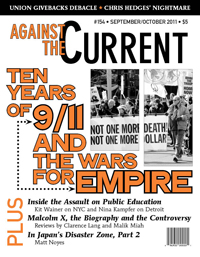

Against the Current, No. 154, September/October 2011

-

The Years of 9/11

— The Editors -

9/11 and the Clash of Atrocities

— John O'Connor -

Ten Years Later: We're Less Free

— Julie Hurwitz -

On 9/11 and the Politics of Language

— an interview with Martin Espada -

Alabanza: In Praise of Local 100

— Martin Espada -

To Rebuild Teamster Power

— an interview with Sandy Pope -

Bloomberg and NYC's Education Wars

— Kit Adam Wainer -

Detroit Public Schools: Who's Failing?

— Nina Kampfer -

The Catherine Ferguson Struggle

— Nina Kampfer -

Givebacks in a Deepening Crisis

— Jack Rasmus -

Letter from Tokyo: In "The Zone" of Disaster

— Matt Noyes - On Marable's Malcolm X

-

Manning Marable and Malcolm X: The Power of Biography

— Clarence Lang -

Evolution not "Reinvention": Manning Marable's Malcolm X

— Malik Miah - Reviews

-

Exploring Imperial Pathologies

— Allen Ruff -

Introduction to Is There a Human Future?

— David Finkel -

Chris Hedges' Vision & Nightmare: Is There a Human Future?

— Richard Lichtman -

The Fate of Vietnam's First Revolution

— Simon Pirani -

Bolshevism, Gender & 21st Century Revolution

— Ron Lare - In Memoriam

-

David Blair, Detroit Poet, 1967-2011

— Kim D. Hunter

John O'Connor

RESPONDING TO THE terrorist attacks of September 2001, Against the Current’s “Letter from the Editors” (#95, November/December 2001) made an impassioned plea that the alternative to war was a political movement for social justice. Like many on the left, the editors pointed out that only an agenda for social justice could save the people of Afghanistan and Iraq from America’s military wrath and help curb the attraction of individual terrorist solutions.

As we all know, after just three weeks of preparation, America’s “war on terror” was unleashed. The struggle to influence the U.S. response was unsuccessful, not because people desired war, but for the simple reason that the New York/Washington carnage offered ruling elites a unique political opportunity. The Bush administration — originally awash in electoral illegitimacy and political confusion — embraced Randolph Bourne’s ironical maxim that “war is the health of the state.” (Bourne was a critic of U.S. involvement in World War I.)

During the course of the “war on terror” the authoritarian potential of the democratic state was set free. The American military invaded and occupied Afghanistan and Iraq, at the same time that large segments of the U.S. population were coerced into a flagwaving herd and others persecuted because of their race and/or religion.

Ten years on, with Osama bin Laden summarily executed and the United States engaged in talks with the Taliban, it is important to revisit and untangle some of the foreign and domestic issues associated with 9/11. Although it has become cliché to argue that 9/11 “changed everything,” it is true that Al-Qaeda’s terrorist attack was a defining moment in recent American history.

Al-Qaeda’s attack and Washington’s response have generated a number of important challenges and lessons for the revolutionary left, especially as it struggles to remain relevant in the 21st century.

Theoretically and politically, 9/11 has forced the left to reflect on the nature of imperialism today. And it has forced the left to assess the successes and failures of both the Global Justice and antiwar movements. Thinking about these issues is essential if we are going to rebuild the left.

Similar to the Cold War, a whole generation of young Americans (i.e. today’s 20-year olds) have come of age politically during a time in which world affairs were, once again, reduced to a simplistic struggle between good (us) and evil (them).

Competing Atrocities

The terrorist attack on the United States was savage and brutal, taking the lives of thousands of innocent working people. Very quickly the Bush administration chose to militarize a criminal act, claiming that “our very freedom” was under attack. In putting the country on a war footing, Bush in his 9/11 address promised to “defend freedom and all that is good and just in our world.”

The refusal to ask what contributed to the events of 9/11 helped fuel all sorts of crazy conspiracy tales (e.g. it was an inside job, Israeli agents were responsible). A significant proportion of Americans can speak more about WTC building #7 than the origins of Islamic fundamentalism.Yet Al-Qaeda’s attack was what the CIA called “blowback” — an unintended consequence of America’s past policies and actions of global domination.

The U.S. response was designated “Operation Enduring Freedom,” and the Bush administration waged war on the Afghan people, terrorizing civilians with cruise missiles and the non-stop bombing of Afghan cities. In a matter of weeks, Washington chased the ruling Taliban out of Kabul as it scattered the Al-Qaeda hierarchy. With the appearance of “victory” secured (a client regime in place and Afghan women now officially free), the United States looked toward Iraq.

Bush used his 2002 State of the Union address to outline a further threat to world peace — the “axis of evil” (i.e., the terrorist-supporting regimes of North Korea, Iran, and Iraq). Focusing on unfinished family business and a dream to democratize the Middle East, Bush extended his war on terror toward a new front.

In March 2003, after pounding the country from the air, American troops invaded Iraq and toppled Saddam Hussein’s regime within 21 days. Although Hussein had been contained and eliminated as a regional power since the early 1990s, the United States aimed to disarm Iraq of its weapons of mass destruction (never found), to end Saddam Hussein’s support for terrorism (never proven), and to free the Iraqi people (who never asked for our help).

The scale and violence of the American reaction to 9/11 has been hard to fathom. Although human and financial costs vary from source to source, no one really knows how many people have been killed in Afghanistan and Iraq. One recent report details that the financial cost of these wars will total anywhere from $3.2 to $4 trillion dollars, and that approximately 7.8 million people have been displaced from their homes, the equivalent of everyone living in Connecticut and Kentucky being forced to flee their residences. (http://costsofwar.org)

America’s “war on terror” has had little to do with national security. Instead, the United States committed an atrocity on the Afghan and Iraqi people — two populations that had nothing to do with the 9/11 attack. In responding to 9/11 with an atrocity of its own, the Bush administration gave a green light for the Russians to step up their campaign against the Chechens, and Ariel Sharon to escalate Israel’s war on the Palestinians — all in the name of combating terrorism.

Neoliberal Imperialism

The fact that 9/11 was both a moment of clarity and of possibility was articulated by National Security Advisor Condoleeza Rice, who in an April 29, 2002 speech at Johns Hopkins University, argued that the international system had been in flux since the Cold War — but 9/11 represented an “enormous opportunity…to create a new balance of power that favored freedom.”

With the release of the September, 2002 National Security Strategy (“the Bush Doctrine”) the contours and agenda of this new balance of power were defined. This infamous document — influenced heavily by the neoconservative “Project for a New American Century” — promised peace and prosperity through American force and free markets. In making veiled threats toward Russia, China, and “failed” states everywhere, the Bush Doctrine brazenly asserted that the United States would not hesitate to act alone and pledged that “our forces will be strong enough to dissuade potential adversaries from pursuing a military build-up in hopes of surpassing, or equaling, the power of the United States.”

Being one part saber rattling and one part justifying the invasion of Iraq, it is important to note that the National Security Strategy document was really an exercise in crisis management. Of course, the problem was not Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction, but was the real and perceived erosion of U.S. hegemony vis-à-vis neoliberal capitalism.

Marxist political economy provides a theoretical lens which enables one to see both the contours of accumulation within a given historical moment, and the different ways accumulation is transformed over time. It also offers a framework for understanding world politics, especially the hierarchy of states that give structure and coherence to an unevenly developed world economy.

As capitalism has changed, so too has imperialism. Political forms of domination always correspond to capitalist accumulation — this was seen during the colonial conquest of classical imperialism, the inter-imperialist conflict of monopoly capitalism, and post-World War II superpower imperialism. Within each phase imperialism, as a system of global governance, configures both the relationships across different nations (developed vs. developing) and among similar countries (the advanced capitalist world).

The Cold War marked the height of U.S. ability to shape and dominate the international capitalist order. It was a moment of super-imperialism, in which all other capitalist states were dominated by the United States. Yet the neoliberal restoration of profitability in the 1980s — with its sustained attack on the working class, unbridled capital mobility, and state restructuring — produced a form of imperialism that has been complicated and evolving.

Early on, under Reagan, the establishment and management of neoliberalism depended upon this American super-imperialism — that is, if a country threatened to delink, the United States would intervene militarily (as it did in Latin America in the early 1980s) and the World Bank/IMF pushed free-market policies (the Washington Consensus). By gun and by loan, the initial spread of neoliberalism was dictated by Washington.

Despite the collapse of the Soviet Union and the demise of independent nationalist movements, two events supposedly marking the pinnacle of American power and influence, neoliberalism itself contained dynamics that further transformed global politics. This transformation rests on three distinct, but interrelated issues.

First, the neoliberal period has been defined by the expansion and development of market-relations globally via the growing interconnectedness between different parts of the world. Trade, foreign direct investment, and finance have all linked together the transitional economies of the East, the resurgent Asian economies, the European Union, and so on. The world economy today is much more complex than that seen in the past.

Second, as a solution to the profitability crisis, neoliberalism has been overwhelmingly socially regressive. That is, profits have come at the expense of jobs, wages, and economic growth; private appropriation has been privileged over the meeting of social needs. As such, neoliberalism has been resisted in different ways, in different places.

Third, the long-term sustainability of neoliberalism has been no sure thing. From the very beginning, neoliberalism has been an inherently unstable political project, largely due to the vulnerability associated with overexposure to financialization. Neoliberalism has staggered from one financial crisis to another, with debt defaults (Mexico in 1982 and 1994), stock market crashes (1987, 1989, and 1994), monetary instability (the EMS crisis of 1992-93), and regional/national meltdowns (the 1997 Asian debacle, 2001 Argentina) being prime examples.

Because of these different foci of accumulation, opportunities for resistance and persistent crises, neoliberal imperialism has evolved from a form of American super-imperialism to a kind of ultra-imperialism in which a coalition of capitalist states are responsible for the unity and operation of the capitalist system. There is no doubt that the political governance of neoliberalism is embedded within a collection of institutions, such as the United Nations, G-8, the World Bank/IMF, the European Union and the World Trade Organization.

With control of and access to markets more important than the command of territory, neoliberalism’s management has occurred through a system of rule-based multilateralism. Although this had some effect of undermining American hegemony, the success of neoliberalism is that it locked states (be they Brazil, South Africa, Italy, Russia, etc.) into its own structures. Countries would rather be included in its coercive logic (regardless of the costs) than excluded. The shift from super-imperialism to ultra-imperialism illustrates that the spread of neoliberalism has been more consensual than we would like to believe.

The Empire Strikes Back

The tragedy of 9/11 has forced the left to re-examine the nature of neoliberal imperialism. Whereas Bush (Sr.) and Clinton (more or less) played by the multilateral rules, even going so far as to build alliances and coalitions during the first Gulf War and the NATO intervention in Kosovo, George W. Bush was not enamored with the multilateral management of global neoliberalism.

Prior to arriving in the White House, the war hawk Condoleezza Rice defended American national interest by writing that “…multilateral agreements and institutions should not be ends in themselves…the Clinton administration has often been so anxious to find multilateral solutions to problems that it signed agreements that are not in America’s interest.” (“Promoting the Nationalist Interest,” Foreign Affairs 79, 2000)

Once in office, Bush selectively rejected the rules and institutions of multilateralism. He refused to cooperate on a number of arms limitation treaties, was hostile toward the International Criminal Court, and would not agree to the Kyoto treaty on global warming. By 2002, Bush ignored the trade rules of the WTO and imposed a protective tariff on the American steel industry.

U.S. concerns over multilateral neoliberal management were tied to its diminishing hegemony over the world economy and the other capitalist countries. The uncontested economic and ideological dominance of the United States declined as neoliberalism progressed. While still powerful, American technological leadership, the superiority of its output, its competitive standing on the world market, and the primacy of its foreign direct investment had all eroded and declined. Most important, the dollar’s role as the international currency had slipped.

The 2002 National Security Strategy document and the invasion of Iraq had more to do with reasserting American hegemony and compensating for economic decline than any terrorist threat. The two major dangers to American hegemony were seen as an independent and autonomous European Union (and its euro) and the future development of China.

Given the complexity of neoliberalism and the loss of American hegemony to influence the international order, Bush’s decision to invade Iraq can be seen as a deliberate attempt to use military power to further American economic interests. Although it had the opposite effect in hindsight, the invasion of Iraq was an attempt to remake American hegemony through coercion, relying on the one asset that has not diminished — the U.S. military.

The Bush administration moved to swing the political pendulum back towards American super-imperialism. Strategic control over Middle Eastern oil was an attempt to do that and it was a way to influence the rules and operation of neoliberal institutions. The destruction of Afghanistan and Iraq was not done out of political economic strength, it was done out of weakness.

The justification of American unilateralism in Afghanistan and Iraq, as the National Security Strategy makes clear, was that American values are “universal values.” By destroying Al-Qaeda’s camps and removing the Iraqi dictator, the United States was claiming to ensure our common security, our common freedom — Bush and his minions were making the case that the United States can still act on behalf of world-wide capitalism.

Yet the question remains whether America’s failed actions in the Middle East will revive inter-imperialist rivalries, and escalate conflicts that will lead to new wars. With Middle Eastern oil such a strategic commodity, American attempts to control of Iraqi oil reserves does harken back to earlier days.

Lessons of the Movements

Starting with the 1999 “Battle in Seattle” protest, there has been a steady confrontation with the architects and institutions of neoliberal capitalism. This resistance found its expression in a renewal of social movements that contested capital’s right to exploit people and resources. The Global Justice movement (GJM) has been international in its nature, broad in its critique of society, and diverse in its makeup. In resisting neoliberal globalization, the GJM has raised political consciousness and set free a new spirit of self-emancipation.

Prior to 9/11, from Spring 2000 through the Summer 2001, there were major demonstrations in Washington (directed against the IMF/World Bank), Melbourne (World Economic Forum), Prague (IMF/ World Bank), Nice (European Union), Quebec City (Free Trade Area of the Americas), Gothenburg (European Union), and Genoa (Group of 8). It was estimated that in all hundreds of thousands of demonstrators — students, trade unionists, socialists, anarchists, environmentalists, feminists, anti-racists — participated in these confrontations with capital. Central to each protest were the consequences of neoliberalism on workers, women, the environment, and the poor.

The GJM’s international “summit-hopping” phase, as it was called in some quarters, came to an end when a number of world, regional, and local social forums were organized. These social forums were instrumental in establishing the antiwar movement.

Resistance to Bush’s war grew slowly (but steadily) as the attack on Afghanistan progressed and planning to invade Iraq commenced. The European Social Forum (ESF) in Florence played an important role in strengthening the GJM with its unambiguous rejection of capital’s regressive agenda of war and neoliberalism. With action against Iraq moving forward, the Florence ESF ended with a mass antiwar demonstration of close to a million people. Delegates to the forum agreed to a day of action on February 15th that turned out to be the largest peace demonstration in history.

An estimated 30 million people opposed to the impending war with Iraq took to the streets. Prior to and after February 15th, antiwar actions spread across many nations, making the case that the slogan “Another World is Possible” also applied to Western aggression in the Middle East.

The GJM has been a brilliant success, politicizing millions of people across the globe. And there have been a number of political accomplishments — summits were disrupted, meetings cancelled, trade negotiations moved. The emergence and development of the GJM also helped the revolutionary left to re-emerge from a long period of defeat and demoralization.

However given the scale of the GJM, concrete political victories have been scarce — the neoliberal order has continued to stagger along. And the antiwar movement was not able to stop the assault on Iraq. The major 2003 antiwar demonstrations in the United States, Britain, Italy, and Spain did not extract a political price in those countries. Popular anger against war was not enough to win political victories at either the international or domestic level.

Although much more work needs to be done to draw a political balance sheet of both the GJM and the antiwar movement, such an analysis is important in revitalizing the left. There are a number of important questions associated with the antiwar movement that need to be considered: Why was it so difficult to sustain the movement? What were the anti-imperialist politics of the movement? And how did electoral concerns, organization and strategy/tactics impact the movement.

Moving Forward

9/11 was an atrocity that was met with an atrocity. It provided the Bush administration with an opportunity to fortify American hegemony in hopes of changing the global management of neoliberalism. It was the people of Afghanistan and Iraq who defeated Bush’s imperial agenda at a horrible cost, leaving Bush and Obama to declare victory and scramble for ways to get out.

Post-9/11 the United States is in a much weaker place than it was before it. Internationally, U.S. leadership has been severely damaged and its military power was shown that it is not invincible. Domestically, flag-and-ribbon-inspired unity was short-lived, with the country today being more polarized than ever.

With neoliberalism in (terminal?) crisis, the Middle East being transformed by popular movements, and Wisconsin in revolt, once again the ideas of Democrats and Republicans stand discredited. But 9/11 and its aftermath illustrate that rebuilding the left is not a luxury, it is a necessity.

Neoliberal imperialism can only be defeated through a project of the left built upon principles and action. Because the left only really exists to the extent that people accept its critique and agenda for change, there needs to be less political rhetoric and more political organizing.

September/October 2011, ATC 154