Against the Current, No. 215, November/December 2021

-

The Rising Price of Insanity

— The Editors -

Reproductive Justice on the Line

— Dianne Feeley -

Teenagers Are Children, Not "Bad Seed"

— an interview with Deborah LaBelle -

Blocking an Ecocidal Pipeline

— an interview with Rebecca Kemble -

The Ecosocialist Imperative

— Solidarity Ecosocialist Working Group - Hitting the Bricks for "Striketober"

-

The Assault on Rashida Tlaib

— David Finkel -

Nicaragua, as Elections Approach

— Margaret Randall -

Crime Scene at the U.S.-Mexico Border

— Malik Miah - Revolutionary Tradition

-

The '60s Left Turns to Industry

— The Editors -

The SWP's 1970s Turn to Industry

— Bill Breihan -

Organizing in HERE, 1979-1991

— Warren Mar - Reviews

-

Preserving Voices and Legacies: Jazz Oral Histories

— Cliff Conner -

On COVID's Death Toll

— David Finkel -

Reflections on Party Lines, Party Lives, American Tragedy

— Paula Rabinowitz -

Reclaiming the Narrative: Immigrant Workers and Precarity

— Leila Kawar -

Envisioning a World to Win

— Matthew Garrett -

Sharing and Surveilling

— Peter Solenberger -

A Labor Warrior Enabled

— Giselle Gerolami

Dianne Feeley

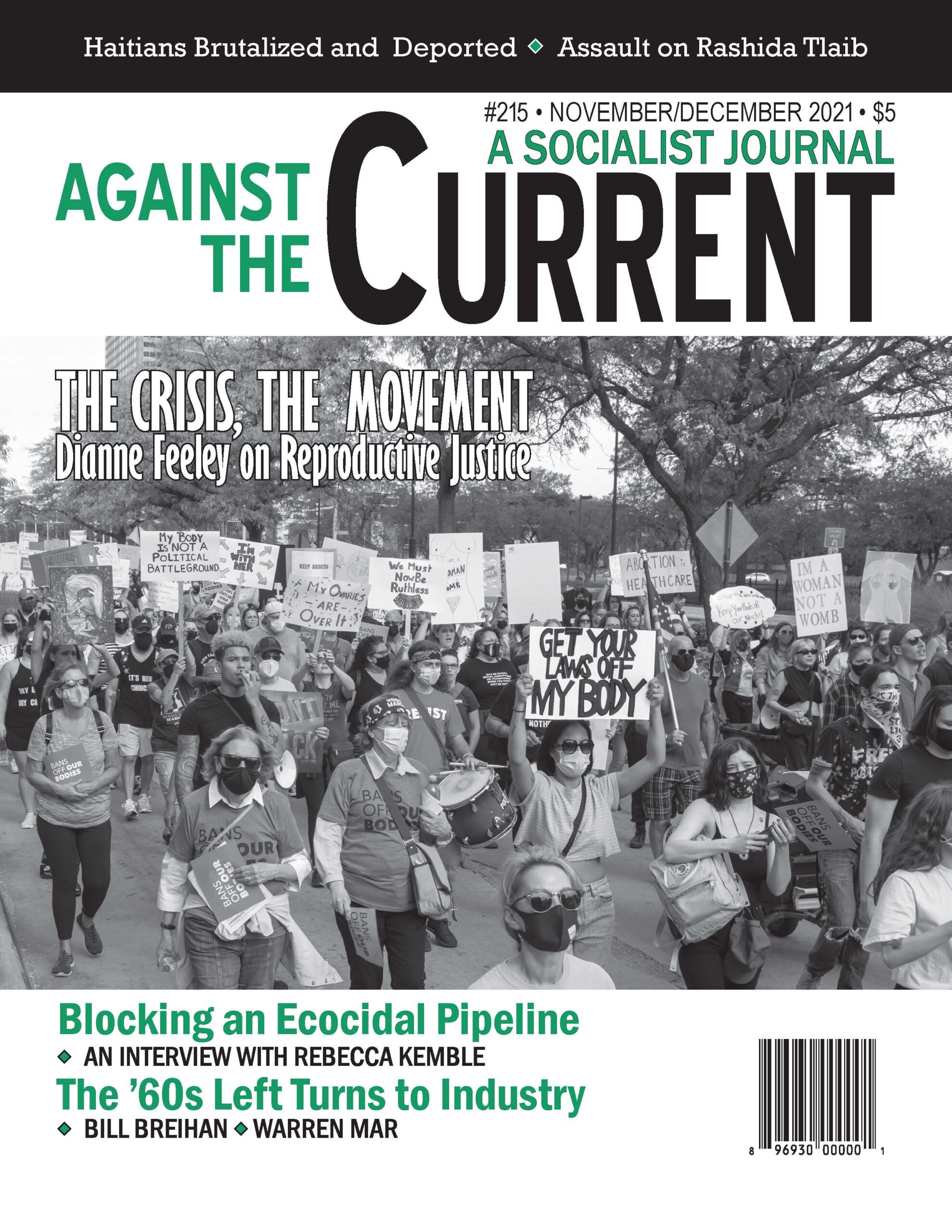

TENS OF THOUSANDS rallied, marched, and chanted for reproductive justice in 650 U.S. cities on October 2. Ranging in size from a hundred to 10,000-20,000, the actions came in response to the Texas anti-abortion law that went into effect September 1. The predominance of hand-made signs expressed defiance and determination: “My arm’s tired from holding this sign since the 60s”; “TEXAS: where a virus has reproductive rights and a woman doesn’t”; and “One day I just hope to have the same rights as a gun.” The overarching message was that we will not return to the era when abortion was illegal.

The Texas anti-abortion law bans abortions beyond the sixth week of pregnancy. Anyone aiding or abetting an abortion beyond that period could be sued: a doctor, a clerical worker at the clinic or a person who provided money, transportation or even childcare. Written to prevent legal challenge, it bypasses enforcement by the state and deputizes bounty hunters, rewarding them with $10,000 payoffs.

When the Texas clinics appealed to the U.S. District Court, the case was inexplicably postponed and sent to the U.S. Supreme Court. As the September date approached and the Court was still on summer recess, a truncated process resulted in a 5-4 ruling with the majority smugly justifying its position given the “complex and novel antecedent procedural questions.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor called the emergency ruling “stunning,” given that the law is so clearly unconstitutional.

Known as Texas Senate Bill 8 (SB8), the law was designed to shut down the state’s two dozen remaining clinics. An earlier Texas law, overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2016, required doctors who performed abortions to have admitting privileges at hospitals within a 30-mile radius and mandated that abortion facilities must meet costly and unnecessary specifications for their buildings.

The majority opinion in Whole Women’s Health vs. Hellerstedt struck down these requirements, noting that “Each [provision] places a substantial obstacle in the path of women seeking a previability abortion, each constitutes an undue burden on abortion access, and each violates the federal Constitution.”

The 2013 law was a test to see how many clinics would be forced to close through onerous regulations. Once closed, it’s difficult for clinics to find the resources and to reopen. Despite a favorable ruling, 40 clinics were whittled down to a mere two dozen. SB8 goes further by intimidating anyone willing to help end their pregnancy.

When SB8 went into effect last September, Texas clinics complied with the new law. Those beyond their six weeks were referred to out-of-state clinics.

Of course, that route involves more complex arrangements and higher costs for those already under the considerable stress of terminating a pregnancy. The appointments at the nearest clinic in Oklahoma skyrocketed, leading to additional wait times.

The Response

In response to SB8, a coalition of over 100 organizations under the banner of the Women’s March called a demonstration for reproductive justice on October 2 in Washington DC. Local initiatives, often organized by young women on social media, sprang up and linked to the Women’s March map. While the level of organization differed around the country, determination filled the air.

Five days after the successful actions, U.S. District Court Judge Robert Pitman issued an emergency injunction against SB8 at the request of the U.S. Department of Justice. In his 113-page ruling he stated, “From the moment S.B. 8 went into effect, women have been unlawfully prevented from exercising control over their lives in ways that are protected by the Constitution.”

The following day, six of the 24 clinics began to schedule patients although staff were frightened to resume services. They realize that if the law is ultimately upheld, SB8 allows bounty hunters to retroactively sue all who aided and abetted.

True to form, the Texas attorney general immediately appealed the case to the very conservative Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which quickly overturned Pitman’s injunction. Other state legislatures, most notably Florida, have threatened to pass their version of SB8 over the next few months. Since three of Trump’s appointees have been added to the U.S. Supreme Court, right-wing legislators have felt emboldened to move ahead and challenge Roe v. Wade on several fronts.

In 2018 Kentucky outlawed a surgical procedure used for second-trimester abortion. A federal court has ruled that law unconstitutional, issued a permanent injunction and denied an appeal.

The state’s secretary of health accepted the decision, yet the state’s attorney general demands to continue the litigation. The Court’s decision to hear oral arguments on what is a procedural motion indicates the majority’s interest in laws that outlaw abortion before there’s any possibility of viability outside the body of the pregnant person.

A Mississippi law that outlaws abortion at 15 weeks is on the Court’s docket. The hearing is scheduled for December 1 with a decision expected next spring.

Right-Wing Attacks

For 50 years the right wing has attempted to overturn the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision. They have won partial victories by passing a number of supposedly necessary requirements which result in infantilizing women.

Over the years anti-abortion fanatics have picketed and terrorized clinics, killed doctors who perform abortions, lied about the safety of abortion, and passed laws that set requirements unrelated to the safety of the pregnancy. These include parental consent for teenagers, requiring a waiting period between a first visit and the procedure, distributing unscientific “facts” to patients as well as mandating ultrasounds that are unnecessary early in a pregnancy. They also police sex education classes, and set up phony women’s health clinics to attract and then intimidate those seeking abortion.

The most important right-wing attack on abortion came in 1979 with the passage of the Hyde Amendment, which denies the poor Medicaid funding for most abortions. (During the seven years before the amendment was implemented, 300,000 were able to obtain abortion under Medicaid.) This is an amendment tied to the yearly budget and has been renewed by both Democrats and Republicans over the years.

Although President Biden eliminated the amendment with the $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill that would expand Medicaid, Senator Joseph Manchin (WV-D) announced at the end of September that he will not vote for that bill unless the Hyde Amendment is included. The attack on the poor, which disproportionally affects people of color, continues.

Despite the aggressiveness of the right-wing base in evangelical and Catholic churches, a nearly 60% majority public opinion opposes banning abortion. Yet the right wing wants to eliminate abortion and declare “fetal rights” beginning at the moment of conception. it has been successful in restricting abortion because we live in a society that judges women and poor people. For example, the right wing paints those who don’t have the resources to pay for the abortion procedure as sexually irresponsible. Those who seek abortion in the second or third trimester are particularly vilified.

Is our response strong enough?

The reality is that those wanting to end a pregnancy want to do so as quickly as they can. That’s why 89% of all abortions occur within the first twelve weeks. Yet this requires knowing where to access such services and having the money, time, and resources to get to a clinic. Those unable to do so were blocked by either a medical, financial or personal reason.

Reproductive procedures for women are judged differently than all other medical procedures. Why accept that the state should have a say about who will have, or when to have, or not to have, children?

Abortion (before “quickening”) and birth control were outlawed in the United States only in the 19th century and birth control became an issue with the rise of feminism in the early 20th century. But the challenge stalled out under the repression unleashed as the United States entered World War I. Without a feminist movement to shape it, birth control re-emerged in the 1930s. By the 1960s the right to abortion was key to the new movement. We initiated petitions and class-action lawsuits, testified at legislative hearings, and even picketed medical conventions, urging doctors and nurses to join us in demanding a repeal of these laws.

A Brief History of the Fight

By the 1960s it was estimated that at least a million U.S. women each year were undergoing illegal abortions, often under unsafe conditions. We organized speakouts where women testified about our experiences. In April 1971 the manifesto signed by 343 French actresses and cultural workers was published, declaring they had had abortions and demanding the law’s repeal. It shocked the world by revealing the reality for even many “successful” women.

This occurred within a burgeoning and international movement. Two years before, a group of undergraduates at McGill University in Montreal published the first edition of a scientifically informative Birth Control Handbook. It described and diagrammed women’s anatomy and the reproductive cycle.

The first edition of Our Bodies, Our Selves, published in 1971, raised a wide range of women’s health issues. While there had long been a phone number one could give to a friend “in trouble,” in Chicago the Jane Collective organized an underground clinic and carried out 11,000 safe and inexpensive abortions between 1969-73.

Feminist health centers flourished during this period, as women flocked to learn about our bodies. On the West Coast Carol Downer was arrested for teaching women to use yogurt to treat vaginal infections; the yogurt in the clinic’s refrigerator was confiscated as evidence.

After abortion became legal these clinics added abortion to their list of services. Since hospitals were never very interested in offering abortions, these feminist clinics, along with Planned Parenthood, became the infrastructure for abortion services.

By the end of the 1960s states such as Colorado and California had reformed their laws to allow for “therapeutic” abortions. Women who had “serious” health or mental health problems could obtain them when certified by a hospital committee. Mostly available to wealthier women, it was a humiliating process that was accessible to a relative few.

Also during this time, middle-class women who wanted to be sterilized had to jump through hoops in order to qualify while poor women, usually African Americans and Latinas —but also women considered mentally or physically deficient — were forcibly sterilized. Mexican American women, who had been sterilized without their knowledge during their delivery, learned of the procedure when they inquired about birth control. Nearly one-third of Puerto Rican women were sterilized.

The more radical element of the feminist movement saw how race and class were used to implement decisions about women’s bodies. We realized that the best way of advancing women’s rights was to defend the most vulnerable. We linked the demand to repeal abortion laws with one that exposed and opposed forced sterilization.

By the 1970s it was clear that the demand raised by the women’s movement was not to reform abortion laws, but to repeal them. Class-action suits were winding their way through several state courts.

Realizing that the New York state law was about to be struck down, the state legislators crafted an extremely progressive law: it had no residency requirement and allowed abortion through the 12th week of pregnancy. Legal abortion had become a reality! At the end of the first year, statistics revealed how safe abortions were. In essence, the New York law became the test case that would lead to the Roe v. Wade decision.

It’s true that Ruth Bader Ginsburg criticized the decision because it rests on the Supreme Court’s interpretation of privacy as a Constitutional right — a shaky edifice — rather than on the 14th Amendment’s due process and equal protection clauses.

Ginsburg also questioned the trimester framework established by the 1973 decision. By dividing a pregnancy into three stages, the ruling gave the state more say as the pregnancy progressed.

Before the fetus could survive outside the woman, that is, during the first two trimesters, legislation should concern only her health and safety. Only with fetal viability does the state have an interest. Yet late abortions are usually necessary when the woman’s life is in danger, or the fetus is malformed and unlikely to survive.

Nonetheless, we have a federal law against third trimester abortions. Here again the assumption is that politicians are better able to make an informed judgment than the pregnant individual. While defending the right to abortion outlined in Roe v. Wade, it’s now time to call for its extension.

Currently about 870,000 abortions are performed each year, with 30% carried out through a medical, not surgical, procedure (i.e. by pills — mifepristone and misoprostol). Given the growing percentage of medical abortion since the FDA approve these drugs in 2000, right-wing legislators have effectively prohibited telemedicine for abortion by mandating that the physician must be in the same room as the patient.

One in four women will have an abortion before the age of 45. That was the reality before abortion was legal, and while the number of abortions has decreased with greater access to birth control, it remains so.

Nearly half of those seeking abortion are poor (living below the federal poverty level) and another 26% low income. Almost 60% already have at least one child. People of color have approximately 60% of all the abortions while whites represent nearly 40%.

According to the Guttmacher Institute, by 2019 nearly 40 million women of reproductive age live in states considered hostile to abortion rights. The National Advocates for Pregnant Women note that in this hostile environment women are being increasingly arrested and sometimes convicted for miscarriages. They have been arrested for falling down stairs, drinking alcohol, giving birth at home, being in a “dangerous” location, having HIV, experiencing a drug dependency problem, or attempting suicide.

Beyond Texas

SB8 is an attempt to circumvent a derivative constitutional right through vigilante action that will render it meaningless. In essence, the Texas legislature is mirroring the approach of the former slaveholders after the Civil War.

Passage of the post-Civil War 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments abolished slavery as a legal institution and guaranteed the rights of citizenship to those who had been dehumanized. Yet within a dozen years a relentless counterattack resulted in “redeeming” the white elites, smashing what multi-racial democracy had been built and reducing the rights of former slaves through vigilante murder and intimidation.

With this tragedy in mind, we can look at social movements that have forced public officials to take positions they’d rather not. Today’s crisis opens up an opportunity to assert the right to a full program of reproductive justice. We should end the onerous restrictions on abortion, offer sex education based on science not superstition, provide universal and free contraception, along with an accessible public health system and creating a healthy environment in which to raise children.

And given the right-wing’s generalized attack, it seems obvious to ally with other social justice movements that face the same bullying enemies, from Black Lives Matter and Indigenous rights to environmental justice, rational gun control and voting rights.

November-December 2021, ATC 215