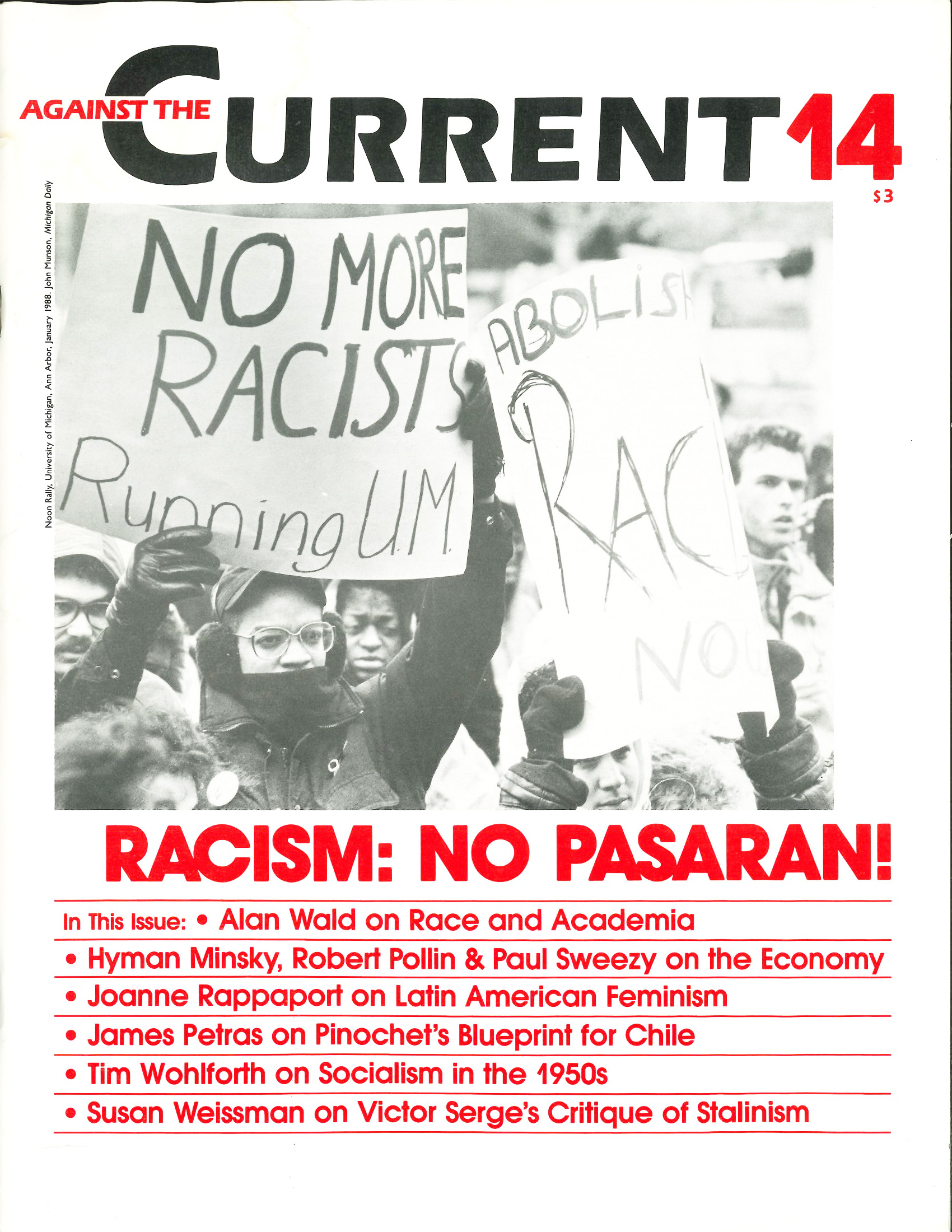

Against the Current, No. 14, May/June 1988

-

From Locked Out to Locked In?

— The Editors -

Our Heroes, As We See Them

— Sol Saporta -

Eyewitness to the Palestinian Uprising

— an interview with Marty Rosenbluth -

Latin American Women: "We're All Feminists"

— Joanne Rappaport -

Chile in 2000: The Generals' Blueprint

— James Petras -

Revolutionaries in the 1950s

— Tim Wohlforth -

Victor Serge's Critique of Stalinism, Part II

— Suzi Weissman -

Random Shots: The Bones Break, the Clubs Hold

— R.F. Kampfer - Resisting the New Racism

-

Racism and the University

— Alan Wald -

South Africa's Media Scam

— Dianne Feeley - The Economy & the Crash

-

After the Crash: A New Stage?

— Frank Thompson -

Accumulation Leads to Crisis

— Paul Sweezy -

Who's Been on a Binge?

— Robert Pollin -

In a World of Uncertainty

— Hyman P. Minsky - Review

-

What Makes Things Change?

— Tony Smith - Dialogue

-

Against Radical Mythology

— Peter Drucker -

The Power of Radical Religion

— Ken Todd - Letters to the Editors

-

Clarify Palestinian Self-Determination

— Charlie Post -

Market Socialism through Socialist Feminist Analysis

— Ilene Winkler

James Petras

AUGUSTO PINOCHET, in power since the 1973 overthrow of the democratically elected Socialist government of Salvador Allende, is establishing the basis for the continuation of his rule into the twenty-first century. Pinochet’s 1980 constitution, established on the basis of a rigged plebiscite, calls for a yes-or-no ballot by early 1989 on a single presidential candidate to be selected by the chiefs of the armed forces and Pinochet If the candidate is approved by the voters, he/she would serve an eight-year term. If he/she is rejected, arrangements would be made for a broader election.

Pinochet is intent on securing nomination by the generals and winning the elections. He is proceeding, however, to formulate a comprehensive ideological-institutional strategy that goes far beyond the elections. This strategy was spelled out in detail by a series of secret documents prepared by the Ministry of the Interior and presented to a closed meeting of more than 300 mayors on Aug. 10-12, 1987, in the resort city of Vina del Mar. I received a copy of these documents from a source in Chile.

The documents comprise two sections. The first, “Problems Presented by the Socio-political Evolution of Chile,” is followed by a series of working papers designed to guide the mayors’ plan of action. Surprisingly, the political analysis is quite sophisticated and, at times, explores significant issues that have relevance to contemporary Chile, even if the ultimate purpose is to buttress the dictatorship.

Moreover, the documents reveal a real concern with developing grassroots organizations and, in doing so, puts its finger on the basic weakness of the political opposition: its lack of firm roots in the daily struggles of the poor.

Opposition critics of Pinochet have unfortunately focused only on the electoral ambitions behind Pinochet’s proposals of municipal reforms and have failed to grasp the long-term, large-scale institutional changes found in the documents, which are more important to the future development of Chile.

These institutional changes are grounded on a comprehensive interpretation of Chilean history, the crisis that led to the military coup and the various stages in the regime’s effort to build a “new order” that will last into the foreseeable future. This historical-ideological analysis lays the basis for the regime’s first serious efforts at mass organization and political institutionalization since the coup; it does not merely promote the leaders’ desire to win the 1989 elections.

The timing of Pinochet’s push for institutionalization is propitious. The popular upsurge and mass protests of 1983-86 have ebbed, and the regime has been privatizing health, education and housing services, while proposing a program of administrative decentralization in which the municipality theoretically becomes a center of power. In practice the mayor appointed by the regime controls all decisions. The dual effect of privatization and decentralization is designed to diminish the pressures on the state and to allow for more efficient control of the grassroots. These reforms are part of a larger process of change entitled “The National Civic Plan,” which is designed to legitimate the regime during its transition and consolidation.

“Intellectual Elite” vs. the “Real Nation”

According to the Pinochetist documents’ version of Chilean political history, there has been a divorce of the “intellectual elite” from the “real country” formed by the common people. To bolster this notion of a historical cleavage, the regime cites the lack of communication between the two and the elite intellectuals’ use of a language and theory of power and values that are contrary to the “objective interests of society.”

This divorce is, according to the documents, the source of all of Chile’s problems. It has led to: (1) excessive ideologizing and partisan party politics generating “party-cratic tyranny,” which in turn has led to sweeping ideological recipes purporting to solve every problem, but which are at the margin of factual reality and the “natural composition” of society; (2) foreign interference in national problems, since the ideology is generally “imported” and the product of international party alliances; (3) the interpenetration of parties and intermediate groups, which distorts the proper goals of both.

The result is an artificial division among Chileans and a serious threat to national unity as Chileans have abandoned constructive paths and “reduced” all problems to questions of “power,” “structure” and the “conquest of power;” in which each election called into question the very existence of Chile as a Western Christian nation.

Alongside these political defeats, the regime diagnosis points to the extreme poverty in which 20 percent of Chileans live-a condition, it argues, incompatible with “true democracy.”

This diagnosis argues that the prior constitutions were inadequate in solving basic problems, particularly those concerned with the use and abuse of presidential and state bureaucratic power; they ignored the institutional significance of the armed forces and the possibilities of autonomous expression by the intermediary social bodies “”between man and the state.”

Finally, the document points to the political importance of the Communist Party in Chile-in contrast to other countries-emphasizing that it remains a permanent threat to the nation.

The document cites these as the problems that face the “real nation” and proceeds to impute to it the political agenda of the military regime: a strong president as the true arbiter of the people-beyond the reach of parties and special interests; direct participation of the natural social groupings (estamentos) in their own proper depoliticized channels; a unifying nationalism that provides cohesion and overcomes social divisions.

There follows a periodization of Chilean political history in which the periods of authoritarianism (1831- 61) are praised and the parliamentary periods are damned. These culminated in the definitive collapse of the system (1964-73) under the aegis of the totalitarian “demo-Marxists.”

The collapse of parliamentary politics led to the establishment of a “new order” that the document describes as being contrary to the expectations of the old parliamentary right. This wing represented the discredited artificial “political elites” who saw the coup as a means of restoring the previous parliamentary system with themselves in command.

Rather than a restoration, the coup is described by the document as the beginning of a process of foundation-building that, while lacking a precise ideology, was “loyal to our roots and our authentic tradition as a Hispanic, Western Christian nation,” and would express the real Chilean nation.

With these concepts as the historical background, the document proceeds to identify the stages through which the military regime has passed. The first stage, 1972-1982, is denoted as the period in which the political and economic system was “sanitized.” This included the eradication of terrorist organizations, restarting the economy, establishing basic democratic rights and the independence of natural autonomous organizations.

The second stage, 1982-1990, is described as characterizing the “transition” from the “sanitized state” to authentic democracy. With the third phase, starting in 1990 and with no termination date given begins the period of consolidation of the new institutions.

In case there is any doubt about the role of the military, the documents state that “the responsibility for overseeing the correct functioning of the system and guaranteeing the institutions … corresponds to those who originated the process and were its principal actors, the Armed Forces ” In a word, the military will continue effectively to rule for an indefinite time period — beyond the twentieth century. The stages of dictatorial military rule ultimately are legitimated through resort to the nacion real — the real nation, whose problems and aspirations are being resolved in this process.

The regime ideologists are not themselves mystified by their own notions, nor are they unaware of the overt and latent hostility they will encounter en route as Pinochet pursues victory in plebiscites and presidential elections: “The social [transitional] stage will not be a harmonious one in which there exists a consensus over the rules of the game. On the contrary, what is at stake is the very existence of the regime, the values and principles that conform to the doctrinal framework that inspires us.” In order to gain that support, the document describes a Civic Action Plan that will carry the regime to the twenty-first century.

The Civic Action Plan: Theory and Practice

In a number of instances the socio-political critique of liberal and social democracy that is present in the document has more than a grain of truth: the political class did not always respond to the lower classes; they did frequently pursue political power for its own sake; liberal constitutionalism did not address the social inequalities or provide a forum in which the issues of extreme poverty could be resolutely tackled. Parties did instrumentalize “intermediary organization/’ subordinating their demands to electoral contests. Popular and political discourse did not always anchor itself in the everyday struggles of the poor.

The Pinochet document, then, appears to borrow a critique of capitalist democracy from the extra-parliamentary left and harness it to its own version of the state in which all the same criticisms of elitism, foreign ideologies, and lack of independence of intermediary groups are even more strikingly on target. Pinochet’s state has committed gross abuses of power not only against the political elites, but even more against the common person — puro Chileno, the “real nation”-whom the document ostensibly represents.

A close reading of the National Civic Plan clearly reveals that the entire intellectual discourse of the Pinochet regime is nothing but a thin verbal gloss over a grab for power in 1989 and a continuation of dictatorial rule thereafter. What is new, however, is that the regime is using the Civic Plan to systematically construct a vertical network of mass organizations, linked to the state through appointed mayors, to sustain Pinochet’s rule. This network relies on computer studies of the politico-ecoomic profile of each municipality, a substantial infusion of state funds into “local leadership training” and the long reach of the state to “neutralize” opponents.

In the first instance, the Action Plan speaks of a “will to power, will to win”-clearly the old parties are not the only ones who speak or write of power. More specifically, the Civic Action program’s “will to power” has the “explicit objective” of providing “evidence of majoritarian and unresistable Chilean adhesion to the government.” The document then characterizes the role of the Pinochet-appointed mayors in their communities in the coming years as “political.” So much for the virtues of the depoliticized, non-ideological “real nation.”

In order that the mayors can carry on the regime’s political organizing in the municipalities, the Ministry of interior is delegated the job of allocating and organizing financial and administrative resources. The mayors, pivotal figures in this process, are told that their position demands that they have a “personal commitment to the values and principles of the regime, and to the government as instruments for its consolidation and to his Excellency the President of the Republic regarded as the legitimate conductor of this process….” In a word, the mayors are to be apparatchiks-hardly the autonomous agents of intermediary social organizations.

The National Civic Plan is purportedly designed to deal with the new structure, social relations and challenges that the document correctly notes are significantly different from those that existed earlier and which the opposition parties and leaders have failed to come to terms with. Yet, once again, while Pinochet is an effective and clever critic of the inadequacies of the opposition, his own programs and plans are far more irrelevant, repressive and distant from the aspirations of the new generations emerging in Chile.

The diagnosis attacks the abuses of the liberal state, while the National Civic Action plans greater abuses; the diagnosis attacks poverty, while the Pinochet regime has multiplied it; the diagnosis speaks of limiting the state, and the plan projects extending the powers of the state to every comer of civic society; the diagnosis speaks to the autonomy of intermediary bodies from parties, while the plan formulates a strategy to subordinate them to the state; the diagnosis attacks the over-politicization and over-ideologization under previous regimes, while the plan calls for extending indoctrination to every recipient of a soccer uniform, every neighborhood activist, through a vast network of “leaders” directed by the Ministry of the Interior.

The Civic Action Plan identifies housewives as a key constituency to which it is directing its policies. Yet, at least in the lower-class poblaciones (neighborhoods), recent surveys have found that 40 percent of the leaders of local neighborhood organizations mobilizing in opposition to Pinochet’s housing program are women. While many lower-class women may be alienated by the wheeling and dealing of the opposition’s middle-class lawyers, they are out in the streets erecting barricades against Pinochet’s armed personnel carriers invading the barrios.

The Civic Action Plan cites a survey conducted by the opposition in which only 15 percent of the respondents identified political concerns as most relevant compared to 55 percent citing economic problems. This survey is used to demonstrate that Chileans are not interested in the electoral agenda but in “concrete socio-economic problems.” What Pinochet’s ideologues forgot to mention is that it is precisely his disastrous free-market economic policies that have created the desperate conditions in which people struggle to sustain themselves from day to day.

What is crucial, however, is that Pinochet is directing his mayors and his resources to precisely these grassroots “socio-economic” issues in order to build up his electoral clientele. The bulk of the opposition, on the other hand, has opted for a strategy of social demobilization and is focusing almost exclusively on the single issue of “free elections”-likely to be a fatal strategy in the run up to the elections. The concluding section of the Mayors’ Congress was oriented toward the practical organization of a national grassroots network to ensure the efficacy of the Civic Action Plan.

The rigid totalitarian reality assumed by the plan contrasts strikingly with the direct democracy rhetoric of the earlier introductory political analysis: “This battle of ideas demands, in part, a solid preparation of the mayor and his collaborators in doctrinal materials and imposes the necessity of basic definitions expressed in a uniform language for all the authorities at all levels.”

The totalitarian strain in the regime’s new organizational drive is evident in the criteria by which the mayors are told to select their “homogeneous” teams: “(a) degree of adhesion to the government; (b) professional formation; (c) capacity for action; (d) spirit of sacrifice.” The plan underlines the centrality of the political role of the mayors: “It is precise to establish with clarity that during the next three years, the political work of seeking supporters must be paramount in relation to the administrative.”

All community leaders “must be carefully selected and base themselves in the public works of the government.” From the granting of material improvements (habitations, schools, clinics, paved streets) to other types of action (scholarship, sports equipment, social benefits) there must be “a process of selection, registration and training of leaders.” These leaders then are to be assigned “to penetrate all sectors of civil society” and coordinated and directed by the municipal authority in conformity with the Civic Action Plan.

In the area of mass communication, the Civic Action Plan calls for greater efforts to homogenize the media behind the “necessity to attain a loyal majoritarian citizen commitment.” On the other hand, the plan calls for greater repression of the opposition: “In each municipality, organized centers exist that articulate these campaigns (critical of the regime) and that must be located, put under permanent surveillance, their actions analyzed and neutralized in an adequate manner.”

The term neutralized, of course, evokes the sinister language of the international terror networks of the 1970s and, in particular, the CIA manual on political assassination published for the contras a few years ago.

The mayors are to establish a grassroots informer network to collect information on the opposition’s means of communication and those individuals who provide financial support through commercial ads. This process is to be accompanied by “public denunciations… of whatever opposition action is contrary to the interests and program of the municipality.” The net is wide enough to reach any critic, and the powers of the mayor, backed by Pinochet’s secret police, are broad enough to undermine any campaign organized to defeat Pinochet’s electoral ambitions.

And that is precisely what is intended by this section of the plan, which bears the title “The Opposition’s Credibility must be Neutralized.” In Pinochet’s depoliticized politics, “authentic democracy” and “real countries” don’t have oppositions-least of all among the squatter settlements and neighborhood organizations that have bypassed the official opposition in challenging the regime.

The definition of the mayor’s dual role of regime promoter and political cop-“the basic job of the mayor is to detect, identify … in general thoroughly know political groups that act in the municipality, as well as their leaders”-is accompanied by the regime’s effort to differentiate among the opposition.

The Civic Action Plan distinguishes between three types of opposition. The first comprises “anti-system” groups that want to replace not only the government but also “the present form of the state.” Against this group, the dictatorship calls for “intransigent struggle… and the creation of all possible obstacles to their action.”

Relatively moderate opposition groups, “which include groups that recognize the bases of the institutions as valid but are characterized by a clear doctrinal opposition … they do not want to replace the state . . . [but] the government.” This group should be tolerated but kept under surveillance.

The third type are groups that are partisans of the government. With regard to these groups the mayor is instructed to be “neutral . . . in dispensing state resources to all without sectarianism.”

It is evident from this account that the regime has a clear understanding of the difference between oppositionists who want to reform the political-legal system and retain many of the socio-economic structures that Pinochet has put in place and those oppositionists who want to change both the authoritarian political system and challenge the privileged socio-economic classes that have emerged. In drawing the distinction between opponents who wish changes in regime and state and gauging their repressive policies accordingly, Pinochet’s advisors are able to drive a wedge between the center and the left at the expense of both.

The whole structure and politics of the Civic Action Program at the municipal level is saturated with the narrow political goals of the Pinochet dictatorship-from municipal investments to hiring school teachers to designing school curricula. The task of the mayor, “particularly with teachers in the humanities,” is to ensure “their commitment to the broad doctrinal principles of the regime” and to make them work in a political educational front based on the regime’s doctrine.

Even in the selection of leaders in sports, the mayor is directed to “raise their doctrinal levels in an adequate form,” linking the expansion of sporting activities to support for the regime. Where juntas de vecinos (neighborhood councils) exist, the mayor is to be given power “to modify [their] jurisdictional boundaries” and “to designate the leaders of these organizations.”

Conclusion

The scope and breadth of Pinochet’s National Civic Action Plan entail a number of significant changes in Chilean politics. First of all, Pinochet is actively organizing to compete with the opposition at the grassroots level. Then, he has mounted a formidable political apparatus at the municipal level, backed by the purse strings of the national government and the coercive power of the state.

Furthermore, he has developed a comprehensive ideological vision-deeply flawed and totally at odds with his practice-that plays on ce1tain populist and even “direct democracy” strains in Chilean popular culture.

He has seized the political initiative from his political adversaries and shifted the ground of political competition from the terrain of electoral to socio-economic issues. And finally, he has tied his electoral fortunes to the institutional and class changes that resulted from the overthrow of the socialist government, changes that have created strong pressures for a positive response from all those who felt themselves “part” of the new order, regardless of how much or, more accurately, how little they benefitted.

With the formidable power of the state at his beck and call, with the highly politicized quasi-totalitarian “mass organizing” he has undertaken, Pinochet shapes up as a difficult candidate to beat in the run-up to the elections. Unless the “centrist” opposition can shed its inhibitions about mass mobilization, dispense with its politics of buttonholing dissident generals and shed its illusions about Undersecretary of State Elliott Abrams as an ally of Chilean democracy, it is in deep trouble.

The campaign to defeat Pinochet’s effort to extend his rule into the twenty-first century will be won or lost in the streets of Santiago; in the struggles of the urban poor over housing, jobs and food; among the educated young without a future. Pinochet has thrown down the gauntlet. He has challenged the opposition to battle over the loyalty of the young, the women and the poor in the economy, culture and politics.

The question is whether the various segments of the Chilean opposition can rise to the occasion, bury their differences, take off their neckties and begin the nitty-gritty task of linking everyday struggles over empanadas y porotos (meat pies and beans) with the struggle for free and open elections.

May-June 1988, ATC 14