Against the Current No. 213, July/August 2021

-

Infrastructure: Who Needs It?

— The Editors -

Burma: The War vs. the People

— Suzi Weissman interviews Carlos Sardiña Galache -

Afghanistan's Tragedy

— Valentine M. Moghadam -

The Detroit Left & Social Unionism in the 1930s

— Steve Babson - On the Left and Labor’s Upsurge: A Few Readings from ATC

-

Detroit: Austerity and Politics, Part 2

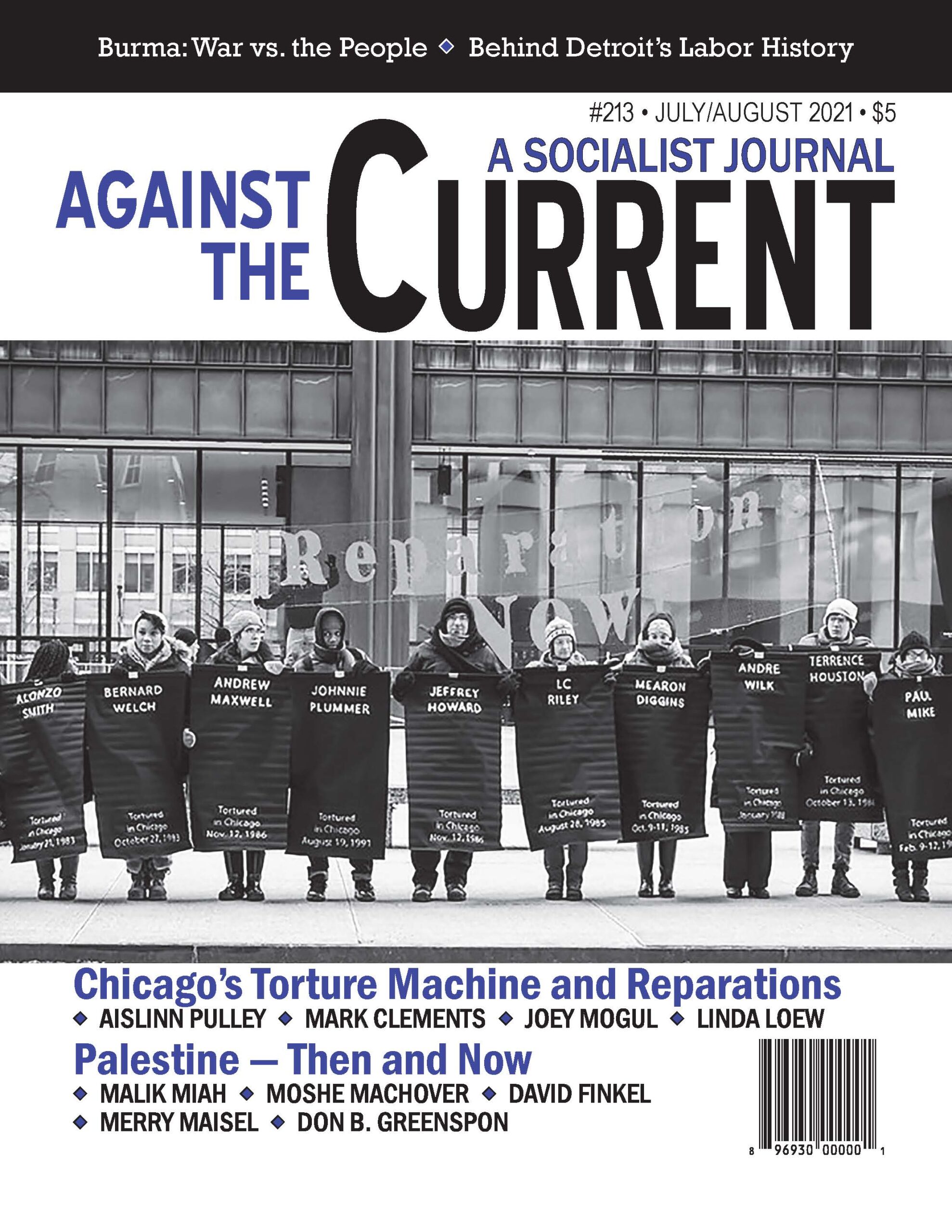

— Peter Blackmer - Chicago's Torture Machine

-

Reparations for Police Torture

— interview with Aislinn Pulley - Diana Ortiz ¡presente!

-

A Torture Survivor Speaks

— interview with Mark Clements -

Torture, Reparations & Healing

— interview with Joey Mogul -

The Windy City Torture Underground

— Linda Loew - Palestine -- Then and Now

-

Palestinian Americans Take the Lead

— Malik Miah -

Zionist Colonization and Its Victim

— Moshé Machover -

Conceiving Decolonization

— David Finkel -

Not a Cause for Palestinians Only

— Merry Maisel -

When Liberals Fail on Palestine

— Donald B. Greenspon - Reviews

-

Immigration: What's at Stake?

— Guy Miller -

Exploring PTSD Politics

— Norm Diamond -

A Life of Struggle: Grace Carlson

— Dianne Feeley -

Living in the Moment

— Martin Oppenheimer

Steve Babson

FOR LABOR ACTIVISTS pondering an uncertain future in the 2020s, there’s good reason to look back to the 1930s, a decade that began with the catastrophic collapse of organized labor and ended with the dramatic rise of a new movement. What can we learn from that stunning turnaround, heralded by the wave of sitdown strikes that swept across the nation in 1936-1937?

Nowhere was that social transformation more dramatic and far reaching than in Detroit, a city known in the 1920s as an exemplar of the anti-union, “Open-Shop” town.

That changed in a single sweep of militant action beginning in November, 1936 and lasting through the spring of the following year, a rolling general strike that made Detroit the nation’s leading union town. An estimated 100,000 workers walked off the job in those few months and 35,000 more barricaded themselves inside 130 workplaces, including auto factories, parts plants, department stores, restaurants, hotels, laundries, meatpacking plants, and cigar factories.

[For a brief list of readings on the left and labor upsurge, see next article. — ed.]

Three Myths

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it sometimes rhymes, as the saying goes. Any potential for a resurgence of workers’ power will certainly look different today, after decades of globalization, deindustrialization, and automation. But if there were underlying dynamics in the 1930s that rhyme with today, they are best understood if we first rule out the myths that often accompany a retelling of “labor’s giant step.”

The first myth is that widespread suffering during the Great Depression made the uprising of 1936-1937 inevitable, a view reinforced by the casual certainty of hindsight. In the first years of the depression decade, this was not how most people saw things.

Even for many pro-labor observers, the “inevitable” prospect was the continued disintegration of the American Federation of Labor. The AFL, hobbled by its near-exclusive focus on organizing skilled, native-born, white men, had no will or capacity for organizing mass-production industries where less-skilled workers predominated and where African Americans and women had become more numerous.

Material conditions and widespread suffering certainly defined the range of possible outcomes in the 1930s, but it was the human agency of leftwing activists that made some of these possibilities more likely than others.

Another myth focuses on the role of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his New Deal administration.

Conservatives and liberals alike point to FDR’s outsize role, the former to condemn him for meddling in matters best left to CEOs, the latter to celebrate him as a champion of the working class.

Both misrepresent the president’s actual role. He was, in fact, a reluctant meddler and an unreliable champion, favoring a toothless mediation of industrial disputes in 1934 and at first opposing passage of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) in 1935.

To his credit, he finally signed on to the NLRA’s partial protection of union organizing when it appeared to be the only alternative to the widening bloodshed of 1932-1935 — a time when employers refused to bargain and police and National Guardsmen gunned down striking workers.

Even after FDR signed the legislation, employers simply refused to obey the law and waited for the courts to overturn it.

Yet another myth is that workers spontaneously rose in opposition to these continued abuses, and did so “all in one mass,” as the United Auto Worker claimed in 1937. Popular histories abound with such imagery of unified and spontaneous militancy, much of it originating with participants and reported subsequently by journalists and some historians.

But that’s not how it happened with the rising of 1936, which began with a militant minority taking the first well-planned steps. With their success, an anxious and hesitant majority was then inspired to join the movement.

Two Questions

To plumb this history, we can begin with two questions. First, why were workers in so many different workplaces inspired to join the rolling general strike of 1936-1937, in contrast to the usual one-workplace-at-a-time organizing we commonly see today? Second, why did the sitdowns begin in the fall of 1936 and not, say, 1933 when conditions were actually worse?

To answer the why-all-at-once question, it’s important to remember that the economic and social crisis of the Great Depression was far more severe in Detroit than in most cities and towns. While the national unemployment rate peaked at an estimated 25% in 1932-1933, in Detroit the reserve army of the unemployed swelled to more than 50% of the working population.

The city was suffering the acute downside of its dependence on auto production: people in crisis save money for food and clothing, not a new car. As auto production plunged to just 25% of capacity, those lucky enough to find a job were taking pay cuts of up to 50%.

They also knew their days were numbered: auto work was still largely seasonal in these years, peaking in the spring and summer and tumbling dramatically in the fall and early winter, with no assurance you’d be called back to work unless you bribed the foreman.

The specter of joblessness was especially terrifying at a time when there was no social safety net. Unemployment benefits and Social Security weren’t established until 1935, and benefits were minimal even then.

On a daily basis, this industrial crisis was experienced primarily as a community crisis. Families struggling to survive on donated food baskets went hungry when charitable and mutual aid societies collapsed.

As thousands fell behind on rent and house payments, they faced eviction, homelessness and exposure. In the winter of 1932-1933, there was no disputing that some people in Detroit were dying of starvation and malnutrition. The only debate was how many.

In this industrial and community setting, it was members of leftwing parties who provided the only credible defense for working-class families. The AFL’s “business unionism” had focused primarily — and unsuccessfully — on delivering negotiated benefits to skilled workers. Progressives, in contrast, simultaneously took action in the workplace and the streets to define a class-based “social unionism” that mobilized workers both on and off the job.

On the job, it was the Auto Workers Union (AWU) that spearheaded this mobilization. A forerunner of the UAW, the AWU had been organizing since 1918 as an independent union led by socialists and communists. It now took the lead in 1933 when Hudson Motors, Murray Body, and Briggs Manufacturing slashed wages yet again, provoking a strike of 15,000 skilled and less-skilled workers.

As the police repeatedly attacked the picket lines at Briggs, the company managed to house hundreds of strikebreakers inside the plant and recommence production — a fact many activists later recalled when their chance came in 1936. The AWU failed to win bargaining rights, but this broad-based uprising did persuade the companies to rescind their recent wage cuts.

The Role of Activists

In the community, socialists led the resistance to eviction and hunger. Mayor Frank Murphy, a liberal supporter of FDR, did open several closed factories as shelters and food pantries for the unemployed, but these provided only limited relief for those in the immediate neighborhood.

For many Detroiters, the only reliable place to turn for support were the Unemployed Councils organized across the city by AWU activists and the Communist Party.

As the number of reported evictions peaked in Detroit at 150 a day in the summer of 1931, the Councils’ network of block captains and runners could often mobilize a crowd as soon as the sheriff entered the neighborhood.

Even when they could not stop the eviction, they would afterwards return the family and their furniture to the home. In many cases, they would reportedly bypass the disconnected gas and electric services.

Hungry families could also find free food at the soup kitchens and pantries organized by the 15 Unemployed Councils in the city, distributing food solicited from local merchants and farmers at Eastern Market.

The first public demands for unemployment insurance were raised by the Unemployed Councils in cities across the country, their rallies marked by signs highlighting the class disparities evident in the crisis: “Kill One, Go to Jail. Starve Thousands, Go to Florida,” as one Detroit sign read.

The Detroit-area Unemployed Councils also led the famous march on Henry Ford’s Rouge factory in 1932, after the Ford patriarch had disparaged thousands of laid off Ford workers as lazy no-accounts.

This “Hunger March” became an iconic moment in Detroit’s labor history when Ford guards and Dearborn police opened fire on the 4,000 unarmed marchers, killing five and wounding 50. Five days later, a funeral procession with upwards of 50,000 marchers paraded down Woodward Avenue.

Besides serving as a rallying point for Detroit’s hard-pressed workers, the Unemployed Councils were also incubating the broad-based union movement that would follow. Common to many biographies of future union activists in 1936-1937 was their baptism of fire in the Unemployed Councils, where they learned the basics of community mobilization and direct action.

When many of these activists found work in the reviving economy of 1934-1936, they also brought with them the experience of working in a multi-racial movement.

This alone would have been hard to imagine in the previous decade when the avowed candidate of the Ku Klux Klan, Charles Bowles, won majority support in the 1924 mayoral election — although denied office when thousands of his write-in votes were disallowed for misspellings.

At a time when most employers still refused to hire African Americans into anything but the worst jobs and when most AFL craft unions were whites-only, the Unemployed Councils represented something unprecedented. This was especially true on the city’s East Side, where Italian, Jewish and East European families still had Black neighbors.

African Americans became Council leaders in several cases, and one, Frank Sykes (a Communist Party member) became citywide Chairman.

The community-based mobilization of the early 1930s also brought women into a new prominence, their augmented role highlighted by the emergence of the Women’s Action Committee Against the High Cost of Living. Led by Mary Zuk, a former autoworker in Hamtramck, the Action Committee launched a boycott in 1935 to protest the rising cost of meat in an economy where wages had fallen so dramatically.

Marked by parades and mass picketing of markets, the boycott spread across metro Detroit and from there to Chicago and other midwestern cities. This was not a narrowly focused consumer movement: the Action Committee was initially headquartered at the International Workers Order, a left-wing mutual-aid society, and the demand for a 20% reduction in meat prices was supported by union

activists.

Phil Raymond, the AWU leader of the 1933 strikes, was a featured speaker at a rally of 5,000 boycotters in 1935. When the Action Committee sent a delegation to Washington, Irene Thomson, an African American, was among the five women who met with federal officials. Less than two years later, Zuk and other leaders of the Action Committee were key supporters of the sitdown strikes by 2,000 women cigar workers in Detroit’s major cigar plants.

In all these ways, the community mobilization of Detroit’s neighborhoods prefigured the emergence in 1935 of a broad-based and inclusive movement, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Having found common cause in the community, many workers were better equipped to find it in the workplace, despite the prevailing gender, racial and occupational divisions of labor.

“Solidarity” was not an abstraction for veterans of the Unemployed Councils and the meat boycott. For them it was a lived experience. When the UAW-CIO announced its presence in Detroit as a broad coalition of leftwing and centrist workers, it did so in the community as well with neighborhood clinics to screen for tuberculosis and a Renters and Consumers League to mobilize tenants and shoppers.

This community base was the link that tied together many otherwise separate workplaces and infused them with a common purpose based on social class.

UAW organizers would address the specific needs of their varied constituencies through the Polish Trade Union Committee, the Italian Organizing Committee, and the Negro Organizing Committee. But this diverse constituency was linked in the social unionism of the CIO, primed and ready for an unprecedented counterattack on Detroit’s Open-Shop employers.

Why 1936-1937?

The first Detroit sitdown occurred at Midland Steel, a supplier of auto frames for Chrysler and Ford. It’s no coincidence that this strike began in November of 1936, just weeks after Franklin Roosevelt had won reelection in an unprecedented landslide.

The election was, in effect, a referendum on the New Deal and the National Labor Relations Act, with FDR simultaneously declaring his support for union organization while also denouncing the men of wealth who opposed him. Frank Murphy, running for Governor, also aligned himself with labor, pledging he would never send the National Guard to break a strike.

Few on the left had any illusions that these promises could substitute for direct action. But they also recognized that something exceptional was happening: the leading candidates for office had not only pledged their support for a new movement of workers, but had promised they would not send troops to break their strikes. Both the Communist Party and the Socialist Party still ran their own candidates for high office in 1936, but neither party put any significant effort into these nominal campaigns.

The primary goal was to defeat the conservative opponents of the New Deal and validate the labor rights protected by the NLRA. At the same time, few on the left or in the CIO wanted to subordinate their campaign to the formal control of the Democratic Party. Labor and the left formed a Labor’s Non-Partisan League to conduct an independent campaign in support of FDR and Murphy.

The link that many labor activists saw between political action and direct action was made concrete within days of the election. “We defeated the bosses at the polls,” said one UAW flyer. “Now we can win our rights in the workplace.”

This time it would be the strikers who barricaded themselves inside the factories, unlike 1933, when strikebreakers had occupied the safer ground inside the plants.

The first sitdown at Midland Steel was led by Wyndham Mortimer and “Big John” Anderson, both aligned with the Communist Party. They saw this carefully planned seizure of the factory as part of a deliberate effort to escalate the struggle for labor rights and win recognition for the UAW.

Among those elected to the strike committee was Oscar Oden, a Black production worker. The nearby Slovak Hall meanwhile served as a strike kitchen. Weeks later a second Detroit sitdown began at Kelsey Hayes Wheel, led by Walter and Victor Reuther, both aligned with the Socialist Party.

Here, the sitdown included women production workers as well as men, with the nearby Polish Falcons hall serving as headquarters and strike kitchen. Both sitdowns relied on this community base and both won union recognition for the UAW.

UAW organizers in Michigan waited until December 30, two days before Governor Murphy’s inauguration, to launch their sitdowns at the Fisher Body plants in Flint and the Cadillac plant in Detroit. Here again, most of the organizers and lead activists were socialists and communists. Governor Murphy, honoring his pledge, only sent the National Guard to Flint after city police had attacked the sitdowners.

In Flint, as in the preceding sitdowns in Detroit, the occupiers were acting on behalf of a clear majority who favored unionization, but the number of actual sitdowners was a small fraction of the workforce. This was the militant minority, prepared to risk their jobs and their lives to win union recognition.

When GM finally agreed to recognize the UAW on February 11, 1937, the floodgates opened in Detroit and elsewhere as thousands more saw the power of the movement’s new tactics and the dramatic change in the government’s response.

That change was manifested not only at the state and federal level, but also at the local level, especially in the city of Hamtramck, home to the giant Dodge Main plant. Here, independent action by labor and the left took the form of the People’s League, led by Mary Zuk, the veteran organizer of the meat boycott.

Zuk won election in 1936 to the Hamtramck city council, where she championed ordinances to support union organizing and prohibit racial discrimination in the distribution of welfare benefits. When 6,000 workers launched a well-planned occupation of Dodge Main in March of 1937, Hamtramck’s police were on call to help UAW organizers patrol the surrounding streets.

For conservatives, this all had the appearance of social revolution, particularly given the prominent leadership role of communists and socialists. The sitdowns did mark a watershed in popular thinking about labor rights and mass mobilization, but the leftwing leaders of this movement tailored their demands to the progressive, but less radical, aspirations of the movement’s base.

The seizure of factories, hotels and department stores was more akin to a citizens’ arrest than a revolutionary challenge to private property. The companies had refused to abide by the NLRA, had continued to promote company unions, and had illegally fired union supporters. In response, the sitdowners sent a simple message: obey the law and recognize our union, then you’ll get your property back.

This hardly ended the struggle. Internal union battles, Red scares, racial conflict, and tectonic shifts in government policy would slow and finally compromise the consolidation of a militant and inclusive movement.

But the social unionism that had broadened the base of Detroit’s labor movement in the 1930s continued to sustain that link between the workplace and the community into the next decade.

By allying with progressive Black ministers like Reverend Charles Hill, the UAW was able to defeat Chrysler’s attempt to recruit Black strikebreakers in 1939. In the war years that followed, the UAW, in turn, supported the desegregation of production jobs and fought the “hate strikes” of white workers who opposed this breach of the color line.

Thereafter, the struggle for Black civil rights was germinating inside Detroit’s factories, led by the integrated union committees that occupied segregated restaurants around the plants, forcing them to serve Blacks and whites alike.

Social unionism in these years also took the form of prolonged campaigns for universal healthcare and affordable housing. It even took the form of a demand during the 1945 GM strike that wage increases be paid for out of profits rather than price increases forced upon the public.

Today, union organizing faces many new challenges in an economy driven by subcontracting, service jobs, and gig work. Yet many of the same social issues are still with us — the struggle for human rights, universal healthcare, affordable housing, and an end to profiteering.

All these issues still rhyme.

July-August 2021, ATC 213