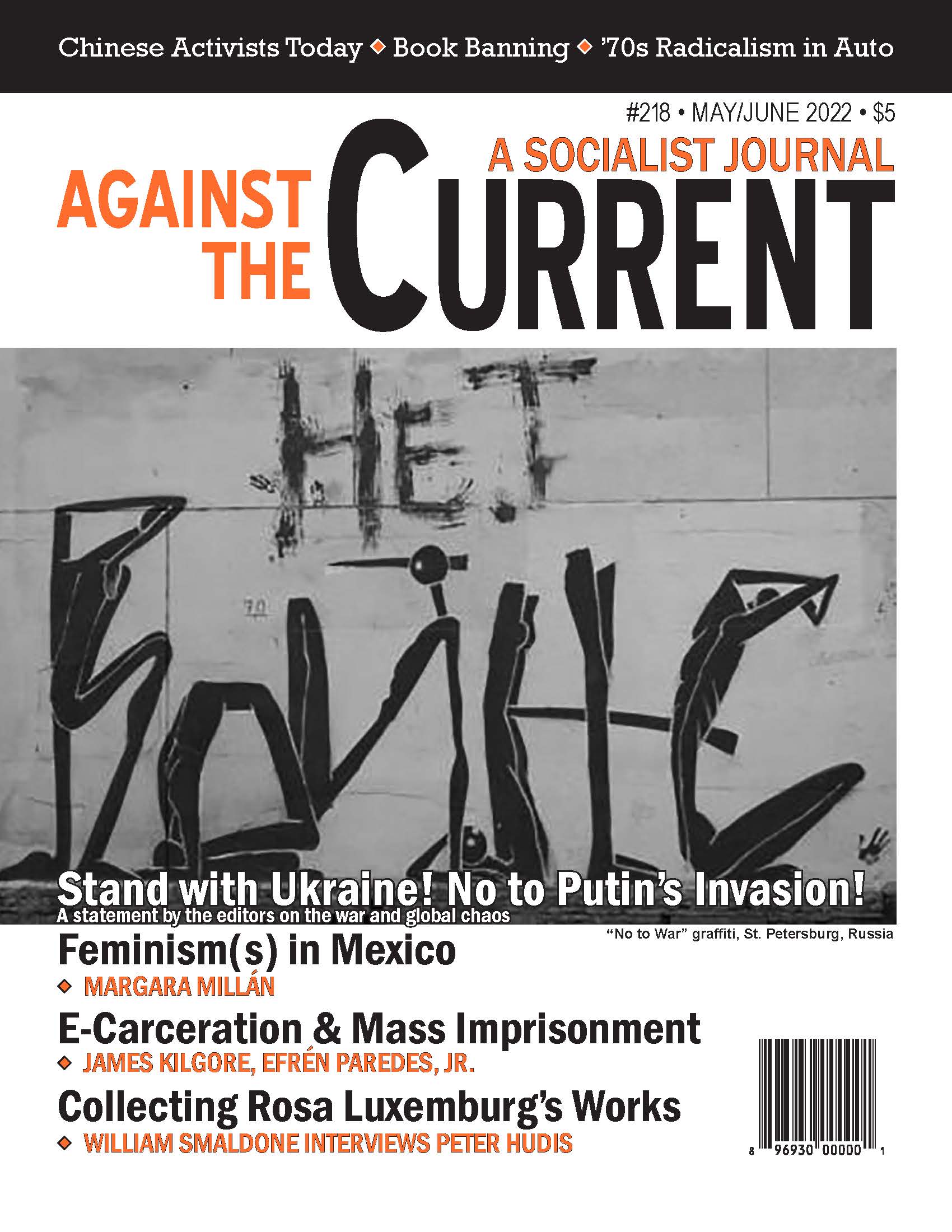

Against the Current, No. 218, May/June 2022

-

Out of the Imperial Order: Chaos

— The Editors -

"Nationtime": The Black Political Convention

— Malik Miah -

Rising Up at Amazon

— Dianne Feeley -

Book Banning Past and Present

— Harvey J. Graff -

Punishing the Criminalized Sector of the Working Class

— James Kilgore -

The Invisible Chinese Activists

— Mo Chen -

Feminism(s) in Mexico

— Margara Millán -

Faiz Ahmed Faiz: The Restless Traveler

— Ali Shehzad Zaidi -

The Complete Rosa Luxemburg

— William Smaldone interviews Peter Hudis - Revolutionary Experiences

-

Introduction to Revolutionary Experience

— The Editors -

On-the-line in Auto -- 1970s-1990

— Elly Leary -

Organizing in '70s Wisconsin

— an interview with Jon Melrod - Reviews

-

Prison Abolition: A Primer

— Efrén Paredes, Jr. -

How Alice Became an Activist

— Adam Schragin -

When Radicals Ran the U.S. Congress

— Mark Lause -

Dust Bowl Chronicler

— Cassandra Galentine -

Surveying Revolutionary Thought

— Herman Pieterson

Ali Shehzad Zaidi

THE REVOLUTIONARY URDU poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911-1984) retains its transformational power. Recently, Faiz’s “We Will See” became a rallying cry during student protests in India against the 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act which grants a path to citizenship only to non-Muslim refugees from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

The act also denies citizenship to those Indian Muslims who, lacking the means to acquire identity papers and birth certificates, are subjected to disenfranchisement, deportation, and imprisonment even if they were born in India.

Faiz wrote “We Will See” in defiance of Zia-ul-Haq’s military dictatorship (1977-88). Its title, which evokes Judgment Day, is taken from a refrain in the Qur’an (Singh):

We will see.

Certainly we, too, will see

That promised day —

That day ordained

When these colossal mountains

Of tyranny and oppression

Will explode into wisps of hay —

The day when the earth under our feet

Will quake and throb

And over the heads of despots

Swords of lightning will flash —

The day when all the idols

Will be removed from this sacred world

And we, the destitute and the despised,

Will, at last, be granted respect —

The day when crowns

Will be tossed into the air

And all the thrones utterly destroyed.

Only the name of God will remain

Who is both absent and present —

Both the seen and the seer.

The cry “I am Truth” will rend the skies

Which means you, I, and all of us.

And sovereignty will belong to the people

Which means you, I, and all of us.

(Faiz in English 24-25)

The poem deposes the idols of money, power, and prestige while seeking meaning in collective existence. The words “I am Truth” are those uttered by the Persian Sufi mystic Mansour Hallaj who was executed in the early 10th century. They affirm the unity of all creation, heightening the paradox of God existing, seemingly at once, everywhere and nowhere.

Even before the partition of India, Faiz had become a literary sensation with the publication of his first collection of poetry Naqsh-i-Faryadi (The Lamenting Image) in 1941. After Pakistan’s independence in 1947, Faiz became the chief editor of The Pakistan Times.

In 1951, Faiz came further into national prominence during the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case, in which he and many of his associates were imprisoned, blacklisted, or forced underground. Among them was Sajjad Zaheer, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP) who, like Faiz, spent four years in jail.

In 1954, while Zaheer was still imprisoned, the CPP, repressed since its inception, was banned outright. After his release from jail in 1955, Zaheer went into exile in India. In his memoir The Light, written in prison, Zaheer affirms:

“History is witness to the fact that conservative rulers and unlawful governments have always tried to put down the voice of truth with force and violence. If they have not been able to buy off or intimidate an independent mind, a truthful tongue, or a bold pen, they have used the iron chair, the poison cup, or the executioner’s sword to achieve their end. But history also proves that the free spirit of man can never be confined. No true scholar, poet, or artist, whose work reflects the evolving reality of his times, can be suppressed. Even if he is forcibly silenced, the very reality that is denied free expression bursts forth like clear springs from the hearts of millions of the common people.” (The Light 72)

Faiz was released from prison the same year as Zaheer and went into exile in London. As had been imprisonment, exile proved to be a seminal and defining experience for Faiz, as in “Resolution”:

My heart, my restless traveler:

again it has been decreed

that you and I be banished

from this our beloved land.

We will construct our poems

in foreign towns

and bear our contempt for oppressors

from door to door.

(Faiz in English 28)

Travel would remain a constant for Faiz. Late in life, Faiz wrote two memoirs of his visits to socialist countries: Cuban Travelogue (1973) and Months and Years of Friendship: Recollections (1981), which concerns his impressions of the Soviet Union.

Exile, Return and War

After co-founding the Afro-Asian Writers Movement at the 1958 conference in Tashkent, Faiz returned to Pakistan but was arrested upon arrival. He spent two years in prison and, after his sentence was commuted, again went into exile in London.

Faiz returned to Pakistan in 1964 to become the principal of Abdullah Haroon College in the working-class neighborhood of Lyari in Karachi. During his exile, the regime of General Ayub Khan had consolidated power through its Inter-Services Intelligence agency.

Ayub won the 1965 presidential election despite losing the popular vote to Fatima Jinnah, sister of Pakistan’s founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah. In a tainted indirect election, Ayub claimed victory with the support of more than 62% of the electors. Two years later, Fatima Jinnah, who had become a symbol of resistance to the military regime, died in her home under suspicious circumstances.

In 1968, the student protests that were sweeping Paris, New York, Mexico City, and other major cities, spread to Pakistan. Popular support for the demonstrations and strikes against the military dictatorship forced Ayub to resign in March 1969. Ayub was succeeded as president by the Army Chief of Staff, General Yahya Khan.

Although he allowed direct elections to be held in 1970, Yahya refused to yield power to the winner of those elections, namely, the Awami League, which had pledged autonomy for East Pakistan. In March 1971, Yahya suspended the constitution and dissolved the National Assembly, causing the leader of the Awami League, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, to call for the independence of Bangladesh.

The Pakistani Army massacred Bengali nationalists and intellectuals, including students and professors at Dhaka University. Meanwhile, Bengali mobs and the separatist guerillas known as the Mukti Bahini were massacring Biharis and other Urdu-speaking Pakistanis.

War between India and Pakistan began in December 1971, ending that month in the surrender of the Pakistani Army in East Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh. In this excerpt from “Return from Dhaka,” Faiz mourns the communal madness that had transpired:

Twisted brass bangles

and laughter

slit from ear to ear.

On every tree

a crucified nightingale.

The river reflects the sky

and the sky is the growl

of a tiger.

Will the monsoons restore

colour to the earth?

How long

will the fuel of pain

burn?

(The unicorn and the dancing girl 96)

The image of the tiger recalls the tigers that roam the Sundarbans, the mangrove forests of Bangladesh, as well as the ferocity of the cataclysmic events taking place there. The sky’s reflection in the river awakens the memory of the monsoons during the seventies that resulted in floods as well mass famine in Bangladesh in 1974.

In a speech about the classical Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib, Faiz said that the mark of a poet’s greatness is the ability to encompass the world’s pain in one’s art (Hashmi 100-101). This ability, a measure of Faiz’s own greatness, is on full display in “Return from Dhaka.”

Theme for a Poet

Through his alchemic imagination, Faiz turned pain into something beautiful and lasting, as in “Theme for a Poet.”

Imagine roses blooming

in a limestone quarry

and wine squeezed out of

desert thorns.

Mountain stream

cleaved in two

by a dark boulder.

Fear and hope.*

(Faiz in English 31)

Roses connote love, passion, and divine contemplation. The image of limestone, which has healing properties, conveys the poet’s quest to transmute suffering in the parched spiritual wilderness evoked by the desert thorns. Wine symbolizes initiation into mystical knowledge and joyous communion which can be realized even amidst desolation.

The mountain stream is an image that combines water, the source of life, with the mountain, representing spiritual ascension and stature. Although a dark boulder blocks the mountain stream’s path, water, to take the long view, will eventually find its way. The temporarily thwarted progress towards justice awakens both fear and hope.

According to the Urdu poet N. M. Rashed, Faiz was influenced by the Romantic poets, especially Keats and Shelley (8). Faiz found in the 19th-century composer Chopin a kindred romantic soul. In “Chopin’s music,” Faiz summons a bitter-sweet world of destruction and creation:

Rain-spears and the night a sieve.

Weeping walls, houses sunk in silence

And freshly-bathed plants.

Winds in the lanes and alleys.

Chopin’s music is being played.

The moon’s pallor

On the face of a wistful girl.

Blood on the snow

And every drop a leaping flame.

Chopin’s music is being played.

Lovers of freedom ambushed by

the enemy.

A few escaped.

Others were slaughtered.

They will always be remembered.

Chopin’s music is being played.

A crane covers her eyes with her wings

And weeps alone

In the sky’s blue wilderness.

A hawk pounces on her.

Chopin’s music is being played.

Grief has petrified a father’s face.

The mother sobs as she kisses

The forehead of her dead son.

Chopin’s music is being played.

The season of flowers has returned

And lovers rejoice.

Everywhere there is the dance of water.

Neither clouds nor rain.

Chopin’s music is being played.

(Faiz in English 59)

The image of rain-spears evokes tears and piercing pain. In China, the crane symbolizes longevity and its migratory flight heralds the arrival of spring besides evoking the soul’s immortality. In India, the crane is associated with treachery (Chevalier and Gheerbrant 240-241), which can be seen in the crane’s fate in “Chopin’s Music.”

The moon’s pallor recalls Percy Shelley’s “To the Moon” in which the moon is a disconsolate pilgrim of history:

Art though pale for weariness

Of climbing heaven and gazing on the earth,

Wandering companionless

Among the stars that have a different birth, —

and ever changing, like a joyless eye

That finds no object worth its constancy?

(Shelley 1081-1082)

These poignant images in “Chopin’s Music” beckon us to, if not to intervene in the world, at the very least to bear witness. To invest an unjust world with feeling is to become its heart and conscience.

Works Cited

Chevalier, Jean and Alain Gheerbrant. Dictionary of Symbols. Tr. John Buchanan-Brown. London: Penguin Books, 1996.

Dubrow, Jennifer. “Singing the Revolution” India’s Anti-CAA Protests and Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge.” Eikon.

Faiz, Faiz Ahmed. Faiz in English. Tr. Daud Kamal. Karachi: Pakistan Publishing House, 1984.

Faiz, Faiz Ahmed. The unicorn and the dancing girl. Ed. Khalid Hasan. New Delhi: Allied Publishers, 1988.

Hasan, Khalid. “Introduction.” Flower on a Grave. By Ahmed Nadeem Qasimi. Tr. Daud Kamal. Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2008: ix-x.

Hashmi, Ali Madeeh. Love and Revolution: Faiz Ahmed Faiz: The Authorized Biography. New Delhi: Rupa 2016.

Rashed. N. M. “Interview with N. M. Rashed.” Mahfil 7.1-2 (Spring – Summer 1971): 1-20.

Shelley, Percy. “To the Moon.” The Book of Georgian Verse. Ed. William Stanley Braithwaite. New York: Brentano’s, 1909: 1081-1082.

Singh, Sushant. “The story of Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge – from Pakistan to India, over 40 years.” The Indian Express (27 Dec. 2019). Web. https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/the-story-of-faizs-hum-dekhenge-from-pakistan-to-india-over-40-years-caa-protest-6186565/

Zaheer, Sajjad. The Light. Tr. Amina Azfar. Karachi: Oxford UP, 2006.

*The above text of “Theme for a Poet” is Kamal’s revision of the original version in Faiz in English. The second half of the poem formerly read:

fear and hope.

Mountain stream cleaved in two

By a dark boulder

Hunger is the wild dog.

(Faiz in English 31)

May-June 2022, ATC 218