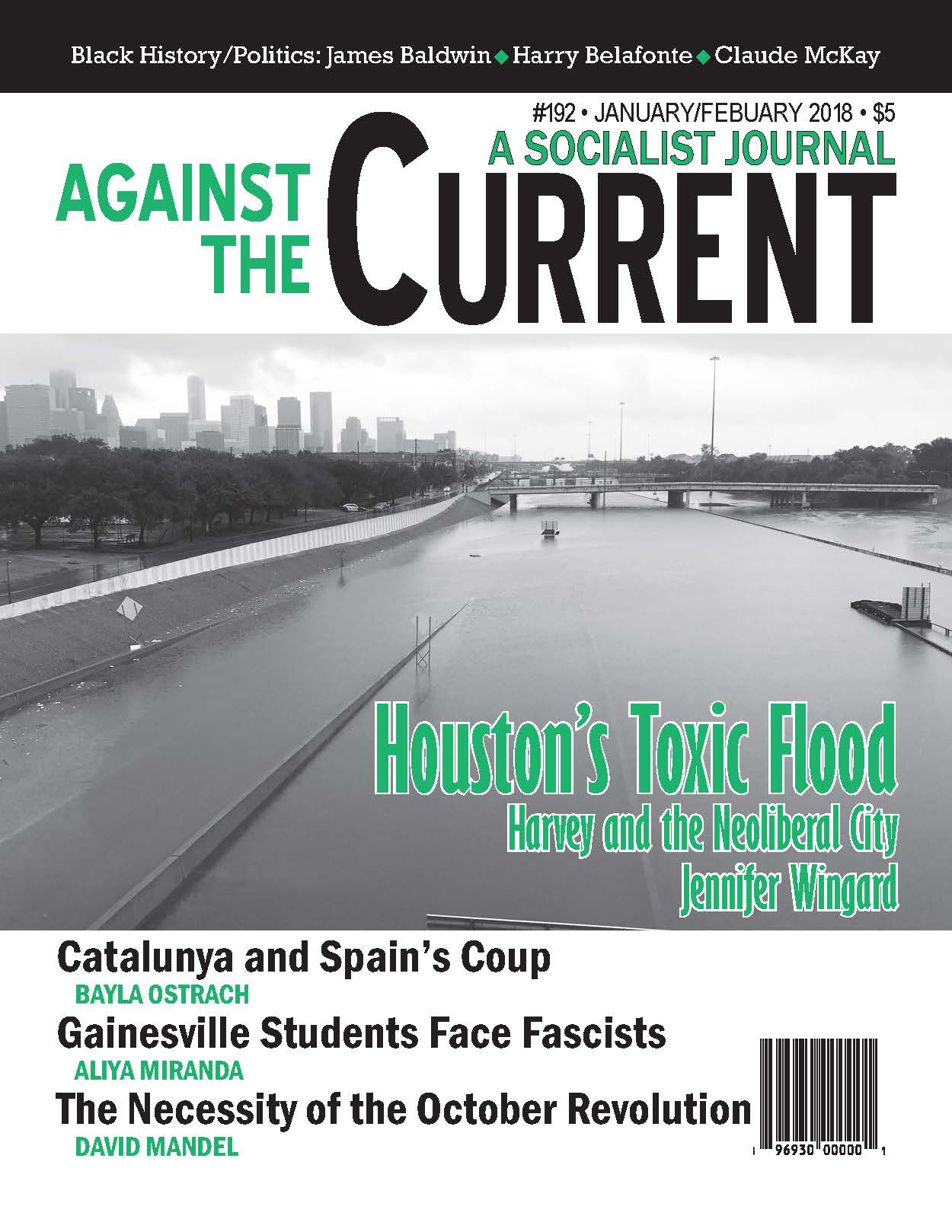

Against the Current, No. 192, January/February 2018

-

Open and Hidden Horrors

— The Editors -

The #MeToo Revolution

— The Editors -

Black Nationalism, Black Solidarity

— Malik Miah -

Harvey's Toxic Aftermath in Houston

— Jennifer Wingard -

Florida Students Confront Spencer

— Aliya Miranda -

How the UAW Can Make It Right

— Asar Amen-Ra -

The Kurdish Crisis in Iraq and Syria

— Joseph Daher -

Kurds at a Glance

— Joseph Daher -

Clarion Alley Confronts a Lack of Concern

— Dawn Starin -

Catalunya: "Only the People Save the People"

— Bayla Ostrach -

Catalunya: Organizations at a Glance

— Bayla Ostrach -

Catalunya: Abbreviated Timeline

— Bayla Ostrach - Egyptian Activists Jailed

- On the 100th Anniversary of the Russian Revolution

-

The October Revolution: Its Necessity & Meaning

— David Mandel -

Theorizing the Soviet Bureaucracy

— Kevin Murphy - Reviewing Black History & Politics

-

Race and the Logic of Capital

— Alan Wald - Black History and Today's Struggle

-

Racial Terror & Totalitarianism

— Mary Helen Washington -

Portrait of an Icon

— Brad Duncan -

Lessons from James Baldwin

— John Woodford -

New Orleans' History of Struggle

— Derrick Morrison -

Claude McKay's Lost Novel

— Ted McTaggart - Reviews

-

Language for Resisting Oppression

— Robert K. Beshara - In Memoriam

-

Estar Baur (1920-2017)

— Dianne Feeley -

William ("Bill") Pelz

— Patrick M. Quinn and Eric Schuster

Aliya Miranda

ON THURSDAY OCTOBER 19th, I sat shotgun to my dad in a minivan filled with my co-workers and interns from UF’s Samuel Proctor Oral History Program.

On any other Thursday, we would have been in the SPOHP office promoting events, archiving interviews, and working on digital production projects, and my dad would have been at work. Instead, we’d organized to carpool from Ben Hill Griffin Stadium to a Winn Dixie parking lot, maneuvering around blockades and rereading detailed safety instructions, to document the No Nazis at UF Protest against Richard Spencer.

This was the situation we found ourselves in after the University of Florida agreed to receive the Alt-Right lobbying group the National Policy Institute upon their request to rent out the Phillips Center.

Having been haunted by images of protesters outnumbered and surrounded by chanting, torch-wielding white supremacists in Charlottesville — images that resembled a scene before a lynching — we all knew where we’d be when we learned Richard Spencer was coming to our university.

The plan was to meet and conduct interviews with the protesters, march with them on foot to the Phillips Center and document reflections of the day outside the event.

From the Winn Dixie, we could already see the blockade. Police enveloped the intersection of 34th and 20th, and for what seemed like the first time, Gainesville’s usually sluggish six-lane 34th Street was empty, save for a horde of armed police officers in riot gear.

It wasn’t a part of Gainesville I recognized anymore. I began to wonder if this blockade could stop a speeding car.

Charlottesville is a college town much like my own, surrounded by a sea of rural right-wing areas that proudly wave the Confederate flag. Though many would deny it, the University of Florida is one of the strongest bastions of a Confederate history in Gainesville, still felt by both students and faculty of color on its campus.

Since the election, we had experienced a slew of racist incidents, from the uprooting of the sign our African-American and Jewish Studies building to a neonazi demonstrating in our campus courtyard, to the harassment of a faculty member of color in her office by a white supremacist — just to name a few.

After a hard-fought decision to finally dismantle the Confederate soldier statue, affectionately called, “Ol’ Joe,” from the City Hall lawn this summer, a “unite the right” rally in Gainesville seemed like the straw that would break the camel’s back.

When the news spread that Richard Spencer was coming to speak at UF, dark internet forums began to feature statements calling Florida “the next battlefield,” posted by users claiming to live on and near campus.

Despite this threat of violence, when threatened with a lawsuit by the NPI the university conceded, insisting it would do everything in its power to prevent another tragedy.

Protecting Whom?

I learned three things while documenting the events of October 19th. The first is that the over half a million dollars spent on security for this event was not spent to protect protesters as UF claimed. It was used to deter them, by constraining protest efforts, and protecting those who hoped to incite violence.

This first became evident in the prohibited items list (http://www.police.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Richard-Spencer-Speaking-Engagement-Prohibited-Items-List.pdf) put out by the University of Florida Police Department weeks before the protest.

Once we reached the parking lot, we shoved batteries, phones and IDs in our pockets and carried everything else — ecorders, microphones, headphones, photo cameras and video cameras — in hand. All bags, purses, clutches, water bottles, perhaps even our equipment, fell under the prohibited items list. The rest had to stay in the van, and my dad parked off-site where he wouldn’t get towed.

Also on the prohibited items list were signs made of anything but paper, cloth, foam-core or cardboard; signs on sticks of any kind were specifically banned. The list is overwhelmingly extensive and ends with, “Any other items that campus police determine pose a risk to safety or a disruption of classes or vehicular or pedestrian traffic.”

You can then imagine my frustration when I was told to turn back at a checkpoint for carrying a microphone. Or when I was stopped again at a second checkpoint for wearing a jacket. Or when Guerilla Medics were stopped for carrying bandages and gauze.

But what was just as frustrating to me is how easily we breezed through these checkpoints. There was no system in place to actually check protesters for these prohibited items beyond what they could clearly see upon first glance.

This wasn’t about keeping us safe. It was all theater. There was nothing dangerous about my jacket or my microphone or first aid equipment. But there was clearly something very wrong with our being there to protest. The lengths we had to go through to coordinate rides and even get to this part of campus was all intended to disrupt any plans to organize.

If law enforcement’s objective was to keep students safe, that objective was muddied completely when they confronted one of our interns in line for the Richard Spencer event because his crutches were “prohibited items.” He explained to the officer that he couldn’t walk without them, but police summarily picked him up and carried him away.

Safeguarding this event took precendence over this student’s right to attend it. His freedom of speech was suppressed because of something he had no control over. Our safety and certainly our First Amendment rights were of no concern to law enforcement that day.

The Importance of Protest

The second thing I learned was how crucial it was that we all showed up, despite the university’s and law enforcement’s every attempt to keep us away.

Rather than using its wealth to fight the National Policy Institute in court, to defend its students of color, to combat the emboldening of racists in Gainesville and to prevent Spencer from having an academic platform to promote the inherently violent concept of ethnic cleansing, the university chose to spend over half a million dollars on security and begged students not to protest.

University President Fuchs wrote the following statement in an email to UF students and faculty a week before the event:

“(Do) not provide Mr. Spencer and his followers the spotlight they are seeking. They are intending to attract crowds and provoke a reaction in order to draw the media. By shunning him and his followers we will block his attempt for further visibility.”

In the weeks leading up to the event the university president repeated ad nauseam how disturbed he was by Spencer’s ideas, and how important it was for everyone to understand that Spencer was not invited.

Still, he would then remind us all of our responsibility as a public institution to provide a safe platform for all ideas, and in the same breath insist that students not show up to the event to protest — as if Spencer did not already have an eager audience.

On the day of the event, however, despite his pledging, students did show up to protest, and so did many others in the Gainesville community and beyond. And the media did come — not because the protesters came in droves, approximately 2500 strong, but because they’ll follow any white supremacist given a large enough soapbox.

But instead of reporting about the NPI’s success in taking advantage of another university or about another tragedy sparked by their hateful rhetoric, the mainstream media reported how students rallied together and successfully shouted down Richard Spencer, leaving him disoriented and exposed for the ludicrous and vile ideas he stands for.

This was only possible because people refused to stay home or be deterred by roadblocks or checkpoints or hundreds of armed police officers.

Yet for all the university claimed to do, and even congratulated itself for doing — ensuring safety while upholding its commitment to free speech — the day did not go without violence.

At 5:20 p.m. a white supremacist, leaving the Richard Spencer event in a car with two others on Archer Road, shot at a group of protesters walking back to their cars. The three men were from Texas and stopped beside the group of protesters prior to the shooting to chant and cheer Adolf Hitler. They were arrested four hours later.

Six hundred thousand dollars’ worth of law enforcement did not stop this attempted murder that took place in my town. If Spencer had not come to speak on campus, these men would not have been here in the first place.

The Alt-Right, who continue to defend the murder of Heather Heyer, incite violence wherever they go. There is nothing peaceful about their objective.

This is the third thing I learned on October 19th: when you accept ethnic cleansing as a topic of academic debate, violence is inevitable.

The university knew what kind of violence is sparked by the Alt-Right, and they opened their doors to them anyway. Beyond that point, there was nothing they could have done to prevent this incident.

I only hope that what the people of Gainesville did when forced into this situation serves as an example to every other town targeted by these sorts of groups. Strength in numbers has never rung more true than in times like these.

Had protesters not arrived in swarms the way they had, more of these white-nationalist terrorists would have filled the auditorium and would have unabashedly reaped even more havoc afterwards.

At UF, when the safety of protesters is threatened by Nazis, the administration’s answer is to keep the protesters from protesting. I implore every other institution to resist normalizing this standard.

January-February 2018, ATC 192