Against the Current No. 208, September/October 2020

-

The Pandemic and the Vote

— The Editors -

"Good Trouble, Necessary Trouble"

— Malik Miah -

Black Lives Matter & the Now Moment

— Anthony Bogues -

Why Send Troops to Portland?

— Scott McLemee -

A Victory, an Unfinished Agenda

— Donna Cartwright -

Your Postal Service in Crisis -- Why?

— David Yao -

Solidarity's Election Poll

— David Finkel for the Solidarity National Committee -

Why Green? Why Now?

— Angela Walker -

Opening Up the Schools?

— Robert Bartlett -

Toward a Real Culture of Care

— Kathleen Brown -

Toward Class Struggle Electoral Politics

— Barry Eidlin interviews Micah Uetricht & Meagan Day -

C.T. Vivian, Organizer and Teacher

— Malik Miah -

Behind Lebanon's Catastrophe

— Suzi Weissman interviews Gilbert Achcar - Support for Mahmoud Nawajaa

-

Dead Trotskyists Society: Provocative Presence of a Difficult Past

— Alan Wald -

Nonviolence and Black Self-Defense

— Dick J. Reavis - Reviews

-

Experiments in Free Transit

— Joshua DeVries -

Studying for a New World

— Joe Stapleton -

The Fight for Indigenous Liberation

— Brian Ward -

At Home in the World

— Dan Georgakas -

The Larry Kramer Paradox

— Peter Drucker - Larry Kramer, a Brief Biography

Anthony Bogues

WE LIVE IN an extraordinary moment. One in which many cross currents tussle for sustained dominance. A moment when armed white supremacy groups attempt break-ins to legislative offices in states like Michigan. One in which the science of contagion is in battle with a myopic individualism, wherein the wearing of a mask for medical protection becomes a signifier for a political symbolic battle around hegemony.

All this occurs in a moment when there is a historic pandemic, which should make us as a human species reflect on our contemporary ways of life. A pandemic that exposes the structures of the American health system, where race and class determines those who will survive and live and those who disproportionately die.

In the midst of this crisis in which lockdowns and shelter-in-place are everyday practices, we witnessed one of the most significant global protests that the world has seen for some time. The protests upended many commentators, shattered many conventional wisdoms about politics, and at least for a time punctured the everyday normal to which many of us had become accustomed.

So what was at the root of this upsurge? What are its significances? And, therefore, how might we understand it?

In the epigraph to the first chapter of Black Reconstruction (1935), W.E.B. Du Bois writes about “How black men, coming to America … became a central thread to the history of the United States, at once a challenge to its democracy and always an important part of its economic history and social development.” That challenge has historically been the touchstone for both American democracy and its civilization.

Racial slavery was a cornerstone of capitalism. It is not that racial slavery laid the foundation for capitalism; rather racial slavery, the plantation slave economy, the African slave trade were themselves practices of capitalism. At the core of the inauguration of capitalism was not the factory system with its wage labor but the slave plantation, unfree labor and a network of credit and debt arrangements.

In Debt: The First 5000 years (2011), David Graeber points out how the Atlantic slave trade depended upon a system of debts and credits. Within this system emerged various institutions we now associate with capitalism from bond markets to brokerage houses.

There was also the emergence of major companies whose chief functions were linked to slave trade, financing plantations and other aspects of the European colonial project. Here one can refer amongst others to the Dutch West India Company, the French Société de Guinée, and of course, the Royal African Company of England.

At the core of what historian Catherine Hall calls this “slavery business” was the African captive who became an enslaved person. The late African American theorist Cedric Robinson called this historical process “racial capitalism.”

The Enslaved Black Body

The enslaved body as the Caribbean historian Elsa Goveia said was “property in person.” It was a body that produced commodities, while itself commodified. The black female enslaved body reproduced this process three times over: as a body-producing commodity, while itself a commodity, and then through sexual violence being a reproductive body of enslaved labor.

The plantation was a site of generative violence of commodification. Capitalism was inaugurated through the various violences enacted upon the enslaved black body.

Exploitation was established upon the foundation of unfree labor. That is the history of capitalism: not a stages theory of transition of societies from one mode of production to another, but rather a historical process of generative violence upon the bodies of the African enslaved.

In such a history the body is not secondary, it is the source of the methods, the several ways, of practices which turn the human into an enslaved dehumanized thing. For creating such a historical process colonial and planter power needed to construct forms of life, ways of thinking, construct modes of being human that would at least for a time guarantee the full reproduction of a society.

To put this another way: exploitation requires forms of domination, and the latter requires ideas and practices which the dominant elite and others accept. This is about the manufacturing of what Gramsci calls “commonsense,” a kind of naturalized underpinning of a society, an ideational glue which holds society together.

In slave and colonial societies violence was regularized as a technique of rule because in such societies might was right. And while this was so these orders also ruled by means of a set of ideas and practices about who was human and who was not.

Racialized “Common Sense”

All nations as we know are an “imagined community” and as such we search for what glue bind the nation together. In America, the glue that has bounded the society together is not the fiction of America as an idea, the exception of the “City on the Hill,” rather it has been anti-black racism.

What Du Bois calls the “wages of whiteness” became the naturalized common sense which structured the everyday practices of living. Anti-black racism has a long history, founded within the matrices of the generative violence of the African slave trade and elaborated in plantation slavery through a complex system of customs and legal codes.

It was codified in human systems of classification promulgated by European natural historians in the 17th century, mapped by Christian doctrine, whereby some human beings had souls and some not; and then, in the 19th century, became re-codified through the so-called scientific studies of skulls.

Phrenology was a pseudo-science of the study of the mind, in which it was said that Africans were inferior because of the size of their skulls: since the brain was then thought to be located in the skull. Ultimately, when science made it clear that there was no scientific basis for anti-Black racism, then culture became a terrain to explain the supposed inferiority of blackness.

So blackness as visual marker produces within the dominant common sense the death of the Black person. Black life becomes disposable, is a lack, has no interiority, is locked upon itself. As a visual marker, the black body has no escape. Its public presence is an affront, it must be tamed, put back in its place. It must be not allowed to breathe, because breath is life and for the black body to breathe means it has life.

This is not primarily an American phenomenon. The history of racial slavery in America, the inauguration of Jim Crow and formal segregation, given the imperial power of America on the world stage created the illusion that there was a special American race problem.

All societies of course have their own historical specificities, but anti-Black racism was not an American feature alone. What Du Bois called the “color line” was embedded in the world because racial slavery and colonialism were parts of a global system ruling much of the world from the 15th century Columbian voyages onwards.

The anti-Black racism of European colonial powers drew from racial theories created in America, the Caribbean, the historical encounters between Europe and Africa. South African apartheid drew some of its resources from the structures and practices of American Jim Crow.

In all this the black body was the disposable surplus; not the other but the irremediable non-other, that which could not be fully included into the body politic of the given nation. Such an irremediable body, always on the outside, challenges the very meaning of democracy itself. It is why struggles around anti-Black racism shake the society, indeed call Western civilization into question.

Challenging the Foundations

If we agree historically that the foundation of the capitalist West was racial slavery and colonialism and the accompanying genocide and attempted genocide of the Indigenous populations, then what we are witnessing today are the challenges to this foundation.

Capitalism is not just an abstract economic system as Marx made clear long ago when he noted that economic relationships are always between people. To rule, to be able to reproduce itself, any social system creates ways of living, modes of being human as it is then understood. Historically and in the present, anti-Black racism and the creation of whiteness and of white supremacy was both a way of life and a signifier of being human.

It is not just an ideological belief but rather a naturalized common sense that in many ways functions like a fantasy, one which has material life and consequences. Common sense as well in part is constructed by the historical understandings of a society about itself.

We are, as humans, historical beings that make sense of ourselves through memories of the past. We take from that past to make the self. In societies where the past has been a historical catastrophe, where regularized violence operated as “power in the flesh” making the “human superfluous,” that past becomes a critical way to establish the grounds for inhumane ways of life.

America’s unwillingness to confront the fact that it was a slave society since its founding as a British colony; that practices of settler colonialism wreaked havoc on the indigenous population, along with Europe’s unwillingness to confront its own history as multiple colonial powers; these now provide a dominant common sense which structures the present.

Yet as the poet and thinker Aime Cesaire noted in 1955: “Between the colonizer and the colonized there is room only for forced labor, intimidation, pressure, the police, taxation, theft, rape, compulsory crops … no human contact, but relations of domination and submission.”

This history is elided by European countries. It is a history made visible through the various pacification campaigns, the genocide of the Herero people in Namibia, and under Belgian King Leopold the regular cutting off of the hands of the Congolese people.

It is a history codified through forms of rule which created the African subject into a “native” and turned various African social and political formations into tribes. History, however, lives in the present and becomes memorialized into the public landscapes of monuments, an encoded system of public signs which enact meanings in the public domain.

So when the Black Lives Matter Movement and those activated by it demand the removal of monuments, they are engaged in a move of symbolic insurgency to get rid of the public landscapes of the everyday violent historical monumentalization in the present. This happens in America, in South Africa, the UK. And continental Europe cannot escape the fire this time.

After the Murder of George Floyd

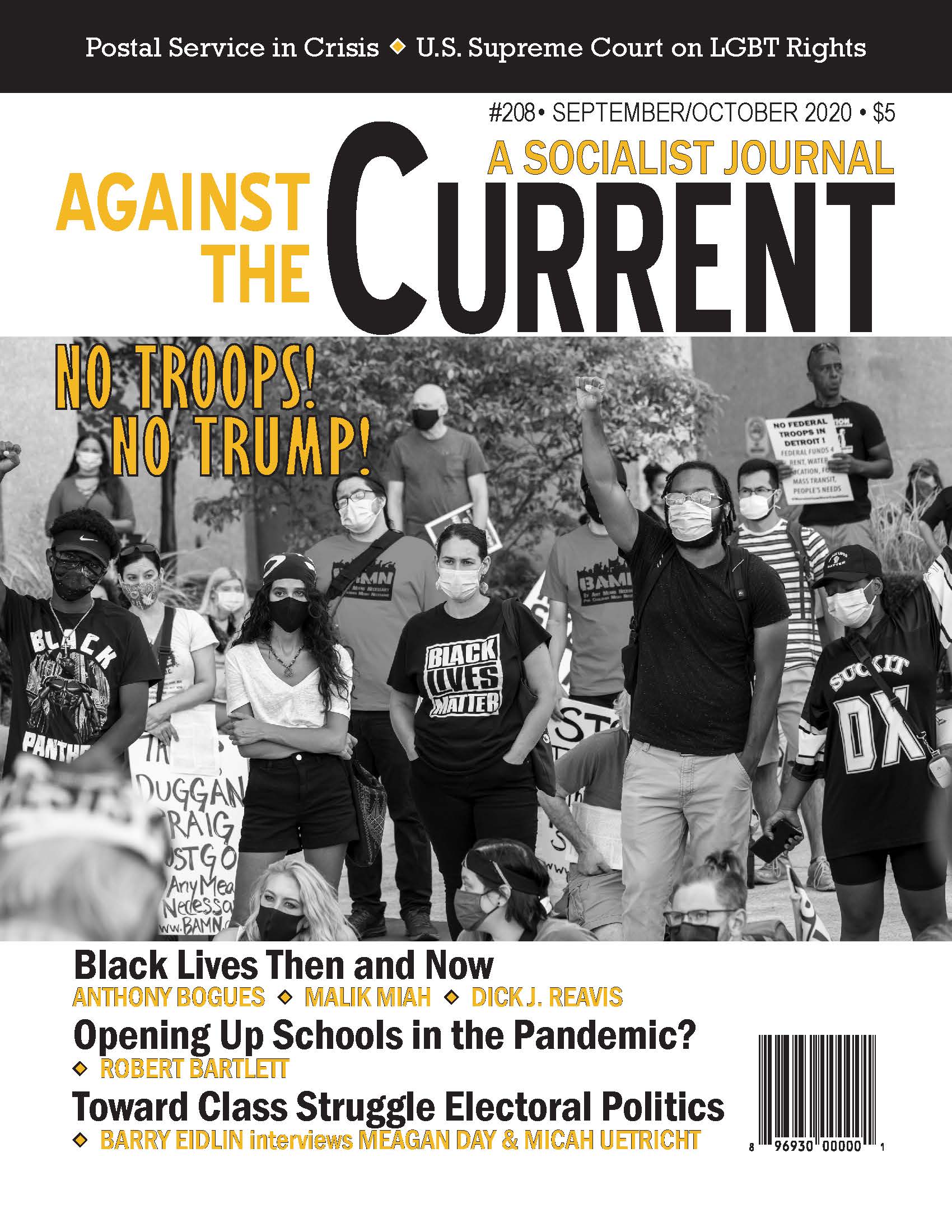

So here we are. For over a month there have been in America the single largest protests in America’s history, ignited by the public lynching of George Floyd who cried out “I can’t breathe” before being murdered, and then died with the words “Mama” on his lips. In that modern lynching scene, for nearly nine minutes we witnessed the meaning of anti-black racism.

Yes, it was the policeman who kneeled down on his back and neck. Yes, the American police force were operating like modern day slave catchers. But there was something else, and that something else was the casual nonchalance, the non-recognition that Floyd was human. It was the nonchalance that Floyd was just another disposable black body.

The daily confrontation between Black men and increasingly Black women with the police is the nodal point where anti-black racism is most visible. In this nodal point there is no pretense. State authority expresses itself that might makes right, that Black life does not matter. This is so in Brazil, in parts of Europe, the Caribbean, the United States of America or indeed in parts of Africa. Here ordinary Black life does not matter.

After the death of Trayvon Martin in 2013 a group of Black feminists, Patrisse Khan-Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi, formed the organization which became known as “Black Lives Matter.” Today the name of the organization has become a political banner igniting the political imagination of both Black and white around the world.

There is a rich historical current in which Black revolts/uprisings have catalyzed various struggles around the world. In the 19th century the dual Haitian revolution inspired Greek anti-colonial figures fighting against the Ottoman Empire when some of them wrote to the Haitian government requesting arms and political support.

We recall how what was then called “Negro Revolt,” the Black uprisings in the 1960s, influenced feminist and antiwar movements around the world. In all this the African American spiritual “We Shall Overcome” became a clarion political message of many movements. So why, might we ask, does Black Lives Matter at this moment become transformed into a catalytic political banner, one which has engaged the political imagination of thousands?

I return to Du Bois: Racial slavery was the foundation of America and, I would argue, of the making of the modern world. As a form of domination its very core was the double and triple commodification process I addressed earlier. It was about making non-human another human being.

As a generative historical process, it lasted for centuries. That is a special form of domination which not only required violence but creating another kind of human being, one who would be surplus and disposable. It also created the conditions for Black struggle to be catalytic, a point the Caribbean historian and radical thinker C.L.R. James made in 1948. When living underground in the USA he noted in a seminal essay, “The Revolutionary Answer to the Negro Problem in the United States” that “this independent Negro Movement is able to intervene with terrific force upon the general social and political life of the nation.”

Black Lives Matter became a political banner because it challenges continued racial domination, its deep rooted legacies and consequences . It says we are human. As such it demands that the society should be transformed to create new ways of living. It not only therefore exposes police brutality but calls to order the entire historical foundation on which Western civilization rests, which is why getting rid of the historical monuments which venerate the West has become so crucial.

Why a New Historical Moment

While part of a historic Black Liberation tradition, BLM political organizational methods have also developed critiques about Black masculinity. Given all this, Black Lives Matter as a political banner is world-historic. And here the reader might pause and wonder why?

Let us return to the making of the modern world; to the ways in which anti-Black racism continues in the after-lives of racial slavery to dominate black life as it has done so for centuries. So when there are sustained protests against the institutional and everyday forms of anti-Black racism and this happens on the global stage, is this not world-historic?

The current global protests are world- historic because they confront the entire panoply and edifice that built the modern world. They are also world-historic because they posit different methods of political organizing which breaks from previous forms of radical Black movements.

When the movement demands that monuments, which invoke the past and undergird the present, must fall, it draws from the earlier struggles of South African students and the Rhodes Must Fall Movement (bringing down statues of Cecil Rhodes, a colonial founder of white supremacy in southern Africa — ed.).

It demands abolition, making that word capacious, creating a new political language not just about abolishing prisons but demanding the opening of a new space, invoking the radical imagination to think of new ways of life. If many social and political radical movements have paid attention only to the state and the economy as structures of the present, Black Lives Matter is attentive to the history of the structures and their underlying assumptions and common sense.

We are indeed in a new moment. Some say this moment feels different in part because the worldwide protests have been multiracial, as the image of a lone white woman sitting on the sidewalk in a rural American town with a sign which reads “Black Lives Matter” illuminates.

But perhaps what is most different about this moment is that for the first time in a world governed by neoliberalism, where as Stuart Hall and Alan O’ Shea put it there is a neoliberal common sense, we are witnessing an uprising that challenges a foundational element of that common sense, in which anti-Black racism has been a glue for the American body politic.

This is an uprising of the radical imagination which demands abolishing the reproductive structures of the making of the modern world. As Stuart Hall makes clear in his work, common sense is a contested terrain. In every major uprising where elements of the dominant order have been challenged, power when it cannot defeat immediately or ignore the uprising attempts to coopt signs and symbols of the upsurge, thereby gutting them.

So the response of many American corporations has been to proclaim support for Black Lives Matter, not for the movement but to appropriate the banner turning it into a slogan. So when Amazon proclaimed on its website at the height of the protests that Black Lives Matter, it was responding to a popular upsurge it could not ignore.

Amazon’s practice was one of appropriation. One of the remarkable features of American power is its ability to quickly gobble up what begins outside of the body politic and rework it into a hegemony without fundamental changes occurring. This is one aspect of the present moment.

But there is another somewhat troubling aspect to the moment. It is this. The current Trump regime is one which can be called authoritarian populist. One core of its ideology draws extensively from the political traditions of American white settler nationalism, a nationalism in which there is not only anti-Black racism but hostility to the figure of the so-called “foreigner.”

In the current moment this is represented by the deep anti-immigration policies and statements of the ruling regime. What the Black Lives Matter movement has done is to challenge this authoritarian populist ideology. The response of the regime is to, in Trump’s phrase, Dominate. In other words, to shut down the movement in whatever way in an attempt to silence it and to retake the ideology field of battle.

That the regime to date has not been able to successful shut down the movement speaks to its power, but it does not mean that the battle is over.

We end where we began, with Du Bois and Black Reconstruction, where in 1935, he identified a form of politics he called “abolition democracy.” It was, he argued, the necessary radical political framework — if the transformation of America was going to occur after the Civil War. For Du Bois, “abolition democracy” in his words “pushed towards the dictatorship of Labor.”

By then Du Bois was in the most radical phase of his intellectual and activist life. Eighty-five years later the Black radical imagination has reworked abolition into a demand for new ways of life, dismantling the structures which inaugurated the modern world.

Fundamental change may not come and at the time of writing this piece, things can be said to be flux and for sure a revolution is not around the corner.

But historically, fundamental change requires the work of the radical imagination, the thinking that a new form of human life is possible. The global Black Lives Matter protests have opened that space. That is its remarkable significance for the current moment.

September-October 2020, ATC 208