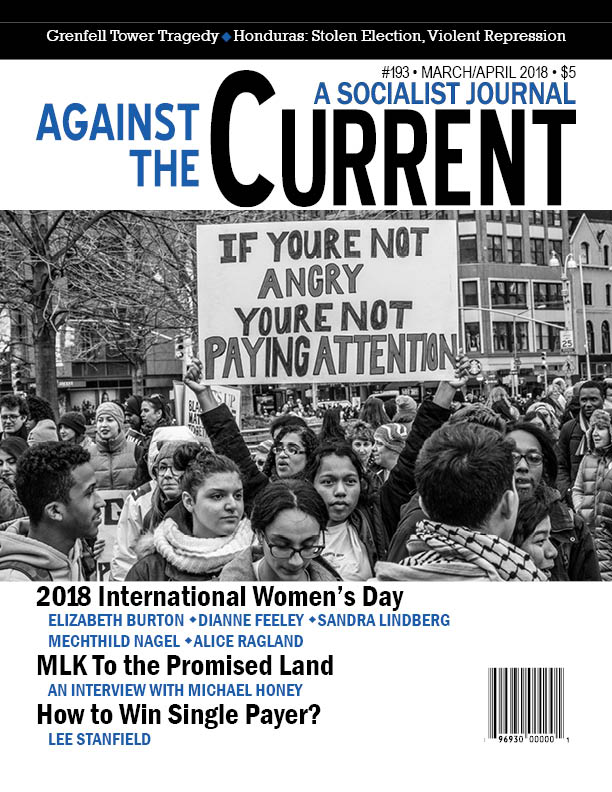

Against the Current, No. 193, March/April 2018

-

#MeToo for All Women

— The Editors -

The New Poor People's Campaign

— Malik Miah - Essential Principles of the Poor People's Campaign

-

A Window on Inhuman Detention

— Yihwa Kim -

Single Payer: What Will It Take to Pass It?

— Lee Stanfield -

The Fight for Housing, 1967-68 & Milwaukee NAACP Commandos

— Mike McCallister -

After the Grenfell Tower Fire

— Sheila Cohen -

Honduras: U.S. Support for Repression & Fraud

— Vicki Cervantes -

Moroccan Catastrophic Convergence

— Jawad Moustakbal -

MLK: To the Promised Land

— Charles Williams interviewing Michael Honey -

Sex and the Russian Revolution

— Peter Drucker -

The 1970s: Finally Got the News!

— Charles Williams interviews Brad Duncan - 2018 International Women's Day

-

Readings: Intersectional Black Activists

— Alice Ragland -

For International Women's Day: Honoring the Fighters

— The Editors -

Reproductive Justice in an Age of Austerity

— Dianne Feeley -

Dialectics of Revolutionary Learning

— Mechthild Nagel -

The Patriarchal Stranglehold

— Elizabeth Burton -

"Embodied Materialism" and Ecosocialism

— Sandra Lindberg - Reviews

-

Worldwide Wobblies Remembered

— Fran Shor -

One Hundred Years, "We" Past and Present

— Sam Friedman - In Memoriam

-

William A. Pelz

— Patrick M. Quinn & Eric Schuster

Alice Ragland

Domestic Worker Organizers, 1960s-1970s

In the mid-to-late 20th century, while the Civil Rights movement was well under way, Black domestic workers spearheaded a movement of their own. Dorothy Bolden, Geraldine Roberts, Josephine Hulett and other African-American household laborers fought for respect, professionalism, and improved working conditions for their profession.

When 1930s New Deal legislation expanded protections for workers, domestic laborers and farmworkers were completely omitted. Since the vast majority of African Americans were employed in these fields at the time, this was an intentional and racist exclusion.

Fed up with their exclusion from workers’ protections, domestic labor organizers formed unions and lobbied for the Fair Labor Standards Act, including the federal minimum wage, to be extended to household workers.

The women of the domestic workers’ movement also wanted to be able to go to work without being sexually assaulted by the white men in the homes they worked for, and without being forced to do degrading, backbreaking labor for inadequate compensation. They wanted to be treated as professionals, not as “mammies.”

In order to meet these goals, the domestic labor activists recruited and organized household workers in public spaces such as bus stops while they waited to be transported to the homes in which they worked.

The household workers’ movement faced exclusion from the mainstream labor movement, which deemed them unorganizable. While the white, male factory worker was the archetypal worker represented by the U.S. labor movement, racism and sexism caused domestic labor to be devalued and delegitimized by the mainstream labor movement and by elected officials.

Because more than 80% of working Black women worked in domestic service up until the mid-20th century, Black women were largely excluded from labor organizing. Because of this, the household workers’ movement had to fight for their rights on their own.

The movement helped to bring respect and professionalism to the domestic workers’ profession. In addition to improving the public perception about domestic workers, their creative organizing tactics have been used as a model for organizing other workers who have been excluded from workers’ protections, including service sector, temp workers, and part-time employees. The household workers’ organizing methods have had a major impact in the current landscape of labor organizing.

Read: Household Workers Unite: The Untold Story of African American Women Who Built a Movement by Premilla Nadasen. Also of interest: Tera Hunter’s To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War.

Callie House and Reparations

Callie House fought to secure reparations for former slaves during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. House believed that African Americans had a right to pensions for centuries of unpaid, involuntary labor. She knew that former slaves, who were left with nothing after emancipation and thus faced extreme poverty, would not have such a difficult time surviving if they received a monthly pension.

As assistant secretary of the Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association, House led the movement for reparations and asserted to the Federal Government that it was the right of former slaves to be granted compensation for their forced labor and the legacy of poverty it left for African Americans.

The U.S. federal government, particularly the Post Office, attempted to suppress the pension movement by denying the Ex-Slave Association the use of the mail — the principal way for the association to communicate with its members and to conduct financial transactions.

The government also sent Pension Bureau inspectors to spy on Ex-Slave association meetings, accused the association of fraud, sent letters asking former slaves to report anyone who told them that the pension bill had been passed, and threatened to fine or jail anyone who attempted to make these claims.

The government continued to make false claims against the association, enact harassment policies against it, and deny it the use of the mails. Callie House retaliated against these attacks by writing replies to the letters she received from the Post Office Department decrying the government for the wrongs that it committed against Black people.

She did not back down from their assaults, and eventually was jailed for having been convicted of fraud in the government’s attempt to end the pension movement once and for all. Though her imprisonment did quell the association’s legislative activities, calls for reparations did not end.

Callie House’s fight for ex-slave pensions caused a ripple effect for future demands for reparations. Following her legacy, other movements and activists have called for compensation for the descendants of slaves.

The Black Nationalist movement of the 1920s, the Nation of Islam, Audley “Queen Mother” Moore, the Republic of New Africa, the African American Reparations League, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Whitney Young, and others have made public calls for various forms of reparations.

The debate about reparations has been reenergized by Ta’Nehisi Coates’s “A Case for Reparations,” which appeared in The Atlantic in June 2014.1 Callie House’s activism spearheaded the calls for reparations that still resonate today.

Read: My Face Is Black Is True: Callie House and the Struggle for Ex-Slave Reparations by Mary Frances Berry

Sojourner Truth: “Ain’t I A Woman?”

Sojourner Truth was a renowned abolitionist whose fight for freedom did not cease after emancipation in 1865. Truth’s intersecting identities as a Black person, former slave and a woman meant that her freedom was denied in many ways after the end of slavery.

After the Civil War, Truth continued to deliver speeches advocating for African-American rights in general and Black women’s rights in particular. Her address at the 1867 American Equal Rights Association Convention highlights her continued struggle for equality and for black women to be considered at all in debates about rights.

The 1867 AERA convention included much deliberation about rights for white women and Black men, but Black women were effectively excluded from the conversation. To point this out, Truth said toward the beginning of her speech, “There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about colored women…”2

She went on to discuss the fact that Black women are paid much less for performing the same jobs as men even though they work just as hard. Truth advocated equal pay for equal work long before modern debates about it brought the issue into the national spotlight.

Sojourner Truth also argued for universal suffrage without property qualifications, knowing that poor people, particularly former slaves, would not qualify to vote if property requirements were upheld. She used her platform as an orator and activist to struggle for Black women’s freedom, which she knew was a necessary precondition for everyone else to be free.

Read: Narrative of Sojourner Truth by Sojourner Truth. Also of interest: Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol by Nell Irvin Painter

Notes

1. Full article available at http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

2. Full text of Truth’s 1867 AERA Convention speech retrieved from http://www.womensspeecharchive.org/women/profile/speech/index.cfm?ProfileID=104&SpeechID=674

March-April 2018, ATC 193