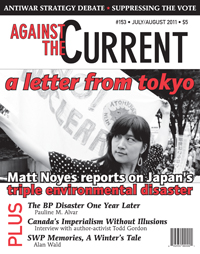

Against the Current, No. 153, July/August 2011

-

Austerity and U.S. Decline

— The Editors -

A Whiff of Jim Crow

— Malik Miah -

One Year of the BP Blowout

— Pauline M. Alvar -

Tokyo Letter: After the Disaster

— Matt Noyes -

What Did They Know...?

— Matt Noyes -

Canada's Imperialism Without Illusions

— ATC interviews Todd Gordon -

Brief Theory of the Present Crisis

— Hillel Ticktin -

Remembering the Paris Commune

— K. Mann -

Women in the Paris Commune

— Dianne Feeley -

A Winter's Tale Told in Memoirs

— Alan Wald -

Education Over Incarceration

— Luis Gonzalez - Dialogue

-

A Comment on Antiwar Strategy

— David Finkel -

A Rejoinder on Antiwar Strategy

— David Grosser - Reviews

-

Drugs, Race & the Gulag Industry

— James Kilgore -

Thinking About Equality

— Bill Smaldone -

The SEIU as Case Study

— David Cohen -

The Union in Academia

— Dan Clawson - In Memoriam

-

Leonard Irving Weinglass

— Michael Steven Smith -

Remembering Manning Marable

— Elizabeth Kai Hinton -

Gil Scott Heron

— Kim D. Hunter

Michael Steven Smith

LEN WAS NOT a ’60s radical. He was something more unusual, a ’50s radical. He developed his values, critical thinking and world view in a time when non-conforming was rare. He told a newspaper interviewer in Santa Barbara in l980 that “I would classify myself as a radical American. I am anti-capitalist in this sense — I don’t believe capitalism is now compatible with democracy.”

The third of four children, Leonard Weinglass grew up in a Jewish community of 200 families in Bellville, N.J. and attended high school in nearby Kearney, where he was a star end on the football team and Vice-President of his high school class. He went on to George Washington University in D.C. on a scholarship.

Len was an outstanding student and was accepted in l955 into Yale Law School. There was a story that he liked to tell about his college job, running an elevator at the Senate Office building. Lyndon Johnson was cold and rude to Len when riding in his elevator car. The one Senator who was friendly and who chatted with Len and always inquired as to how he was doing was — Richard Nixon, whom Len was later to confound by winning a dismissal for Daniel Ellsberg and Tony Russo in the historic Vietnam-era Pentagon Papers case.

Len went from Yale in l958 directly into the Air Force. Len was a lawyer in the Judge Advocate General’s Corp and rose from a second lieutenant to the rank of captain. The Air Force had charged a Black airman with some sort of crime. Len was assigned the case and got him acquitted.

This infuriated the brass, which was used to exerting its command influence over the results of military trials. They had Len transferred to Iceland, of all places. Why Iceland? Because it’s a country entirely populated by white people. There are no non-white genes in their DNA pool (drug companies for this reason use Iceland to test drugs).

Len cooled his heels until he was discharged, learning Icelandic in the meantime so he could speak directly to the judges there without an encumbering translator. When he arrived in an Icelandic court for his first trial the steps leading up to the building were lined with spectators. He asked his driver why? They wanted to see Len. They had never seen a Jew before…

He was discharged from the Air Force in l961 and set up a one-man law practice in Newark, New Jersey. When interviewed by The New York Times for Len’s obituary, Len’s friend and law colleague Michael Krinsky (Len was of counsel to the firm Rabinowitz, Boudin, Standard, Krinsky and Lieberman of New York, NY) said he considered Len “a modern day Clarence Darrow.”

Newark in Krinsky’s words “was a rough place to be. A police department and a city administration that was racist and as terrifying as any in America, and there was Lenny representing civil rights people, political people, ordinary people who got charged with stuff and got beat up by the cops. He did it without fame or fortune, and that’s what he kept doing, in one way or another.”

He did it for 53 years, being admitted to the bars in New Jersey, California and New York. We all know of Len for his famous legal work in the Chicago Seven case with Abby Hoffman, Dave Dellinger and Tom Hayden during the Vietnam War period. We remember his expertise in advocating for death row inmate Mumia Abu-Jamal.

He finally got his friend Kathy Boudin out of prison after 23 years. He represented Puerto Rican independentista Juan Segarra for l5 years. In the Palestine 8 case, where the defendants were charged with aiding the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, he was part of a team which stopped their deportation. That took 20 years.

“Conspiracy” and Terror

The Cuban Five case was Len’s last major case. He worked on it for years up to the time of his passing, even reading a court submission from his bed in Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx. The case highlighted what Len considered the U.S. government’s hypocrisy in its “war against terror.”

Len came in at the appellate level after the Five had been convicted by a prejudiced jury in Miami. His client Antonio Guererro and the others were found guilty of “conspiracy to commit espionage” against the United States sometime in the future.

The Cuban Five were sent to Miami by the government of Cuba to spy, not on the United States, but on the counter-revolutionary Cubans in Miami who were launching terrorist activities from Florida directed at persons and property in Cuba. They gathered information on the Miami-based terrorists’ murderous activities and turned it over to the FBI.

They asked the U.S. government to stop the terrorists, who were targeting the Cuban tourist industry by planting bombs at the Havana airport, on buses and in a hotel, killing an Italian vacationer. But instead the U.S. government used the dossier to figure out the identities of the Cuban Five, had them arrested, prosecuted, convicted and sentenced to long prison terms.

What Len said about the use of the conspiracy charge is illustrative of his precision and clarity of thought:

Conspiracy has always been the charge used by the prosecution in political cases…. In the case of the Five, the Miami jury was asked to find that there was an agreement to commit espionage. The government never had to prove that espionage actually happened. It could not have proven that espionage occurred. None of the Five sought or possessed any top secret information or U.S. national defense secrets.

Len was drawn to men and women accused of doing extraordinary acts of bravery and resistance, from Anthony Russo, who was charged along with Daniel Ellsberg in the Pentagon Papers case, to Angela Davis and many others [a list appears in the full-length version of this tribute].

Len kept his sense of humor even during those terrible final days at Montefiore Hospital. His surgeon abandoned his attempt to remove what turned out to be a large spreading malignant tumor, undetected by the pre-op CT scan. When the surgeon saw what it really was, an inoperable tumor, he could do nothing but sew Len back up and tell him the bad news.

Len looked up at us from his bed in the recovery room after being informed by the surgeon, assessed the situation and said simply, “summary judgment.” And so it was.

He lived but another six weeks, steadily declining, never getting to go home, never giving up, even as several doctors told him “you are in the final stretch.”

Len died in the evening of March 23, 2011 as spring was approaching in New York. He had plans to celebrate Passover in April, as usual, with his family in New Jersey. He knew quite a lot about Passover, led his family’s observance at the seder every year, and kept up a file on the holiday. He liked the idea that the Jews had the chutzpah to conflate their own flight from slavery with spring and the liberation of nature.

He had plans to tend his fruit trees on the side of the hill next to his Catskill cabin. He would have put in a vegetable garden near his three-block long driveway, which frequently washed out and which he repaired with sysiphean regularity. He would have set out birdseed on the cabin’s porch rail, where he would sit in a lounge chair on a platform and watch the songbirds feed.

He will be remembered personally as a good, generous and loyal friend, a gentle and kind person; politically as a great persuasive speaker, an acute analyst of the political scene, and a far-seeing visionary. “Lenny cannot be replaced,” wrote his friend Sandra Levinson. “There are no words for the loss we all feel. Do something brave, put yourself out there for someone, fight for someone’s dignity, do something to honor this courageous just man.”

July/August 2011, ATC 153