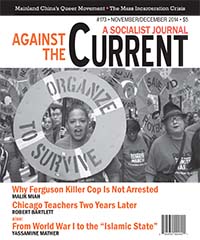

Against the Current, No. 173, November/December 2014

-

The Middle East's "World War"

— The Editors -

Why a Killer Cop Is Not Arrested

— Malik Miah -

Two Years After the CTU Strike

— Robert Bartlett -

Mass Incarceration and the Left

— Heather Ann Thompson -

What September 21st Showed

— Dianne Feeley -

Family Planning and the Environment

— Anne Hendrixson -

Egypt: Protesting Injustice

— Noha Radwan -

Mahienour al-Masry: Icon of a Revolution

— Noha Radwan - The Purge of Steven Salaita

-

From Sykes-Picot to "Islamic State": Imperialism's Bloody Wreckage

— Yassamine Mather -

LGBT Activism in Mainland China

— Holly Hou Lixian - Hong Kong's Umbrella Upheaval

-

The Two-Party System, Part I

— Mark A. Lause - Reviews

-

Literature in the Shadows

— Bill V. Mullen -

Anti-Imperialist Dreamwork

— Matthew Garrett -

AIDS Then and Now: A Blood-Drenched Battlefield

— Peter Drucker -

Documenting European Socialism

— Ingo Schmidt -

Louis Althusser & Academic Marxism

— Nathaniel Mills - In Memoriam

-

Ruby Dee, 1922-2014

— Judith E. Smith -

Claudia Morcum, Civil Rights Righter

— Dianne Feeley & David Finkel -

Notes to Our Readers

— The Editors

Matthew Garrett

Geographies of Liberation:

The Making of an Afro-Arab Political Imaginary

By Alex Lubin

Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014, xiii, 233 pages, $29.95 paperback.

INTERNATIONAL SOLIDARITY HASN’T had a particularly good run recently, at least viewed from North America. The energy of the Occupy movement still circulates, but the sequel of the 2011 events remains uncertain, and the yield of the Arab Spring — never really a trans-hemispheric movement, in any case — is perhaps more ambiguous than ever.

Despite the glowing circuits of transnational social media, the committed internationalist is justified in wondering if the confident calls to arms of the past two centuries (“of all nations!”) were uttered only in a dream.

One comes then to Alex Lubin’s book about transnational political imaginaries with high hopes but diminished expectations. The cover image of Malcolm X and Ahmed Shukairi of the Palestine Liberation Organization, in Egypt in 1964, promises a lot. And the title provokes an anticipatory question: What sort of political imaginary was made — or is in the making — in the activity of Arab, African, and African American movements?

Yet despite its author’s enthusiasm for the political links between African Americans, Palestinians, Arabs and Israeli Jews, the book is less a study of actualized political imaginaries — that is, shared and self-conscious organizational solidarities — than it is a broad sketch of missed or partially completed connections between vanguard intellectuals (and artists) in Africa, the Middle East, and the United States.

At the same time, Lubin insists that the book is really about “the fugitive memories of history that have become taboo in the contemporary public sphere…African American engagement with Palestine and Israel…is shaped more by a global history of nationalism and racialization than merely by U.S. interethnic rivalries.” (174)

In excavating those buried relations, Lubin, who teaches American Studies at the University of New Mexico and directs the Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for American Studies at the American University in Beirut, relies on the explanatory force of context. Geographies of Liberation is oriented toward those moments when “subjects imagine new futures within contexts not of their making.” (173)

Those futures are severely circumscribed in Lubin’s telling. If there is hope — not just of success, but even of realized collaboration across geographical and situational borders — it is the wishful kind that comes from dreaming rather than the hard-headed stuff of organizational or political gains.

On one hand, this approach might indicate a radical’s commitment to a realist accounting of the situation in which political activity takes shape. On the other hand, it also encourages the political archaeologist to look away from his recovered materials and toward the accounts of the context that have been given by others.

At times, Lubin’s reliance on extrinsic accounts of the “context” leaves his reader wishing for readings more alive to the contingency of historical events, a little less sure that every outcome was determined from the start.

Flood, Nakba and Diaspora

The history in this book, then, happens predominantly behind the backs of the historical actors. In itself this is no criticism of Geographies of Liberation, which is most impressive when Lubin sensitively scans his materials for glimmers of action.

For example, the book’s final chapter shines brightest when it turns to Palestinian appropriations of African-American hip hop and poetry, particularly in a brief assessment of the way the Palestinian-American poet Suheir Hammad reworks the concept of refugee in her poem addressing the Katrina disaster.

Flood and nakba are joined in Hammad’s poem, which according to Lubin “unearth[s] a structure of feeling, a sense that the geographies of colonial modernity are broken, as the U.S. state’s ‘protections’ of citizenship and the UN’s creation of the State of Israel are both exposed as violent ruptures.” (169)

That last sentence suffices as a summary of the political situation, but it leaves something to be desired as a reading of the poem itself. And here, on the question of receptivity to its chosen materials, one might consider the book’s overall approach.

The wide range of Geographies of Liberation, which reaches from the 19th-century American fascination with the Holy Land to the gloaming of neoliberalism in our time, seems sometimes to desensitize the book to the complexity of its various subjects. As a result, Geographies of Liberation will be of greatest interest to readers more drawn to the general pattern of the quilt than the details of its component swatches.

The first chapter outlines African-American representations of Palestine as the Holy Land, zeroing in on the “Afro-Zionism” that figured Liberia as a kind of Jerusalem.

W. E. B. Du Bois becomes the great emblem of both the promise and the limitation of this position, based on a shared (Jewish and African American) “politics of diaspora” (46). What Lubin describes is precisely the moment when African-American history was assimilated to Jewish history, and in which the term “diaspora” was made freshly available for application to a whole world of ethnic and racial experience beyond its original use.

After this foundational description of 19th-century innovations of what (in another idiom) we might call psychogeography, Lubin delivers three exceptionally important case studies. The first is an account of Dusé Mohamed Ali’s peregrinations across zones of Afro-Arab solidarity: from the African Times and Orient Review (in 1911) all the way to work within the nationalist movement of Marcus Garvey and the formation of a sovereign Egypt.

Born in Alexandria in 1866, Ali lived what Lubin calls a “Zelig-like life” (51), fleeing Egypt after the 1882 British bombardment, living in London as an actor and journalist until 1921, and traveling globally after the 1890s, including on an American tour that identified him as “The Young Egyptian Wonder Reciter of Shakespeare.”

Ali worked and wrote for the Fabian New Age in London, which stirred his political consciousness. Lubin tells us that Ali was radicalized by the Universal Races Congress in 1919, for which he performed the third act of Othello, and at which he was given a copy of W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk.

Ali hated Du Bois’ book, which he saw as the work of an “Afro-American academic idler,” but Lubin points out that the event itself was “precisely the sort of transnational gathering that made his own complex history intelligible.” (53) The yield of the Congress, for Ali, was a properly “internationalist black consciousness,” though one that “emerged as a consequence of imperial change.” (70-71)

What Ali finally lacked, according to Lubin, was “a revolutionary political theory with which to understand imperialism.” (76) The best Ali could do — not too bad by early twentieth-century standards — was to produce a cultural-pluralist approach within the Afro-Arab world.

The Ralph Bunche Story

Lubin follows his account of Ali with a chapter on Ralph Bunche, the UN hack whose split-second flirtation with Marxism is given too much weight by the chapter title “Black Marxism and Binationalism.”

Lubin is a careful student of Bunche, posing to his biography the greatest question of all: “How did Ralph Bunche, who in the 1930s analyzed the Negro question in terms of racial capitalism and colonialism, become recognized by the 1950s as the champion of the ability of the nation-state (United States and Israel) to address problems of racial minorities?” (81)

Perhaps an answer lies in Bunche’s eagerness to align himself with the strongest institution available, whether that was the Communist Party, the National Negro Congress — which united him with A. Philip Randolph and John P. Davis — or the UN itself. (Bunche’s 1930s essay “Marxism and the Negro Question” is little more than rote popular-front material — although it must be admitted that the Communist Party’s insistence upon the thousand threads connecting imperialism and U.S. racist capitalism was, intellectually, one of its most robust.)

In any case, Lubin’s real story here is double: the changing winds of Bunche’s position help to inform the collapse of the binationalist approach to Palestine/Israel in 1947-48, not least because of his own role. (Bunche was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950 in honor of his work toward the armistice that punctuated the Arab-Israeli war of 1947-48.)

What was eclipsed by 1947, among other things, was previous Communist orthodoxy, insofar as binationalism was the policy of the Palestinian Communist Party — itself abandoned when the Soviet Union, just after the United States, turned to support the foundation of Israel. Lubin reports but does not dwell on this uncanny moment of Cold War coziness between superpowers.

Lubin seems to strain at times to avoid a negative assessment of Bunche, whose desperation to operate close to power (and white power, at that) is all too evident. Bunche is not alone in having traveled from Popular Front organizations to the Office of Strategic Services (forerunner of the CIA) and the U.S. State Department, but the continuous line of his institutional politics is clearer than any evidence of substantive intellectual or political transformation.

Indeed, when Lubin reports almost as an aside that Bunche took a seminar on comparative cultures at the London School of Economics with Bronislaw Malinowski, one pants at the prospect of finding out if Bunche learned anything at all from the great anthropologist. That Lubin can only tell us that while in London, Bunche “interacted” with Jomo Kenyatta and Paul Robeson, supplies something like an answer: neither intellectual curiosity nor political conviction were ever among Bunche’s strongest suits. (84)

Panthers and Palestine

One can almost feel Lubin’s sigh of relief when Geographies of Liberation turns to the Black Panther Party and the PLO, in the book’s penultimate chapter. For the material itself seems to invite a more robust engagement than in the preceding sections. The chapter triangulates the Panthers with the PLO and with the Israeli Black Panther Party.

That the American Panthers in their later phase shared an anti-imperialist orientation with the PLO will hardly be news to students of the Panthers (particularly those who have read Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Jr.’s Black against Empire, reviewed in ATC 168, http://www.solidarity-us.org/node/4072). But Lubin’s chapter sheds fresh light on the situation by considering the fate of the Israeli Panthers.

The Israel Black Panthers group was founded by Mizrahi Jews (from Arab and North African countries) to, as Lubin puts it, “analyze and resist the conditions of imperialism and racial capitalism in Israel during the first half of the 1970s.” (131)

Never as radical as the U.S. Panthers, the Israeli party nevertheless drew sorely needed attention to the condition of the Mizrahim in Israel, and Lubin’s study traces the extraordinary contradictions this formation faced as the Israeli Black Panthers “began to reconfigure their belongings in Israel…to see commonalities not only with black anticolonialists in the U.S. but also with the national liberation struggle of the Palestinians, even though Mizrahi Jews were, to Palestinians in Israel and in the West Bank and Gaza, the oppressor.” (139)

The cleverness behind this movement is still legible in Lubin’s quotation of Reuven Abergil’s spoof manifesto for a Mizrahi right of return, 40 years after the period of his work with the Israeli Panthers. Although as Lubin notes, the radical edge of that earlier moment looks sharper in retrospect, something of its wit remains in Abergil’s proposal:

“I hereby turn to the heads of the Arab and Muslim countries…I wish to propose a…law that would provide for a ‘right of return’ of Jews from Arab and Muslim countries back to their homelands, financed by the property of our ancestors that was left behind in these countries, in order to facilitate settling in after 60 years of imposed exile, and to encourage support for this idea amongst other leaders and people…

“If the gates will open in Arab and Muslim countries for the Jews to return home, the 40% of the Zionist Europeans will lose the ‘demographic security’ we provided them, in addition to the ‘black laborers’ who served them, and they will have to learn to act as a minority amongst the Arab majority, or return to their own homeland, as most of them have a second passport anyways.” (140)

The absurdity and utopianism are, of course, the root of Abergil’s joke — but also part of the politics. The point is to put the Mizrahim in relief in such a way as to unsettle the simple binary of Arab/Israeli. That may be taken as a procedural point for Lubin’s book, too, which is above all committed to pluralizing our current geopolitical imaginary.

Still, in Geographies of Liberation liberation is clearly on its back foot, and it will be up to others to work through a conjunctural analysis capable of politically reenergizing the nexus of questions Lubin smartly ties together here: the linkage of “the Palestine question to a moral horizon that includes the ‘Jewish question’ and the ‘Negro question.’” (174)

November/December 2014, ATC 173