Against the Current No. 213, July/August 2021

-

Infrastructure: Who Needs It?

— The Editors -

Burma: The War vs. the People

— Suzi Weissman interviews Carlos Sardiña Galache -

Afghanistan's Tragedy

— Valentine M. Moghadam -

The Detroit Left & Social Unionism in the 1930s

— Steve Babson - On the Left and Labor’s Upsurge: A Few Readings from ATC

-

Detroit: Austerity and Politics, Part 2

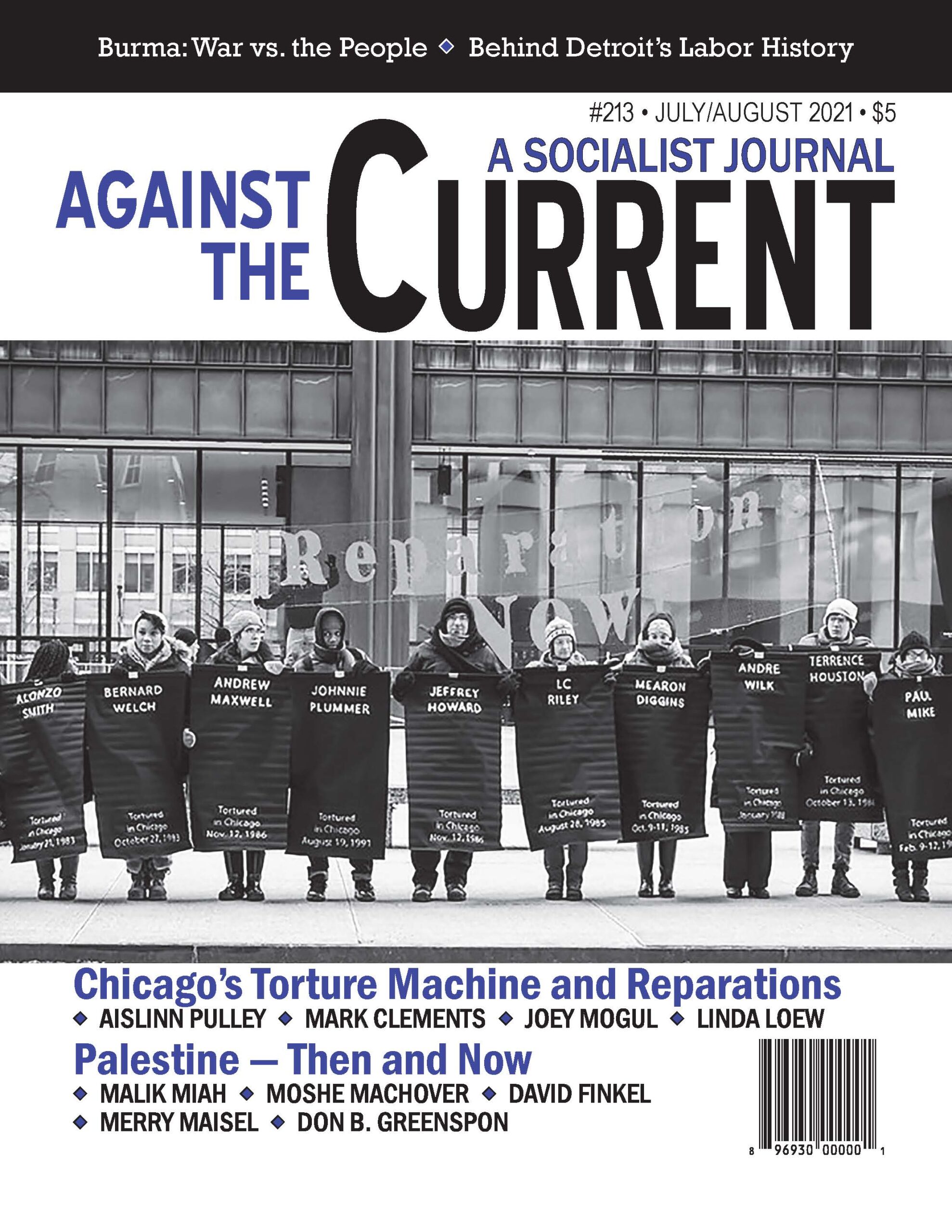

— Peter Blackmer - Chicago's Torture Machine

-

Reparations for Police Torture

— interview with Aislinn Pulley - Diana Ortiz ¡presente!

-

A Torture Survivor Speaks

— interview with Mark Clements -

Torture, Reparations & Healing

— interview with Joey Mogul -

The Windy City Torture Underground

— Linda Loew - Palestine -- Then and Now

-

Palestinian Americans Take the Lead

— Malik Miah -

Zionist Colonization and Its Victim

— Moshé Machover -

Conceiving Decolonization

— David Finkel -

Not a Cause for Palestinians Only

— Merry Maisel -

When Liberals Fail on Palestine

— Donald B. Greenspon - Reviews

-

Immigration: What's at Stake?

— Guy Miller -

Exploring PTSD Politics

— Norm Diamond -

A Life of Struggle: Grace Carlson

— Dianne Feeley -

Living in the Moment

— Martin Oppenheimer

Norm Diamond

Psychiatry, Politics and PTSD:

Breaking Down

By Janice Haaken

Routledge Press, 2021, 196 pages, $49 hardcover.

“Try as you might, want it ever so much, things are out of your control, even when they are in your mind, or especially because they are in your mind. The mind is a funny animal. If it were just conscious thought; or if conscious thought was something we could control; or if unconscious thoughts were conscious; or if moods were amenable to our desires…then maybe things could work. Things like … the project of sanity itself. Just make it happen!”

“But no. You’re swimming in a river. You can get carried out to sea on riptides not of your making, or at least not under your control. You can find yourself swimming against a current much stronger than you. You can drown.” —Kim Stanley Robinson(1)

THREE DAYS AFTER the recent presidential election, a friend who had spent hours each day for months calling potential voters, wrote me that she was suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

She was referring not only to the energy she had expended but to the disappointing results (in North Carolina), to the poor information she’d been furnished about the people she’d be phoning, and to the general incompetency of the organization that sponsored her calling.

But was this really PTSD? In the relatively short history of the concept, its meaning has morphed and gone in two different directions: a narrowing technical diagnosis and an ever-broadening use in common parlance.

Janice Haaken is a clinical psychologist, filmmaker, and author of two prior iconoclastic books in the realm of psychoanalytically-influenced feminist theory.(2) Her new book explores the introduction of PTSD the concept, the political movement that gave rise to it, its potential as political critique and its subsequent taming.

As between the two kinds of usage, popular and more technical, Haaken’s focus is more on the professional. In both its recondite language and its orientation, this is a book for and primarily about psychiatric practitioners. It examines economic and cultural shifts within the profession, the tensions in relation to patients when psychiatrists are called on to make judgments about who is deserving of care and recompense, and the specific diagnosis of PTSD as a way of managing constraints on therapists’ powers and choices.

That orientation aside, the book’s implications for political activism are great. It is also, in the brilliant words of Haaken’s radio interlocutor, “an insightful meditation on how we understand and deal with human suffering in the context of late stage capitalism.”(3) (Full disclosure: the interviewer was my wife.) Further, as nearly all of Haaken’s writing, it is a book about storytelling.

The Triggering “Event”

“PTSD, the great affect of our time.” —Kim Stanley Robinson

Something happens. Let’s call that an “event,” and grant for the moment that it might be stressful. An individual or individuals undergo that event, their experience influenced by what they bring to the event from their past. Depending on their response and their access to resources, a clinician may come to be involved.

Historical and cultural factors shape how both the individuals and clinician perceive and mentally process the event. Social forces shape the diagnostic categories available and constrain their application. Political influences may enter.

Underlying the event’s interpretation and the clinical response are particular conceptualizations of normality and of the mind, conceptualizations that themselves vary from time to time, culture to culture.

The archetype “events” on which Haaken focuses are traumas of military action and sexual assault, singular events resulting in individualized suffering. But what of the trauma of a life lived in poverty, of exposure to police repression and brutality, of spousal abuse, of the many and pervasive forms of racism?

The initial impulse behind the PTSD diagnosis also recognized sustained and/or collective suffering. Haaken’s starting point is the contrast between that expansive understanding of trauma and the narrower range of what the diagnosis has become.

PTSD as a mental health diagnosis was a product of the radical politics we associate with the 1960s. That broader movement, with its antiwar, civil rights and feminist strands, also had an anti-psychiatry component.

Working within as well as outside the profession, this part of the movement indicted existing psychiatric practice for not recognizing the societal factors behind people’s suffering. It rejected the prevailing diagnostic premises that only people who were already damaged would be susceptible to persisting traumatic response.

This critique valued the “madness” of the marginalized as offering insights into the nature of the larger society, and condemned the profession for over-pathologizing divergent mental states and over-medicating.

The PTSD diagnosis was, in short, progressive, yet also built on a contradiction: a revolt against psychiatric hegemony that simultaneously looked to the profession for legitimacy.

When PTSD was eventually adopted into the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), the bible of the psychiatric profession, it was the first recognized diagnosis to acknowledge a cause of mental suffering for which the broader society carried responsibility.

One factor in its official adoption was the crisis in the profession resulting from neoliberal capitalist cutbacks and the undermining of earlier mental health programs. But official acceptance brought constraints.

This is where Haaken’s account offers broader lessons on the cooptability of reforms, and is poignant in its recognition of what might have been. Now part of the medical establishment’s apparatus, the focus has shifted from collective suffering to managing individual symptoms. Social problems have again been narrowed to clinical issues.

Whereas PTSD advocacy still enables raising a limited set of grievances, primarily military and sexual, they are channeled into singular events, one-time traumas, with a premium on dramatic telling to earn access to resources. The U.S. military now simply incorporates treatment for PTSD into its budget as an expected and calculable cost.

The Problem of Context

“Everyone alive knew that not enough was being done, and everyone kept doing too little. Repression of course followed, it was all too Freudian, but Freud’s model for the mind was the steam engine, meaning containment, pressure, and release. Repression thus built up internal pressure, then the return of the repressed was a release of that pressure. It could be vented or it could simply blow up the engine.

“A hiss or a bang? The whistle of vented pressure doing useful work, as in some functioning engine? Or boom? No one could say, and so they staggered on day to day, and the pressure kept building.” —Kim Stanley Robinson

Psychiatry, Politics and PTSD is richer than I can indicate in a short review, offering insights into the nature of memory, among other PTSD-related topics. The book also has thoughtful cautions relating to political practice, for instance to human rights campaigns that base their practice on dramatic stories of victimization.

But I do want to express some reservations, both about what the author says and what she assumes and omits.

Haaken claims to have set the origin of the diagnosis and the struggle over its legitimacy in its social context. This is a large claim that comes with high expectations.

Social context, people’s experience of their surroundings and interactions is indeed crucial in understanding when concepts appear and especially when they gain acceptance. As part of an explanation it operates at many levels, most importantly on the premises that underpin concepts, on the models available for formulating our specific thoughts.(4)

Understanding any and everything in its social context is important politically. Done well, it suggests that whatever is being explained could have been different had the society out of which it came been organized differently. It is, inherently if implicitly, a challenge to the status quo.

To offer an explanation at that level, Haaken would have had to show how people’s social experience changed in the era she writes about and how those changes drove a search for new ways of making sense of the world, new premises that resulted in a changed understanding of the mind.

An analysis at this level would have gone a long way toward an explanation rather than what the book offers, primarily a retelling of what happened. Instead, what she emphasizes is the fact of a political movement, surely a contributing factor but far from sufficient as an explanation.

Was there a reconceptualization of “mind” coming out of the 1960s, and did this shape the formulation and acceptance of PTSD as a diagnosis? Haaken begins to address this, mentioning historically changed conceptions of psychic normality, but stops short.

The book also contains a number of mistakes and surprising omissions, some of them significant. Freud did not study with Charcot in the 1870s (94) but rather a decade later. Had he been at the Salpêtrière at the time Haaken puts him, he would have encountered a very different class of patients than he in fact did, with potentially different implications for his later theorizing. Salpêtrière patients in the 1870s were those suffering from the after effects of the 1871 massacre of the Communards.

And the U.S. economic crisis during which World War I veterans marched on Washington demanding promised benefits was in the 1930s, 1932 for the march, not a decade earlier. (119) Troubling in this day and age, Haaken refers multiple times to veterans’ benefits, now and in the past, without acknowledging the racial disparity in accessing those benefits.

There is a further omission that I find puzzling because it is so obvious: the clinically acknowledged PTSD resulting from torture.(5)

Wars and Trauma

“Post-traumatic stress disorder, yes, but this phrase always hid more than it revealed.” —Kim Stanley Robinson

Some of the book’s limits may stem from a seeming advantage: the unique access the author obtained to the U.S. military. In making her movie Mind Zone: Therapists Behind the Front Lines, Haaken and her crew were permitted to film on military bases in the United States and even in Afghanistan.

Embedded, she must have struggled to maintain critical distance from the perspective of her hosts. The book was an opportunity to transcend her “fly on the wall” approach to filmmaking, but is not always successful in that regard.

A prime example is in her treatment of war. She is insightful in the ways that wars have been laboratories for Western psychology, and subtle in her appreciation of the tensions for military psychiatrists between the priorities of treating soldiers’ suffering and restoring them to action.

But other than one brief mention specific to how U.S. military engagements have changed since Vietnam (61) she tends to treat “war” as if it were the same now in all contexts, bringing the same meaning and mental health consequences.

I would suggest, to the contrary, that military action fought in defense of one’s country, village or family does not have the same mental health consequences as imperial invasion. Nor does war waged as part of a revolutionary uprising.

The Mayan guerrillas I knew well in Guatemala did not and have not seemed to suffer from PTSD. They too were wounded, startled by surprise attacks, saw comrades and relatives killed in firefights. I would not romanticize their response. But they were part of a cause and a community and a culture that both prepared and supported them in ways that U.S. soldiers do not have.

Haaken knows that Western diagnoses don’t necessarily travel well. (144) And she knows that different cultures deal differently with human suffering. Indeed a large component of every culture is an explanation and response to suffering’s inevitability. But, as is the case with “war,” she tends to write as if her subject and conclusions had universal scope.

In that respect, the reach of Psychiatry, Politics and PTSD is beyond its grasp. In the large area of what it does grasp, however, the book is thought-provoking, an insightful meditation indeed.

Notes

- All the epigraphs are from Kim Stanley Robinson’s important new novel, The Ministry for the Future, in which PTSD is a motif, as is going against the current.

back to text - Pillar of Salt: Gender, Memory, and the Perils of Looking Back, Rutgers University Press, 1998; Hard Knocks: Domestic Violence and the Psychology of Storytelling, Routledge, 2010.

back to text - The interview may be heard at https://kboo.fm/media/83380-breaking-down

back to text - I’ve written extensively elsewhere about the social roots of conceptualization in science. See, for instance, Norm Diamond, “The Politics of Scientific Conceptualization,” in Levidow and Young, Science, Technology and the Labour Process, CSE Books, England, 1981. Also Norm Diamond, “Generating Rebellions in Science,” Theory and Society, Amsterdam, winter, 1976.

back to text - For an excellent treatment, politically astute, cf Nancy Caro Hollander, Uprooted Minds: Surviving the Politics of Terror in the Americas, Routledge, 2010.

back to text

July-August 2021, ATC 213