Against the Current, No. 204, January/February 2020

-

Hope in the Streets, continued

— The Editors -

On the Coup in Bolivia

— Bret Gustafson -

Canada's 2019 Election

— Paul Kellogg - Students in Pakistan

-

Introduction to H. Chandler Davis

— Alan Wald -

Speaking Up in Ann Arbor

— H. Chandler Davis -

Beyond the 2019 UAW Negotiations

— Dianne Feeley -

100 Years of U.S. Communism

— Alan Wald -

Introduction to Socialist Perspectives on the 2020 Elections

— The Editors -

Socialists and the 2020 Election

— Linda Thompson and Steve Bloom - Black History

-

How Race Made the Opioid Crisis

— Donna Murch -

The Pursuit of Truth in the Delta

— Paul Ortiz -

1919 Elaine Massacre

— Paul Ortiz -

Discrimination in the Delta

— Julian C. Valdivia -

A Freedom Odyssey

— Omar Sanchez -

Introduction to Richard Wright's Forgotten Speech

— Scott McLemee -

Such Is Our Challenge

— Richard Wright -

"Not racist" vs. "Antiracist"

— Malik Miah -

A Chronicle of Struggle

— Derrick Morrison -

Justice Denied

— John Woodford - Reviews

-

Latin America's Caldron

— Folko Mueller -

Syria's Unfinished Revolution

— Ashley Smith -

The Power of Gulf Capitalism

— Kit Wainer -

Lawyers of the Left

— Barry Sheppard

Paul Ortiz

THE SAMUEL PROCTOR Oral History Program embarked on our twelfth annual Mississippi Freedom Project (MFP) field work trip this summer. I have been taking University of Florida (UF) students to the Delta and other counties of the Deep South to interview civil rights movement veterans since 2008.

MFP originally focused on learning from local people and civil rights activists who were involved with Freedom Summer in 1964. Increasingly, however, we have worked with Black History tour operators and museum curators, labor unionists, immigrant rights activists, educators and others who strive to use the lessons of the Black Freedom Struggle to infuse civic engagement and organizing in the Deep South.

Teams of graduate and undergraduate students pose an array of questions to narrators on topics such as voting rights and voter suppression, equity in education, re-segregation, systemic racism, mass incarceration, and democracy in their interviews. In turn, these questions inform the students’ senior thesis essays, activism and career trajectories.

Our students have interviewed rank-and-file organizers of the 1956 Tallahassee Bus Boycott, founders of the Deacons for Defense and Justice in Louisiana, members of the Mississippi Immigrant Rights Alliance and many other organizations.

In addition to gathering and preserving stories of how social change occurs, students have applied these historical narratives to chart pathways into becoming immigration and civil rights attorneys, historians labor organizers, and activists with Black Lives Matter organizations among many other important vocations and avocations.

Retrieving Hidden Histories

I began doing oral history field work in Florida as well as rural Mississippi and Arkansas counties when I was a graduate student at Duke University in 1994. Graduate student research teams conducted interviews with African American elders as part of the “Behind the Veil: Documenting African American Life in the Jim Crow South,” project sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities. One of the outcomes of this field work is the book Remembering Jim Crow: African Americans Tell about Life in the Segregated South.

As a former organizer with the United Farm Workers of Washington State, the experience of doing oral histories in the rural South taught me anew about the intergenerational and often hidden histories of organizing which were the foundation of the modern civil rights movement.

Interviews in the Florida panhandle guided me to archival sources which allowed me to write the story of how African Americans launched a frontal assault against white supremacy in the guise of a statewide voter registration movement after World War I.

During the Behind the Veil interviews conducted in the mid-1990s, we learned from courageous individuals who witnessed anti-Black pogroms and who survived lynching attempts.

I was able to chronicle stories of generations of African American organizers, including coal miners who became organizers of the Congress of Industrial Organizations as well as founding members of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Congress of Racial Equality in Florida.

During the 12-year history of the Mississippi Freedom Project, I have been able to introduce students to the children as well as grandchildren of some the original narrators who taught me a new understanding of American history that I still do not encounter in the history textbooks. We have conducted over 250 oral history interviews, many of which are now accessible to the public via University of Florida’s Digital collections.

Our Journey Into History

We pile into two vans at 6:00 am on a Sunday morning in August to begin an over 1200-mile odyssey that will bring us face-to-face with deep historical realities that no one can possibly confront alone.

Of equal importance to the encounters with local people and movement veterans are the long van rides between towns that allow students to discuss with each other what they’ve learned and why their lives will never be the same again.

This week-long fieldwork trip does not charge tuition or fees, and it provides opportunities for students to form a personal relationship with individuals and groups whose civil rights work changed the course of American history. The Proctor Program raises funds for the entire cost of the trip so there is minimal expense to the students.

In return, we ask a lot of our students. Most days begin before first light. While the students’ primary objective is to conduct interviews, they also perform required readings, attend training and orientation, facilitate public programs during the trip, attend workshops, sing freedom songs, write reflections, transcribe interviews, and engage in evening discussions on the challenging topics of the day.

The trip is funded by generous donors who make it possible for us to take students to do oral histories in Vicksburg and Natchez as well as Bogalusa, Louisiana. In addition, our students typically go on tours of the Emmett Till Museum in Glendora, Mississippi and the Equal Justice Initiative’s “Slavery to Mass Incarceration” Museum and National Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama.

We combine interviews with days of service. This year’s service days include a day of pulling weeds and lawn care in the “Colored Cemetery” in Natchez as well as informal “Getting to College” rap sessions with high school youth in several towns along the way.

Elaine, Arkansas

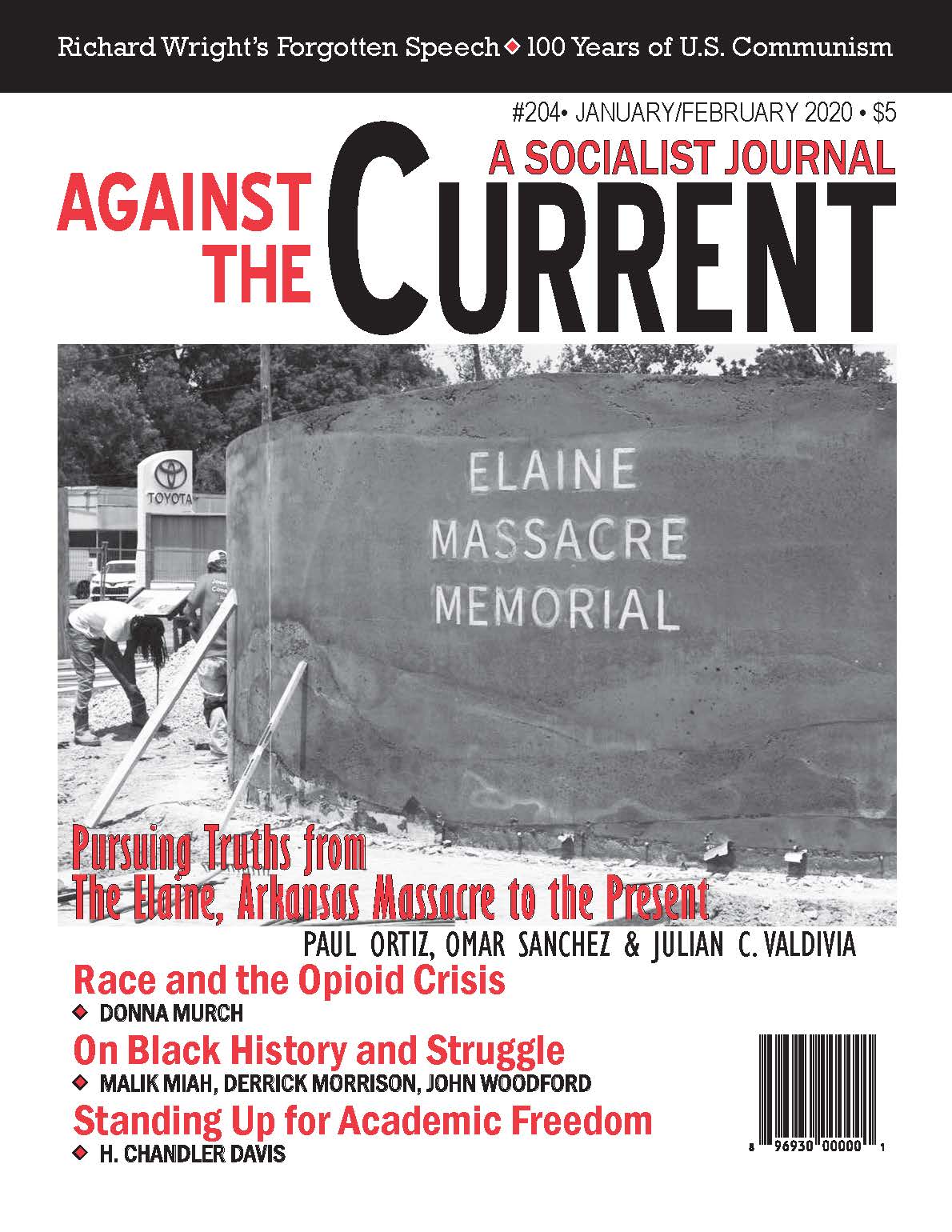

This year the Proctor Program was invited by Mary Olson and the Elaine Legacy Center to Elaine, Arkansas in order to help commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Elaine Massacre. In 1919, white elites and federal troops carried out a pogrom and mass murder of over 300 Black farmers in order to steal African American land and crush working-class self-activity.

I have given testimony for the Elaine Truth Telling Commission, and was very excited to be able to introduce UF students to a group of courageous historians and community members from Phillips County who are working for racial truth and reconciliation in the Arkansas Delta.

I have studied and taught about the Elaine Massacre on many occasions as a university professor. I never dreamed, however, that the Proctor Program would be invited to the Arkansas Delta to help try to understand the terrible and triumphant legacies of this cataclysmic event.

Understanding the profound racial wealth disparities in the United States and the importance of the struggle for reparations means coming to grips with anti-Black pogroms like the Elaine Massacre, where plantation owners and developers disenfranchised and expropriated thousands of acres of land from African American farmers and workers in Phillips County.

At the Elaine Legacy Center, I facilitated a discussion workshop among approximately 30 community members and visitors about what reparations might entail, while our students conducted interviews with descendants of the victims of the massacre.

During this workshop, Mr. William Quiney III took a group of UF students to the Elaine Willow Memorial, which symbolizes the lives lost during the massacre and captured what turned out to be the last video of the memorial before vandals destroyed it later that summer. The destruction of historical markers in Elaine as well as at the Emmett Till trail remind us that history is no longer an elective but a matter of life and death.

The Elaine Legacy Center reminds us that there are also positive legacies of 1919, and that the courage and resilience of African Americans in the Arkansas Delta truly makes Elaine “The Motherland of the Civil Rights Movement.” The discussions we had during that amazing August day in Elaine were the widest-ranging and most powerful dialogs I’ve ever participated in on the topic of reparations.

In the Delta, the reparations debate is not an abstract rumination on white guilt and “past discrimination.” It is a vital discussion centering on generations of ongoing, anti-Black racism, land loss, white supremacist violence and federal malfeasance in the allocation of resources in rural counties.

Enduring Impacts of Oral History

Part of the enduring impact of the MFP trip is the way in which oral history encounters create bonds of solidarity between field researchers and the people they talk with and learn from. Many of our students continue to stay in contact with Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee veterans, and other activists they’ve met during summers in the Delta.

Another consequence of meaningful field work is that by venturing far outside of one’s comfort zone, students are often able to break through the myth of “American Exceptionalism.” This myth prevents most Americans from seeing their nation as anything other than a model republic that needs at most minor reforms. One former MFP student, now a practicing attorney working in civil rights and immigration law reflected on her experiences in 2011:

“I have always been global-minded — concerned with the welfare of all peoples, being a citizen of the world, and the like. I focused on global issues…yet this trip to the Delta showed me the uglier side of our great nation, the embedded horror in the still-bloodstained South. I am determined to begin with awareness. As I said, my generation has not found its voice, its cause yet. But we cannot rest on the laurels of our forefathers, we cannot bask in their achievements, because that is not sustainable behavior. We must find our fire, our voice, and wield it fiercely. But awareness and education are the first steps. Unless my generation understands the dire state of the world we inherit, we cannot do much. I can say that the trip to the Delta has awoken the activist in me. And she will not rest until ignorance is no longer a viable excuse for inaction.”

Another student alumna of the Delta trip reflected on how living history can overcome the kind of cynicism and despair that appears to be a staple of bourgeois society today:

“Overall, these interviews and this trip has opened my eyes. Things may have changed but there’s still much to be done. The point of the Civil Rights movement was to give blacks (and Latinos, other minorities, and laborers) equal footing as their white counterparts. When you look at things like the achievement gap and the black population in our jails, it’s hard to tell how far we’ve come. And that’s what these oral history interviews have given me: a closer look at reality. It’s one thing to read a story on a page, but to be face to face with a living, breathing human who went through apartheid in this country is a completely different learning experience. You cannot simply shrug your shoulders after hearing stories of dehumanization and say things like, ‘that was a long time ago. We’re in a post-racial society now.’ These interviews animate, give life to the history of Jim Crow you read in books. These interviews made me stare my own history in the eyes and see that the fight for equality still needs to be fought.”

January-February 2020, ATC 204