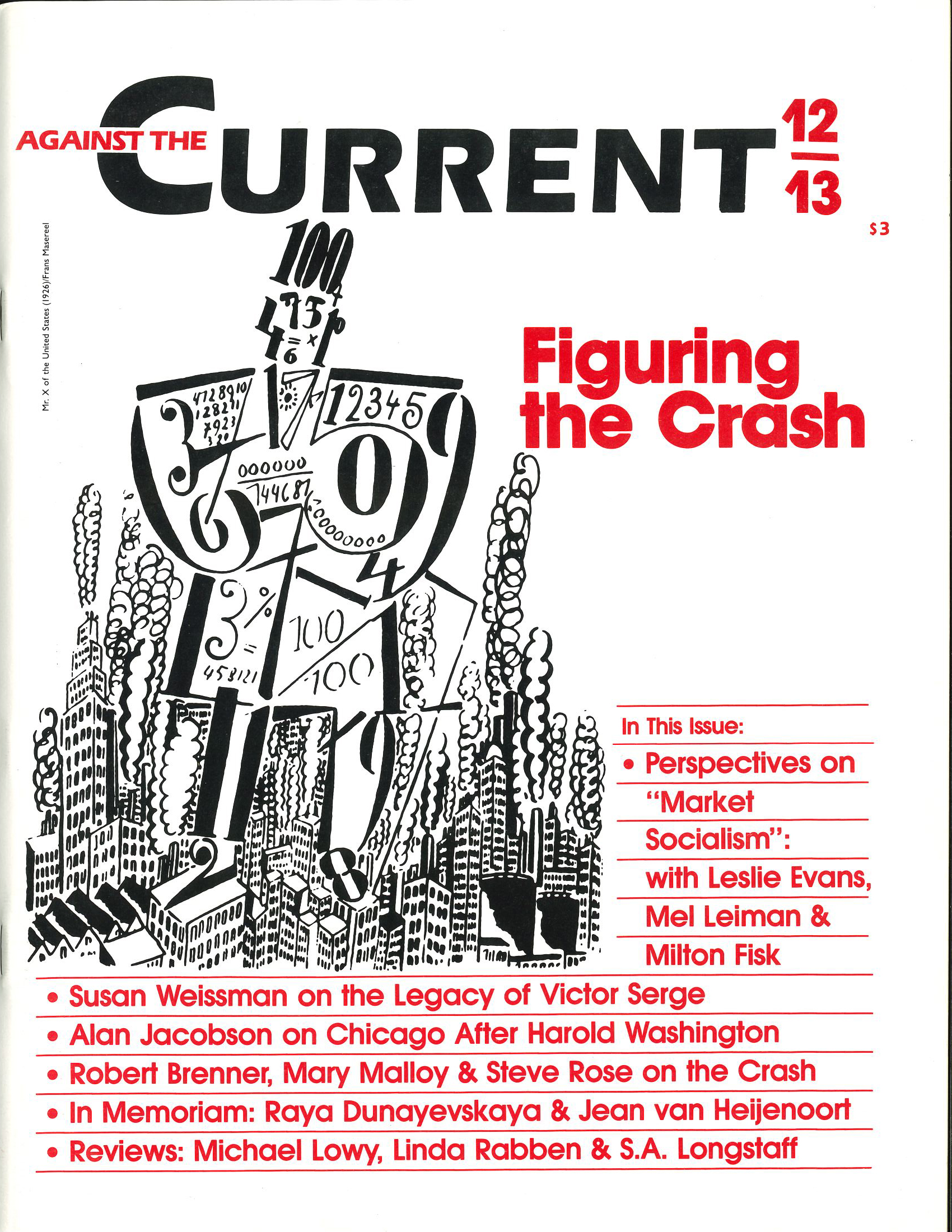

Against the Current, No. 12-13, January-April 1988

-

Occupation in Permanent Crisis

— The Editors -

The Washington Legacy: Council Wars in the Windy City

— Alan Jacobson -

"New Period? A Letter to the Editors

— Steve Downs -

Victor Serge's World and Ours

— Susan Weissman - Clear the Names of the Moscow Trial Victims

-

Random Shots: Potato Head Blues

— R.F. Kampfer - After the Crash

-

Notes on the Crash and Crisis

— Robert Brenner -

Why a Crisis of Profitability?

— Mary Malloy -

Another View of the Economy

— Steve Rose - Market Socialism

-

Market Socialism: An Overview

— David Finkel with Samuel Farber -

The Limits of Socialist Planning

— Leslie Evans -

Legacies of Soviet Planning

— Mel Leiman -

A Matter of Priorities

— Milton Fisk - Memorial Essays

-

Raya Dunayevskaya: Thinker, Fighter, Revolutionary

— Richard Greeman -

Van Heijenoort Remembered

— Alexander Buchman - Reviews

-

A Haymarket Memorial

— Michael Löwy -

Body of Opinion

— Linda A. Rabben -

Radicalism in the Forties

— S.A. Longstaff - In Memoriam

-

Raymond Williams, 1921-1988

— The Editors -

Nora Astorga: ¡Presente!

— The Editors

Michael Löwy

Haymarket Scrapbook

edited by Dave Roediger and Franklin Rosemont

Chicago, Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, 1986. $29.95 hardback,

$14.95 paperback.

WALTER BENJAMIN once wrote that the memory of the martyred ancestors is one of the most powerful sources of inspiration for social movements and revolutionary struggles. To keep alive in the labor movement the memory of the Chicago events of May 1886 and of the five revolutionaries victimized by class injustice, is not only a work of historical justice but also a militant political action. This is particularly true in relation to the United States, where the ruling class has tried by all means to bury that memory by presenting the May 1 as some sort of official Soviet event, a parade in Moscow attended by the Politburo.

Among those who refuse to forget are two historians from the new generation, Dave Roediger and Franklin Rosemont. For the centennial of the events they have edited this magnificent album with documents, testimonies, historical analysis and a large number of contemporary images and prints.

The publisher of the book is the Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, the first large socialist publishing house in America, which celebrated its hundredth anniversary last year.

Let us briefly recall the facts. On May 1, 1886, a great demonstration for the eight hour workday took place in Chicago, organized by the Central Labor Union. On May 3 the police shot and killed four striking workers of the McCormick factory.

On May 4, a protest meeting took place at Haymarket. The meeting proceeded peacefully, with the mayor himself in attendance. At the end of the rally-shortly after the mayor left-the police tried to disperse the crowd. A bomb was thrown into police ranks, who answered by wildly firing on the demonstrators. There were several dead and a great number of injured on both sides.

Unable to find the bomb-thrower, the police arrested the anarcho-syndicalist leaders of the Chicago labor movement. After a shameful juridical farce, five of them were condemned to death-for their revolutionary ideas rather than for any proven participation in the bombing.

Four — Albert R. Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, George Engel — were executed on Nov. 11, 1887. The fifth, Louis Lingg, used dynamite to commit suicide in his cell. Two others, Michael Schwab and Samuel Fielden, were condemned to life imprisonment and one, Oscar Neebe, to fifteen years.

In 1889, at the founding congress of the Second International, May 1 was chosen as the international day of struggle for the eight-hour workday.

Haymarket Scrapbook is composed of three sections: a presentation of the martyrs and their movement; the campaign in their defense and for amnesty (posthumously granted by Governor Altgeld in 1893); their heritage in the American and international labor movement.

Among all the documents in this collection, the most impressive ones are the speeches, proclamations and articles of the five martyrs. One is astonished not only by their courage-“I demand either liberty or death. I renounce any kind of mercy.”(George Engel) — but also by their revolutionary integrity and political insight. “I believe that everybody who has studied the true character of the capitalistic form of society, and who will not deceive himself, will agree with me that now and never will the ruling classes abandon their privileges peaceably.” (Adolph Fischer)

As anarcho-syndicalists, they did not trust isolated exemplary actions, but workers’ self-organization and the building of labor unions that are to be “a school of true civilization and a wedge driven in to the body of the present infamous system of society.” (Albert Parsons)

Their revolutionary organization, the International Working People’s Association (IWPA)-the American section of the First International-had as its outspoken aim the abolition of capitalism. Its doc trine freely combined ideas from Marx (mainly his analysis of exploitation), Bakunin and the French Revolution.

While some of the IWPA leaders, like Johann Most, isolated themselves from the real labor movement in a sectarian way, the leaders and activists of the IWPA in Chicago organized mass labor unions and led the struggle for the eight-hour workday.

One moment before being hanged, August Spies made a last declaration, which is inscribed at the monument to the martyrs of Chicago at the Waldheim cemetery: “The time will come when our silence will be will be more powerful than the voices you are throttling today.”

Remembering the Chicago Anarchists

Indeed, a new generation of militants came to the revolutionary movement under the impact of the events in Chicago: people like Emma Goldman, the leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and some of the founders of the Communist Party. James P. Cannon — a founding member of both the Communist and Trotskyist movements — himself belonged to the IWW and in a testimony published in this book recalls that Albert Parsons has always been his favorite character in American labor history.

But the influence of the Chicago martyrs was worldwide. Its echo can be found in the writings of the Cuban Jose Marti and of the Chinese novelist Ba-Jin, of the English revolutionary socialist William Morris and of the Spanish anarchist intellectual Ricardo Mella. As a matter of fact, for a century Parsons, Engel, Fischer, Spies and Lingg became the symbol of the workers’ international unity.

Writers, poets and artists were also moved by the drama of Chicago; several poems, articles and drawings included in this book bear witness to their feelings of solidarity with the five revolutionaries. In a remarkable essay on the legend of Louis Lingg, Franklin Rosemont recalls the fascination with anarchism in the cultural avant-garde movements, from Symbolism to Dadaism and Surrealism. In fact each time that a social movement rises against the bourgeois order in the United States, it rediscovers the memory of the Chicago martyrs.

Among the women active in the IWPA were Lucy Parsons and Lizzie Holmes, assistant editor of the association’s periodical, The Alarm. In an 1899 article honoring her friends, victims of a murderous class justice, Holmes wrote:

“The world worships its successful fighters and questions little why they fought. The slain and the vanquished are reviled rebels, though their cause was the noblest …. Our comrades are as yet among the vanquished: it depends on us to rescue their names from obloquy [disgrace], and to keep bright the cause for which they died.”

January-April 1988, ATC 12-13