Against the Current, No. 205, March/April 2020

-

All the Wars: No End, No Point?

— The Editors -

Immigration: The Public Charge Rule

— Emily Pope-Obeda - Siwatu Salama-Ra Is Free!

-

Moms 4 Housing Struggle

— Isaac Harris -

Why the Right-wing Populist Upsurge?

— Val Moghadam - Notes to Readers

- The Torture of Chelsea Manning

-

The Fallacies of Geoengineering

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

Markets & Private Sector: View from the Farm

— John Vandermeer -

Trump-Netanyahu-Apartheid Plan

— David Finkel -

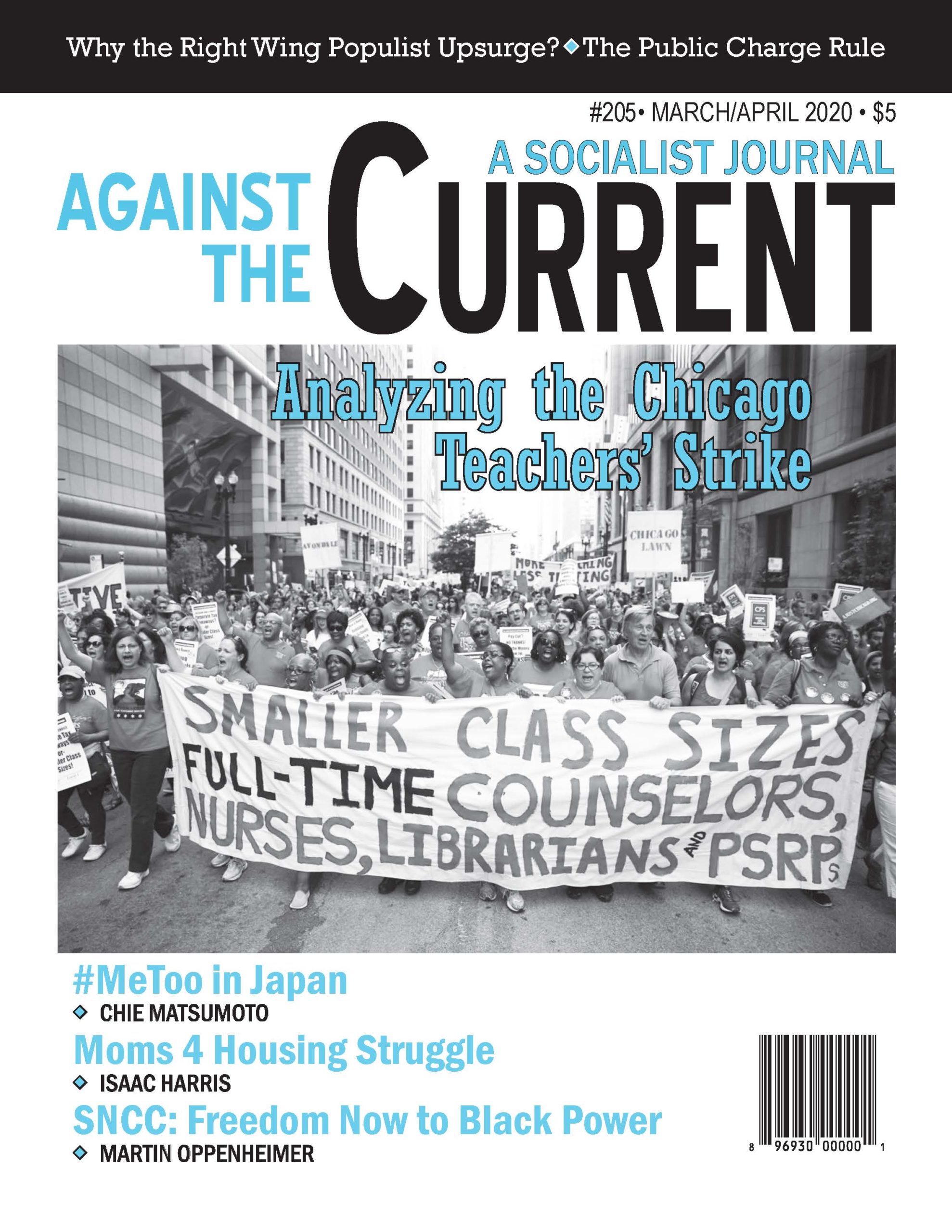

Chicago Teachers Strike, Win

— Robert Bartlett -

SNCC: Freedom Now to Black Power

— Martin Oppenheimer - Feminist Theory and Action

-

#MeToo in Japan

— Chie Matsumoto -

Looking at Social Reproduction

— Cynthia Wright - Reviews

-

Burning Questions of Our Planet

— Steve Leigh -

A Voice of Resistance Revisited

— By David Finkel -

Decaying Teeth, Decaying System

— Rachel Lee Rubin -

Escaping the Debt Trap

— Michael McCallister -

Class, Race and Elections

— Fran Shor -

Surveillance Capital & Resistance

— Peter Solenberger - In Memoriam

-

Margaret Shaper Jordan, 1942-2020

— Dianne Feeley & Johanna Parker

Fran Shor

Merge Left:

Fusing Race and Class, Winning Elections, and Saving America

By Ian Haney Lopez

The New Press, 2019, 288 pages, $27 hardcover.

THE LEFT IN the United States has historically foundered over how to develop a political strategy that recognizes all the contradictions inherent in the intersections of class and race. Early 20th century socialists, like Eugene Debs, believed that attacking the class system embedded in capitalism would, in itself, solve the “Negro Question.”

On the other hand, the Communist Party USA during its “Third Period” in the late 1920s and early 1930s, raised the slogan of “Self-Determination for the Black Belt,” not with regard to the actual wishes of African Americans (North or South) but in obeisance to the doctrine of the Communist International that dictated a nationalist line.

Ian Haney Lopez, a University of California-Berkeley law professor and author of Dog Whistle Politics (2014), in his important new book, Merge Left: Fusing Race and Class, Winning Elections, and Saving America, tries to navigate between a “class” left that continues to subordinate issues of racial justice under a banner of “economic populism,” evident at times in the Bernie Sanders campaign (141-45), and racial justice radicals who dismiss class as a determining factor in addressing the persistence of white supremacy. (98-116)

Acknowledging the co-determining role of class and race, Haney Lopez proposes a race-class approach that he believes will engender racial and economic justice.

There is much to admire and emulate in Haney’s analysis and strategy. At the same time, in his efforts to formulate a political strategy that goes beyond what he sees as the underlying “moral” arguments of racial justice advocates and downplaying of racism by the class left, Haney Lopez’s positions become problematic precisely to the extent that they focus almost exclusively on electoral politics and the reliance on a “winning” rhetorical message.

The key point, stressed by Haney Lopez and his associates who provided the polling data extensively used for his analysis and strategy, is that “most Americans — including many who do not consistently vote Republican — are susceptible to coded messages about threatening or undeserving people of color but are not consciously committed to defending white dominance.” (20)

In relying on polling data that are framed around ideological messaging for electoral campaigns, Merge Left diminishes the role of collective struggle that contests class and race rule and the identity structures that prop up racial resentments.

On the other hand, Haney Lopez’s analysis provides much insight into how racial resentments are mobilized by politicians, especially with what he calls, following George Lakoff, “core narratives.” Those narratives, which work to reinforce the rule of a white oligarchy, are: “1. Fear and resent people of color; 2. Distrust government; 3. Trust the marketplace.” (73)

Yet Merge Left never provides a thorough analysis of the neoliberal context for the later two core narratives, a context that would do much to anchor those narratives in the social and economic conditions of the times.

Politics of “White Fragility”

Certainly, Haney Lopez acknowledges how the policies and positions adopted by the Reagan and Clinton Administrations reinforced, to differing degrees, these core narratives. His ability to reveal how dog whistle politics inflamed racial resentments and played upon what Robin D’Angelo has labeled “white fragility” is exemplary.

In addition, his analysis of how Trump “epitomizes the connection between white racial spite and widespread economic ruination” (220) offers the historical opportunity for contesting the ugly remnants and resonances of white supremacy.

However, there is a lack of understanding of how deeply rooted connections among national identity, citizenship and whiteness informs a white identity politics that appears impervious to the kind of cross-racial solidarity that Haney Lopez champions.

In other words, race and class are also confounded by the constraints and contradictions of nationalism and imperialism.

On the other hand, the book helps to make very clear how “racial resentment and economic hardship exist in a mutually reinforcing relationship.” (140) Linking this to the vicious feedback loop of racial resentment and class rule, Merge Left skewers those politicians and their economic masters in the following insightful manner:

“Racial resentment helped build enthusiasm for dog whistle politicians, who then did favors for the economic royalty, which caused economic misery, which set the conditions for more racial scapegoating, which built more support for dog whistle politics serving the interests of plutocracy, more wealth being siphoned skyward, more scapegoating, and down the country slumped.” (140)

To break this vicious cycle and to win over electorally those “persuadables,” whom Haney Lopez contends are not wedded to white dominance, it is incumbent upon those on the left to find the right messaging. This messaging, which is provided by examples throughout the book, balances the class-race arguments, not tipping too far in either the class or race direction but always framing the message of how race is used to increase class depredations.

The Power of Struggle

While Merge Left pays homage to collective struggle outside the electoral arena, the commitment to messaging that relies on a finely tuned electoral discourse undercuts the important role of collective struggle in breaking the class-race negative nexus.

There are myriad examples of how multi-racial collective struggles can create real breakthroughs and establish solidarity. One example is from Studs Terkel’s Working, where a former KKK member becomes a union activist in a local dominated by Black women. In the process of striking and building their solidarity, the racist scales falls from the eyes of this white union activist.

Alternatively, Haney Lopez could have more fully explicated these passages from the excerpt he cites in Keenga-Yamahta Taylor’s compelling book From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation:

“Solidarity is only possible through relentless struggle to win white workers to antiracism…to win the white working class to the understanding that, unless they struggle, they too will continue to live lives of poverty and frustration, even if those lives are somewhat better than the lives led by Black workers.” (Taylor, 215; Quoted by Haney Lopez, 181)

Without constant reinforcement and creation of real solidaristic environments, calling for class-based cross-racial solidarity through race-class messaging in electoral campaigns will most likely never achieve the transformative politics that Merge Left advocates. Nevertheless, as Haney Lopez reminds us, we cannot afford to neglect either class or race (or gender for that matter) as critical co-determining factors in how we build a multi-class and multi-racial solidarity.

March-April 2020, ATC 205