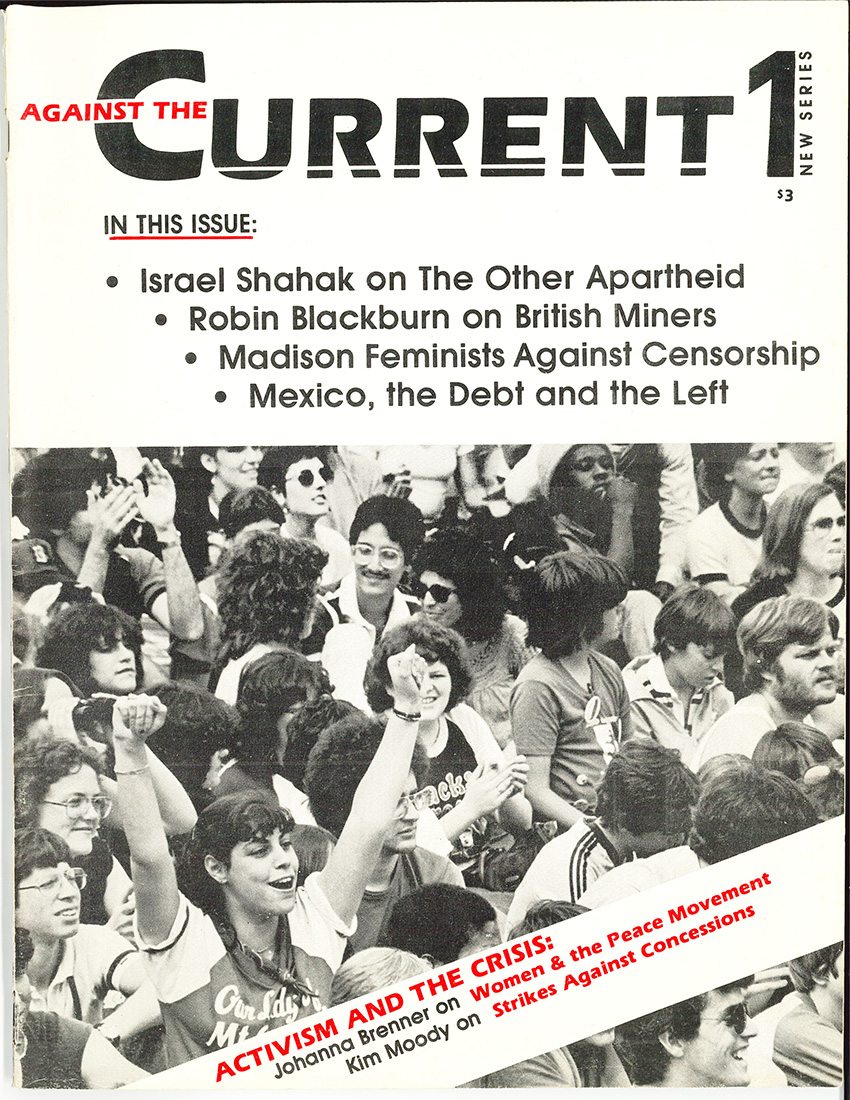

Against the Current, No. 1, January/February 1986

-

A Letter from the Editors

— The editors -

Israel Today: The Other Apartheid

— Israel Shahak - The Murder of Mahmoud al-Mughrabi

-

Thoughts on Women & the Peace Movement

— Johanna Brenner -

Random Shots: The Pope's Middle East Program

— R.F. Kampfer - Contours of the Crisis

-

Mexico: The Crisis & the Left

— interview with Ricardo Pascoe -

Miners' Strike Still Echoes in Britain

— Robin Blackburn -

U.S. Labor: Is the Tide of Concessions Finally Turing?

— Kim Moody - Feminists' Campaign Poses Alternatives

-

Porn Censors Lose in Madison

— Lynn Hannen & Daniel Grossberg -

Feminists Propose Alternatives to Pornography Free Zone (page 1 of 2)

— Mary Lauby, Leslie J. Regan & Daniel Grossberg -

Feminists Propose Alternatives to Pornography Free Zone (page 2 of 2)

— Mary Lauby, Leslie J. Regan & Daniel Grossberg -

Women's History raises doubt about value of porn law

— Kathleen Brown, Daniel Grossberg & Leslie Reagan - Dialogue

-

Notes on Gay Sexuality & Human Natures

— Scott Tucker - Review

-

South Africa's Dawning Revolution

— David Finkel - Letters

-

Remembering Steve Zeluck

— Barbara Zeluck

Lynn Hannen & Daniel Grossberg

MADISON — A “civil rights” antipornography ordinance proposed for Dane County was defeated without ever being formally drafted, circulated, or introduced.

Supporters of the would-be ordinance have since mounted a campaign to have University of Wisconsin administrators censor films on campus; they have mounted a campaign in the community for “porn free zones-safe for women and children” at area business; and they continue their other activities based on the exact language and theory underlying the ordinance.

We in Madison, in Feminists Against Repression and in the Feminist AntiCensorship Taskforce, continue to oppose the theory and practice of these campaigns, but have not limited our focus to responding to them.

Madison’s case is important in showing the directions the anti-pornography censorship/repression approach can follow, as well as that of groups opposed to this approach.

The “civil rights” innovation to censor pornography arrived in Madison in the Spring of 1984, shortly after the Mackinnon/Dworkin initiative was passed and then vetoed in Minneapolis. Promoted by the now defunct monthly paper, The Feminist Connection, the ordinance was to be drafted by the Taskforce on Prostitution and Pornography (TOPP) and introduced to the Dane County Board by Supervisor Kathleen Nichols.

In the Fall of 1984 it seemed that everyone, certainly all feminists, supported the ordinance. The Feminist Connection and others presented the ordinance as the feminist approach. The ordinance had received a great deal of local and national publicity.

A high-priced symposium on pornography (with Mackinnon and Dworkin as keynote speakers) was well attended in September. The Take Back the Night rally focused on the violence of pornography, rather than the issues of rape and self-defense. TOPP was also highly visible, organizing on a week to week basis.

Despite all of this, the ordinance faltered. Once feminists publicly questioned the wisdom of the ordinance, a debate was opened which burst the bubble of artificial consensus. TOPP had been able to sway elements of the left in Madison, particularly on campus, by implying that it spoke for the sizable feminist community here.

After the pornography symposium in September, an informal discussion was sponsored by The Collective for Socialist and Feminist Alternatives. About thirty people, mostly women, a tended and were able to express a variety of viewpoints — something that was not encouraged at the symposium. Representatives of TOPP participated in the discussion. The organization Feminists Against Repression was later formed by a number of those who attended this discussion.

Soon another group of activists, organized by Lynn Hannen from her position as a Dane County Supervisor, began to meet as a result of their concern that feminist opposition to the ordinance had not been articulated.

This group included a State Legislator, an ACLU attorney, and several social workers. They developed an issue paper, adopted the name Feminist AntiCensorship Taskforce (FACT) — at the time unaware of New York FACT — and called a press conference in midNovember. With the endorsement of over twenty local politicians and feminist leaders, FACT presented a feminist position against the ordinance and its threat to civil liberties, and called for increased debate of the issue.

Shortly after the press conference, the evening newspaper polled all 41 County Supervisors and discovered that the ordinance idea had the support of only two supervisors. After receiving media and community attention for months, the Dane County version was still unwritten. Supervisor Nichols subsequently announced that she would wait to introduce her anti-porn ordinance until after the Indianapolis version was upheld by the courts. In the end, when the ruling against Indianapolis was announced recently, she abandoned the project.

Posing Feminist Alternatives

In the meantime, within days of the FACT press conference, a debate on the ordinance was scheduled to occur between Nichols and a “libertarian feminist” from the West Coast associated with the Libertarian Party. (Perhaps due to the unveiling of feminist opposition to the ordinance by FACT, Nichols cancelled her appearance at the last minute. The proordinance position was presented by a leader of TOPP instead.)

Some of the members of the Collective, and some of the women who had attended the earlier discussion, saw in this debate a false counter-position of the “feminist viewpoints.”

They expected that the libertarian would defend the 1st Amendment and argue, in the abstract, that women chose to work in the porn industry according to the free market ideal (and she did argue this). With the well-founded expectation that the libertarian approach would push more feminists towards support of the ordinance, this group of activists developed a response to present from the floor at the debate.

The group wrote a leaflet that put forward a critique of pornography within the broader context of sexism, addressed the legitimate concern and anger over violence against women, and emphasized the danger of the ordinance to feminist, gay, and lesbian publications, artwork, and bookstores-the danger of its use as a weapon by the right and as interpreted by judges none too friendly to women. In addition the leaflet outlined a positive strategy to combat sexism and violence against women.

The development and then distribution of the leaflet at the debate was the basis of bringing together campus and community feminist activists to form Feminists Against Repression (FAR). To our knowledge FAR has been the only group formed in response to the pornography issue to develop and take up a positive social program of women’s liberation-from support informational pickets and education against sexist depictions of women, to support of reproductive rights, the equitable valuation of working women, unionization, 24 hour childcare, sex education, self-defense, lesbian and gay rights, to defending the right of women to define their own sexuality.

FAR took a more activist approach than FACT. FAR worked on a forum with the University of Wisconsin Radical History Caucus, Entitled “The Pornography Issue in Context,” and held in February of 1985, it drew 500 people. It featured historians Linda Gordon, author of Women’s Body, Women’s Right; Ellen DuBois, best known for her work on the 19th century women’s suffrage movement; and psychology professor Ed Donnerstein (whose research on the effects of pornography is often used and misused by proponents of anti-porn and obscenity legislation).

In late March, FAR brought Varda Burstyn, renowned Canadian feminist film critic, an important contributor to Marxist-feminist theory of the State and anti-censorship activist, to Madison for a weekend of lectures and interviews with the press and radio. The largest event, Burstyn’s talk on the sexual representation of women in the media (drawing, again, over 500 people) was endorsed by a number of gay and lesbian organizations, left and women’s groups, and the local feminist bookstore.

Women against Censorship (1985), a collection of essays edited by Varda Burstyn, includes her essay on alternative approaches to the pornography issue. It has been an invaluable aid to us, along with her other works published in the Canadian feminist press, in developing our own approach to the issue.

Also in March, FAR and FACT members succeeded in convincing the University of Wisconsin Teaching Assistants Association, Local 3220 of the AFT, to defeat endorsement of a campuswide petition drive organized by TOPP against pornographic films. This was a critical endorsement for TOPP, which when lost, took the momentum out of this effort.

FAR members’ attendance at various TOPP events and participation in their discussions, from time to time throughout the year, must also have had a dampening effect. This is demonstrated by the fact that TOPP would declare the ordinance out of bounds of their discussion if they knew FAR members were present.

Since the spring of 1985, FACT and FAR have been meeting and working together. OUT!, the state’s lesbian and gay newspaper, has just published our response (also reprinted here) to TOPP’s call for support of their “Pornography Free Zones” campaign.

However, the feminist agenda of FAR and FACT goes beyond responding to anti-porn initiatives. We have supported and will continue actively to support Alternative Families Legislation and Pay Equity provisions in Madison’s Affirmative Action policies. We have opposed the censorship of ads for abortion clinics (attempted here late last summer), and supported restoring Medicaid funding of abortions.

We have taken up the issue of censorship of Safe Sex/AIDS information, and we participated in Reproductive Rights Awareness Week activities in October. We will continue to support access to alternative images, literature, and films which depict female and male sexuality positively, which are made for women’s pleasure and which are not exploitative.

We have also worked with TOPP in a broader coalition to protest the assault of a woman protestor at a local adult bookstore. Our participation in the protest was important in changing the focus of the protest away from an analysis that pornography caused the attack, to a clearer position that violence to protect property is unacceptable. We emphasized that the right to protest is paramount, and that prosecution of her assailant for assault and battery be the principal demand.

Although there is disagreement within the feminist community about the effects of pornography and solutions to the problem of violence, feminists share the common goal of a just, humane, egalitarian and non-oppressive society. FAR and FACT in Madison have presented neither a program that identifies economic, social, and cultural factors-not simply, nor primarily their reflection in pornography, which maintains sexism in society. Despite the difficulty the porn ordinance has presented, we have a positive agenda to pursue our work in our community.

January-February 1985, ATC 1