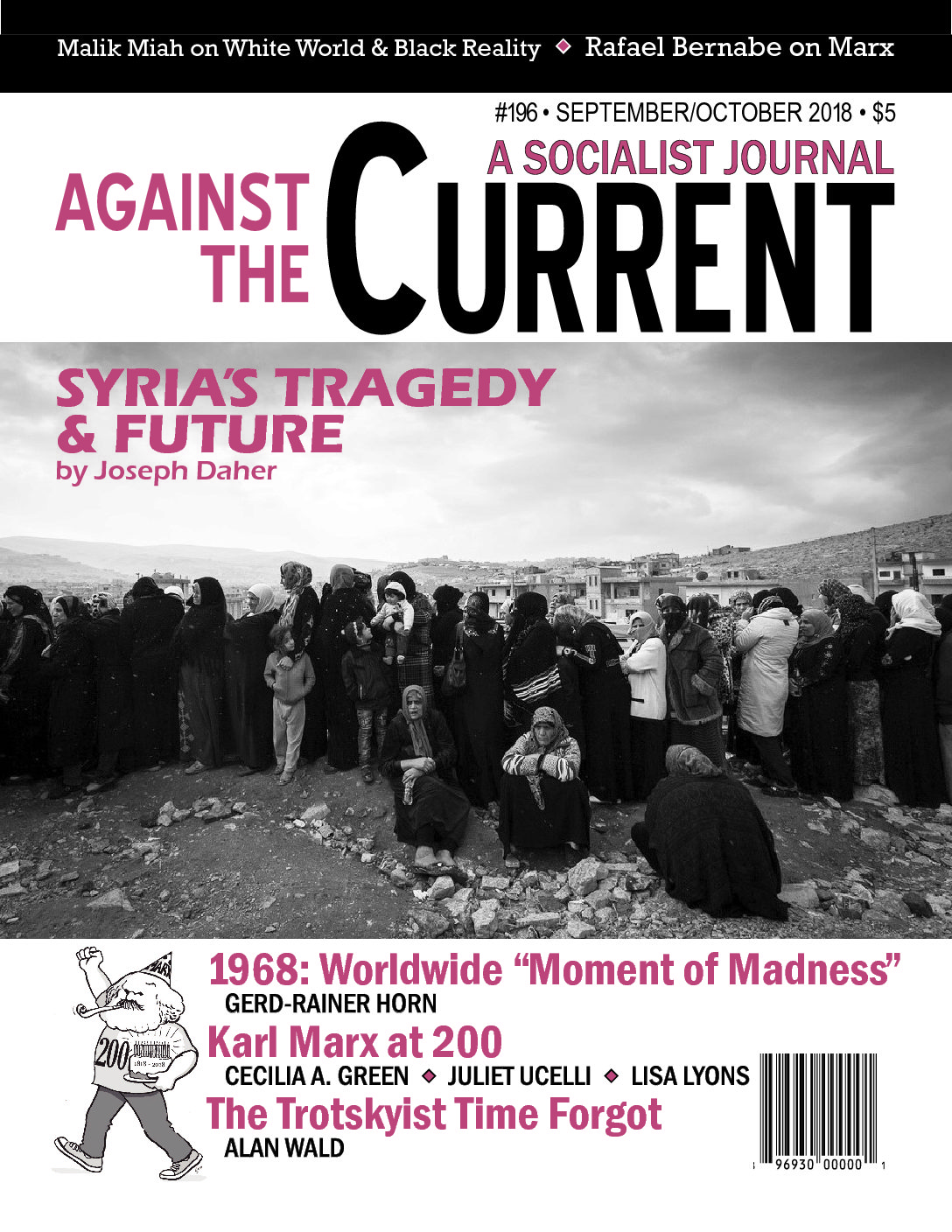

Against the Current, No. 196, September/October 2018

-

Where to Begin?

— The Editors -

The White World and Black Reality

— Malik Miah - Who Killed Marielle?

-

Worldwide "Moment of Madness"

— Gerd-Rainer Horn -

European Communist Parties and '68

— Gerd-Rainer Horn - Fascist Attack in Chile

- UPS Update

- Update on Syria

-

Syria's Disaster, and What's Next

— Joseph Daher - Karl Marx at 200

-

Janus and My Ode to Capital

— Juliet Ucelli -

Historical Subjects Lost and Found

— Cecilia A. Green - Review Essay

-

Marx Turns 200: A Mixed Gift

— Rafael Bernabe - Marx's Capital

-

On the "Transformation Problem"

— Barry Finger -

Reply

— Fred Moseley -

Marx, Engels and the National Question

— Peter Solenberger - Revolutionary History

-

Nicolas Calas: The Trotskyist Time Forgot

— Alan Wald - Reviews

-

Struggling for Justice

— Cheryl Higashida -

The Power of Story, the Evidence of Experience

— Sarah D. Wald -

An Unrepentant '68er's Life

— K. Mann - In Memoriam

-

Martha (Marty) Quinn, 1939-2018

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Joel Kovel (1936-2018)

— DeeDee Halleck and Michael Steven Smith

Gerd-Rainer Horn

IN MORE WAYS than one, 1968 shook up the world of the European Left — perhaps most of all the universe of Communist Parties.

For some time already, some Western European Communist parties had begun to loosen the umbilical cord tying them to the Kremlin, most prominently so the Italian Communist Party (PCI). But for Communist Parties tentatively striking out in the direction of at least some degree of autonomy from Moscow, it was the Prague Spring [the reform movement in Czechoslovakia, which was crushed by the Soviet invasion — ed.] that constituted the crucial event — and only to a lesser degree, the massive social movements occurring all throughout the world to the west of the Iron Curtain.

During the Hungarian (and Polish) revolts of 1956, Western European Communist Parties had still closed ranks behind the repressive phalanx of Soviet-dominated counterrevolutionary actions and words. In the wake of the Prague Spring, the PCI daily l’Unità was frequently removed from newsstands in Eastern Europe due to their editorialists’ outspoken critique of Moscow.

Most other Western European Communist Parties were less overtly critical, but by the early 1970s “Eurocommunism” began to become the talk of the town. The Italian, Spanish, Belgian, British and other Communist Parties now began to form tentative links between each other in an effort to chart a new course.

If few observers in the ranks of the Western Left shed a tear over the long-overdue movement towards a sometimes substantial degree of independence on the part of some Western European Communist Parties, such moves were almost invariably accompanied by a softening of the socially critical edge which had differentiated European Communist Parties from their social democratic counterparts.

Interestingly, those Communist parties who remained solidly pro-Moscow in the wake of the Prague Spring, such as the Portuguese or one of the two Greek Communist Parties, by and large remained more socially radical than their Eurocommunist sister organizations.

In hindsight, it is clear that the Eurocommunist interlude of the 1970s and early 1980s would be the first step in a long sequence of ongoing moderation of Communist Parties’ political edge, which ended in the cases, for instance, of the British and Belgian Communist Parties in outright self-dissolution.

The formerly most powerful Communist Party outside the Soviet sphere of influence, the PCI, saw its slow but steady conversion into a cheap copy of the United States Democratic Party, the Partito Democratico of Matteo Renzi and associated politicians of the abjectly unprincipled kind.

But what about the impact on Communist Parties of the vast social movements tearing up the Western world in and around 1968? It is a clear proof of the long-past-expiration-date of Moscow-oriented parties by the 1960s that none of them played a truly flagship role in the social and political struggles of that era — with the partial exception of the Greek, Spanish and Portuguese Communist Parties then laboring in conditions of illegality, prison and exile.

In the democratic countries of Western Europe, some Communist Parties, such as the French, were openly hostile towards the most vital forms of the burgeoning social movements of that period. The PCI, the Western European party which proved to be the least openly hostile towards the quickly growing New and Far Left, essentially affected an air of benevolent neutrality.

In brief, then, 1968 formed a clear signpost in the evolution of the European Left. Communist Parties were no longer allies of actually existing social movements. An era had come to a definitive end.

September-October 2018, ATC 196