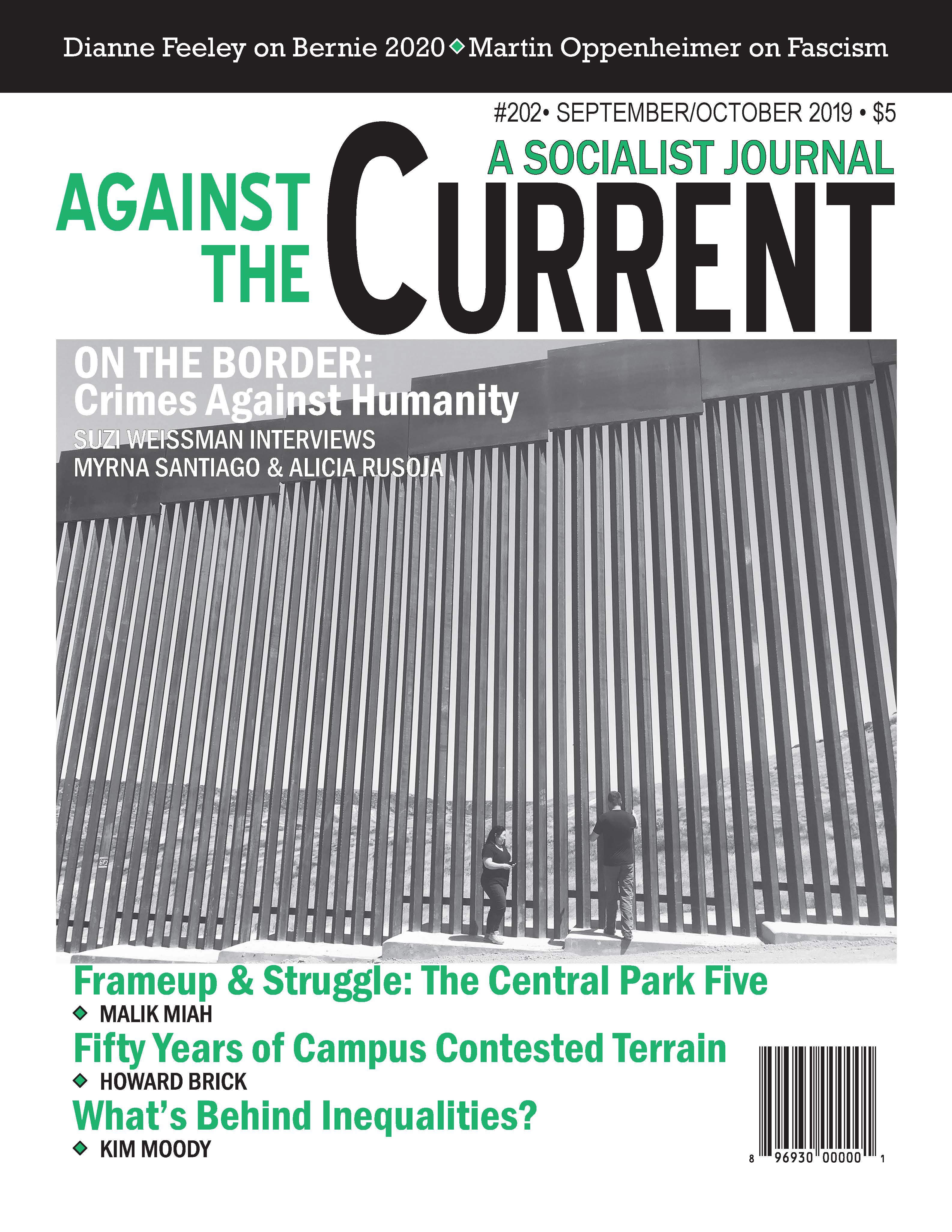

Against the Current, No. 202, September/October 2019

-

Hope Is in the Streets

— The Editors -

Talking to Those on the Border

— Suzi Weissman interviews Myrna Santiago & Alicia Rusoja -

What the Sanders' Campaign Opens

— Dianne Feeley -

Making the Master Race Great Again

— Steven Carr -

The Central Park Five Frameup

— Malik Miah -

Algerian Feminists Organize

— Margaux Wartelle interviews Wissem Zizi -

Palestine: Imperative for Action

— Bill V. Mullen -

The Crisis of British Politics

— Suzi Weissman interviews Daniel Finn - Siwatu Salama-Ra Conviction Overturned

-

Contested Terrains on Campus

— Howard Brick - Reviews

-

Competition, Inequality & Class Struggle

— Kim Moody -

Learning Through Struggle

— Marian Swerdlow -

What Is Working-Class Literature?

— Matthew Beeber -

A Debate That Never Ends

— Steve Downs -

Fascism--What Is It Anyway?

— Martin Oppenheimer -

Bolivia's Legacy of Resistance

— Marc Becker -

China: From Peasants to Workers

— Promise Li - In Memoriam

-

In Memoriam: James Cockcroft, 1935-2019

— Patrick M. Quinn

Matthew Beeber

A History of American Working-Class Literature

Nicholas Coles and Paul Lauter, editors Cambridge University Press, 2017,

504 pages, $105 hardcover.

ON APRIL 26, 1935 proletarian author Edwin Seaver addressed the American Writers’ Congress, assembled in New York City’s Mecca Temple. The topic of his speech was the fiercely debated definition of the term “proletarian literature.”

Seaver spoke of the need to “eliminate the sorry confusion that has prevailed and still does prevail [when one] assumes that a proletarian novel must be written by a worker, or must be about workers, or must be written especially for workers.”(1)

Ultimately, according to Seaver, “it is not the class origin of the writer which is the determining factor,” nor necessarily the author’s choice of subject matter, but rather “his present class loyalties.”(2) Thus, proletarian literature is not limited to writing by working-class authors, nor to writing about workers, nor to writing produced for a working-class audience. The category could include any of this work, so long as the author is “on the side of” the proletariat.

The literary critic Kenneth Burke, speaking at the same congress, came to a similar conclusion. He considered the concept of the proletariat to be symbolic and, somewhat mystically, to denote a “secondary order of reality,” transcending such mundane concerns such as class position, subject matter, or intended audience. Both Burke and Seaver, along with many leaders of the proletarian literature movement of the 1930s, thus advocated for the broadest possible parameters of the term.

A History of American Working-Class Literature, edited by Nicholas Coles and Paul Lauter, demonstrates that debates around the definition of proletarian literature are experiencing a resurgence in the 2010s. As a decade following a major economic crisis — with far-right authoritarianism and vicious racism on the rise internationally, when wealth disparity is at a record high and rising, when political camps are increasingly polarized — the 2010s make a seductive analog to the 1930s.

Indeed, although the term proletarian may have subsequently gone out of vogue (for reasons this review will address), the question at the forefront of the 1935 Writers’ Congress is being asked today in strikingly similar language.

On the first page of their introduction, Coles and Lauter report being asked: “What do you mean, ‘working-class literature?’ Are you talking about writing produced by working-class people? Writing about working-class men and women? Writing directed at a working-class audience?”

Coles and Lauter answer these questions in the tradition of Burke and Seaver, responding simply, “yes.” The volume, a collection of academic essays, makes good on this response: it conceives of working-class literature in the broadest possible terms, including critical essays on works and authors whom we may not always associate with the working class.

Transhistorical Approach

It is no accident that the volume uses the term working-class in place of proletarian; the first several essays of the collection address literature written before Marx popularized the word and with little resemblance to the Marxist-inspired literature of the 1930s. Spanning historical periods from the American colonies to the deindustrialized present, the volume takes a transhistorical approach to the concept of labor and the working class.

On the early end, co-editor Paul Lauter offers a wide-ranging discussion of the very concept of labor in his essay “Why Work? Early American Theories and Practices,” and Peter Riley emphasizes the role of labor in Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Through the course of 24 essays, the collection winds its way from the colonial period through the 18th, 19th, 20th and 21st centuries, concluding with essays such as Joseph Entin’s on “Contemporary Working-Class Literature.”

Sherry Lee Linkon’s discussion of “Working-Class Literature after Deindustrialization” in some ways frames the position of the collection as a whole, questioning — as first posited by E.P. Thompson in The Making of the English Working Class — the association between the working class and industrialization.

In severing this association we are freed to address the literature of “the next generation, working-class people for whom industrial work has never been an option,” as well as writing by and about workers which predates the industrial revolution.

The stakes of this intervention go beyond academic questions of periodization. By extending the temporal boundaries of “working-class literature” beyond those of industrialization, the volume prevents “working-class literature” from becoming a purely historical designation, tied to the mills and factories of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The volume also does significant work in expanding the boundaries of working-class literature to include writing by a diverse set of authors, including women and African Americans, both groups too often left out of traditional accounts of proletarian literature.

Following the lead of proletarian literature scholar Paula Rabinowitz, and riffing on the title of Michael Gold’s famous 1929 essay, Michelle Tokarczyk offers an account of some female authors in her essay, “Go Left, Young Women,” where she rightfully asserts the importance of writers such as Meridel Le Seuer, Muriel Rukeyser, and Tillie Olsen.

Yet again Coles and Lauter’s volume de-centers the canonical authors of 1930s proletarian literature by including essays such as Christopher Hager’s account of the “Lowell Mill Girls” and other women’s writing in the early 19th century.

And although Bill V. Mullen takes the title of his essay “I Have Seen Black Hands” from Richard Wright’s canonical 1934 proletarian poem, the piece convincingly argues that such work belongs to a continuum of Black working-class literature, spanning from slave narratives to the literature of Black Lives Matter.

As a whole, the volume extends the boundaries of working-class writing not only along a temporal axis, but along the axes of race and gender as well, a project emphasized by the final essay of the anthology, Sara Appel’s discussion of “The Place of Class in Intersectional Analysis.” However, despite its valuable work in this direction, it could perhaps be wished that such a compendium would include discussion of the rich histories of working-class literature by Asian American and Latinx authors, a notable lacuna within the collection.

Broadening the Inquiry

In addition to its inclusivity in terms of time-period, race, and gender, the collection also takes a broad stance in regard to genre. Thus the volume not only interrogates our understanding of what works are considered working class, but also what are considered literature.

Not limited to the realm of poetry and prose, the collection delves into the fields of drama, music, and film in essays such as Amy Brady’s work on “The Worker’s Theatre of the Twentieth Century,” Richard Flacks’ discussion of “The American Labor Song Tradition,” and Kathy M. Newman’s treatment of “Class Struggle and the Silver Screen.”

Even within the world of prose, the collection does not shy away from a discussion of “genre” writing, as evidenced by Nicholas Coles’ essay on “Love and Labor in Farm Fiction,” Alicia Williamson’s on “Marriage Plots in Socialist Fiction,” and James V. Cantano’s work on “Utopian and Dystopian Fiction.”

One of the most important ways in which the volume extends received boundaries of working-class literature is to give significant attention to writing which addresses various forms of forced or coerced labor. Several of the essays rightfully position slavery as an institution of labor, and the writing produced by slaves as thus working-class literature.

John March, for example, locates the “Shadow of Slavery in Nineteenth-Century Poetry and Song,” whereas John Ernest addresses “Early African-American Expressive Culture” by both enslaved and free Black writers.

Matthew Pether’s essay, on the other hand, engages with “Transportation Narratives” written by early British immigrants to the American Colonies who labored under various non-voluntary conditions. Joe Lockard extends the issue of un-free labor into the present with his analysis of “Prison Literature from the Early Republic to Attica.”

The inclusion of these essays does valuable work in reframing our conception of the working classes necessarily to include the long history of enslaved and indentured laborers in the United States.

Then and Now

In 1935, the same year that Burke and Seaver addressed the American Writers’ Congress, International Publishers released the landmark anthology Proletarian Literature in the United States.

In a 1936 review of the anthology, Burke suggests that the volume is “congregational” in nature.(3) Its purpose was to bring disparate elements together; it was not merely a collection of proletarian literature, but in fact sought to contribute to the formation of the literary movement which goes by that name.

The volume was congregational in that it welcomed new members — whether middle-class fellow travelers or hardscrabble worker-writers — to the movement. By including a wide range of works by authors of various subject positions, ascribing to differing aesthetic schools, and working in diverse literary genres, the anthology embodied its congregational politics through its organization.

A History of American Working-Class Literature, although comprised of critical rather than literary writing (and appearing more than 80 years later), does very similar work. The breadth of the subject matter has the effect of inviting a wide range of art into the category of working-class literature, producing a literary formation larger and more diverse than the term proletarian literature typically evokes.

Similar to the mid-’30s, this politics of congregation will have its detractors today. As the literary Left abandoned the militancy of the early ‘30s in favor of the broad coalitions of the Popular Front, there were many who resisted what they considered the “watering down” of the movement. As early as 1932, the minutes of the Chicago convention of the John Reed Clubs noted that “young worker-writers seemed to have spent most of their time in Chicago excoriating the sudden presence and prestige of fellow-travelers in the radical movement.”(4)

If the power of Coles and Lauter’s collection is that it broadens the category of working-class literature — to include pre- and post-industrial writing, work by women and minorities, cultural forms other then writing, and material which addresses un-free labor — this may also be cause for critique.

At first glance, to design a collection around the abstract concept of work (rather than, say, the proletariat) is to depoliticize it in a way which may cause discomfort to those most ardently invested in proletarian literature. And the transhistorical approach taken by the volume’s authors may strike some as too uncomfortably near to an ahistorical treatment of labor which collapses, say, 1930s strike narratives with the poetry of Whitman.

To focus on these critiques, however, would overlook the important intervention which the volume makes. Broadening the category of working-class literature, the authors extend conversations about working-class literature backwards and forwards in time, developing an historical framework capacious enough to discuss both slave narratives and post-industrial writing, allowing for the formation of new and more diverse congregations of politics writing.

Notes

- Hart, Henry, editor. American Writers’ Congress. International Publishers, 1935, 100-101.

back to text - Ibid.

back to text - Burke, Kenneth. “Symbolic War.” The Southern Review, Summer 1936, 134-147.

back to text - Lawrence F. Hanley. “Cultural Work and Class Politics: Re-reading and Remaking Proletarian Literature in the United States.” Modern Fiction Studies, 38:3 (Fall 1992): 718.

back to text

September-October 2019, ATC 202