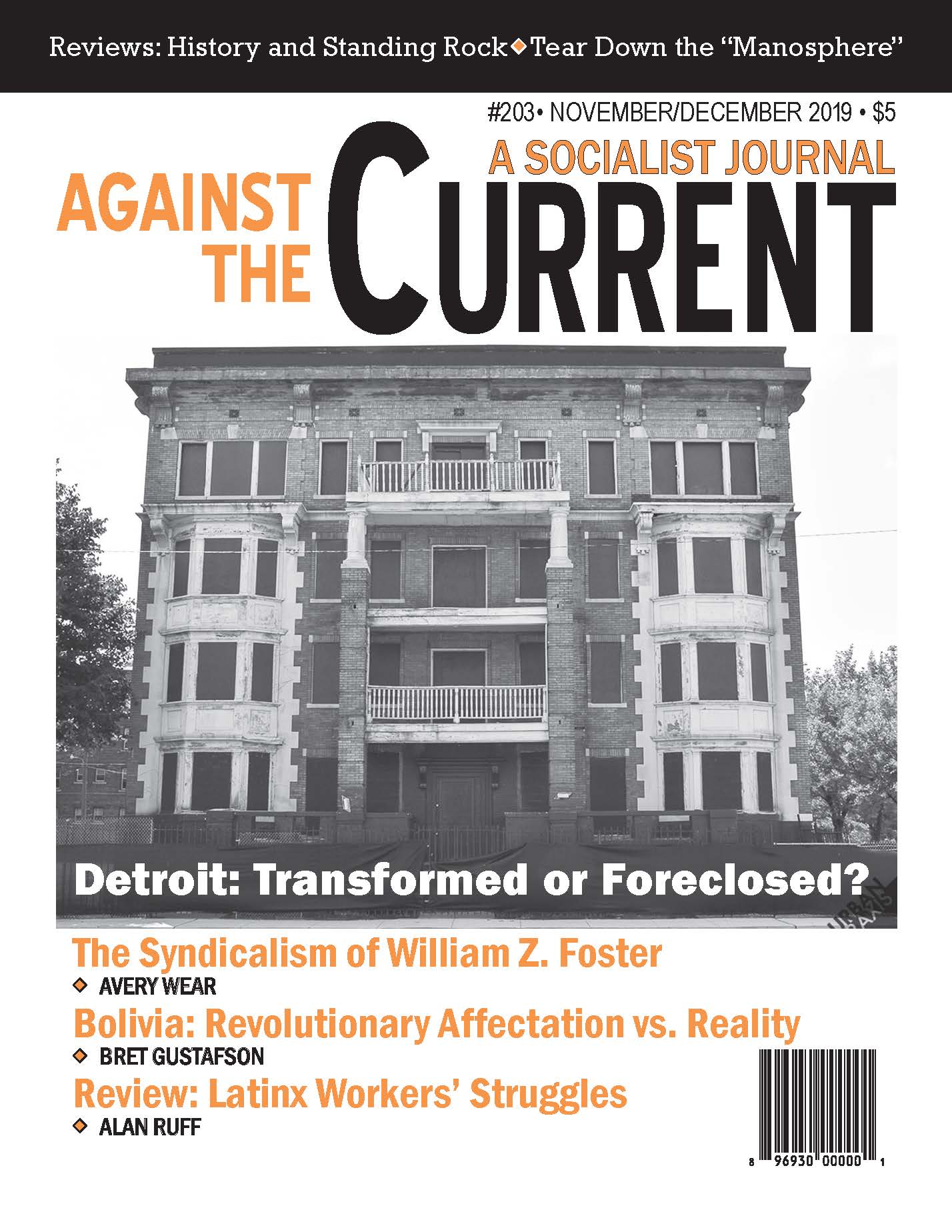

Against the Current, No. 203, November/December 2019

-

Impeachment and Imperialism

— The Editors -

Detroit Foreclosed

— Dianne Feeley -

An Overview of Detroit's Affordable Housing

— Dianne Feeley -

Thoughts on Bolivia

— Bret Gustafson -

Viewpoint: Defeating Trump

— Dave Jette -

Which Green New Deal?

— Howie Hawkins -

Howie Hawkins' Statement on Presidential Run

— Howie Hawkins - Radical Labor History

-

Introduction: William Z. Foster and Syndicalism

— The ATC Editors -

William Z. Foster and Syndicalism

— Avery Wear - Reviews

-

Voices from the "Other '60s"

— David Grosser -

New Deal Writing and Its Pains

— Nathaniel Mills -

Latinx Struggles and Today's Left

— Allen Ruff -

Tear Down the Manosphere

— Giselle Gerolami -

Turkey's Authoritarian Roots

— Daniel Johnson -

Remembering a Fighter

— Joe Stapleton -

History & the Standing Rock Saga

— Brian Ward - In Memoriam

-

In Memoriam: Hisham H. Ahmed

— Suzi Weissman -

In Memoriam: William "Buzz" Alexander

— Alan Wald

Allen Ruff

The Latino Question:

Politics, Laboring Classes and the Next Left

By Armando Ibarra, Alfredo Carlos, and Rodolfo D. Torres

Foreword by Christine Neumann-Ortiz

London: Pluto Press/Univ. of Chicago, distr., 2018, 256 pages, $27 paperback.

ASSAYING THE POLITICAL and social terrain facing Latinx workers and communities in the United States, this significant work by activist scholars Armando Ibarra, Alfredo Carlos and Rodolfo Torres comes as a critical engagement and important set of interventions.

The authors take on a range of strategic and tactical concerns for a way forward in these increasingly reactionary times, striving to reintroduce the centrality of class back into the course and direction of Latino politics.

A series of theoretical and analytical discussions made concrete by a mix of case studies drawn from interviews and oral histories, the personal stories of Latinx workers and community members, the book centers upon ways to best understand and demystify various conceptions regarding the “Latinization” or “browning” of the United States.

Too often, that diverse social and political reality has been simplistically described as an undifferentiated mass, some “slumbering giant” or “the Latino vote,” as a monolith of assumed shared interests based upon commonalities of “identity” and “culture” or ethnicity, in which class relations are given short shrift at best.

At a time of increasing inequality and social polarization alongside purposefully generated white fear based upon some conjured “Latino Threat” and parallel mounting debates on the Left regarding identity politics and class relations, the authors focus upon the material bases of exploitation and oppression as the fundamental element defining the lives of the vast majority of Latinos.

The “Latino question,” they argue, can only be understood within the historical context of the United States’ political economy, of its foreign policy and demands of capital, the international division of labor, and the widespread rending of the social fabric in Mexico and further south resulting from the neoliberal “recolonizing” of the hemisphere.

While recognizing the national and ethnic diversity of the country’s more than fifty-seven million Latinos, the work primarily focuses upon the conditions faced by Mexican-Americans who currently constitute over two-thirds of that total, including not just the U,S.-born or “naturalized,” but also cross-generational borderlands migrant workers as well as more recent legal and undocumented alike. (The next largest group, Puerto Ricans make up but nine percent of the total, followed by Cubans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans and other Central and South Americans.)

The New Demographics

The authors early on lay out some illuminating demographic descriptions of the broader Latino population as a portal for their main focus. They point to the “Latinization” of not just the Southwest, but of a number of major metropolitan areas on the cusp of becoming majority Latino. Los Angeles, we’re told, is now a majority Latino city and California has become a “minority- majority” state.

That demographic shift, the authors tell us, reflects nothing more than capitalism replenishing the ranks of the working poor as Latinos have become a growing and increasingly militant portion of the U.S. working class.

Examining the issue of migrant labor and the “immigrant question,” the book takes to task the widely held notion of “push-pull factors,” a market theory of migration which simply posits that countless individuals suddenly decide to leave their homes and loved ones in search of the “opportunity” to sell their labor elsewhere.

Countering that “rational choice” explanation, the authors argue for what they refer to as an “empire theory of migration,” the context of long historical realities of imperial penetration, domination and dependency imposed by “el Norte.”

The present period’s mass migrations cannot be understood outside that context of hegemony over Mexico and Central America, made worse by neoliberal “free trade” strategies such as NAFTA, failed promises of liberalization, direct and indirect interventions, and capital’s ongoing dispossession forcing peoples off the land, into the cities and northward.

In a quest for an “alternative Latino politics,” the authors forward the necessity a “Latino cultural political economy,” a dynamic dialectical approach to class, race and ethnicity. The authors set out to articulate the essential basis for that alternative by grounding it in the lives of that Mexican and Mexican-American working class, the majority of whom find themselves largely locked into the “economic trap” of urban and rural low wage work and limited social progress.

At the level of politics, the authors critique such conceptions as “the Latino vote” and the “sleeping giant” myth commonly used to describe some imaginary monolithic voting bloc lacking ethnic diversity or class differences. They point out that homogenized conceptions of “Latino” or “Hispanic” obscure the social and political experiences and cloud over internal class divisions and interests amidst growing inequality.

Class Analysis Central

At another level, as the authors describe it, the book stands as an attempt to rescue class analysis from the “cultural turn.” As such, it contributes to an ongoing critique of Chicano/a Studies and the contemporary “discourse” that fails to acknowledge how Latinos/as are being produced and reproduced in the struggle against capital. In doing so, it reclaims an older history of class struggle and working class politics.

The authors remind us that it has been militant, indeed radical motion from below led by class conscious and organized community-rooted Mexicano workers that has defined some of the most significant social struggles extending back decades before the United Farm Workers’ 1972 founding.

The same has been true, despite the presence of other class elements, for the more recent unprecedented nationally coordinated “Day Without Immigrants” general strike of 2006, subsequent May Day marches in places like Milwaukee, and more recent community-centered efforts nationwide in regard to DACA, demands for comprehensive immigration reform, opposition to ICE, and resistance to the ethno-class war against Latino/Chicano studies curricula and educators and more general populist xenophobia.

The authors argue that the “Great Recession” beginning in 2008 hit Latinos the hardest at all levels, but also resulted in a crisis of hegemony and authority and an increased lack of trust in the established political process. This opened new opportunities for self-organization and potentials for new social movements from below potentially soldering together new solidarities of race, ethnicity, gender and class.

Complementing the book’s analytical sections, particular chapters based upon personal histories and case studies of work and community in various parts of the country and sectors of the economy breathe life into the work.

Such chapters as one on the history and present of Mexican families and migrant work in California agriculture, one recounting the life stories of the working poor in Milwaukee where thirty-five percent of Latinos live under the poverty level, and the depiction of “Latina/o Labor in Multicultural Los Angeles” illuminate and give substance to the authors’ main arguments.

Some of that longer history is consciously laid out to dispel the myths that frame Latino working communities as “new” or “foreign.”

The book sets out to challenge the prevalent orthodoxy of a Latino identity politics that posits “self,” in the absence of material conditions, as the most important unit of analysis for understanding and explaining the complexity of social relations.

While acknowledging the important historical diversities in the broad Latino/a universe and the absolute necessity of avoiding the “analytical trap” of economic determinism or reductionism, the authors forward the essential value of Marxist categories in understanding the “new social movements” and the wider political economy in which they operate.

In their view, that “cultural turn” with its individuated “identity politics” based on race, ethnicity and gender, the retreat from class, and calls for “intersectionality” created a new orthodoxy that not only rendered capital and labor invisible but also declined to subject capitalism to nuanced and profound critique at a time of increasing social and economic disparities, inequality and stagnant wages. (181)

While laying out an explicit materialist intervention in response to the abandoning of those questions of inequity, class relations and the critique of political economy — that now often forgotten essential point of interrogation in the development of Mexican-America studies in the late1960s and early ’70s — the authors also recognize the need for “a middle ground” that recognizes the role of culture in reinforcing capitalist social relations. (180)

After all, they clearly recognize the historic and contemporary value of cultural identity and the crucial key role of cultures of resistance as an essential element of movement building. They clearly emphasize, however, that:

If Latinos are to combat the growing inequality and economic subjugation in the unrepentant economy, then their response must be based not on individualist or self-focused analyses but rather on a collective and solidarity-based understanding of their position within the economic power structure as a class, a working class.

Toward the “Next Left”

The book’s concluding section calls for a strategic outlook that focuses upon the specific material manifestations of capitalism, not just on broad concepts like “racism” and “oppression,” but on their roots embedded in and resulting from the social relations of production.

In their conclusions regarding a “Next Left,” our authors rhetorically ask a key what-is-to-be-done question, “What can working-class Latinos achieve in the near future?” With Antonio Gramsci’s notion of a “strategic war for position” in mind, they respond:

(O)ur response is simple: Organize and find common ground with other social movements that have been for far too long divided by ideological boundaries. Organize to end the onslaught of capital and to end economic exploitation, for better wages and working conditions, for affordable and community-owned housing, and for fairer, more democratic, and more just workplaces. (183)

Importantly, the book’s portrayal of the Mexican-American working class — migrant, immigrant and U.S.-born — presents it not just as object or exploited victim but as the increasingly organized collective subject-in-formation.

In important ways, the work suggests that this layer is in the process of becoming an exemplary leading edge of multi-leveled resistance and “fight back” against neoliberalism’s punishing assaults; in some ways a leading element of “a class for itself.”

The book actually is about a “slumbering giant” — not in the narrow electoral sense but rather as a social mass increasingly moved to collective action by incessant exploitation and dispossession, reactionary immigration policies, and racist discrimination, alongside people’s increasing consciousness of their power that comes from organized direct action.

A rich study of the transformative nature and potential of a class-based Latino politics from the bottom up, the book should be deeply plumbed not just by those most immediately affected, but by the broader Left. The authors’ hope and this reviewer’s as well is that it reaches all those seeking perspectives that will inform today’s popular struggles to reshape the course and direction of our history.

November-December 2019, ATC 203