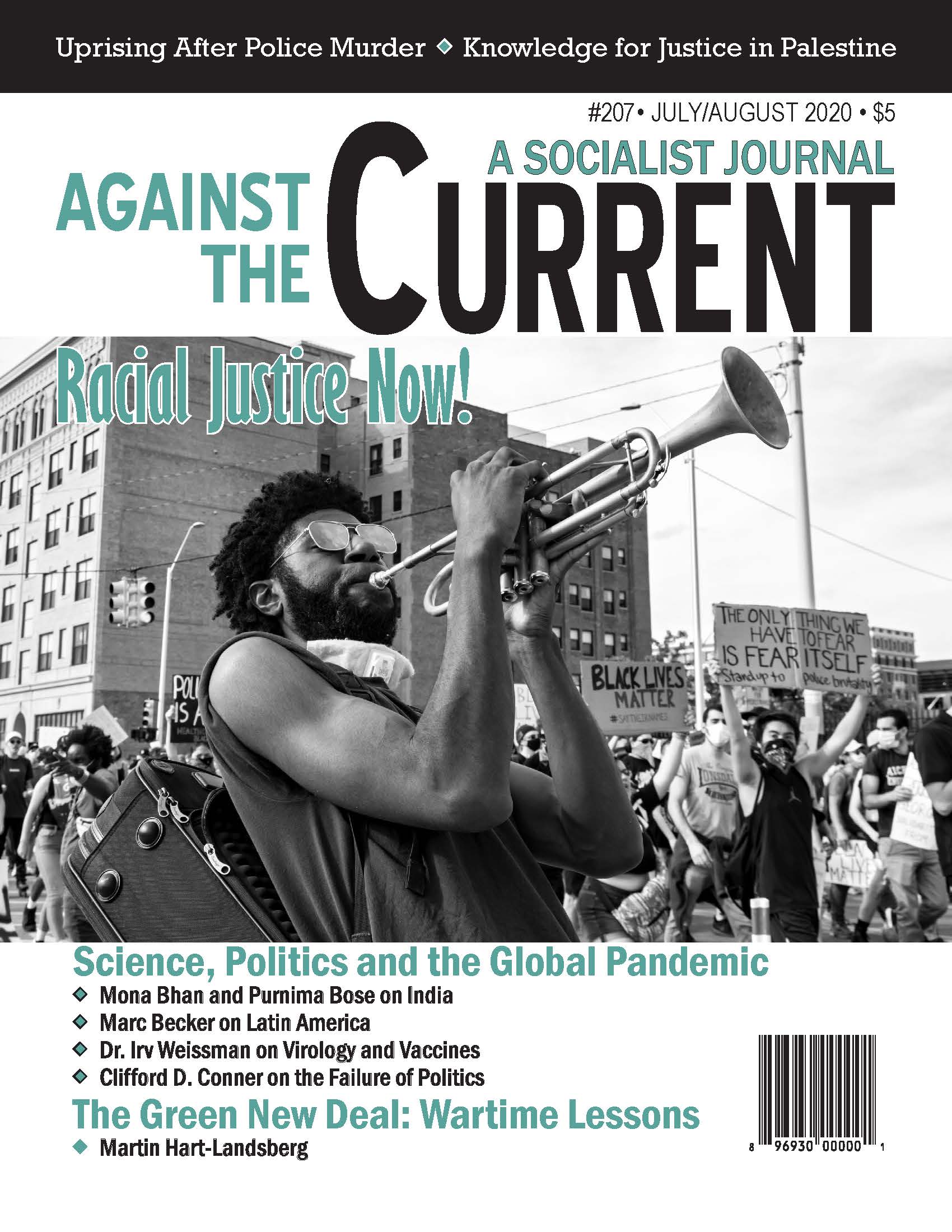

Against the Current, No. 207, July/August 2020

-

"Normal" No More

— The Editors -

U.S. Erupts with Mass Protests

— Malik Miah -

Producing Knowledge for Justice, Part II

— ATC interviews Rabab Abdulhadi -

Lessons from World War II: The Green New Deal & the State

— Martin Hart-Landsberg -

White Supremacy Symbols Falling

— Malik Miah -

The Brotherhood of Railway Clerks

— Jessica Jopp - The Pandemic

-

Authoritarianism & Lockdown Time in Occupied Kashmir and India

— Mona Bhan & Purnima Bose -

Ending the Lockdown?

— Mona Bhan and Purnima Bose -

The Virus in Latin America

— Marc Becker -

Science, Politics and the Pandemic

— Suzi Weissman interviews Dr. Irv Weissman -

What We Need to Combat Pandemics

— Clifford D. Conner - Reviews

-

Clarence Thomas's America

— Angela D. Dillard -

Homeownership and Racial Inequality

— Dianne Feeley -

Anti-Carceral Feminism

— Lydia Pelot-Hobbs -

Half-Life of a Nuclear Disaster

— Ansar Fayyazuddin and M. V. Ramana -

Can the Damage Be Repaired?

— Bill Resnick -

A Lifetime for Liberation

— Naomi Allen

Lydia Pelot-Hobbs

All Our Trials:

Prisons, Policing and the Feminist Fight Against Violence

By Emily L. Thuma

University of Illinois Press, 2019, 246 pages, $24.95 paperback.

THE DEMAND THAT no one be caged is an old one. Decades before the U.S. prison population hit two million and the concept of “mass incarceration” entered the public lexicon, anti-racist feminist organizers called for the end of criminalization and confinement.

In the new book All Our Trials: Prisons, Policing and the Feminist Fight Against Violence, Emily Thuma traces the “history of activism by, for, and about incarcerated domestic violence survivors, criminalized rape resisters, and dissident women prisoners in the 1970s and early 1980s” (2)

Focusing on how grassroots organizations contested gendered and racial carceral violence, All Our Trials offers a vital history for contemporary prison abolitionists seeking to make the world anew. The author is assistant professor of politics, philosophy, and public affairs at the University of Washington – Tacoma.

At the heart of the book is Thuma’s examination of how everyday activism sought to win material victories against the widening net of criminalization and reframe discussion and debates on gender-based violence.

Anti-carceral feminism, as Thuma elucidates, reveals that punitive power is anchored in patriarchal approaches to safety and violence — hence the necessity of rerouting responses to state and interpersonal violence from the carceral state to the transformative potential of community-based responses rooted in care.

In tracing a multitude of abolitionist feminist projects across the United States — from campaigns to close carceral psychiatric units, to Black feminist anti-rape work, to mass defense campaigns for criminalized sexual assault survivors, to radical feminist anti-prison newsletters — Thuma highlights the breadth of this activist current. Their organizing surpassed any single strategy or tactic, reminding us that there is no silver bullet for undoing mass criminalization and the carceral state.

Thuma’s book is also notable for her thick description of not just what these various groups and coalitions organized but how they organized — from the structures of their meetings to their handling of internal political disagreements.

One of many strengths of All Our Trials is Thuma’s keen attention to how through political struggle, grassroots organizers sharpened their analysis of and produced new knowledge about the operations and logics of the carceral state.

Significantly, much of this work was led by radical women of color and anti-racist white women — many of whom identified as lesbians — who took what we would now describe as an intersectional approach to questions of gender violence.

Socialist and anti-capitalist politics also played a key role as anti-carceral feminists located the expansion of punitive state power as entwined with the contradictions of racial capitalism. In centering the experiences of criminalized and incarcerated women, this feminist formation revealed how the disciplining of racialized gender and sexuality was crucial in the production of carceral power — pushing the burgeoning prison abolitionist movement to integrate feminist politics.

At the same time, anti-prison and anti-policing feminists challenged the liberal tendencies of the mainstream feminist movement, which failed to interrogate not only how patriarchy was intertwined with other systems of oppression but also how interpersonal gender violence was situated within structures of state violence.

The abolitionist feminist organizing that Thuma details fundamentally counters the logics and practices of “carceral feminism” — the strand of feminist politics contending that the best strategy for remedying sexual violence and other forms of interpersonal gender violence is through increasing punitive state power.

In recent years, contemporary activists with organizations such as INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence have rightfully tied the rise of carceral feminism to the state’s co-optation of the early domestic violence movement through attaching funding streams to collaboration with law enforcement.

Yet Thuma reminds us that this co-optation was never totalizing. Although the collectives, organizations and coalitions she documents were never the mainstream of the feminist movement, they still provided an anti-racist, left edge to debates on dismantling patriarchal power and offered more expansive visions of liberation.

Organizing Mass Defense

Thuma begins the book by tracing a series of mass defense campaigns focused on women of color and indigenous women’s right to resist sexualized violence. The significance of the campaigns of Joan Little, Inez Garcia, Yvonne Wanrow and Dessie Woods went beyond their specific cases as they illuminated how “the struggle against the abuses of the carceral state and the struggle to eradicate sexual and domestic violence [were] indivisibly linked.” (10)

Through protests, teach-ins, and movement lawyering outside and inside prison walls, these campaigns won concrete victories, set legal precedents and reframed debates on feminist self-defense and racial criminalization.

While mass defense campaigns have a long history on the U.S. left from the Scottsboro case to Angela Davis, the 1974-1975 case of Joan Little galvanized a multi-pronged defense movement that would reverberate across the decade.

During her imprisonment at a North Carolina jail, a white guard Clarence Alligood physically forced Little to perform oral sex until she managed to stab him with the icepick he wielded against her.

The state responded to her self-defense by charging her with first degree murder with the possibility of the death penalty.

Soon the Joan Little Defense Fund organized for Little’s acquittal, Refusing to exceptionalize her story, instead they emphasized how her case was located at the nexus of the right of women to self-defense against sexual violence, the inhumanity and violence of prison conditions, and the discriminatory deployment of the death penalty against Black people and poor folks.

Thuma demonstrates that the Free Joan Little campaign became a coalitional space for Black liberation, feminist, and prisoner movements. This cross-section of organizers rooted the campaign in the long lineage of Southern activism against white supremacist gendered violence, while also expanding the left’s understanding of who constituted a “political prisoner.”

Furthermore the Defense Fund pushed against the mainstream feminist movement’s “everywoman” narrative which contended that Little, like other sexual assault survivors, represented the struggle of all women. Rather anti-racist feminists, most notably Angela Davis, argued the need to recognize how Little’s structural position as a Black incarcerated woman in the U.S. South made her particularly vulnerable to white supremacist sexual violence.

The campaign’s success in making Little the first woman acquitted of armed self-defense against a rapist proved the power of participatory defense campaigns.

The success of the Free Joan Little campaign paved the way for the defense campaigns of Inez Garcia, Yvonne Wanrow and Dessie Woods. Although different contexts shaped each of these cases and campaigns, organizers learned from and built upon each other’s struggles.

Thus Black and white feminists formed the D.C. Coalition for Joan Little and Inez Garcia (acquitted in 1977), explicitly linking the two cases through everyday activism and political rhetoric. Additionally, the National Committee to Defend Dessie Woods — formed by activists affiliated with the African People’s Socialist Party — argued that the state’s targeting of Woods was an example of the repression of Black women under racial capitalism and the internal colonization of Black people in the United States.

Their analysis resonated with the long, ultimately successful campaign to free Yvonne Wanrow — a member of the Sinixt/Arrow Lakes Nation — who stressed how her criminalization was tied to settler-colonialism.

The Prison/Psychiatric State

Moreover, feminist organizers took on the inherent violence of what they termed the “prison/psychiatric state” through the Coalition to Stop Institutionalized Violence (CSIV). Decarceration, feminist, and mental patient liberation activists formed CSIV in 1975 to block the opening of a locked psychiatric facility for “violent women” in Massachusetts.

The state’s proposal was shaped by the medicalization of carceral regimes, particularly the rise of “behavior modification” units in response to prison protests. While this was framed by state officials as necessary for the treatment of mentally unstable and violent women, CSIV declared that whom the state deemed violent was fundamentally a political question.

Building from insights gleaned from previous inside/outside organizing against a similar unit, CSIV “argued that the center would be used discretionarily against imprisoned women who protested their conditions of confinement and that women of color and lesbian women would be particularly vulnerable.” (55)

Their organizing drew on queer activism that challenged the power of psychiatry to define “deviant” and “normative” gender expression and sexuality, and the pathologization of resistance to state violence. CSIV called attention to the carceral links among jails, prisons and psychiatric institutions and demanded community alternatives.

Through mass protests, petitions and political education, CSIV put the proposed unit for violent women up for public debate. Activists took advantage of the fact that the approval of the unit fell under the jurisdiction of the more left-leaning Department of Public Health, which they targeted at public meetings with testimonials — leading to the state removing the unit from the state budget.

CSIV’s victory not only stemmed carceral state expansion. As Thuma illuminates, by the coalition “reconfigure[ing] violent women as victims of institutional violence and foreground[ing] imprisoned women as subjects of feminist discourse, CSIV challenged the liberal legal imaginary in which criminals and victims were discreet populations and called for alternatives to criminal justice.” (80)

Thuma further recounts how radical women’s prison newsletters made abolitionist world-making possible across bars. She details how two publications of the 1970s — No More Cages and Through the Looking Glass: A Women and Children Prison Newsletter served as “hidden transcripts” of women’s resistance to confinement while also attacking the isolation that is critical to prison regimes.

These publications served as spaces for imprisoned activists and their outside counterparts to share information and organize around issues ranging from the criminalization of battered women, including Yvonne Wanrow and Dessie Woods, to women’s prison strikes to demands for adequate healthcare. As Thuma notes, such “print media not only documented activism; it helped to produce it.” (122)

Furthermore, by putting carceral violence against women at the center of their analysis, prison newsletters incubated a politics of abolition feminism. Prison newsletters constituted an important site of collective activist knowledge production, ranging from critiques of the erasure of women’s prisons from radical prison movements to critiques of the mainstream feminist anti-violence movement’s cozying up to the criminal justice state. These clarify the racial and gendered violence central to imprisonment.

Coalition for Women’s Safety

The final activist current that All Our Trials examines is multifaceted Black feminist antiviolence organizing in Boston and Washington, DC that advanced a critique of state violence and put forth alternatives to criminalization. Thuma charts the history of the neighborhood-based Coalition for Women’s Safety (CWS) which developed in response to the crisis of Black women being murdered in Boston during 1979.

While several organizations comprised CWS, Thuma highlights the central role played by the Combahee River Collective — the Black lesbian feminist socialist collective known for their articulation of systems of oppression as “interlocking.” Combahee’s pamphlet Why Did They Die? argued that the root of this crisis lay in the intersection of racism and sexism, including in the press and police’s neglect of the crisis.

This analysis shaped the activism of CWS, which engaged in street level political education to counter dominant narratives of the killings as random, alongside advocating for collective self-protection over calls for heightened policing. The work was to tackle the immediate crisis and to challenge “the persisting, pervasive reality of lethal and nonlethal violence against women.” (132).

In addition, their expansive vision motivated them to support the defense campaign of Willie Sanders — a local Black man who grassroots activists contended was framed for a series of high profile rapes in a white neighborhood. For CWS this work was part and parcel of their work of creating a society invested in the safety of all Black people and all women.

Adjacent to CWS’s activism, Black feminists with the DC Rape Crisis Center (RCC) expanded what was considered anti-rape work. While initially run by a collective of predominantly white feminist women — many who were rape survivors — the recruitment of working class women of color activists for paid jobs rerouted the political direction of the DC RCC.

The growth of Black feminists in organizational leadership pivoted the organization towards community accountability over criminal justice intervention in their anti-rape work — a critical position to take as more and more RCCs turned to carceral feminism. For instance, in contrast to the white radical feminist movement’s separatist politics, the DC RCC believed in the necessity of working across gender lines — notably with their collaboration with the group Prisoners Against Rape.

Moreover, their analysis translated into their broad-based anti-violence organizing, from the First National Conference on Third World Women and Violence in 1980 to their coalitional DC’s March to Stop Violence Against Women and their community organizing in the face of the shooting of their own board member Yulanda Ward.

All Our Trials is a compelling historical analysis of the varied and rich political tradition of anti-carceral feminism. Thuma provides today’s abolitionist activists with a highly usable past to learn from, as we strive to redirect our collective capacities away from prisons and policing and towards transformative justice and care.

July-August 2020, ATC 207