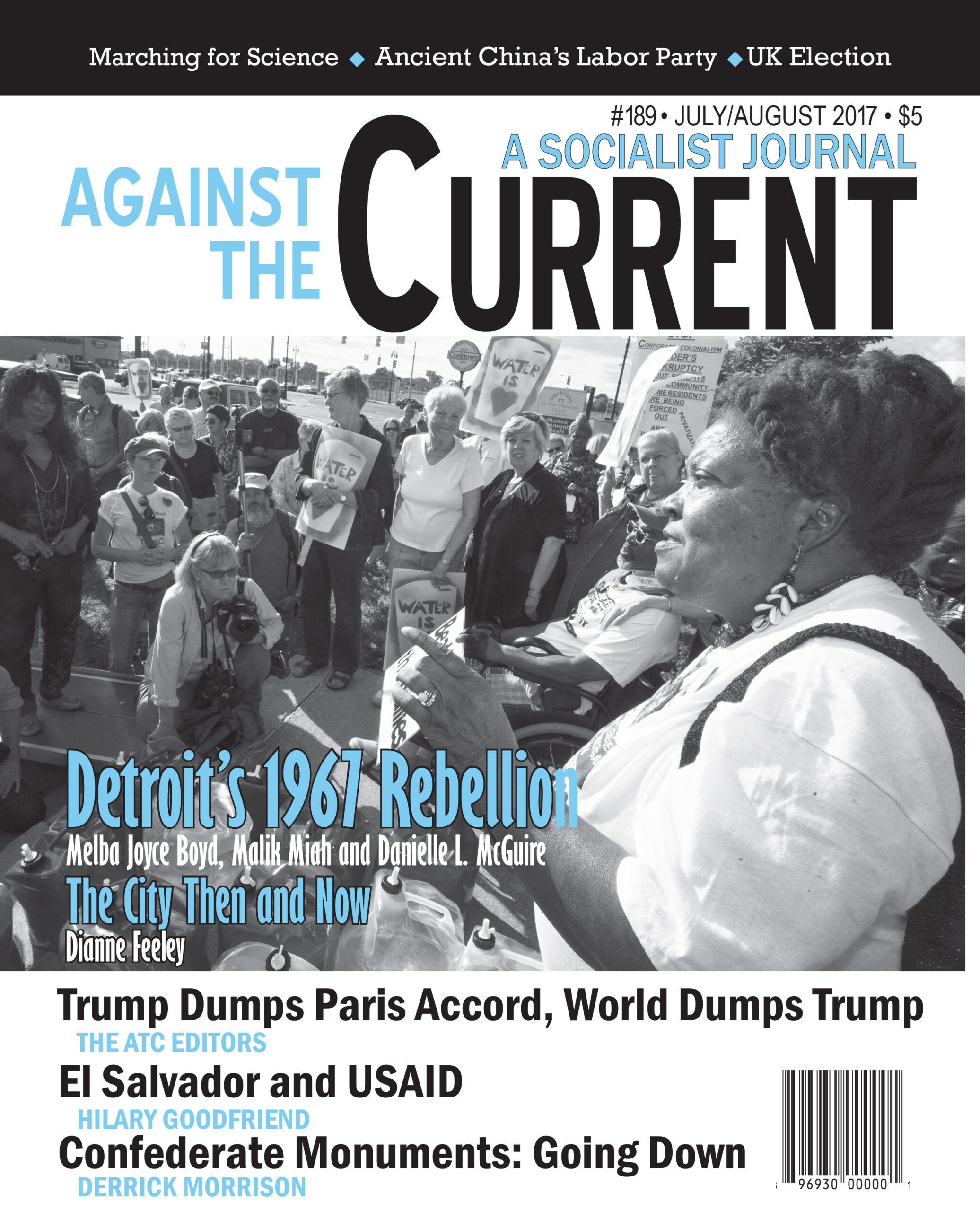

Against the Current, No. 189, July/August 2017

-

The Longest Occupation

— The Editors -

One-Half Cheer for Trump?

— The Editors -

Marching for Science and Humanity

— Ansar Fayyazuddin -

California Science Marches

— Claudette Begin -

Confederate Monuments Down

— Derrick Morrison -

Theresa May's Katrina

— Sheila Cohen and Kim Moody -

USAID in El Salvador: The Politics of Prevention

— Hilary Goodfriend -

China's Ancient Labor Party

— Au Loong-yu - Sweatshop Shoes for Ivanka

- Fifty Years Ago

-

Detroit's Rebellion at Fifty

— Malik Miah -

Roots of the Rebellion

— Kim D. Hunter interviews Melba Joyce Boyd -

Murder at the Algiers Motel

— Danielle L. McGuire -

A Tale of Two Detroits

— Dianne Feeley - Reviews

-

Birth of the "Open Shop"

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Teachers as Change Agents

— Marian Swerdlow -

The World and Its Particulars

— Luke Pretz -

The Unraveling Middle East

— Kit Adam Wainer -

The World Through African Eyes

— Anne Namatsi Lutomia -

Poland's Solidarity and Its Fate

— Tom Junes -

The Russian Revolution: Workers in Power

— Peter Solenberger

Anne Namatsi Lutomia

Securing the Base:

Making Africa Visible in the Globe

By Ngugi wa Thiong’o

Seagull Books, 2015, distributed by University of Chicago Press, 130 pages, $25 cloth.

THE ESSAYS IN Securing the Base are united by a concern for the place of Africa in the world today. The iconic Kenyan writer and former political prisoner Ngugi wa Thiong’o maintains that any discussion of the continent must take into account the depths from which Africa has emerged.

From the struggle against the odds posed by the slave trade, colonialism and debt slavery, the author maintains positives have emerged. (ix) In the preface he clearly outlines his objective: “Underlying all the essays is a call for a visionary, united African leadership to secure the continent and its resources and take responsibility of its future.” (xv)

Edward Wilmot Blyden, H. Silverster Williams, Amy Ashwood Garvey, W.E.B. Du Bois, C.L.R. James, Kwame Nkrumah, George Padmore and Frantz Fanon, along with a whole range of others, imagined a united Africa that would be the base for all peoples of African descent. They envisioned an Africa without internal borders, playing its legitimate role in the community of nations. But can an Africa of many languages and cultural tendencies unite? (48, 52)

Unity Is Key

Professor Ngugi wa Thiong’o teaches English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Irvine. He is probably best known for his novel A Grain of Wheat. Writing both novels and non-fiction, he is also the author of The River Between, Petals of Blood, Wizard of the Crow, and Decolonizing the Mind. In recent years he has turned his writing and activism to the recuperation of African languages.

In Securing the Base: Making Africa Visible in the Globe, Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s essays span three decades. The earliest was written in 1982, the latest in 2009. Within seven chapters Ngugi traces the effects of slavery, colonialism and neocolonialism, discusses nuclear disarmament, and speaks out against unbalanced power in a global system that privileges the few at the expense of the majority.

He argues for the formalizing and valuing of indigenous African languages and points to the hopeful possibility of a united Africa that can take its economic and political position in the world. He points out that the forces of global reaction will try to divide and dominate Africa so unless it meets this challenge in a rapidly globalizing world it will remain “invisible.” (58)

Ngugi’s optimism is based on the human and natural resources that the continent contains as well as its vast space. In his vision:

“Even within capitalist assumptions, the way to go is to develop an intra-African communications-village to village, town to town, region to region, east, west, north and south. The challenge is to make African diversity in languages, culture and religions a strength, not a weakness. It is only a united Africa and vision of tomorrow that can bring about visibility. The new Africa must be reflected in Africa’s place in the world.” (xvi)

Holding the Middle Class Accountable

According to Tatah Mentan(1), the crisis in Africa is due to collapsed economies, the international marginalization of the continent in trade and global affairs and political instability. Consequently a majority of Africans live in abject poverty that could be alleviated if progressive policies were enacted. Ngugi writes that “The economic and political praxis of the ruling middle class that systematically excludes the majority are rooted in the culture it has critically absorbed.” (41)

Relatedly, Ngugi argues that discussions about the colonial history of Africa have to be held in tandem with Africa’s failure to hold itself responsible for its crimes. Ngugi calls for the middle class(2) — which he sees as a class mimicking western values — to be held responsible for participation in the slave trade, colonialism and the current economic disparities.

With the aid of the European bourgeoisie, what Ngugi observes as a Corporate Tribe of the West has emerged, working together with the West to oppress and suppress Africans. He reminds us of Fanon’s assertion that the African middle class learned from the European bourgeoisie not to value the lives of the poor at a personal and geopolitical level.

While Ngugi holds the African middle class responsible for continuously betraying the unprivileged in Africa, he also acknowledges the roles of the intellectual as forerunners of freedom fighters in various African countries. He hails their work in raising consciousness among Black people on different continents.

Intellectuals can and must explore possibilities and logical implications of their chosen fields and form. But I hope that the intellectuals of our times believe in the contact of cultures as oxygen of the human community; that in the struggle for peace and nuclear disarmament, for social justice and for cultural exchange, today’s intellectuals can find what they need further facilitate the generation of more oxygen, thus enabling a shared human inheritance of the best in all faiths, doctrines, culture and languages. (112)

In the second chapter, “Privatize or Be Damned: Africa, Globalization and Capitalist Fundamentalism,” Ngugi examines how the global bourgeoisie participates in making Africa invisible. Ngugi traces the West’s exploitation of world markets by showing the interconnections of the industrialization period, colonialism, the Cold War, the establishment of the Bretton Wood institutions, the growth of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Africa and the rise of Chinese foreign direct investment in Africa.

Ngugi criticizes institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank for assuming the right to formulate national policies, thus weakening nation-states. A case in point would be the Structural Adjustment Program (SAPs) of the late 1990s.(3)

Making African Languages Count

According to Ngugi, language is at the core of the class divide within African nations. He aptly borrows from the economic notion of the trickledown effect to discuss how knowledge only trickles down in Africa because intellectuals do not produce knowledge but use the language and framework of colonialism.

It is not hard to see the roots of this identification with cultural symbols of Western power. The education of the black elite is entirely in European languages. Their conceptualization of the world is within the parameters of the language of their inheritance. Most importantly, it makes the elite an integral part of a global-speech community. Within the African nations, European tongues continue to be what they were during the colonial period: the language of power, conception and articulation of the worlds of science, technology, politics, law, commerce administration and even culture. (42)

Ngugi calls for the unification of Africa at two levels, physically as a continent and intellectually by foregrounding its African languages. “Any further linguistic additions should be for strengthening, deepening and widening this power of the languages spoken by the people.” (50)

Memory and culture are expressed through language; they also are the medium through which reality is constructed. In valuing indigenous languages, the majority can begin to engage in intellectual production through the means at their disposal. They then join the ranks of innovators and knowledge producers instead of being dull consumers.

Elsewhere, Ngugi has stated that all languages should be treated equally — even the colonialist language should not be completely eradicated. He acknowledges that some see the multiplicity of African languages as a negative aspect and question the capacity of African languages to support sophisticated social concepts — or scientific thought itself.

A Question of Hope

Ngugi makes the case that Africa is still presented as backward when compared to the West. He demonstrates this by problematizing how Africans are identified. Africans are seen as tribal: 300,000 Icelanders are spoken of as a nation, while 30 million Nigerian Igbos are regarded as a tribe.

Ngugi sees this identification as problematic for Africans because its blocks the possibility of unity or empathy for those who look like them. He sees this as being at the core of ethnic genocide in Rwanda, Darfur and Kenya during post-election violence. Thus he wants to “strengthen the base,” which means unifying Africa. And he sees unity of the African continent as emerging out of a voluntary people-led base.

From one point of view, Securing the Base is not only a collection of essays but a workbook that speaks of global contradictions and nudges Africans and other citizens of the world to make the necessary change — dismantling globalization and capitalist fundamentalism through changing the marketing system, including nuclear weaponry.(4)

For Ngugi historical inequalities are related to binary relationships between the dominant and subjugated, the West and Africa, the Have and Have Nots. He regards the belief in “the market” as capitalist fundamentalism, which mirrors the characteristics found in religious fundamentalism.

Ngugi disrupts the status quo by providing thought-provoking historical points in the world and his native country Kenya to clarify his argument. He dares to dream of a world that is otherwise deemed to be impossible — a united Africa at par with the other nations. Having indicted several groups for being responsible for where Africa rests now, Ngugi leaves us with the message of hope for a united Africa.

Notes

- Mentan, T. (2004) Dilemmas of weak states: Africa and transnational terrorism in the twenty-first century, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

back to text - Africa now has the fastest-growing middle class in the world. According to The Pew Research Centre, an American consulting firm, only 6% of Africans qualify as middle class, which it defines as those earning $10-20 a day.

back to text - Typical stabilization policies included: deficit reduction through currency devaluation, budget reduction or austerity, restructuring foreign debts, monetary policies, eliminating food subsidies, raising the price of public services, cutting wages and decreasing domestic credit.

back to text - This book can be cross read with other African writers’ books such as Adichie, C. N. (2006), Half of a yellow sun. Alfred a Knopf Incorporated, Bloom, H. (2009). Chinua, A. (1958). Things fall apart. Ayittey, G. B. (1999). Africa in chaos. Palgrave Macmillan, Mbembé, J. A. (2001). On the postcolony (Vol. 41). University of California Press.

back to text

July-August 2017, ATC 189