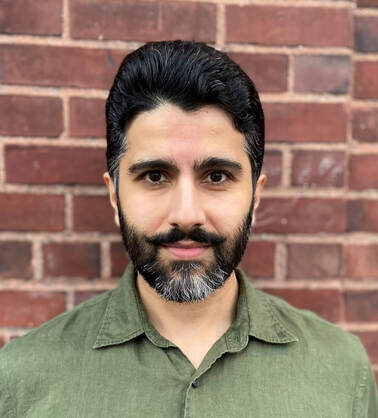

Sara Abraham interviews Navyug Gill

Sara Abraham: You’re a historian of Punjab so I would like to ask you about the historical depth of this struggle. It came from a deeper place than just reacting to Modi.

Navyug Gill: I would reframe that in this sense: of course, the farmers were fighting the Modi government, but the neoliberal agenda has a bipartisan consensus among most major parties in India. The Congress Party is fully on board with this project.

The fact that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) enacted these laws gave Congress a veneer of saying they oppose them, but they would no doubt impose something similar if given the chance. Indeed, they’re the party that privatized the economy in the early ’90s, and their statements repeat the same neoliberal euphemisms of “competitiveness,” “reform” and “private investment.” Despite the cries of liberal commentators, Congress is not a meaningful alternative.

I think one way to understand the depth of this struggle, and its historical resonances, is through the tension between so-called center and periphery. In Panjab there is a longstanding history of antagonism towards the spectre of Delhi. Not only is Delhi the national capital since 1947, but it was a major administrative center under British rule, and earlier the seat of power of the Mughal empire.

Popular Resistance

A major theme in Panjabi popular imagination is contending with the authority of Delhi, to resist subordination and assert autonomy. This has taken quite diverse manifestations: from the anticolonial Ghadar Party in the early 20th century and Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s independent kingdom circa 1799-1849, to the struggles led by Banda Singh Bahadur and the Sikh misls in the 18th century and the revolt by Dulla Bhatti against Emperor Akbar in the 1500s.

Each instance can be creatively invoked to demonstrate how this region has not readily accepted being made periphery to an assumed center. Today this is evident in the songs, poetry and everyday idioms that emerged through this struggle. The term Dilli Sarkar or Dilliye captures both menace and mockery in Panjabi, as the government’s authority is presented as arbitrary as well as enfeebled. A recent example is Jas Bajwa’s protest song “Dekh Dilliye” but the most evocative expression would be the poem “Dilliey Deiala Dekh” by Sant Ram Udasi from the 1970s.

I think that the bravery to confront one’s adversary and fight injustice resonates strongly on that popular level. While at present the Dilli Sarkar is the BJP, it is also the Congress, or any other party that attempts to dictate Panjab’s future from a distance.

SA: Does anything about that history then point to what needs to be decolonized now? Is the history useful to understand what was wrong with what was done, and which continues to impact the present?

NG: I think the most obvious thing is this so-called federal structure of India. On the one hand, these laws in effect are a violation of the Indian constitution – for those who still believe in it. Agriculture is supposed to be under state jurisdiction, yet the central government was intent on deregulating and privatizing a system of procurement and distribution that was in place for the last 50 years.

Recall that Panjab is just 2% of the territory of India, but generated upwards of 70 to 80% of the wheat and rice that fed the country for five decades. This was key to preventing famine and making India food self-sufficient.

All of a sudden, however, the central government decreed the dismantling of this system, which would potentially throw millions of people into the nightmare of the market and destabilize the entire economy.

On the other hand, “decolonization” could go even further, to question what gives Delhi the right to manipulate and imperil the fate of a region in the first place? Democracy and sovereignty have long had an uncomfortable dissonance in the subcontinent.

SA: It would not have been any better if the state government, the Punjab government had passed the same laws?

NG: That is extremely difficult to imagine. I think the key difference is that a state government in Punjab would have no constituency advocating the passing of these laws. Whom would they be trying to empower or promote?

Whatever might have been gained by enriching a few corporate interests would be offset by massive rural volatility and impoverishment. Popular opposition would make it impossible for any state government to do such a thing.

As a counter-example, it’s worth recalling that in 2004, Capt Amarinder Singh, as the Congress Chief Minister in Panjab, unilaterally canceled the Sutlej-Yamuna Link Canal. This was the centerpiece of the central government’s plan to divert Punjab’s waters to Haryana. He canceled it as a sitting Congress chief minister, arguing that it was unequivocally to the detriment of the state. His move caused a huge divide within the national Congress Party, but his standing grew significantly in Panjab.

The point is that neither the Congress, nor the Akalis or even AAP (the Aam Admi Party) could have passed state laws that would privatize agriculture in one fell swoop. Perhaps they might attempt to do so piecemeal in the future. Still, such neoliberal callousness could only be enacted by a Delhi-based central government driven by the calculations of an all-India framework without regard for the consequences to Punjab.

Meaningful Solidarity

SA: You mentioned all-India a couple of times. How broad was the reach of the impact to the farmer’s movement in other parts of India?

NG: Back in January 2021, I remember having conversations with friends about the involvement of other states in India. There was a feeling that, if these states are interested in challenging the dominance of Delhi and the neoliberal agenda, and if they really want a new agrarian model, then there are still a few open roads to Delhi that could be shut down.

Let the farmer unions in Maharashtra or Karnataka or West Bengal march on the capital and block those routes to increase pressure on the government. That would be a way not only to engage in sympathy for Punjab and Haryana, but to bring about a genuine transformation across the country.

Maybe this was wishful thinking at the time, especially because unions in those states are not as well organized or influential – but history has accelerated the underlying point.

In terms of impact, I think there are at least two sides to it. One is that there was absolutely meaningful solidarity from the rest of the country. Delegations of farmers came from places like Bihar, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, spent time at the various protest sites, and then returned to their home states. They were coordinating with the leadership of the SKM from early on in the struggle.

Second, there were various kinds of public protests across India, in places like Bombay and Bangalore and Madras as well as smaller cities and towns. People in Delhi overwhelmingly supported their avowed besiegers, as many urban poor on the outskirts received two meals a day at the Sikh langars operating at the protest sites.

They expressed deep affection toward the farmers, and were greatly saddened when they ultimately departed. This might even be unprecedented in the history of protest – that local people did not want it to end.

From this perspective, the struggle took on a sort of all-India quality in the sense that most everyday people could see that what was being done to farmers was unjust. I also think the question of food production resonated at a primordial level – the very people who grow the food you eat are being exploited and rendered precarious solely for the benefit of giant corporations.

Now what has happened is that an all-India MSP [minimum support purchasing price for specified crops] has been made central to the demands, which I think is actually quite radical because this now directly affects farmers everywhere.

Anybody engaged in agriculture can see the power of having an MSP along with the requisite purchasing infrastructure knowns as mandis [government procurement markets]. Moreover, the example of Bihar in 2005 is well-known: the state dismantling of mandis was a disaster, especially for small and marginal farmers.

Thus, if a comprehensive MSP + mandi system gets enacted, it will not only ensure the wellbeing of cultivators across the country but also be the most severe setback to the global neoliberal agenda. There is real potential for other states to join the struggle because the possibilities are tremendous.

SA: Do you know there is, or do you think there should be, such a pan-India development?

NG: We live and die on hope. I think such a development is in the works because that is what the SKM is gearing up to discuss at its January 15th meeting. Kisan unions in all these other states are busy mobilizing in anticipation because if it seems the government will backtrack on its pledge; then the burden to escalate will grow on everybody.

Indeed, the fact that this government has been forced to concede on the farm laws has buoyed everyone’s expectations.

It might be worth reflecting on the peculiar way we talk about states’ rights in America versus in India. States’ rights in America have usually been used as a means to ensure white supremacy and racist segregation, and to prevent the government from enacting any egalitarian measure, from universal healthcare to gun restrictions and abortion access. States’ rights are the enabling cover for right-wing politics.

In India, however, states’ rights are something entirely different. I think it’s the genealogy of these different states and the notion of what is India and how it imposed its rule that is crucial.

Remember this country is 74 years old; I know people who are older than this country called India. The many states in India actually have different interests: They have different ecologies; they have different cultures and histories which cannot simply be contorted together to fit this model.

Moving Forward

SA: Yet there is also a lot to learn from the United States in terms of increasing state capacity to do what the local states in India could be doing but not doing, in the face of the center. They keep surrendering on environmental legislation, for instance, whereas they could be enacting far more progressive legislation at the state level.

I want to move on. What changed in your life in the last year? By that, I mean what changed in the world of not just Punjabis, but progressive Indians outside India? Are there new networks, are there new organizations, is there a new focus to the left political diaspora of India? Are there new meetings, gatherings, networks? Has there been coordination on the intellectual front?

NG: That’s an interesting question. I think the organizing that has emerged and the connections that have been forged are hopeful signs. Friends, colleagues and strangers have interacted and connected to this struggle in a variety of ways.

It’s happened not only with the Indian diaspora, but also the wider subcontinent from Pakistan and Bangladesh, and their descendants settled in the West, along with various strands of progressives and radicals from elsewhere. My comrades from Egypt and Mexico were as interested as those from Iran and Korea.

No doubt that’s been heartening. Yet in terms of concrete organizing – apart from scholarship or academic conversations – it’s been the Sikh Punjabi community that has been at the forefront of almost everything I’ve been involved in. Any of the real, sustained movement building has been community driven and taken place within existing faith networks, friendship networks or family networks, and then people have grown and connected throughout.

To some extent, this is understandable, because the struggle emerged in a specific region and initially had geographical boundaries, so it is logical that it would follow those lines in the diaspora.

Now, suspicions are raised when people who work on agrarian history, or are experts in class and caste politics, and yet have not been vocal about this struggle. But I think such quietism might go back to the elemental difference between intellectual interests and political commitments. We don’t talk enough about instincts, but they matter a great deal.

SA: It makes sense that the stage is given to Punjabis to speak, reflect and connect because that connection is very real. It’s heartfelt whether it’s for reason of having family back home or some sense of the injustice that Punjabis have faced in Delhi. Were Punjabi youth who have been born and raised abroad, the third generation, fourth generation, able to connect to this movement?

NG: Absolutely. If we just take popular culture depictions, all the nauseating machismo and materialism that was dominating the music scene for decades seemed to reach its lowest low point in the last few years.

Yet with the rise of this movement, you have the emergence of new forms of art, from poetry and short films to songs and music videos. This drew in diaspora youth who otherwise might only have a tenuous connection to Panjab. Not everyone has family in a village or goes back often.

Many might be two, three or four generations removed, and may not have not visited at all. Yet they too were able to viscerally connect to the struggle through artistic idioms of self-respect, bravery and confronting one’s adversary. These songs, then, were a welcome relief from the usual mainstream nonsense of trivial bravado.

Songs and the Struggle

SA: Tell us more about this. Where were the songs coming from?

NG: If you took the landscape of Punjabi singers, there were several who rose to the occasion and actually got involved in this struggle right from September 2020, well before the march on Delhi. They started writing songs and making videos that circulated in Panjab and India to across the world.

The key mainstream singers would be Jas Bajwa, Kanwar Grewal, Harf Cheema, Rupinder Handa, Ranjit Bawa Rajvir Jawanda, and Babbu Maan. Collectively their songs racked up tens if not hundreds of millions of views on YouTube and became the soundtrack of the protest.

Panjabi youth, born and raised in the West, who might not have ever even went to Punjab, never saw a field in their lives, don’t know what a mortar is, never sat on a tractor – they played these songs on repeat for over a year.

SA: In terms of self-pride and courage and the will to fight, did songs come out of the diaspora as well?

NG: Yes, they did. The category of “diaspora” itself is tricky, in the sense that some of these artists have been living out here and going back and forth.

For instance, Jazzy B, who’s had a long career and has made very famous pop songs as well as frivolous and ridiculous songs, I think he’s based in Vancouver now, but came out with a brilliant song called “Bagawatan” (written by Varinder Sema) meaning rebellion or uprising.

It is remarkable — every stanza of this song is brilliant, and it’s played on the streets of Vancouver and Toronto and London and New York all the time.

There are also artists who are based entirely in the West. They might not have gotten that famous, and their songs might not have elevated to that level of a Jazzy B. But if they put out their poetry and they made a song, it circulated in their own circles and online through Instagram. To have a song about this struggle became a badge of honor for Panjabi artists; to not have one will incur endless shame.

SA: One of the singers you mentioned, you said she was a woman. Rupinder Handa, what are her songs about?

NG: Her most important song about the struggle is titled “Halla Sheri” (written by Matt Sheron Wala). The chorus goes something like this: “I’ll water the wheat in the fields, you [my beloved] remain steadfast at the Delhi border.” Later in the song, she actually says “Don’t bother coming back unless you gain your rights,” Implying death would be preferable to defeat.

In the video she’s in a field, driving a tractor, starting a generator, and re-directing a water course using a hoe. It’s one of the most unique songs I’ve ever heard, especially because of how it appropriates and refracts the masculine idioms of farming for a woman – not only giving encouragement but claiming the power to cultivate in her own right.

SA: Was the SKM leadership able to acknowledge how important the intellectual side of things was along with the cultural?

NG: Yes. The SKM leadership did, but I think particularly the second and third-tier leadership knew the value of diaspora solidarity, both for protesting and mobilizing as well as the writing and speaking. Initiatives like the Trolley Times, the newspaper that was started at the front lines, or the “Tractor 2 Twitter” hashtag, enhanced the struggle beyond spatial limits.

At the same time, we should recognize that much of this activism was decentralized and self-driven, with people taking the initiative to rise to the challenge. Nobody was told what to do, nobody was paid any money. This is not like the BJP IT cells.

Of course, the organized cadre of the SKM and the Punjabi unions played a role, but there were many more people that took it upon themselves to challenge these right-wing narratives and put forward alternatives.

In this sense, the entire Western left ought to pay homage to this struggle, not least because it is the most significant defeat of neoliberalism in the 21st century. It ought to reverse the arrogant notion that creativity and progress against capital automatically originates in the West and radiates outward to the rest of the world.

Instead, Americans interested in confronting capitalism should have the humility to learn from what people in Panjab have achieved, and then perhaps try to make sense of their own society through this victory.

New Organizing

A: One of the leaders of SKM, Gurnam Singh Charuni, has launched a political party, after the phenomenal victory of the farmers’ movement in repealing the farm laws. What are your thoughts on this?

NG: The various farmer and laborer unions have different political orientations and party affiliations, and different histories. Some of them are closer to one party or another, some of them have sectional interests. They’re based, geographically in the different sub-regions of Panjab (Malwa, Majha and Doaba), but also on the crops people are growing. For instance, the sugar cane unions are different from the cotton growers versus the wheat and paddy folks.

Throughout this struggle, they’ve managed to maintain a remarkable unity. Yet there was a constant media pestering of “Are you planning to run in elections, what’s going to happen with the elections? What should you do in the elections?” Now in the last month or so, the question has come to the fore in a new way and has become unavoidable.

Charuni is a farm union leader from Haryana. He was one of the leaders of SKM, and most vocal about entering electoral politics. His argument is that these laws came about through the electoral process, and so it is necessary to engage in that process to take back power. In the last few weeks, he announced the formation of a new party – called the Sanyukt Sangharsh Party – that will field candidates in the Punjabi election scheduled for February 2022.

There is also a new group that has been formed called “Jujha Panjab,” which means something close to “Striving Panjab.” This is made up of civil society activists, filmmakers and artists, prominent economist, scholars and religious leaders.

They are not planning to contest the election, but have constituted themselves as an outside sort of pressure group, to raise questions and issues though not necessarily engaging in public protests.

Finally, there are farmer and laborer unions that have a longstanding opposition to electoral politics. Most important is the BKU (Ugrahan), as well as the Kirti Kisan Union, Krantikari Kisan Union, the BKU (Sidhupur) and the Kisan Mazdoor Sangharsh Committee.

They argue that not only is the current struggle unfinished until the governments concedes on an all-India MSP and proper compensation for the 725 martyrs [who were killed during the farmers’ struggle –ed.]. Furthermore, they hold that electoral outcomes neither adequately address peoples’ immediate needs nor provide meaningful systemic change. For them, the growth of sustained popular power – as exemplified in this victory – is the only way forward.

At this juncture, I think the critique of the notion that elections in a bourgeois, liberal framework are not much more than a way to legitimize existing power structures holds. However, after such an incredible struggle, when people have been politicized and radicalized in new ways, it might not be unreasonable to revisit this question. The status quo is actually quite fractured, with new possibilities emerging. Right now, I therefore think this is a worthy debate.

For a global audience, the larger point might be to emphasize that the nature of democracy is being re-imagined in far more creative and consequential ways than in the US. Here, it seems we are perpetually mired in a narrow, lesser-of-two-evils discourse that goes almost nowhere every four years.

Yet currently in Panjab, there is a much broader political spectrum with a variety of old and new actors and initiatives grappling with fundamental questions of what it means to make choices and live together. While there is no guarantee of the outcome, such a horizon has only become possible through immense solidarity, sacrifice and determination.

Against the Current