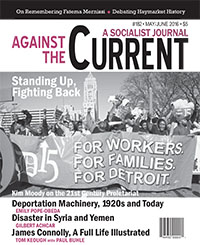

Against the Current, No. 182, May/June 2016

-

Politics of the New Abnormal

— The Editors -

Why Blacks Vote for "Pragmatism"

— Malik Miah -

"This Deportation Business": 1920s and the Present

— Emily Pope-Obeda -

Trouble Down in Texas (and elsewhere)

— Dianne Feeley -

Disasters in Syria and Yemen

— an interview with Gilbert Achcar -

Russia's Intervention and Syria's Future

— Gilbert Achcar -

Fatema Mernissi: A Pioneering Arab Muslim Feminist

— Zakia Salime -

Destroying Detroit Schools

— Dianne Feeley and David Finkel -

U.S. Labor -- What's New, What's Not?

— Kim Moody -

Auto's Permanent Temporaries

— Dianne Feeley - The Murder of Berta Cáceres

-

Free Oscar Lopez Rivera Now!

— Steve Bloom -

Homonationalism and Queer Resistance

— Peter Drucker - An Introduction to the Life of James Connolly

-

James Connolly and the Easter Uprising

— Paul Buhle -

American Literature and the First World War

— Tim Dayton - Review Essay on Haymarket

-

The Contested Haymarket Affair: 130 Years Later

— Allen Ruff -

Messer-Kruse's Haymarket History

— Rebecca Hill - Reviews

-

Water in a World in Crisis

— Jan Cox -

Standing Against Counterrevolution

— David Finkel -

Inside/Outside the Campus Box

— Michael E. Brown

Michael E. Brown

The Cutting Edge

By David Lansky (George Snedeker)

Xlibris LLC, 2014 (200 pages). This book can be ordered by phone at 1-888-795-4274; or by email at Orders@www.Xlibris.com

THIS SATIRICAL NOVEL brings to mind our present reality: It may be that what is happening to universities around the country is so bold in its neoliberal modeling of the corporate enterprise, and its neoconservative tendency to condemn anything remotely connected to critical thinking, that it can only be made comprehensible in a work of fiction.

This has partly to do with the cultural marginalization of education itself in favor of the STEM (Science/Technology/Engineering/Math) curriculum and consequent administrative demands that all disciplines establish quantitative, computable standards for judging academic performance. Dissenting voices are less likely to be heard, and critical scholars are increasingly forced to attempt to recover a sense of the importance of critical work within the same organizational forms that reject it — perhaps in the hope of being able at least to argue against the contexts and powers that sustain those forms.

The Cutting Edge is a compelling and original work that brings these and other aspects of academic life together as a subtext to the life and times of its main characters. Its originality lies in the ways in which what academics do reveals the uncertainty of their desires and the limitations they accept and eventually take for granted. It also lies in the form of this novel, largely composed of a series of revelatory but hopeful “essays” by a student at Old Windsor, Jenny Delight, that comment on campus life with special regard to the admirable wisdom of “our sociology professor.”

One of the many pleasures of this book lies in the humor that emerges from the mix of innocence and guile in Jenny’s writing — with consequent alternations of confusion and idealism — and the inconsistency of college life with whatever might be anticipated after graduation. On the one hand, Jenny knows that life is not like college, yet she hopes for a future that allows her to enjoy the fruits of having learned that the good life requires living “outside the box.”

Jenny finds in her sociology professor an ideal model, despite the institutional limits to every ideal she stumbles on during her participation in the student life committee.

Her first essay, entitled “Why I Love Old Windsor,” begins with a passionate reference to Professor Fred Snyder: “Let me get down to the point. I love my Sociology Professor because he is so cool that he chills me down to the bone. Every time I go to his class, I get moved to inspiration by something he says. He’s what you call ‘outside the box.’ And I’m the kind of student who hates the boxes folks keep their minds locked up in.” (23)

Nevertheless, a certain irony runs through Jenny’s essays. Consider the way in which she resolves her ambivalence about attending college: “Well, it’s back to my studying. It’s midterm time and I have to keep my GPA up so I can get into law school and get rich and keep my ass out of prison. I’ve also got to go to the Broadway Mall to buy some more Makedown to keep the boys hot for me. Well, as I always tell anyone who’ll ever listen: ‘you have to keep keeping on. It’s a hard road we students have to travel.’” (24)

Ambiguities and Moral Hazards

For Jenny, even the most serious of events at Old Windsor must be approached to some extent ironically, as if she is constantly reflecting on the ambiguity of her student existence even as she presents those events as if they had a life of their own. The book also incorporates this attitude in Professor Snyder’s autobiographical essay and in remarks by other teachers and administrators.

For faculty, academic life is portrayed in part as a pretense that most professors can tolerate only in a persistent attitude of self-conscious irony and occasional self-denigration. For the reader, there is another source of irony. The novel never settles the identities of the main characters, which raises the difficult question of whether it is possible to imagine academic life being known from within.

Snyder, who is eventually murdered by an insane student, is a semi-tragic protagonist who represents the possibility of being authentic in the midst of so many temptations toward inauthenticity. The fact that David Lansky is a pseudonym for the book’s author, himself a prominent critical theorist, raises the question of exactly who or what “Snyder’s” own narrative voice represents.

The identity of Jenny herself ultimately comes into question, so that the reader finds herself forced to recognize the academy as a whole, its aspirations and self-defeating compromises, in what otherwise might appear to be idiosyncratic accounts of anecdotes and comments on the life and times of specific individuals.

The most individually self-reflexive voices of various officials, who condescendingly praise Snyder at his memorial service, reflect the ambiguity and moral hazard of hypocrisy that, we are bound to surmise, characterize administration as an occupational condition. The President, Provost and Dean clearly despised him, either for his accusations of official malfeasance or his resistance to certain policies, yet reverted to a self-satisfying display of piety and civility at the service

President Prime allowed that Snyder was entitled to “voice his opinions” when he accused the president of being “more of a real estate speculator than a college president.”

Even the department chair, who apparently liked Snyder, could not disguise a degree of cowardice. He concludes his own comments with a mention of the reactionary chief of police, who “would have turned Old Windsor into a police state if people like Fred Snyder had not stood up to him. This was no easy job. I’m very happy that it was Fred who took on Danniello and not me.” (200)

It is no wonder then that Jenny, the student as an altogether believable type, is willing to respect thinking and acting “outside of the box” while apparently remaining indifferent to the consequences of doing so.

Her account of Snyder’s murder is understandably dispassionate: She concludes her terse, almost journalistic description of the murder and the police response by “This is how it all ended: the life of the Professor, the Student Life Committee and my college experience at Old Windsor. It was all over. Everything was now over as far as I was concerned.”

From one point of view, The Cutting Edge is more than a novel. It is also about “higher education,” about the complex and often contradictory roles it encourages and the ways in which it suppresses its own ostensible values of openness, creativity, experimentation, critically rational thought, and the appreciation of difference.

This is why readers may find Jenny, the Professor, and the university administrators, so familiar and no less problematic for their familiarity. From another point of view, it provides many pleasures, not the least of which is the voice of Jenny Delight — a Salinger-like mix of innocence, realism, and wile that pervades The Cutting Edge as an account of academic life and as a source of the humor that is never absent from it.

This is a wonderful book, which engages the reader by the humor that animates the writing and its achievements of narrative plausibility, and a sense of realization without an overarching plot. In these latter aspects, we see an original piece of writing and an unusual and altogether compelling form of the novel.

It does not attempt to settle anything except by showing unmistakably how unsettled academic life is, but each passage provides something of a provocation. One feels that there will be a punch line, a point of rest, only to find that nothing is completed and that all of these contradictory existences are destined either to remain contradictory or to take refuge in the self-satisfaction provided by their offices or the delusions provided by their dreams.

Yet the novel leaves us with at least some degree of hope. Snyder’s courage and determination suggests what thinking “outside of the box” is like, and the fact that Jenny is not altogether fooled by pretense, are some of what we are brought to recognize in a context that, without this novel, we might be willing to discount or ignore.

May/June 2016, ATC 182