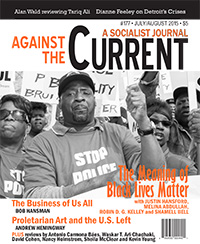

Against the Current, No. 177, July/August 2015

-

Paradoxes of Politics

— The Editors -

Police Violence in the Spotlight

— Malik Miah -

A Majority Black Police Force -- It's Not Enough

— Dianne Feeley -

New Fight to Save Mumia Abu-Jamal

— Brad Duncan -

The Silencing Act and Mumia Abu-Jamal

— Daniel Denvir -

Mass Incarceration for Profit

— Brian Dolinar and James Kilgore -

A Recipe for Killing a School System

— Dianne Feeley -

Detroit's Foreclosure Disaster

— Dianne Feeley -

Albert Woodfox, Gary Tyler

— David Finkel - Black Lives Matter

- Introduction to Black Lives Matter

-

From Ferguson to Baltimore

— Justin Hansford -

The Movement Has a History

— Melina Abdullah -

Moral Appeals Aren't Enough

— Robin D.G. Kelley -

The Black Infinity Complex

— Shamell Bell -

Our Movement Is Global

— an interview with Alice Ragland -

Reflections After Ferguson

— Bob Hansman - Marxism and Art

-

Art and Aesthetics on the Left

— an interview with Andrew Hemingway -

John Reed Clubs and Proletarian Art--Part I

— Andrew Hemingway - Reviews

-

The Prophet Alarmed

— Alan Wald -

Drug War Winners and Losers

— Kevin Young -

A Window on Indigenous Life

— Waskar T. Ari-Chachaki -

Boricua's Revolutionary Inspiration

— Antonio Carmona Báes -

Capital Crimes of Fashion

— Sheila McClear -

Pioneers of Women's Liberation

— Nancy Holmstrom -

Life After Death for Labor?

— David Cohen

Kevin Young

Drug War Capitalism

By Dawn Paley

Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2014, 279 pages, $16.95 paperback.

THE DISAPPEARANCE AND likely massacre of 43 leftist students in Mexico’s Guerrero state in September 2014 has cast a spotlight on the deep ties between high-level state personnel and violent criminal forces in Mexico, as well as U.S. knowledge of those ties. Since then, ongoing protests and revelations have further undermined official justifications for the militarized “war on drugs.”

Most independent analysts concluded long ago that the U.S. approach to fighting drugs was a failure from the perspective of curbing both drug production and drug-related violence. The favored policies — heavy on militarization, criminalization and prisons, light on public health and economic alternatives — have greatly exacerbated violence in supplier countries while swelling prison populations in all countries touched by it.

Moreover, the war on drugs has always been profoundly arbitrary and hypocritical in the drugs it targets. Alcohol and tobacco contribute to far more deaths each year than marijuana, for example.

Why, then, does the model continue in full force? A big reason, argues journalist Dawn Paley, is that so-called drug wars have proven enormously profitable to large capitalists, and useful to powerful sectors of the state apparatus, in countries like Colombia and Mexico (and their primary foreign sponsor, the United States).

At a time when estimates of the death toll from drug-related violence in Mexico alone over the past decade range as high as 200,000, Paley’s analysis could not be more urgent. [A feature article in ATC 159 by Dawn Paley on “drug war capitalism” is online at http://www.solidarity-us.org/pdfs/Dawn.pdf — ed.]

Who Loves Drug Wars?

The dominant media narrative about drug violence in Latin America, notes Paley, is that it results from “in-fighting between the cartels that transport narcotics from Colombia through Central America and Mexico to the United States.” The U.S.-led war on drugs in the region, meanwhile, is often depicted as an earnest but “futile whack-a-mole game, where feisty criminals consistently outrun a series of multibillion-dollar military operations.” (26, 51)

State officials are portrayed as wholly separate from criminal groups. To the contrary, Paley shows that the worlds of state officials, large business interests and drug lords are in fact thoroughly integrated. Far from being inimical to business investment and the modern state, illicit drug economies and drug-related violence are simply a part of capitalism-as-usual.

For one thing, the drug economy is not separate from the rest of the business world. One of the problems with the term drug cartel is that major traffickers rarely confine themselves to just the illicit drug business: many also make profits through kidnapping, human trafficking, extortion, assassinations, intimidation of small farmers, and myriad legal business enterprises.

At the same time, capitalists with “legitimate” business interests in the legal economy often have direct financial stakes in illicit sectors or at least employ their services from time to time. One of Honduras’s richest capitalists, Miguel Facussé, traffics not just in biofuels but cocaine as well. And most drug money winds up in private banks, particularly in the Global North.

Pro-business government policies, meanwhile (often implemented alongside counternarcotics initiatives), facilitate the drug business in various way. Rising inequality generated by neoliberal policy “makes more people willing to risk working in the illicit economy,” while state-funded infrastructure like mega-highways can “also serve drug traffickers.” (49)

A similar affinity exists between state counternarcotics policies and capitalist profitmaking, which likewise tend to be mutually reinforcing. For example, drug war spending is a direct subsidy to private military and security contractors in the United States, Latin America, and elsewhere.

Within recipient countries, weaponry and training dispensed through the drug war strengthen both military and paramilitary forces, and “can be used for a variety of purposes” apart from drug control: massacring Mexican student activists, displacing peasants from lands rich in mineral or petroleum resources, and so on. (19)

Paley is not arguing that capitalists and state agents are intentionally stoking drug-related violence in order to justify a militarized state response that will facilitate profit-making. Reality is more complex, and the dominant narrative that blames “turf wars” among cartels is not entirely false.

But Paley does show that powerful segments of the capitalist class and the state benefit from both the illicit drug business and the militarized drug war model that has been adopted from Colombia to Mexico.

Colombia to Mexico and Beyond

Paley identifies “three principal mechanisms through which the drug war advances the interests of neoliberal capitalism” — through changes to legal and economic policy, through the funding of formal military and police forces, and through the strengthening of right-wing paramilitary groups. (219) These mechanisms are documented in the book’s four case studies of Colombia, Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras.

Colombia became the laboratory for militarized drug war policies under Plan Colombia, signed by Bill Clinton in 2000. The plan involved massive U.S. military aid and training, the aerial fumigation of crops, and virtual free reign to Colombia’s armed forces and right-wing death squads to target not only left-wing guerrillas but also nonviolent social movements, peasants living on coveted land, and thousands of expendable poor people murdered in order to inflate body counts.

The plan greatly intensified the transfer of wealth from poor to rich. The displacement of peasants increased during the term of far-right president Alvaro Uribe (2002-2010), paving the way for the usurpation of millions of acres of land. Economic policies implemented in conjunction with Plan Colombia included the partial privatization of the state petroleum company and generous contracts for foreign companies like BP and Drummond.

Legal reforms, meanwhile, cut resources for criminal defense and imposed lengthier prison sentences — though exceptions were made for armed actors who advanced capitalist interests. In 2001, the government estimated that right-wing paramilitaries “controlled 40 percent of the drug trade, while the FARC [the main guerrilla group] controlled just 2.5 percent.” (55)

The state’s quiet encouragement of the paramilitaries — notwithstanding their ostensible “demobilization” in the mid-2000s — suggests that combating drugs was at most a secondary goal.

If Plan Colombia was not mainly about fighting drugs, it did disrupt some drug traffickers. Their solution was to shift some of their activities northward to Mexico and Central America, in a predictable example of the “balloon effect.” The Colombia model was then adapted for use there.

Paley’s three chapters on Mexico examine the Mérida Initiative (“Plan Mexico”), under which the U.S. government has delivered nearly $3 billion in security aid. The results have been similarly gruesome.

Reforms to legal and economic policy have paralleled those seen earlier in Colombia. Prolonged detention of suspects is now permitted, the prison complex has expanded, and state torture has become endemic. In the past two years, the government of Enrique Peña Nieto has also pushed through a historic reform to Mexico’s state-owned oil company, designed to expand private corporations’ role in the industry.

Chapters 5 and 6 describe the intertwined processes of militarization and paramilitarization and how they facilitate the profitmaking of powerful capitalists.

Heavily-armed military and police forces are deployed to protect large companies, seldom showing such concern for small businesses, farmers or ordinary civilians. Indeed, the latter groups are routinely extorted and are targeted with violence if they resist armed criminal groups, the state or large capitalists.

Paley includes stories of communities that have resisted these forces, often paying a high price as a result. We hear, for instance, about two activists murdered in the northern state of Chihuahua for opposing a Canadian silver company.

We also learn about a community police force in Michoacán state that sought to protect its territory from both the government and the Knights Templar criminal organization. In the latter case, the community group was violently disbanded by state forces, after which the Knights Templar reentered the area, reestablished control of local iron mining, and began extorting residents.

The final two chapters, on Guatemala and Honduras, add more detail to the horrific but familiar pattern. Again state forces, large capitalists and criminal groups are deeply interconnected, a fact not negated by the states’ brutal counter-drug activities.

Once more, the discourse of the drug war provides a convenient pretext for the theft of land and resources. And yet again, the perpetrators in both countries benefit from hundreds of millions in U.S. military aid, in the form of the Central American Regional Security Initiative.

Further Questions

Drug War Capitalism is a much-needed analysis of how both the drug trade and the “war on drugs” help advance the interests of capitalist and state elites. Still, the book does seem to leave several questions inadequately explored.

First, the motivations behind state policymaking deserve further analysis. On the U.S. side, a more thorough review of government documents might have strengthened the book’s argument that capitalist motives help shape military and counternarcotics policy toward Latin America.

Some policy documents suggest an additional, related motive of U.S. military aid, one not analyzed in the book: to counter the influence of left-leaning governments. This geopolitical goal has helped shape U.S. drug policies in the past, leading Washington at times to fund military buildups in friendly states and at other times to directly abet narcotraffickers — for example, when the Reagan administration supported the crack cocaine trafficking of the Contra terrorist forces seeking to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua.

Domestic U.S. factors also merit more attention. Paley mentions the role of various corporate sectors (weapons contractors and big banks, especially) and state institutions in promoting the policies she documents, but which specific actors are influencing policy, and how? And how does the domestic war on drugs relate to U.S. sponsorship of drug wars abroad?

Within Latin America, are drug wars beneficial for all capitalists, even all large capitalists? At one point Paley mentions that tourism in Acapulco dropped 50% from 2006 to 2011. Have such effects sparked intra-capitalist class tensions, and with what effect on policymaking? The recent calls for limited decriminalization by some neoliberal politicians suggest that massive drug-related violence may be detrimental to at least some capitalist forces.

Finally, and maybe most important, what might be a better approach to confronting drug-related violence? Paley includes several suggestive stories of community-organized police forces. Might such forces offer an alternative for communities and local governments?

Paley wisely cautions that community police are not inherently just or democratic — after all, many vicious paramilitary groups cast themselves as locally-rooted “self-defense” organizations. In any case, such strategies are unlikely to succeed by themselves; any real solution to drug-related violence must confront the poverty and inequality exacerbated by neoliberalism as well as the impunity conferred (and enjoyed) by brutal, corrupt and plutocratic states.

Paley doesn’t claim to have written a comprehensive assessment; her main focus is the drug wars’ impact in the four countries studied. These questions are intended less as critique than as extensions of the book’s analysis, which is incisive and timely.

July-August 2015, ATC 177