Against the Current, No. 199, March/April 2019

-

Whose "Security" -- and for What?

— The Editors -

MLK in Memphis, 1968

— Malik Miah -

California Burning, PG&E Bankrupt

— Barri Boone -

PG&E Bankruptcy

— Barri Boone -

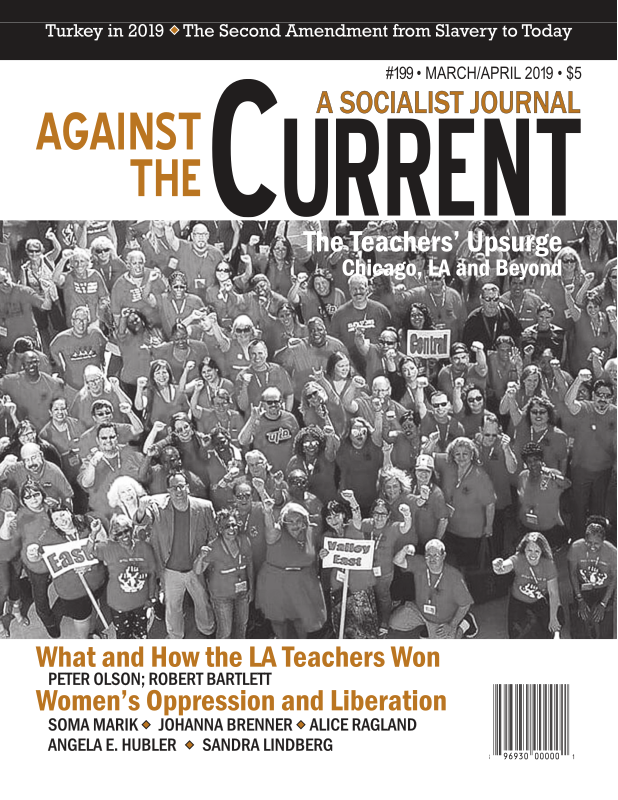

What Los Angeles Teachers Won

— Peter Olson -

The UTLA Victory in Context

— Robert Bartlett -

Chicago Charter Teachers Strike, Win

— Robert Bartlett -

Turkey in 2019: An Assessment

— Yaşar Boran -

Betraying the Kurds

— David Finkel -

The Strange Career of the Second Amendment, Part II

— Jennifer Jopp -

Who Is Responsible?

— David Finkel -

A Note of Thanks

— The Editors - Socialist Feminism Today

-

Women's Oppression and Liberation

— Soma Marik -

Marx for Today: A Socialist-Feminist Reading

— Johanna Brenner -

Angela Davis: Relevant as Ever After Thirty Years

— Alice Ragland -

The Activism of Angela Davis

— David Finkel -

White Women and White Power

— Angela E. Hubler -

Lots of Scurrying But No Revolution in Sight

— Sandra Lindberg - Reviews

-

A Call to Action

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Orbán: Strong Man, Authoritarian Ideology

— Victor Nehéz -

A Sympathetic Critical Study

— Peter Solenberger -

Further Reading on the Russian Revolution

— Peter Solenberger

Angela E. Hubler

Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and the Politics of White Supremacy

By Elizabeth Gillespie McRae

New York: Oxford University Press, 240 pages, $34.95, hardback.

Bring the War Home:

The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America

By Kathleen Belew

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 239 pages, $29.95, hardback.

DECADES AGO, IN my capacity as director of Women’s Studies at Kansas State University, I received an anonymous, xeroxed letter in which our program was accused of encouraging “Negro men” to dance with “white women.” Sickened, my academic proclivity to document and preserve was overcome by revulsion, and I threw the letter in the garbage.

At the time, I naively thought the letter seemed anachronistic, a throwback to an era about which my grandmother told me, when a 1920s Nebraska church service she was attending was interrupted by white-robed Ku Klux Klansmen sweeping in to contribute to a building fund.

Soon after I received that letter, however, about 30 minutes from the university and close to Ft. Riley, where they had been stationed before their deployment in the First Gulf War, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols assembled the bomb that killed 168 people when it exploded in 1995 at the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City.

This event, the largest act of domestic terrorism in the United States, connects to the Klan members about which my grandmother told me, the letter I received, and the recent upsurge in racist violence in the United States. These events represent efforts to maintain white, heterosexual, male power in the face of hard-won victories by civil rights, feminist, LGBTQ and labor activists.

Recent histories of racism in the 20th century by Elizabeth McRae and Kathleen Belew deepen our understanding of this violence. While they focus on different periods and distinct (though connected and overlapping) movements, both stress that the strategies and ideologies employed by the white supremacist and white power organizations have moved from southern segregationists and the radical right into the mainstream.

Both histories, then, are invaluable to understanding our current political moment. McRae focuses on the 1920s to 1970s, documenting the role of white women in “grassroots resistance to racial equality.” (4)

While the role of Black and white women in the civil rights movement has been documented, scant attention has been accorded to white Southern women’s role in preserving segregation. This omission has obscured, McRae argues, their connections to white conservative women’s political activism nationwide and their role in the development of supposedly “color-blind conservatism,” which stresses “property rights, law and order, good motherhood, and constitutional intent.”

This new language supplied the “wolf” of old-fashioned, explicitly racist politics with sheep’s clothing, and thus “disguised policies supporting racial inequality.” (10)

White Supremacist Maternalism

White segregationist women asserted a “white supremacist maternalism,” demanding segregation as a parental right based on the claim that because integration “eroded their ability to secure the benefits of white supremacy for their children it compromised their ability to be good mothers.” (14)

McRae persuasively argues that while the explicitly racist language of the early 20th century gave way in the anti-busing movement in Boston and elsewhere (to which she devotes a chapter), to demands for parental choice and control over children’s education, property rights and hostility to governmental intrusion, the goal of the movement was unchanged: to maintain racial segregation.

McRae organizes her historical analysis in terms of “real or perceived threats to racial segregation.” (10) In the interwar period, she says, the threat was understood to be “apathy,” a failure to grasp the constant labor needed to maintain it. This apathy should, according to segregationists, be confronted by local and state activism. (11)

The gender-specific duties of women authorized groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) early in the 20th century to censor textbooks that “were not loyal to the South” and promote those representing segregation as natural. (50) A primer on the KKK by UDC member Laura Rose was adopted as a text in Mississippi, while Black people, Black history and slavery were eliminated from textbooks.

The organization also sponsored essay contests, scholarships, and teacher training that encouraged “the celebration of Confederate heroes, reinforced the doctrine of states’ rights and minimized the role of slavery in the Civil War.” (51)

In the post-World War II era, the withdrawal of federal support for segregation provoked reactionary political activism — within and against the Democratic Party, opposition to the Supreme Court, the United Nations, and Black southern political mobilization.

First, southern Democrats broke with their party in response to the party’s domestic civil rights platform and Truman’s desegregation of the military in 1948. Truman’s justification for civil rights referred to the United Nations charter, a threat, segregationists argued, to national sovereignty.

The United Nations became a target for a number of the women that McRae focuses on: Florence Ogden, opposing the UN’s Genocide Treaty argued that it would threaten “private property, Christianity” and whites, as a minority of the world’s population. She asserted:

“A Negro, a Chinese, or a member of any racial minority, could insult you, or your daughter. Your husband might shoot him, knock him down, or cuss him out. If so he could be tried in an international court. It would also make it a crime to prevent racial intermarriage and intermarriage would destroy the white race which has brought Christianity to the world.” (148)

Disgusted with the Democratic Party’s support of labor rights and racial equality (she claimed the party had acted like “a heathen mother who throws her child to the crocodile”), Ogden campaigned for Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952, explaining in her newspaper column “Dis an’ Dat” that the failure of Democratic men to fulfill their patriarchal role in protecting white supremacy forced white Southern women to do so. (124)

Ogden’s opposition to the UN was shared by national conservative organizations, including the Daughters of the American Revolution, exemplifying McRae’s overall argument that southern segregationist women worked to link their concerns “to constitutional, patriotic, anti-communist, and anti-international crusades.” (161)

McRae notes that civil rights activism was often said to be linked, especially in the Cold War context, to communism and to the Soviet Union. For segregationist women, anti-communism was gendered: they considered themselves responsible for their children’s protection and education and sought to prevent interference from an overbearing state.

in 1960, in her award-winning essay in a contest for high school students sponsored by the Association of Citizens’ Councils of Mississippi, smiling, attractive Mary Rosalind Healy wrote, “I know that the social exposure of one race to another brings about a laxity of principles and a complacency toward differences which has but one inevitable result — racial death. Thus I must believe in the social separation of the races of mankind because I am a Christian. . . . It is up to ME as a product of the struggle of my forefathers, as a student of today, and as a parent of tomorrow to preserve my racial integrity and keep it pure.” (194, 192)

White Power As Social Movement

Kathleen Belew takes up her story roughly where McRae leaves off. She distinguishes the white power movement that is her subject from white supremacists on which McRae focuses. White power refers to “the social movement that brought together members of the Klan, militias, radical tax resisters, white separatists, neo-Nazis, and proponents of white theologies, such as Christian Identity, Odinism, and Dualism between 1975 and 1995.” (ix)

The origin of this movement, she argues, is the Vietnam War, based on a narrative of “soldiers’ betrayal by military and political leaders and the trivialization of their sacrifice.” (3) Disaffected veterans like Louis Beam, a central figure in the white power movement, created a paramilitary culture, affording them the opportunity to share military “expertise, training, and culture” in camps they established in Texas, Missouri, West Virginia, Indiana, Colorado, Alabama and numerous other states. (52)

While the Vietnam War and its cultural impact explains the most recent history of the white power movement, Belew situates the effect of the Vietnam War within a broader context, citing veterans’ key roles in founding the Klan after the Civil War, post-World War I violence and civil rights era attacks after WWII and the Korean War, including the 1963 bombing of the Birmingham church.

“Ku Klux Klan membership surges have aligned more neatly with the aftermath of war than with poverty, anti-immigration sentiment, or populism.” The Vietnam War in particular, says Belew, “intensified fear of Communism,” and this anti-communism unified previously distinct white power organizations, a new, post-1975 development. (20, 22)

While WWII veterans in the Klan who had fought Nazis in Europe objected to working with neo-Nazis, the Vietnam war reframed their shared interests. In 1979, members of the Federated Knights of the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party joined together to show Birth of a Nation in China Grove, North Carolina.

Members of the Workers Viewpoint Organization (soon renamed the Communist Workers Party) staged a rally and protest, and “stormed the community center armed with clubs.” After this confrontation, a Klansman commented, “I see a war, actual combat, eventually between the left-wing element and the right wing.” (57, 60)

The Complexity of Violence

Several months later, members of the newly united racist group shot and killed five protestors (“four white men and one black woman”) at a “Death to the Klan” rally organized by the CWP in Greensboro, NC. (55)

There is much to learn from this critically important event in the history of the white power movement, not least, the possible ramifications of a leftist activism — like that suggested by those who urge anti-racists to “Punch Nazis” — that embraces violence. Students in my social movements classes have been very engaged in considering this complex question.

Historicizing the issue with reference to this event is enormously helpful, although there are no clear answers. One need not be a pacifist to question the advocacy of violence when that violence ratifies the right’s sense that they are under attack, justifying yet further violence.

Of course, the debate about the use of violence is one of many factors that fragmented the left (cf. the division in the civil right movement represented by the opposition between the pacifist Martin Luther King and the militant Malcom X), at the same moment that, as Belew observes, the right was unifying.

Belew devotes a chapter to “spectacular” state violence that intensified fears within the white power movement. This militarized violence was manifested in assaults on the white separatist Weaver family on Ruby Ridge, Idaho in 1992, killing Vicki Weaver and her 14-year-old son; and the 1993 siege and assault by the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms on the Branch Davidians’ paramilitary commune in Waco, Texas, ending in a fiery apocalypse and the death of 76 members of the commune, including 21 children, and several federal agents.

These events were seen as exemplifying a violent “New World Order” that resulted in a surge in paramilitary white power organizations like the 12,000 member Michigan Militia with which Timothy McVeigh was associated.

McVeigh’s April 19, 1995 bombing of the Murrah Federal Building is a terrifying example of a defining characteristic of the white power movement: while earlier white supremacist violence “often worked to reinforce state power” the violence embraced by white power seeks to overthrow it.(x)

In 1983, says Belew, the movement had declared war on the state, at the same time that they adopted a strategy of leaderless resistance. This strategy, Belew argues, has obscured an accurate understanding of the movement and underlies mischaracterizations by the press of perpetrators of right wing violence as “lone wol[ves],” isolated “madmen” acting alone. (127)

Roots of the Alt-Right

A shift in the late 1990s to “online spaces” has further hidden the white power movement from public view, now seen, says Belew, in the “explosion” of alt-right views into the mainstream during the Trump campaign. McRae and Belew afford us a much deeper understanding of the roots of this phenomenon.

In particular, the detailed understanding of the role that white women have played in the history given us by McRae and Belew must instruct feminist practice.

Both forcefully demonstrate the way in which the sexually vulnerable figure of the white woman, threatened by Black and immigrant men, is central to the rhetoric of survival of the white race.

But the bodies of women have not been just symbolically powerful: women’s grassroots activism has also been central to the function of both the segregationist and white power movements. Thus, to treat all women as a political group with shared values and goals is deeply problematic.

This is not a new insight of course, and although women of color activists and theorists have been arguing this point for a very long time, the multiple divisions that fracture women as a group continue to trouble activism, as demonstrated by the conflicts surrounding the Women’s March.

McRae and Belew’s scholarship offers no easy answers to this problem or others they address, only information that we must consider as we continue to work toward solutions.

March-April 2019, ATC 199