Against the Current, No. 190, September/October 2017

-

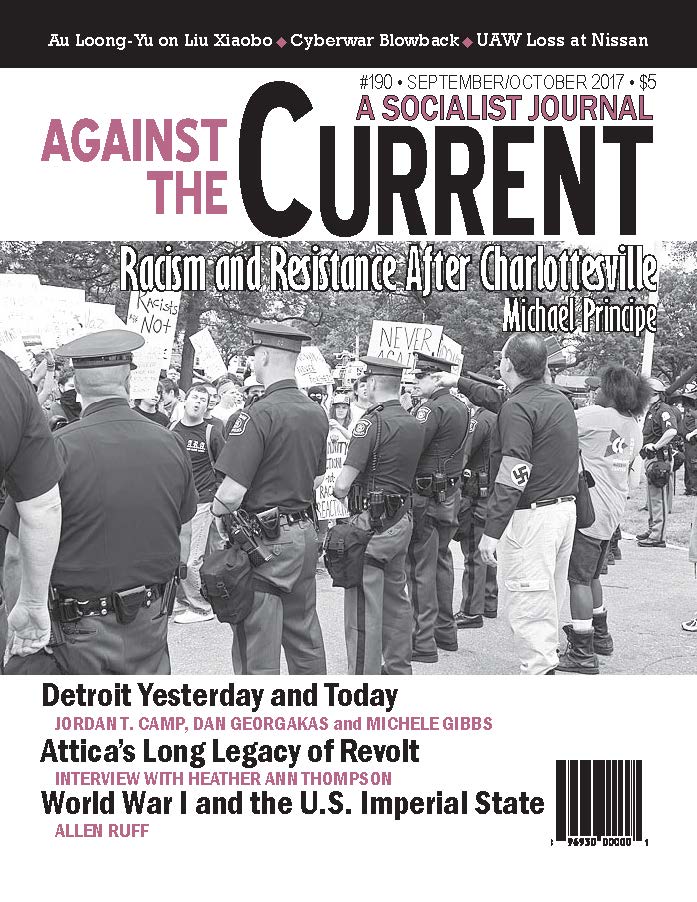

The War Is At Home

— The Editors -

When White Supremacists March

— Michael Principe -

Choices Facing African Americans

— Malik Miah -

How the UAW Lost at Nissan

— Dianne Feeley -

Did Scandal Tip the Balance?

— Dianne Feeley -

NSA's Cyberwarfare Blowback

— Peter Solenberger -

The Murder of Kevin Cooper

— Kevin Cooper -

Attica from 1971 to Today

— interview with Heather Ann Thompson -

The Trial of Sacco and Vanzetti

— Marty Oppenheimer -

Mourn Liu Xiaobo, Free Liu Xia

— Au Loong-Yu -

Under Attack at San Francisco State University

— Saliem Shehadeh -

Dawn of "Total War" and the Surveillance State

— Allen Ruff -

Solidarity Message to Egyptian Website

— The Editors - Fifty Years Ago

-

Detroit's Rebellion & Rise of the Neoliberal State

— Jordan T. Camp -

Chronicle of Black Detroit

— Dan Georgakas -

For Mike Hamlin

— Michele Gibbs -

Mike Hamlin (1935-2017)

— Dianne Feeley - Suggested Readings on/about Detroit's 1967 Rebellion

- Reviews

-

BLM: Challenges and Possibilities

— Paul Prescod -

The People vs. Big Oil

— Dianne Feeley -

Immigration's Troubled History

— Emily Pope-Obeda -

Paradoxes of Infinity

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

Mourn, Then Organize Again

— Michael Löwy -

Making Their Own History

— Ingo Schmidt -

The Wheel Has Come Full Circle

— Mike Gonzalez

Mike Gonzalez

What Went Wrong

The Nicaraguan Revolution: a Marxist analysis

By Dan La Botz

Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2016. (Haymarket paperback edition forthcoming, Fall 2017)

THE MID-1970S WERE a difficult time for socialists. The euphoria of the sixties, and its promise of revolution, came to a sudden and dramatic stop on September 11, 1973.

The military coup that overthrew the government of Salvador Allende in Chile ended the promise of a non-violent “Chilean road to socialism.” The Chilean Communist Party, just days before the coup, had condemned “the violence of left and right,” as if the two were equivalent. Pinochet (Chile’s military dictator) demonstrated how devastatingly wrong they were.

Yet two months later, the powerful Italian Communist Party adopted what it called “the historic compromise” on the basis of what had happened in Chile. In effect it argued that revolution was impossible, and that the best that could be hoped for was a “progressive alliance” with the middle classes.

By the mid-seventies, the military were in power in Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Guatemala and El Salvador as well as Chile. In Central America the military dictators that Roosevelt had described as “sons of bitches, but ours.” held power by terror — and none more than the third of the Somoza dynasty in Nicaragua.

Yet on July 19, 1979, his regime had gone, overthrown by a mass movement led by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN).

Hope and Defeat

The Nicaraguan Revolution restored the hope of revolution.

The mass movement was more advanced at the time in neighboring El Salvador, yet Nicaragua was the first Central American domino to fall.

It seemed to be a new kind of revolution. Its leaders were armed guerrillas, but the new government included liberation theologians as well as poets, and a number of women, and its political discourse was very different from the dry dogmatics of Stalinism.

A year later the Workers Party (PT) in Brazil was formed, and it too fused the language of liberation theology, peasant resistance and Marxism.

The truth is that very little was known about the country or the Sandinistas before the Revolution of 1979. When Somoza was killed a year later he was mourned by no one, and when Ronald Reagan channeled arms to Central America and financed the right wing Contra resistance to the Sandinistas, solidarity became the watchword.

A decade later, in 1990, the Sandinistas were voted out of government, to the shock and disbelief of many international supporters. The contra war had taken a terrible toll, but there were deeper political reasons for the disillusionment of many Nicaraguans with the Sandinistas in power.

As Dan La Botz explains in this thorough and thoughtful analysis, what remains today of the Nicaraguan Revolution is its grotesque parody in the mouths of Daniel Ortega and his attendants, who have created a new dynastic tyranny in its name. But What Went Wrong is far more than nostalgic reflection or retrospective wisdom.

This book, as its full title suggests, is an analysis for Marxists and a tool for understanding. And it appears at a critical moment, as the Venezuelan Revolution descends into chaos and Ortega oversees the planned ravaging of his tiny country by Chinese earth movers clawing out a transoceanic canal whose only beneficiaries would be the new capitalist class, “on a Latin American scale,” whose rise La Botz analyzes here.

This new formation is a fusion of ex-revolutionaries and the old bourgeoisie, whose radical discourse is simply a mask for an enthusiastic neoliberalism. And the phenomenon is not limited to Nicaragua.

Yet the way in which it emerged and held power there is an object lesson for other processes.

The FSLN Revisited

After 1979 there was a flurry of writing on Nicaragua and a rush to find out more about this obscure organization, the Sandinista National Liberation Front.

They were guerrilla fighters in the Guevarist mould, whose first appearance in the international press came with the seizure of the National Congress in 1977 and the subsequent release of imprisoned leaders, including Daniel Ortega.

Their victory in 1979 came as an antidote to Chile, and suggested the opening of a new “road to socialism,” after the Chilean strategy had been drowned in blood.

Yet it was clear at a very early stage that the Sandinistas were not all that they appeared to be. The discourse they shared with the theology of liberation, and with elements of the emerging movement in Brazil, sat uneasily with their political practice.

In his analysis, La Botz explores the political origins and the ideology of the Sandinistas in exhaustive detail. He is emphatic and uncompromising in his conclusions.

The Frente was formed by a group of young communists that included Tomas Borge and Silvio Mayorga, and was dominated by Carlos Fonseca, who was killed in 1976 — ironically while he was attempting to reconcile three warring internal factions.

Fonseca was the unquestioned ideologue of the Frente, and his position shaped the organization from its beginnings. A member of the Nicaraguan communist party (PSN), he was sent to Moscow and remained an uncompromising defender of Soviet Communism.

After 1959 he abandoned the politics of the popular front advocated by the PSN (which translated into collaboration with Somoza throughout its history before 1979) and became committed to the guerrilla strategy and the Cuban model. But as La Botz emphasizes a number of times:

While Fonseca would later change his view of the Communists’ popular front pacifism, he never wrote or said anything to indicate a break with the elements of Stalinist theory or politics, such as the one-party state. (117)

And neither did the Frente or Fonseca’s successors in its leadership. The Marxism-Leninism to which the FSLN leadership adhered was Stalinist in other ways too.

As La Botz discusses, a guerrilla strategy saw the armed cells (or focos) as the protagonists of revolutionary struggle. The concept of the self-emancipation of the working class, to which La Botz and most revolutionary Trotskyist currents adhere, had no place in the FSLN’s strategy.

To that extent the Cuban model, which shaped both the resistance strategy and the perspectives of Sandinismo in power, was compatible with Fonseca’s Stalinism and, as we shall see, with collusion with the capitalist class under Ortega’s corrupt dominion.

This is a critical contribution of La Botz’s work to the discussion of socialist politics in Latin America. And it is wholly consistent with the origins of the Sandinista tradition.

La Botz explores the politics of César Augusto Sandino, who sustained armed resistance to the domination of the United States and the regime of the first Somoza, until he was murdered in 1934. Sandino’s politics of armed struggle were not socialist; he dismissed Farabundo Martí, his secretary for a while, who was a Marxist and the organizer of the attempted rising of 1934 in El Salvador.

Dan paints a comprehensive portrait of this charismatic and resolute leader who was driven by a curious mixture of liberalism and spiritualism, but who held unquestioned authority within what his biographer Gregorio Selser described as his “crazy little army.”

Sandino’s legacy provided the FSLN…with a model of revolutionary leadership and struggle, but it did not provide a vision of socialism nor did it offer a model of democracy. (73)

And neither did Stalinist Russia nor Cuba, of course. Instead the military structures and relationships characteristic of a guerrilla army were transferred directly to the structures of a new state.

“We Await Instructions”

For revolutionary socialists in the tradition that Dan La Botz and I share, the subjects of revolution are the working classes, and revolution is the moment when they become the governors of their own lives.

This is a very different concept from a transformation directed and controlled from above in which the mass organizations, the trade unions and the grass roots expressions are simply conduits carrying out instructions.

Like many of us, La Botz was surprised by the dominant slogan shouted at Sandinista rallies — “Dirección Nacional Ordene” — “National Leadership We await instructions.” Despite its claims, this called into question the nature of the people’s revolution.

When I was in Nicaragua in 1982, sitting on a bus between Managua and Masaya, a long black Mercedes with smoked windows slid by. “There goes a comandante,” the passengers shouted in unison. And in fact the FSLN leadership had taken over houses and estates, as well as cars, belonging to Anastasio Somoza and his associates for their own use.

It was unmistakably revealing of the political relationship envisaged in the Frente’s politics between the leaders and the mass base. What Went Wrong explores in considerable detail how that relationship developed at every level of power, and how it led directly to errors whose consequences would be tragically destructive.

The hostile relationship of an essentially white middle-class leadership with the black and indigenous population of the Atlantic coast, the product of ignorance and arrogance, alienated both communities to the extent that significant numbers of them joined the counterrevolution, the contras.

The long delay in providing deeds to small farmers stemmed from a dogmatic suspicion of the peasantry, and alienated a significant part of the rural population.

The Sandinistas, nevertheless, enjoyed an unprecedented level of external support – from solidarity movements and the Socialist International among others.

In the final year before the overthrow of Somoza, the resistance to the dictatorship was represented by Los Doce, a group of leading figures from Nicaragua’s business class, intellectuals, and religious representatives. The Sandinistas among them did not declare their affiliation, and allowed the impression that this movement was essentially social democratic in its outlook.

According to LaBotz, this was a deliberate policy, concealing what was an unchanging hard-line Marxist-Leninist (that is, Stalinist) position behind a more flexible and ambiguous public appearance.

The successful early literacy and health campaigns, which attracted a great deal of foreign support, confirmed the impression. The mass organizations created after 1979 reinforced it; yet all of them were created from above by a national leadership that gave no account of itself to them, nor created any organs of participatory democracy that could correspond to the rhetoric.

It is true that the highly centralized character of the FSLN and the domination of its central cadre at all levels was visible at an early stage. But it is also the case that its external supporters did not see it, or chose not to. The Sandinistas were viewed with a high degree of romanticism, uncritically, as idealized third world revolutionaries.

The response from Washington confirmed the impression. The Reagan administration’s bitter hostility to the Sandinistas had become very obvious during a presidential campaign in which Nicaragua (population just over three million) was represented as posing an imminent threat to the United States.

The memory of Vietnam was still very raw on the one hand, and on the other the exaggerated threat posed by the Nicaraguan revolution provided a focus for a renewed flexing of imperialist muscle.

Economic pressures were quickly followed by the financing and arming of the contra force, which led to the murder and maiming of tens of thousands of Nicaraguans.

After 1990

The February 1990 election, which the Sandinistas lost to a heavily financed right-wing coalition led by Violeta Chamorro, was greeted with profound shock by their supporters — as La Botz remembers in the United States and as I can testify in Britain.

Yet the introduction of military conscription by the then president Daniel Ortega, without consultation, had provoked a dramatic reaction among Nicaraguans, and the Contra war was claiming its rising human cost at the same time.

It was only after the electoral defeat that the Sandinistas called their first ever membership convention, albeit under strict control by the leadership. There was still neither a new Constitution in place nor an economic strategy beyond the 1981 One-Year Plan.

For all the expectations of the peace and solidarity movements, the FSLN leadership remained remote and inaccessible; there were no mechanisms for control from below or even dialogue. And the comfortable life lived by the comandantes was obvious to all.

The aftermath of the election exposed the contradictions. La piñata, as it was called, involved the individual appropriation (or theft to call it by its name) of state property by the Sandinista leadership, all of whom became millionaires as they left office. Again La Botz provides abundant detail.

There were immediate labor strikes in May and June 1990, and again three months later. In the end, the new head of the army under Chamorro, Humberto Ortega, a member of the FSLN National Directorate, imposed an ending by force, partnering the FSLN machine with the new regime.

The demobilized contras who were given land grants, and the demobilized Sandinista soldiers who had nothing, continued their war in the confrontations between recompas and recontras, which became in effect criminal gangs.

The first ever FSLN Convention, in 1991, might have provided an opportunity for retribution or at the very least explanation. But it was a stage on which the battle for post-revolution power was fought out between internal groups.

The character of the post-1990 state was prefigured in the economic decisions taken by the Sandinistas from 1988 onwards and the safeguards provided to private capital (both domestic and foreign).

Having taken everything that was not nailed to the floor, Daniel Ortega on behalf of the Sandinistas now negotiated a power-sharing agreement with Chamorro, in which both agreed to hold off their radical wings and defend common ground. It was a common ground that meant a harsh neoliberal strategy, a rushed return of private property, an increasing authoritarianism and a rising level of corruption — a kind of ongoing piñata.

The only independent organization that existed both before and after the elections was the women’s movement. Daniel Ortega devoted much of his commitment and energy to destroying it, using the support of the Church and the right wing to strike at the very heart of the feminist movement by criminalizing abortion.

It is extraordinary to think that a Congress dominated by the Sandinistas passed the most draconian anti-abortion law in Latin America by 52 votes to 0!

Deafening Silence Descends

The strangest thing was the deafening silence that descended on the solidarity movements after 1990. The question of why a revolutionary movement could produce corruption on such a scale was perhaps too difficult to face. It is to Dan La Botz’s great credit that he does take on the question.

He insists throughout his book that the Sandinistas worked a double strategy, maintaining a secret Stalinist core politics whose object was a recreation of the Cuban state model. At the same time the public face suggested a social democratic program, though without even liberal democratic institutions.

In the end, what emerged was a liberal state overseeing a capitalist system under the control of ex-revolutionaries. The price was paid by a Nicaraguan people collapsing into greater poverty and then faced with a future possibility of providing cheap labor for local and foreign multinationals.

The final section of La Botz’s book is heartbreaking. The National Directorate of the FSLN and its closest associates in alliance with the old bourgeoisie created a new ruling class, running the state and the economy in pursuit of profit. The governments that followed Chamorro were notoriously and openly corrupt; but Daniel Ortega and the Sandinistas were their partners and collaborators at every level.

When Daniel Ortega finally fulfilled his presidential ambition, in 2006, having established dominance and control in most other political and economic institutions, he devoted himself to ensuring his continuity in power by changing the Constitution, removing his internal opponents from their Congressional seats, and persecuting them by every means at his disposal.

The absurd sight of his huge portrait on every street corner, and the creation of the joint presidency with his wife Rosario Murillo, who has created a semi-Messianic vision of Daniel, is a grotesque caricature of the Sandinista promise.

In La Botz’s words, the Sandinistas never were a government of the workers, but created a government over them.

There is some debate over the nature of a government now led by Daniel Ortega and his wife in his fourth presidential term. It is as centralized and authoritarian as Somoza’s — but not based on violent repression.

Its democracy is a sham and the interests it defends are those of the new ruling class, where the ex-Somocista billionaires happily coexist with the ex-Sandinista millionaires. The question that remains is why this happened.

There will be the usual cynical response from those who argue from a notion of a grasping, corrupt human nature. Nicaragua during the years of resistance to the imperialist assault is the best reply to that. Thousands died defending the promise of a different kind of society and thousands more denounced imperialism’s attempts to bring it down.

Others focus their explanations on the devious and manipulative Daniel Ortega. And to the extent that, at least rhetorically, the Sandinista Revolution pointed ahead to the anti-capitalist movement of the century’s end, it is important to look for the keys to its failure.

Considering the Alternative

In his preface, Dan La Botz describes the Central American revolutions of the eighties as a “perfect anti-capitalist storm.” I think it is important to explore what that means.

The movement that grew up in the late 1990s across the world, and which erupted in Latin America, especially with Bolivia’s Cochabamba Water Wars, was deeply and explicitly critical of global capitalism. But as the first expression of post-Stalinist resistance, it was also critical of a socialism that had legitimated tyranny, as became clear after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The suspicion of socialist ideas was reinforced by new currents of thought around Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri and John Holloway, which made a virtue of the absence of a project for political power.

The values of the new movement were anti-capitalist and centered on the idea of participatory democracy and control from below — ideas which were articulated by Hugo Chavez in his call for a “21st century socialism.”

Throughout this study La Botz sets the model of a centralized, authoritarian state against a genuine socialist democracy; he is writing for the first post-Stalinist generation for whom power rests at the base of society and not in its leaders, whatever their discourse.

Yet the reality is that when the Sandinistas came to power in 1979 very few people framed the question in that way. The political project at the heart of Sandinismo was both secret, as La Botz emphasizes, and authoritarian.

The socialist tradition is, above all things, a project for the “self-emancipation of the working class.” The subjects of this process are the working people, and the socialism it foresees is a power controlled and governed from below. But the model that Cuba represents, and which the Sandinistas adopted whole, has no place for genuine workers’ democracy or workers’ control of the economy and society.

Without that, and without the transparency and accountability of the leadership that that implies, Daniel Ortega was able to appropriate the Nicaraguan state for his own purposes.

It is not simply a matter of individual betrayal or personal corruption — though both are very real. Ortega continues to represent himself as a Bolivarian, which has ensured millions of dollars of support from Venezuela. The explanation goes further than individuals.

Corruption, the blind pursuit of power, and the betrayal of the socialist promise will always be possible behind closed doors. Without accountability, without genuine democratic control from below, the Nicaraguan experience can repeat itself.

But there is nothing inevitable about that. The first decade of the 21st century in Latin America showed that real movements from below can remove dictators and take control of their society. It showed that there is a logic of revolutionary movements that stand for a pluralist, anti-capitalist democracy and can fight for it.

But there is also another logic, the logic of a battle for leadership that can and does lead away, towards the kind of outcome of which contemporary Nicaragua is one more powerful example. It restates the most fundamental of principles — that socialism means, above all, an authentic, socialist democracy, or it means nothing.

September-October 2017, ATC 190