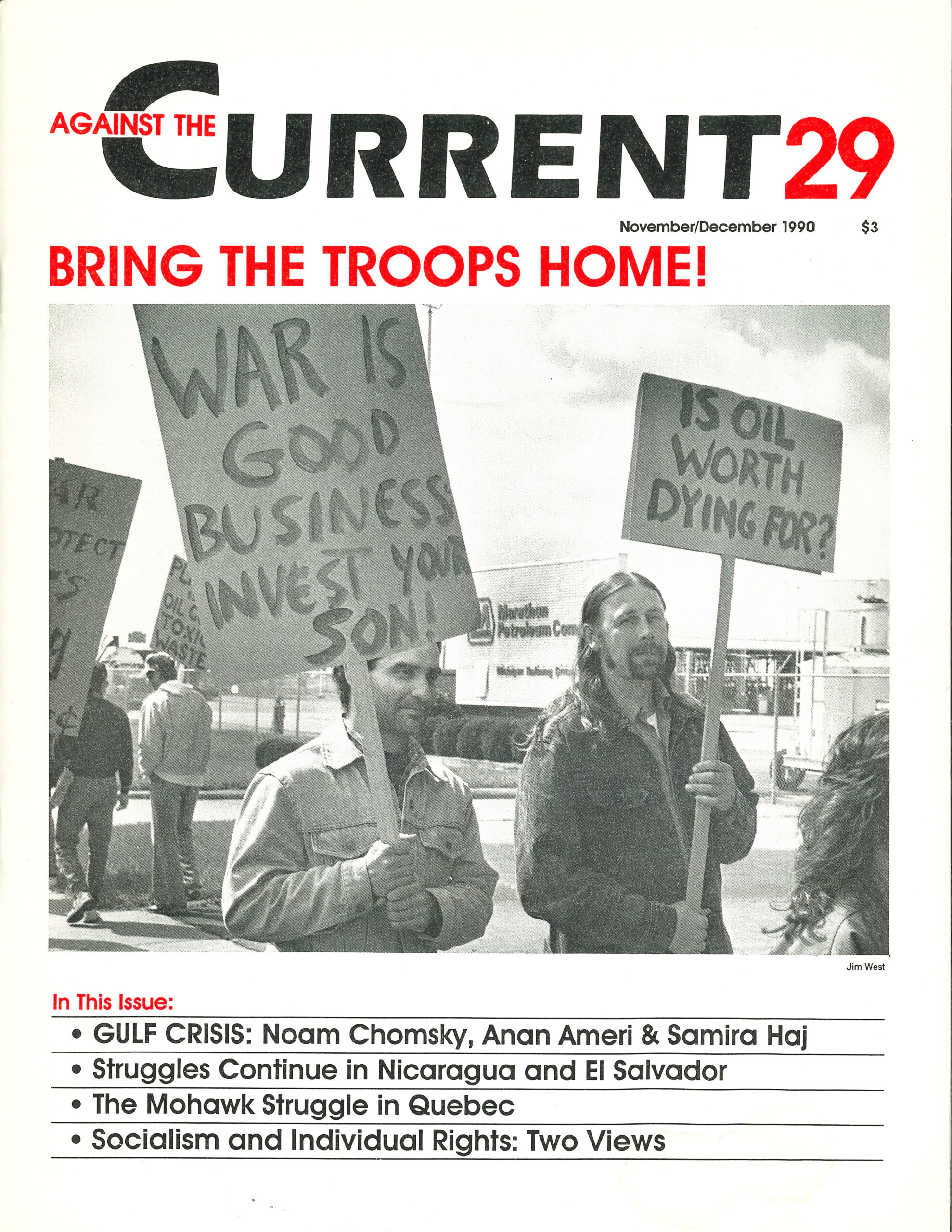

Oil Wars--The Empire Strikes Back

— The Editors -

Capital Gains Cut: Your Loss

— Erik Melander -

Is Operation Rescue Over?

— Marie Laberge -

Nefarious Aggression

— Noam Chomsky -

Statement on the Gulf Crisis

— Palestine Solidarity Committee -

The Peace Movement Responds

— Peter Drucker -

A Palestinian Perspective

— an interview with Anan Ameri -

Ba'ath Regime's Bloody Background

— an interview with Samira Haj -

Anti-communism Reaps the Islamic Whirlwind

— Shahrzad Azad -

Introduction to Socialism and Individual Rights

— The Editors -

Socialism, Justice and Rights

— Harry Brighouse -

Is Democracy Enough?

— Milton Fisk -

The Sandinistas: What Next?

— Midge Quandt -

Organizing in the Face of Murder

— an interview with Julio Garcia Prieto -

Medicine for Democracy

— an interview with Benito Vivar -

Quebec: the Mohawks' Revolt

— Richard Poulin, translated by Joanna Misnik -

The Politics of Terminology

— Richard Poulin -

Radical Feminism's Birth

— Joan Cocks -

Random Shots: The Great Gulf Oil War Follies

— R.F. Kampfer -

Letter to the Editors

— Peter Drucker

Richard Poulin, translated by Joanna Misnik

The following account was written for Against the Current immediately after the end of the confrontation between Mohawk natives and the Canadian armed finves at Kanahuske and Kanesatake, Quebec.—The Editors

ORDER HAS BEEN restored. The army and the police now control all of Mohawk territory.

Last to be subdued were some 20 Warriors and about 30 women and children cornered on a little strip of territory around 50 meters wide and 800 meters long. They surrendered on September 26 after three weeks of resisting a psychological war waged by the army.

At Kanahwake, the army and the Quebec police force laid siege to the Longhouse, the seat of the traditional government of the Agniers (or Mohawks), using the pretext that a cache of arms had been discovered there. During the dismantling of the barricades on September 1, the police and army staged repeated raids in defiance of the agreements reached with leaders of the reserve (the term used in Canada for what in the U.S. is called a reservation—translator).

It is now open season on the Mohawks. More than sixty had already been arrested even before the surrender of the last hold-outs. The worst is yet to come.

The Mohawk uprising began without fanfare on March 11. The Mohawks of Oka, Quebec tried to stop the enlargement of a golf course (planned by the town’s council to be built in a forested area held sacred by the Mohawksed.) by throwing up a barricade.

The situation heated up in July, when the provincial police intervened massively. (An armed confrontation erupted further described below, after which a second Mohawk barricade went up to block a major commuter bridge into Montreal—ed.)

The Quebecois (provincial) government, supported by the Federal (Canadian) government, claimed that negotiations were not possible while guns were drawn. The Canadian army was ordered to tear down the barricades erected at Kanahwake and Kanesatake (Oka), invade Indian territories, arrest members of the (Mohawks’) Warriors Society, and use firepower in the event of any resistance to these acts of civil war.

Much more is involved in this struggle than the issue of the arms in Mohawk hands and the barricades they erected. What is really at stake is the recognition of the national rights of the Mohawk nation, particularly territorial rights and those related to political self-determination and economic self-management.

“The law is the law,” Quebec Prime Minister Robert Bourassa and his minister of justice, Cues Remillard, reasoned ever so sincerely. But this is exactly where the conflict resides: the Mohawks do not recognize this law as their own. It is the law of the whites.

According to the treaty of parallel roads, or “Two Row Wampum” to the Mohawks: “Each of the two nations, white and Mohawk, enforce and protect their own laws, their own constitution and their own jurisdiction. Neither of these two nations can apply or impose their laws on the other.”

This is the basis for the Mohawks’ affirmation (introduced by their negotiators on August 20 in the text of the Great Law of Peace): “We are not citizens of Quebec, of Ontario, or of Canada, any more than we are citizens of New York or the United States. We have our own constitution.. the Great Law of Peace, and we belong to our own nation and our own confederation.”

Among other things, the Mohawks are demanding the unification of the present and historic territories of Kanienkehaka (the three territories of Akwesasne, Kahnawake and Kanesatake), of their nation, and everything that goes along with being a sovereign nation. This people, who have not suffered a defeat since they were allied with the British during the conquest of New France, want to negotiate a peace treaty.

Government Rejectionism

The Mohawks’ legitimacy as a long time state and nation confronted that of the whites, the legitimacy of a colonizing imperialist territorial state.

Both the provincial and federal governments refused to grant any legitimacy to the Mohawk demands, characterized them as completely far-fetched, and called the Mohawks terrorists. With help from the media, they tried to say that the community was divided between good and bad Indians (moderates and criminal radicals), as though the Warriors did not have the support of the community in which they arose.

Tom Siddon, federal minister for Indian affairs, kept singing the same refrain: “We will not negotiate at gun point on asubject as delicate as the territorial question.” As if the federal government had ever done any negotiating in the past. From the first moments of the crisis, Siddon has ceaselessly characterized the Warriors as terrorists or criminals.

For its part, the army stated definitively that it would intervene “peacefully” to obtain the Mohawks’ unconditional surrender. The only negotiations allowed would be those leading to this unconditional surrender the dismantling of barricades and turning in of weapons. A partial amnesty recommended by a commission of inquiry (demanded by the Mohawks) was rejected.

The Quebec government reneged on the humanitarian preconditions that had been negotiated (allowing food and medical supplies in, free circulation of Indian spiritual chiefs in the presence of international observers) after negotiations were abruptly broken off. The Bourassa government had provoked this break. (Robert Bourassa is the premier of Quebec–ed.)

The situation got worse for the Kahnawake civilian population, who became the starving hostages of the government. A young Mohawk from this reserve, who had been beaten by four whites in Dorval, explained to journalists that his family was living ina motel there because the scarcity of food had forced them to leave Kahnawake.

The Mohawks were afraid. They knew that when the situation was “normalized” the Quebec police force would invade their territories and make them pay dearly for their resistance. Georges Erasmus, chief of the Assembly of First Nations (the heads of the various native peoples in Canada—ed.), proposed replacing the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Force (RCMP) with a mixed force consisting of RCMP agents and police drawn from the native peoples, even though this challenged the constitutional powers conferred on the Quebec government.

The Context

The Mohawk uprising expressed the level of frustration within the most deprived social layer of the Canadian population, and their deep-seated desire to affirm their national existence.

The uprising had the support of the vast majority of the Amerindian chiefs. According to opinion polls, the majority of the Quebecois population was in sympathy with the native people The struggle of the Mohawks is only the fuse for powerful explosive that threatens to detonate at any moment in all the Canadian territories.

The potential for crisis goes well beyond the national demands of the Amerindians. It involves the constitutional dead end the country has reached.

Canada has never been so close to brealdng apart Polls taken since the rejection of the Meech Lake Accords show that a majority in Quebec favors independence This was confirmed by the recent partial elections in which pro-independence candidates won handily, garnering sixty-sevent percent of the popular vote.

[The Meech Lake Accords were a deal negotiated between the Canadian federal government and premiers of the provinces. It recognized Quebec as a “distinct society” within Canada and established mechanisms for amending the Canadian constitution, which was formally repatriated from Britain only in 1982. However, in order to take effect, the Accords had to be ratified by each of the country’s eleven provincial parliaments by last summer. The Accords were rejected because two provincial parliaments did not approve them. While extremely complex, the reasons for the Accords’ failure included both English Canadian hostility to Quebec and native people’s demands for recognition of their own distinct identity.-ed.]

The rejection of the Meech Lake Accords helped to trigger the Amerindian crisis. The provincial premiers who opposed the recognition of Quebec as a distinct society argued that the Accords had to be reopened in order to negotiate the question of rights for native people. (In 1985 and again in 1987 these same premiers had refused to negotiate constitutional rights for native people.)

When Elijah Harper, former Cree chief and an Amerindian representative in the Manitoba provincial parliament from the New Democratic Party (NDP), succeeded in blocking (Manitoba’s) ratification of the Meech Lake Accord, Amerindians throughout the country celebrated. These events gave new momentum and legitimacy to the struggle of the Mohawks at Kanesatake.

Moreover, in June, Elijah Harper’s fight against the constitutional accord cornered the Canadian government into promising to establish a royal commission to investigate the situation and demands of the native peoples. When the Accord fell through, the government withdrew this proposal. The whites really do speak with forked tongues!

For more than 500 years, the Mohawks have been demanding the territories at Oka, especially the famous pine grove that the city wanted to make into a golf course. It is considered sacred territory. The Mohawks have been demanding this area be deemed a reserve.

Every effort has been made to dislodge the Mohawks from these lands, including the creation of reserves at Maniwaki, north of Hull in Quebec, and at Gibson in Ontario. An agricultural people was offered rock-strewn land. They were refused the fertile terrain around Oka. The reserve at Gibson has failed, and the one at Maniwaki is scraping along in poverty.

The white courts were quick to grant an injunction against the barricades that were preventing the work of cutting down the pine forest The Mohawks defied this injunction.

As a result, the police could legally intervene, and they did-—with a vengeance. More than 100 Quebec Police Force (QPF) agents attacked the barricades, using heavy assault weapons, concussion grenades and tear gas. But the Mohawks answered back, aided by the Society of Warriors. They repelled the QPF during a brief shoot-out.

There was one death during this baffle, a Corporal Lemay of the QPF. It is not yet known how he was killed, or by whom. The Mohawks claim that they didn’t do it The police claim they are responsible, a formulation that tries to imply that if it hadn’t been for the barricades this policeman would still be alive.

After the defeat of their “Operation Big Stick,” the QPF, which is in the habit of brutalizing the native people, surrounded Kanesatake and prevented food supplies and medicine from getting in. The Mohawks at Kahnawake erected solidarity barricades around their reserve, closing the heavily travelled Mercier bridge (into Montreal) to traffic. Some 2000 police then encircled the reserve, depriving the inhabitants of food and medicine until the army replaced the police on August 29.

A Century of Harassment

According to Andrew Delisle, elected chief of Kahnawake for 22 years, former resident of the Association of Indians in Quebec, a founder of their national federation and a sympathizer of the Warriors, the Mohawks “have been under siege for a century.”

In 1895,1920,1922, and 1950 the Mohawks were expropriated to allow the construction of bridges, railway lines, the Saint Lawrence Seaway, etc. In 1907, the Indian Act replaced native traditional government with band leaders who had sold out to the whites.

From l9Z7 until Paul K. Diabo won a court case, the authorities sought to stop Mohawks from freely crossing the border into the United States. This prohibition violated the treaty signed in 1792 between the British crown and the young American republic. Many Indians have served six months to two years in prison because they did not recognize this law. Until 1955, Indians were forbidden to hold public meetings without the presence of the federal police or Indian affairs agents.

In recent years, the QPF and the RCMP have made frequent raids on Akwesasne and Kahnawake aimed at lotteries, bingo games and cigarette trafficking. These police raids enabled the Warriors Society to become an extremely well-organized and well-armed strike force. (The gambling operations are bitterly controversial on the reserves and led to a tragic internal struggle with at least two deaths on the Akwesasne reserve earlier this year—ed.)

Linked to the Americaii underworld, the casinos in the Iroquois territories of Akwasasne and Kahnawake are very popular because of the big purses that can be won. The lotteries are illegal according to provincial laws, which reserve to the government the right to run lotteries for big prizes.

The non-recognition of white law makes the lottery on the Mohawk reserves a privileged means of capital accumulation. In effect, a kind of primitive accumulation of capital is occurring on the reserves. This process creates strong tensions among the Warriors, the Long-house, and the band leaders elected in keeping with “Indian Law.”

However, this does not lessen the case for the legitimate and well-founded demands of the Mohawks, who are an oppressed nation. Whites can’t adopt a holier than thou attitude. It is well known that the fortune of the Bronfmans, one of the leading bourgeois families in Canada, came from running booze into the United States during Prohibition. All primitive accumulation of capital requires illegality, if not outright theft.

Wasn’t the white state in North America established through the pure and simple theft of Amerindian territories? Doesn’t that help to explain the rapid rise of capitalism in the United States and Canada? What can be challenged is the Mohawk entry into capitalist “modernity,”-—this birth of a native peoples’ capitalism-—and not the so-called “illegality” of the means used.

There are three parallel structures on the Mohawk reserves: the band council, elected by around 20% of Indian voters; the Council of the Confederation of Six Nations (Iroquois); the Longhouse, which repudiated the Warriors Society at Akwesasne, sparking the mini-civil war on this reserve.

But the border lines among the three groups are somewhat fluid. Thus the personnel on the Mohawk negotiating teams changed several limes. The government used this as a pretext to repeatedly break off negotiations, finally sending the army into Mohawk territory.

At this point, despite internal divisions, the Mohawk community is in solid support of the national demands. Obviously, the Warriors Society tried to show through its actions that it was the best group to defend Mohawk rights and thus to lead the community. This caused fierce competition between it and the chiefs of the Confederation. Despite this division, there is a goal that those who support the demands of the Amerindians of Canada hold in common: self-government.

And Now?

The Mohawk uprising occurred at a time when Canada was in a constitutional crisis. A breach has been opened by the worst crisis in national relations the country has ever undergone.

There is no doubt about the legitimacy of the Mohawk demands. From one end of the country to the other, Indians demanded their rights and took action to pressure for them, going as far as building barricades to block highways and railways.

In a country where the credibility of the Indians has always been weak, the uprising at Kanesatake and Kahnawake gave incomparable legitimacy to the demands of the native people. The national struggle of the Amerindians won broad popular sympathy, despite the deformations and misinformation.

Winning political independence and self-government for the Agniers requires the abolition of the Indian Law and the dismantling of the system of band chieftains who profit from governing in the Longhouse. The struggle is contining now, but could meet with massive repression. Because the hunt for Mohawks is now open.

Amerindian solidarity was active and strong, but solidarity from white progressive forces was weak and timid. Virulent and threatening anti-native racism reared up. It is imperative that whites mobilize massively in favor of the historic national rights of the native people. What the Mohawks are claiming for themselves is the same thing the Quebecois people are demanding: national self-determination.

November-December 1990, ATC 29