Against the Current, No. 29, November/December 1990

-

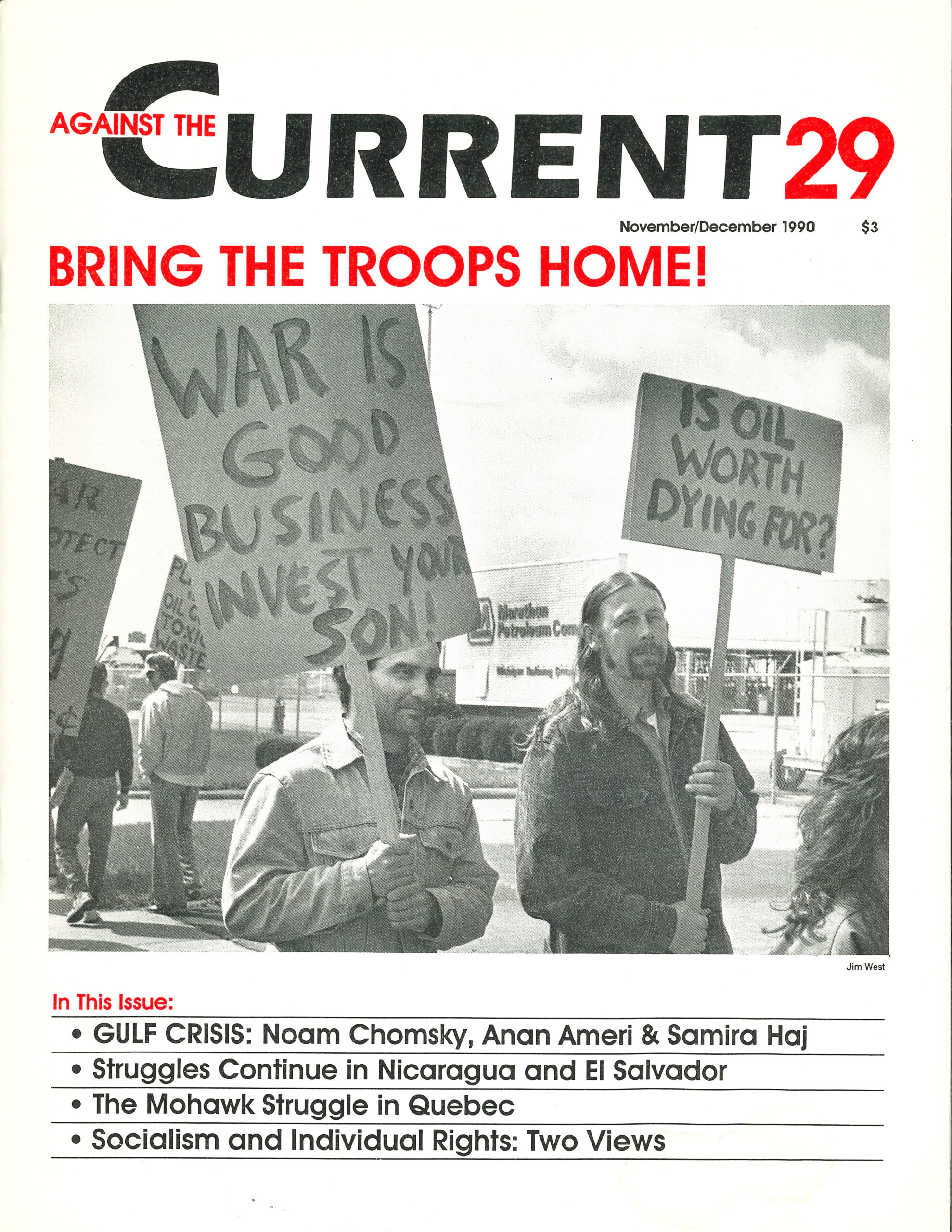

Oil Wars--The Empire Strikes Back

— The Editors -

Capital Gains Cut: Your Loss

— Erik Melander -

Is Operation Rescue Over?

— Marie Laberge -

Nefarious Aggression

— Noam Chomsky -

Statement on the Gulf Crisis

— Palestine Solidarity Committee -

The Peace Movement Responds

— Peter Drucker -

A Palestinian Perspective

— an interview with Anan Ameri -

Ba'ath Regime's Bloody Background

— an interview with Samira Haj -

Anti-communism Reaps the Islamic Whirlwind

— Shahrzad Azad -

Introduction to Socialism and Individual Rights

— The Editors -

Socialism, Justice and Rights

— Harry Brighouse -

Is Democracy Enough?

— Milton Fisk -

The Sandinistas: What Next?

— Midge Quandt -

Organizing in the Face of Murder

— an interview with Julio Garcia Prieto -

Medicine for Democracy

— an interview with Benito Vivar -

Quebec: the Mohawks' Revolt

— Richard Poulin, translated by Joanna Misnik -

The Politics of Terminology

— Richard Poulin -

Radical Feminism's Birth

— Joan Cocks -

Random Shots: The Great Gulf Oil War Follies

— R.F. Kampfer -

Letter to the Editors

— Peter Drucker

Shahrzad Azad

WE ARE TOLD that the Cold War is all but over, that the drug war in the United States has replaced the war on communism, and that communism in Eastern Europe has passed away. If the cold war and anticommunism are now “history’ as far as East-West relations go, U.S. relations with the Third World are not softening, as the invasion of Panama demonstrated. The United States continues to “confront the Third World.(1)

At the same time, the crisis of the Middle East—a multi-faceted cultural, political and economic crisis—continues to preoccupy Middle Eastern scholars, especially left-wing and secular writers.(2) The rise of political Islam in Iran, the emergence of fundamentalist movements in Egypt, Lebanon, and Tunisia, and the electoral victory in June 1990 of fundamentalists in A1eria’s first democratic elections pose a threat to secularists, socialists, and feminists in the region. Even the Palestinian movement is now infused with Islamism, while in Lebanon in 1986 a respected Communist leader was assassinated by Islamist militants.

Is there a connection between U.S. policy in the Middle East and the rise of political Islam? The Middle East has figured prominently in the first and second cold wars.(3) The proposition that the USSR is the major threat to regional stability and the supply of oil, and that any radical movement or government is in league with the Soviet Union, has been an essential tenet of U.S. policy in the Middle East policy beginning with the Azerbaijan crisis of I946.(4)

Much has been written about the consequences and costs of American imperialism in the region: the undermining of national sovereignty in the pursuit of U.S. economic interests; support for unpopular, authoritarian and violent regimes; massive arms shipments.(5) There have also been policies intended to prolong conflict and suffering rather than end 1t these include the lucrative arms flows that fueled the Iran-Iraq War and the Reagan administration’s “bleed the Soviets” and “fight to the last Afghan” policy.(6)

The focus of this article is somewhat different the contribution of anticommunism to the rise of Islamist movements in the Middle East I wish to underscore the following connections: 1) anticommunism and the diminution of secular discourse and politics; 2) anticommunism and the crisis of the left; 3) anticommunism and Islamization; and 4) the anticommunism of Western capitalist powers and that of Islamist movements.

My argument is that the persistent and unrelenting hostility on the part of Western powers, and particularly the United States, toward socialist, social-democratic, nationalist, and communist governments, movements, and ideologies in the Middle East has contributed to the decline of secular discourse and movements and the rise of political Islam, which itself is antagonistic to the left. Inasmuch as various U.S. administrations have subverted movements of the left and supported unpopular pro-U.S. regimes (as in Iran), one may speak of U.S. complicity in the emergence of Islamist movements.

Some of these movements, such as Khomeini’s, are regarded with feigned horror, while others are lauded as constituted by “freedom fighters,” as in the case of the Afghan Mujahideen. When various American pundits and academics speak of the presumed centrality and unceasing importance of Islam in the lives and politics of Middle East people,(7) they would do well to register the pattern of U.S. support for anti-communist theocrats, whether in Saudi Arabia today, Pakistan during Zia ul-Haq’s rule, or among the Afghan opposition. Thus at a time when the death of communism is being celebrated in both Eastern Europe and the West, it is worth pausing for a moment to recall the history and consequences of anti-communism in the Middle East.

A Pattern of U.S. Intervention

A cursory look at recent Middle East political history and at British and American intervention will reveal a pattern of subterfuge and subversion of left-wing alternatives. This began with the Azerbaijan crisis of 1946, was followed by the 1953 coup against Iran’s Prime Minister Mossadegh(8) and continues to this day in the form of U.S. attempts to eliminate the government of Afghanistan. Along the way there were the Eisenhower, Nixon and Carter doctrines, all predicated upon anticommunism and the protection of American interests, which evidently encompass the world.

Other examples may be enumerated: the joint British, French and Israeli invasion following Egyptian President Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1965; the 1957 Eisenhower doctrine, which offered U.S. economic aid against “armed aggression from a nation controlled by international communism” (referring to Egypt);deployment of U.S. forces in Lebanon in 1958 to support Maronite hegemony which was then being contested; hostility toward the democratic-secular project of the PLO; the Nixon Doctrine that created regional gendarmes or sub-imperialist powers, and encouraged the Pahlavi state to flex its muscles in the Persian Gulf, harass radical Arab regimes, send troops to fight the Dhofar guerrillas, and persuade the Daoud government in neighboring Afghanistan to suppress the left-wing People’s Democratic Party.

Throughout, the United States has been able to support Israel on the basis of a shared opposition to radical nationalism and back the conservative Arab states (especially Saudi Arabia) on the basis of anticommunism. The Carter Doctrine of 1980, which presented the image of an aggressive, expansionist Soviet state threatening the “free movement of Middle Eastern oil” augured the Reagan administration’s “evil empire” mentality and policy, and its obsession with “communist” Nicaragua and Afghanistan. It will be noted that the movements mentioned above were actually not communist, but more precisely nationalist or left-populist.

In the language of post-World War II bipolar geopolitics, “anticommunism” was the ideological cover for the economic and military hegemony of the United States. The discourse and policy of anticommunism conjoined ideology and material interests. According to the manichean logic of American professional anticommunists, any program for nationalization or assertion of national sovereignty in the strategic and oil-rich Middle East served the interests of the Soviet Union, was inimical to the interests of the “free world,” and was ipso facto “communistic.”

In Iran’s case the pattern of intervention by the capitalist powers predates the Cold War (And of course elsewhere in the Middle East, the Arab countries experienced European colonialism.) Iran’s Constitutional Revolution, which began in 1906, has been regarded as an incipient bourgeois revolution.(9) The British role in the emergence of the first Pahlavi ruler in 1921, however, ended republicanism and the constitutionalist movement; in 1928 Rem Than crowned himself Reza Shah.

The Azerbaijan crisis of 1945-46, which terminated a remarkable experiment in ethnic self-rule and progressive politics in a strategic province, led to the formulation of the Truman Doctrine and heralded the first Cold Wax In both cases (pre-WWII and Cold War periods), Western hostility to radical forces left an indelible imprint on Iran’s political culture. To a large extent, this shaped the outcome of the Iranian Revolution of 197879 and the post-revolutionary contest between Islamists, liberals and socialists.(10)

This pattern of Western relations with the Middle East has led one astute Syrian political scientist to observe: “The United States and Western Europe are only rhetorically committed to the modernization of the Middle East, which for them is, in reality, merely a reservoir of petroleum—that is, a vast ‘gas station’—while at the same time being unstinting in their efforts to support and strengthen the most archaic form of government in the entire region, that of Saudi Arabia, where the congruence of the sacred and the political exists in its purest form.”(11)

In an essay on the rise of political Islam, a Tunisian asserts that “Europeans and Americans have long been forced to seek the help of Islam in the suppression of embryonic social struggles in Muslim countries and in opposing their Soviet rivals.” The same author notes that at the former chief of the CIA in the Middle East, Miles Copeland, revealed in his book The Game of Nations that as early as the 1950s the CIA began to encourage the Muslim Brotherhood to counteract “communist” influence (that is, Nasser!) in Egypt.(12)

Former French President Giscard d’Estaing is said to have confided to members of his cabinet in March 1980, prior to a tour of the Gulf region: “To combat communism we have to oppose it with another ideology. In the West, we have nothing. This is why we must support Islam.”(13)

What might the political map of the Middle East look like now had the external interventions mentioned above not taken place? What alternatives were possible? In his excellent study Injustice: The Social Bases of Obedience and Revolt, Barrington Moore suggests that particular historical events (such as those of recent German history examined in his book) need not have turned out the way they did. Rather, history may contain suppressed possibilities and alternatives obscured or obliterated by the deceptive wisdom of hindsight.(14)

For Moore, it is as important to examine why something did not happen, as why something did. For the Middle East, the questions “What explains the rise of political Islam?” and “Why did the secular, liberal, or socialist alternative not emerge?” leads one to examine closely both internal and external causes. At a time when scholars and commentators refer to the presumed invariability of Islam in the culture and politics of the region, and the inevitability of certain outcomes, it is pertinent to explore causes and plausible alternatives.

We can wistfully speculate about the possibilities: an Iran that might have been neither monarchist nor Islamist a pluralist, non-sectarian Lebanon; a progressive and strong Afghan state promoting education throughout the country and fostering ethnic and gender equality Instead, these “suppressed historical alternatives” have cleared the way for an Islamist politics at a time of political turmoil, fiscal constraint and legitimation crisis throughout the Middle East.

From a Middle Eastern socialist perspective, therefore, the end result of the obsession with communism, real or imagined, with a putative Soviet “grand design” for warm-water ports, and with petrodollars, is the diminution of secular politics, the precarious state of the left, and the rise of political Islam. The persistent pattern of Western hostility to “communist” movements in the region is an important explanatory factor in the decline of left-wing movements and the rise of Islamization.

Anti-Communism: The Case of Iran

As mentioned above, the various campaigns against “communism’ in the Middle East have had both an ideological and an economic dimension True, deliberate lies were spread that distorted the real nature of nationalist and popular movements and portrayed them instead as Soviet pawns. Such was the fate of the leadership of the autonomous Azerbaijan Democratic Republic of 1945-46, and the Mossadegh government of 1951-53. But a genuine ideological battle was underway, too, in which civilized, cultured and superior Westerners were pitted against uncivilized, uncultured and inferior communists and Orientals. In this regard, the anticommunist/Cold War discourse has strong parallels with the Orientalist discourse.

In his anonymous 1947 article in Foreign Affairs, George Kennan, one of the architects of the Cold War, contrasted the Russians’ Oriental “mental world” with that proper to the “Western” mind:

“Their particular brand of fanaticism, unmodified by any of the Anglo-Saxon traditions of compromise, was too fierce and too jealous to envisage any permanent sharing of power. From the Russian-Asiatic world out of which they had emerged they carried with them a skepticism as to the possibilities of permanent and peaceful coexistence of rival forces…. Here caution, circumspection, flexibility and deception are the valuable qualities; and their value finds natural appreciation in the Russian or the oriental mind.”(15)

The economic dimension is fairly straightforward. The Western powers have viewed the Middle East primarily as the major source of energy supplies and therefore as being important to the West’s economic wellbeing and national security.(16) The capitalist powers have always wanted to maintain and perpetuate the international economic order originally founded and developed by Europeans.(17) Thus, while still a world power, Great Britain persistently violated Iranian sovereignty and undermined the economic well-being of Iranians (and why not, as they were deemed to be inferior to the English) through its control over Iran’s oil industry.

It was this ideological imagery and economic interest that rendered the British unwilling to accept a reduction of their control of Iranian oil and profits and outraged when the Iranian Parliament moved to nationalize the oil industry in 1951. In retribution, the British government organized a boycott and precipitated an economic crisis in Iran.

Egged on by his conniving twin sister and the mysterious American General Schwartzkopf, the Shah tried to sack Premier Mossadegh. Nationalist and Communist agitation led the Shah to flee the country in 1953; by now the nationalists were calling for constitutional monarchy and a kind of non-alignment while the Communists (the Tudeh Party) favored a republic and a friendlier stance toward the Soviet Union. The CIA, with the Iranian military, brought about the Shah’s restoration.

A further twist to this tragic story is that Mossadegh’s own anticommunism led him to distrust the Soviet Union, distance himself from a potential ally, the Tudeh Party, and turn to the United States for mediation and resolution of the conflict with Britain. It was still too soon after the onset of the Cold War for Mossadegh to comprehend its full ramifications and the new shape of inter-imperialist rivalry. For its part, the Eisenhower administration took advantage of the conjuncture to do away with an independent-minded government in a strategically located oil-producing country and secure its own ascendancy as the hegemonic world power.

Consequences of the 1953 Coup D’etat

The CIA-sponsored coup of August 19, 1953, has been extensively researched,(18) but the link between the coup and the emergence of the Islamist state in 1979 has not been adequately appreciated. Gasiorowski, however, begins his interesting study by noting that the U.S.-sponsored coup d’etat was a critical event in postwar world history.

“The government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq, which was ousted in the coup, was the last popular, democratically oriented government to hold office in Iran. The regime replacing it was a dictatorship that suppressed all forms of popular political activity, producing tensions that contributed greatly to the 1978-79. Iranian revolution. If Mosaddeq had not been overthrown, the revolution might not have occurred … .[It] made the United States a key target of the Iranian revolution.”(19)

Following the restoration of monarchical rule, an “iron curtain” of sorts fell on Iranian politics. In the words of Abrahamian: “It cut the opposition leaders from their followers, the militants from the general public, and the political parties from their social place.”(20)

Mohammad Reza Shah’s subsequent reign saw the establishment of state-sponsored parties for the purposes of support and control. In the preoccupation with ending nationalist and communist influence, the Pahlavi state eliminated the parties and leaders from the political terrain and denied the left any space in the cultural realm. For twenty-five years the Iranian left was banned and hounded. Small wonder that the left came to the revolution with limited resources and cadres. The Islamist establishment, however, had been allowed to retain its own political and cultural institutions, and was permitted access to state-controlled organizations, notably the mass media.(21)

This is not to suggest that the U.S. government, or the CIA, were aware of the power of the Islamic establishment—far from it In fact, according to Bob Woodward, the CIA had studiously misread Ayatollah Khomeini as “a benign, senile cleric.”(22) Conversely, but typically, it exaggerated the strength and influence of the Tudeh Party and that of the Soviet Union in Iran.

In light of all this, Ayatollah Khomeini’s appellation of the United States as the “Great Satan” is understandable. Iranian anti-Americanism is a rational response to a consistently interventionist foreign policy. Most Iranians will find it hard to ever forgive the United States for the coup against Mossadegh.

Unfortunately for the left, but inevitably given the nature and objectives of political Islam, Khomeini extended his Manichean world-view to encompass “Marxists, communists, materialists, atheists,” etc. He refused to cooperate with them in the struggle against the Shah (even though other Islamists did work with leftists) and eventually led a holy war against the communist organizations.(23)

Khomeini’s anti-communism had an ideological and a political—but not economic—dimension: he was resolutely against secularism, and he regarded the left-wing organizations as either pawns or flunkies of the Soviet Union or of “the West.” Thus the Tudeh Party leaders and members arrested and tried in 1983 were all charged with treason, spying for the Soviet Union, undermining the Islamic Revolution and state, and seeking to import and impose an alien ideology.

An ironic and tragic twist to this story is: a) the Tudeh Party had wholeheartedly supported Khomeini as an “anti-imperialist” rather than helping to build an alternative socialist agenda and movement; and b) the CIA furnished the regime—with whom the United States had no relations—with the names of some 200 Tudeh members, who were subsequently arrested and many of them executed.

David Newsom, a former U.S. under-secretary of state, remarked with some satisfaction: “The leftists there [in Iran] seem to be getting their heads cut off.” Anti-communism makes for strange bedfellows, as Irangate subsequently demonstrated.(24)

It is hardly necessary to repeat that the crisis of the left in Iran has important internal sources, which have been explored elsewhere in depth.(25) For Afghanistan, Raja Anwar does an excellent job of analyzing the internal causes-as well as the external sources-of the PDPXs crisis and of the armed revolt of the Mujahideen.(26) The left in Iran and Afghanistan, as well as in Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt and elsewhere, must take responsibility for mistakes and shortcomings in their theoretical formulations and their political practices.

This article has sought to direct attention to the external factor, an under-researched aspect of the rise of political Islam. The American obsession with fighting communism, protecting the oil interests of the so-called free world, and maintaining its hegemony is crucial in understanding the decline of the left, the diminution of secular discourse and politics, and the strength of the Islamist alternative. East Europeans may today be concerned about how Communist policies have affected their economies and purchasing power, but in the Middle East, the impact of the various crusades against communism has been far more problematical.

Notes

- Gabriel Kolko, Confronting the Third World (New York: Pantheon, 1988).

back to text - See All Ashtiani and Val Moghadam, “Does the Left Have a Future in Iran? Contending with Political Islam” (mimeo, 1990); Hisham Sharabi, Neopatriarchy: A Theory of Distorted Change in the Arab World (New York) Oxford University Press, 1988); Bassam 111, 1, The Crisis of Modern Islam (Salt Lake City, University of Utah Press, 1988).

back to text - Fred Halliday, The Making of the Second Cold War (London: Verso, 1988).

back to text - See Gabriel Kolko, The Polities of War (New York, 1968). On the Azerbaijan crisis, see Richard Cottam, Iran & the United States: A Cold War Case Study (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1988); Fred Lawson, “The Iranian Crisis of 1945-46 and the Spiral Model of International Conflict,” International Journal of Middle Last Studies 21 (August) 307-326.

back to text - Bahman Nirumand, Iran: The New Imperislism in Action (New York: Monthly Review 1969); Leila Meo, ed., U.S. Strategy in the Gulf: Intervention Against Liberation (Belmont, MA: Association of Arab-American University Graduates, 1981); Naseer Aruri, Fouad Moughrabi, and Joe Stork, Reagan and the Middle East (Belmont, MA: Association of Arab-American University Graduates, 1983); Michael Klare, American Arms Supermarket (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1984).

back to text - Selig Harrison, “Afghanistan: Soviet Intervention, Afghan Resistance, and the American Role,” in Michael Kiare and P. Kornbluh, eds., Low-Intensity Warfare: Counterinsurgency, Proinsurgency, and Antiterrorism in the Eighties (NY: Pantheon,. 1988); Val Moghadam, “Afghanistan at a Crossroad: Retrospect and Prospects,” Against the Current, (November-December 1988); Fred Halliday, From Managua to Kabul (London: Verso, 1989).

back to text - See, for example, Robin Wright, Sacred Rage: The Wrath of Militant Islam (New York Simon & Shuster, 1986).

back to text - See Richard Cottom, Nationalism in Iran (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1979).

back to text - Ervand Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982).

back to text - This theme is explored further in the following essays by Val Moghadam: “Socialism or Anti-Imperialism? The Left and Revolution in Iran,” New Left Review 166 (November-December 1987), and “One Revolution or Two? The Iranian Revolution and the Islamic Republic,” Socialist Register (1989).

back to text - Tibi 31.

back to text - Lafif Lakhdar, “Why the Reversion to Islamic Archaism?,” Jon Rothschild,ed., Forbidden Agendas: Intolerance and Defiance in the Middie East (London: Al-Saqi, 1984) 289.

back to text - “The President in the Land of 1001 Wells,” LeCanard Enchan (March 6, 1980) quoted in Lakhdar 289.

back to text - Barrington Moore, Injustice: The Social Bases of Obedience and Revolt (White Plains, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1978), chapter 11.

back to text - Quoted in William Pietz, “The ‘Post-Colonialism’ of Cold War Discourse,” Social Text 19/3) (Fall 1988) 59.

back to text - Petter Nom and Terisa Turner, eds., Oil and Class Struggle (London: Zed, 1980).

back to text - Immanuel Wallerstein, The Capitalist World-Economy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1979). Today’s global realignment merely expands the North to include other Europeans (Central/East Europeans) while the long-standing issues of North-South economic justice and redistribution remain unresolved and unchanged. Today’s world order also means that the United States can invade Panama with impunity, but the invasion of Kuwait by Iraqi troops will be met by economic embargoes and, in the sanctimonious language of President Bush and Prime Minister Thatcher, a resolute response by all civilized nations.

back to text - See Cottom, 1979, 1988; Abrahamian 1982; Mark Gasiorowski, “The 1953 Coup D’etat in Iran,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 19 (August 1967) 261-286.

back to text - Gasiorowsld 261. He goes on to note that the 1963 coup also marked the first peacetime use of covert action by the United States to overthrow a foreign government. As such, it was an important precedent for events like the 1954 coup in Guatemala and the 1973 overthrow of Salvador Allende in Chile.

back to text - Abrahamian 431.

back to text - See Shahrough Akhavi, Religion and Politics in Contemporary Iran (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1980); Said Amir Arjomand, The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran (New University Press, 1988).

back to text - Bob Woodward, Veil: The Sacret Wars of the CIA 1981-87 (New York Pocket Books, 1988) 11.

back to text - This was in addition to the war against the Mojahedin, which was far more brutal, because the Mojahedin took up arms against the Islamist state. See Ervand Abrahamian, The Iranian Mojahedin (New Haven, Ct: Yale University Press, 1989).

back to text - See Cheryl Rubenberg, “U.S. Policy Toward Nicaragua and Iran and the Iran-Contra Affair: Reflections on the Continuity of American Foreign Policy,” Third World Quarterly 10, 4 (October 1988) 1467-1504.

back to text - In addition to the essays in footnote 11, see Val Moghadam, “The Left and Revolution in Iran: a Critical Analysis,” in Hooshang Amirahmadi and Manucher Parvin, eds., Past-Revolutionary Iran (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1988).

back to text - Raja Anwar, The Tragedy of Af8hanktan (London: Verso, 1988).

back to text

November-December 1990, ATC 29