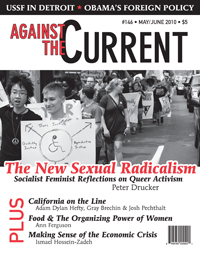

Against the Current, No. 146, May/June 2010

-

Who's Dysfunctional Now?

— The Editors -

U.S.-Israel Crisis: The Test

— David Finkel, for the ATC Editors -

Race & Class: Obama & the Politics of Protest

— Malik Miah -

U.S. Social Forum in Detroit

— Dianne Feeley -

The Death of NUMMI

— Barry Sheppard -

Obama's Imperial Continuity

— Allen Ruff -

Ohio Socialist Runs for U.S. Senate

— Dan La Botz -

Islamophobia Sets the Terms

— Alex de Jong -

Food Sovereignty in Mexico & The Organizing Power of Women

— Ann Ferguson -

The New Sexual Radicalism

— Peter Drucker -

Making Sense of This Economic Crisis

— Ismael Hossein-zadeh - California Crisis Hits, Fightback Erupts

-

Public Education in California--What's After March 4?

— Adam Dylan Hefty -

Teachers, Parents, Community Together

— interview with Joshua Pechthalt -

Republic of Dunces

— Gray Brechin -

Undisputed Success

— Claudette Begin - Reviews

-

Myths of the Exile and Return

— David Finkel -

Terror As It Was and Is

— Aparna Sundar -

Philippines: Resisting Gobble-ization

— Michael Viola -

Sacred Roots of A People's Music

— Kim D. Hunter -

Discography to Sacred Roots of A People's Music

— compiled by Kim D. Hunter - Dialogue

-

On the Legacy of Che Guevara

— Charlie Post -

An Answer to Charlie Post

— Michael Löwy -

Reply to A Reviewer

— James D. Young -

Response

— Paul Buhle

David Finkel

The Invention of the Jewish People

By Shlomo Sand

Verso, 2009, translation by Yael Lotan, 313 pages + index.

$16.95 paperback.

SO WHERE DID “the Jewish people” come from anyway? Was there an Exodus from Egypt, an Empire of David and Solomon, an Exile ending in a triumphant Return to Zion? Does any of it matter and if so, why?

These events, whether real or fictional, are hard-wired in the culture and imagination of Western civilization, even more indelibly than the epic deeds of Harry Potter will be forever implanted in the minds of my kids’ generation. According to Shlomo Sand, however, the image of the Jewish people as a corporate body, wandering in exile from its ancient homeland since Roman times, is a mythology “rooted in the dialectic of Christian-Jewish hatred” which ultimately “took on an outright metaphysical connotation within Jewish traditions” (Sand, The Invention of the Jewish People, 134-5. All quotes are from this book except where noted).

But this runs somewhat ahead of our story. As a preface to engaging with Sand’s fascinating text and with the controversies it has inevitably generated, let’s imagine for a moment that the arguments over the rights to the lands of Palestine/Israel were conducted on a rational modernist basis — that is, by relying on the notions of basic rights of human beings that have arisen since the Enlightenment, not on myths that God chooses to favor some people and nations over others.

Admittedly, this is itself an irrational assumption: Competing nationalisms, as Sand explains if we didn’t know already, do not generally debate or behave in such fashion, least of all in the battle over Palestine — with its centuries of entanglement with colonialism, imperialism and religion.

But through what’s known as a “thought experiment,” the hypothetical assumption of modernist rationality quickly shows that the question of the Jewish people’s ancient origins, however intellectually intriguing, should make no political difference at all. To show why, we simply need to put the core of the Zionist and Palestinian arguments side by side.

The Zionist case goes like this: “The Jews, oppressed and discriminated against for centuries — and especially so in the rapidly deteriorating conditions of Eastern Europe — sought freedom and self-determination in the land of their ancestral origins.”

The Palestinian case: “The Palestinian people, living for centuries in their homeland and participating in the general anti-colonial awakening of the Arab people, had nothing to do with the persecution of the Jews in Europe or elsewhere and did not deserve to be robbed and exiled because of it.”

Next, consider two contrasting extreme-case scenarios. First, imagine that it could be conclusively proven that modern Jews of Europe, and for that matter North Africa and the Arab world too, have no ancestral connection at all to the people of ancient Israel but arose entirely elsewhere. But if the phrase “the land of their ancestral origins” in the statement of the Zionist case is simply changed to “the land where their religious culture began,” the logical validity of that appeal remains unchanged — whether you think the Zionist case itself is justified fully, partially, very little or not at all.

Alternatively, let’s make the even more extreme assumption that the global body of today’s Jews can indeed be traced straight back to ancient Israel. This does not damage in the slightest the Palestinian claim that they didn’t perpetrate the oppression of Jews, let alone the Nazi genocide, nor deserve to lose their homeland over it. Nor should their rights be affected by whether, as many scholars argue and indeed as early Zionists thought, the Palestinian peasantry were themselves descendants of Jewish farmers who stayed put after the defeats of a series of increasingly hopeless anti-Roman Jewish uprisings 19 centuries ago.

The Battleground

Back in our own world, these battles over the past really do matter, to the point where the very possibility of unbiased scholarship is called in question. The Palestinian-American Columbia professor Nadia Abu-el Haj, whose award-wining book Facts on the Ground. Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-Fashioning in Israeli Society (University of Chicago Press, 2001) documented how not only the findings but the very field of Biblical Archaeology were constructed to promote Zionism’s spiritual and earthly claims, was the target of a smear campaign to deny her tenure — spearheaded by a woman living in an Israeli settlement, of all places. The outspoken “new Israeli historian” Ilan Pappe, author of The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (Oneworld Publications, 2006), now teaches in self-imposed exile in Britain.

Joel Kovel’s book Overcoming Zionism, the subject of a review and subsequent dialogue in these pages (Against the Current 131, 132 and 133), resulted not only in Bard College effectively stripping Kovel of his job as professor emeritus, but in the University of Michigan Press severing its contract as U.S. distributor for the book’s publisher Pluto Press. The leading Palestinian-American intellectual Rashid Khalidi has been widely and viciously targeted because his friendship with Barack Obama made him “dangerous.”

Needless to say, these incidents all pale next to the atrocities being perpetrated on a daily basis in “Israel’s eternal capital” Jerusalem. I’ll come back to that issue in discussing some of the intellectual assaults on Shlomo Sand’s work.

Turning to Sand himself, both his family background and experience as a soldier in the fateful 1967 war led him first to the Communist-led Israeli left and then into the radical post-’67 Matzpen (“Compass,” the fountainhead of Israel’s anti-Zionist New Left), and a period of sojourn in France which contributed to his understanding of identity formation, including his own.

Although no longer identifying with Marxism — he writes for example that “It is not necessary to believe in Gramsci’s political utopia…to appreciate his theoretical achievement in analyzing the intellectual function that characterizes the modern state” (58) — Sand upholds the best democratic values of the left and draws from the broad traditions of historical materialism.

Sand made his academic mark in the field of French intellectual history, specializing in the thought and times of Georges Sorel, and attained tenure at the University of Tel Aviv before taking up the explosive question, “When and How Was the Jewish People Invented?” — the Hebrew title of the present work.

Quite a discovery of invention it is, too. The question is pointedly posed at the outset. Rather than a wandering nation or Biblically-chronicled ancient ethnicity:

“Perhaps, despite everything we have been told, Judaism was simply an appealing religion that spread widely until the triumphant rise of its rivals, Christianity and Islam, and then, despite humiliation and persecution, succeeded in surviving into the modern age. Does the argument that Judaism has always been an important belief-culture, rather than a uniform nation-culture, detract from its dignity, as the proponents of Jewish nationalism have been proclaiming for the past 130 years?…What are the prospects for defeating this doctrine, which assumes and proclaims that Jews have distinctive biological features (in the past it was Jewish blood; today it is a Jewish gene), when so many Israeli citizens are fully persuaded of their racial homogeneity?” (21)

Nationalism, including the Jewish versions (Zionism was not the only one), is a relatively modern development associated with the spread of the capitalist market economy, general literacy and mass politics that made possible and necessary a consciousness of identity broader than the village or clan. In his chapter “Making Nations,” Sand discusses the general terrain of how and why nationalism developed, in its relatively open “liberal” citizenship-based and its narrower “organic” blood-myth-based variants, and the ways in which it has been theorized.

This is an instructive though not highly original survey, reminding us that it wasn’t only Jewish nationalism for which “intellectuals had to utilize popular or even tribal dialects, and sometimes forgotten sacred tongues, and to transform them quickly into new, modern languages. They produced the first dictionaries and wrote the novels and poems that depicted the imagined nation…painted melancholy landscapes that symbolized the nation’s soil and invented moving folktales and gigantic historical heroes, and weaved ancient folklore into a homogenous whole…producing a long national history stretching back to primeval times.” (62)

The History of History

For me, it’s the following chapter on “Mythistory” where Sand fully hits his stride. It is not so much Jewish history but rather historiography that’s decisive, in other words the history of history, the ways in which and the purposes for which that history came to be written.

After the 1st-century CE works of Flavius Josephus, the Jewish writing of Jewish history pretty well disappears for over 1700 years, until the publication of the first volume of A History of the Israelites from the Time of the Maccabees to Our Time, by the German Jewish author Isaak Markus Jost (1820). In this work, written in the context of the struggle for Jewish “emancipation” and citizenship rights in the emerging Germany:

“Jewish history began not with the conversion of Abraham, or the Tablets of the Law on Mount Sinai, but with the return of the exiles from Jerusalem [i.e. late 6th century BCE — DF]. It was only then [for Jost and his contemporaries] that historical-religious Judaism began, its culture having been forged by the experience of exile itself. The Old Testament had nurtured its birth, but it then grew into a universal property that would later inspire the birth of Christianity.” (69)

To emphasize the point: The first modern Jewish historians saw no need to posit the Bible as the reliable historical account of the birth of a people living in unbroken national-ethnic continuity to the present day. They realized that “different Jewish communities were not members of a single body. The communities differed widely from place to place in their cultures and ways of life, and were only linked by their distinctive deistic belief,” and thereby “were entitled to the same civil rights as all the other communities and cultural groups that were rushing to join the modern nation.” (70)

The Bible-as-history viewpoint, or what Sand calls “The Old Testament as Mythistory,” came a few decades later. Jost himself began adapting to it, but it’s really with the work of Heinrich Graetz that “the Old Testament came to serve as the point of departure for the first historiographical exploration into the fascinating invention of the ‘Jewish nation,’ an invention that would become increasingly important in the second half of the nineteenth century.” (71)

In Sands’ rendering, the transformation of Jewish historiography is a dramatic one that both mirrors and responds to the rise of romantic “organic” nationalism, resting on myths of unchanging characteristics embedded in the “blood” of a nation’s people, which was already emerging in Europe and Germany in particular, with obvious negative implications for the acceptance of cultural or religious minorities.

How nasty the intellectual climate could get was illustrated when Graetz himself was attacked by the anti-semitic historian Heinrich von Treitschke, asserting that Graetz as a Jew of Eastern European origin was not and could never be an authentic or loyal German — for which Graetz “repaid the Berlin historian with the same toxic currency: Is not Treitschke a Slavic name?” (83)

In Graetz’s construction of a blood-and-soil-rooted Jewish nation, “it was mother earth, the ancient national territory…that bred nations. The land of Canaan, with its ‘marvelous’ flora and fauna and distinctive climate, produced the exceptional character of the Jewish nation” and serves as the setting for the Hebrew golden age counterpart to classical Greece, the Roman Republic, etc. (75)

Graetz himself was not a Zionist in a political sense, but his romantic rendering of an ancient-to-the-present Jewish national saga “filtered fairly easily into the early Jewish historiography pursued in Eastern Europe” (95) by Simon Dubnow and ultimately into the works of the early Zionist historians and then the Israeli establishment. Along the way, this school of national history had to confront the science of Biblical Criticism — which proved that the text was not a unified document but a complex, layered one — but the Bible narrative’s imprint on the popular imagination was decisive.

An important factor that Sand doesn’t explore here is that this reading of the Bible as an account of Israel’s exile, and its coming return to the land, dovetailed with the ideology of an emerging Protestant fundamentalism, which may not be directly relevant in contemporary Israel but is a powerful political and cultural force in the United States.

The Real History

Sand proceeds to discuss the version of Jewish history that is passed along from generation to generation, the sequence of tragic dispersions of the people from its homeland. There is, of course, the scattering of the Ten Lost Tribes following the Assyrian destruction of the Israelite kingdom. There’s the exile after the Babylonian conquest and destruction of the first Temple, with the miraculous return after 70 years.

Finally comes the most traumatic expulsion of all, the mass exile of the Jews after the Romans crushed their struggle and destroyed the Second Temple.

The problem is that this is almost all rubbish. There never were Ten Lost Tribes: The numbers of people, mostly the wealthier Israelite layers, taken into slavery by the Assyrian conquest (722 BCE) may have been in the thousands or possibly tens of thousands, but most of the agrarian population stayed and the city dwellers moved south. The Babylonian exile (586 BCE) involved the royalty, priestly elites and scribes, some of whom never did return but became the founders of the Jewish communities of Persia (Iran) and Iraq that were still thriving in the middle of the 20th century.

As for the return from Babylon, the romantic school of Jewish historians produced apologies and justifications for one of most cynical acts recorded in the Bible, when the returning priesthood compelled the men of Judea to divorce their supposedly “foreign” wives to preserve the purity of “a nation of priests and holy people.” (Ezra, chapter 10. Ilan Halevy, in his A History of the Jews, quotes the author of the Nazis’ anti-Jewish Nuremburg Laws to the effect that his model was the Codes of Ezra and Nehemiah.)

Regarding the Roman period, there was certainly death, repression and destruction — undoubtedly accelerating the economic migration that was already underway — but no mass expulsion whatever.

By the 1st-century CE there were several million Jews or “near-Jews” around the Mediterranean — by some estimates as much as 10% of the Roman Empire, though this is probably high — way more than could have arisen from natural increase and emigration of the Judean population.

There were various reasons for this. The short-lived Hasmonean kingdom — which began with the anti-Greek uprising of the Maccabees, the fundamentalist Jewish Taliban of their day, but rapidly became Hellenized in its own militarist fashion — undertook mass forced conversions in the territories it controlled. More broadly, the Jewish religion of the late first millennium BCE had taken on the character of a personal salvation doctrine, which proved to be an attractive alternative until it was supplanted by Christianity.

Already, in other words, the Jewish world was no longer that of a small people from the Biblical homeland. The wave of conversion would spread also into what is now Yemen, Syria and, as the linguist Paul Wexler of Tel Aviv University has argued, north and east to the Slavic lands and westward to North Africa — and even beyond.

Wexler’s first book, The Ashkenazi Jews: A Slavo-Turkic People in Search of a Jewish Identity, published by Slavica Press in 1993, argued provocatively that the grammatic structure of Yiddish indicates a Slavic rather than Germanic origin for the popular language of Eastern European Jewry. This remains a minority view among linguistic scholars. His subsequent work on the language and Berber origins of North Africa’s Jews has been more respectfully received (perhaps because it’s less threatening to the received historical orthodoxy?).

Sand instructively surveys a chunk of this history, but it’s not an original discovery. Rather, what’s remarkable is how deeply and how long the real history came to be submerged, how “(f)orgetting the forced Judaization and the great voluntary proselytization was essential for the preservation of a linear timeline, along which, back and forth, from past to present and back again, moved a unique nation — wandering, isolated, and, of course, quite imaginary.” (189)

There was, of course, movement — Jews did migrate, and it’s well-known that the connections between distant communities worked to their advantage in the development of medieval commerce and then of finance. But as to the myth of a nation wandering in exile, punished either for refusing to accept Jesus Christ or its failure to obey the laws of God’s covenant, Sand concludes:

“Although most of the professional historians knew there had never been a forcible uprooting of the Jewish people, they permitted the Christian myth that had been taken up by Jewish tradition to be paraded freely in the public and educational venues of the national memory [to] provide moral legitimacy to the settlement of the ‘exiled nation’ in a country inhabited by others.” (188)

Problematic Hypotheses

It seems to me that Sand may weaken his case by relying much more heavily than necessary on two theories in particular. One is known as the “Minimalist hypothesis,” associated with the American scholar Thomas L. Thompson among others, according to which the entire corpus of the Hebrew Bible was a masterful literary invention produced following the exile and return from Babylon of the Judean elites.

Sand favors this interpretation over that of the “Tel Aviv school,” which is particularly well-expressed for lay readers in two books by the Israeli archaeologist Israel Finkelstein along with Neal Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed and the newly published David and Solomon.

In the latter reading, the “first draft” of the sacred text, notably the main body of Deuteronomy purporting to be the farewell address and testament of Moses to the Israelites, was written and “discovered” by priests in the reign of the Judean king Josiah (ca. 620 BCE), for the political purpose of centralizing the sacrificial rites and political power in the Yahwist temple in Jerusalem.

It is accepted essentially all around, except of course by Bible literalists, that the texts now known as the Torah and the Deuteronomic History, i.e. Genesis through II Kings, were put in final form (“redacted” is the fancy term) after the priests and scribes returned from Babylon and set up their theocracy — the first historic “Jewish state” if you will — under the protection of the Persian empire. But controversy remains over whether earlier versions of the text existed, and their authorship and dates.

It’s clear under either interpretation that, for example, the glorious kingdom of David and Solomon could not have been more than a very modest enterprise indeed, nothing remotely resembling the fabulous United Kingdom depicted in the text, and that the real action and economic dynamism lay in the northern kingdom that is repeatedly denounced in the text for its ungodly wickedness.

As for the Exodus and conquest of Canaan, not only could these fantastic events not possibly have occurred as written during a time when Egypt actually controlled the entire region, but the Biblical text itself states that Josiah’s Passover celebration of this purported liberation was a late 7th century BCE proclamation: “Now the Passover sacrifice had not been offered in this manner in the days of the chieftans [“judges”] who ruled Israel, or during the days of the kings of Israel and the kings of Judah.” (II Kings 23:22)

Without going through lots of detail, however, it doesn’t make sense to me that the Hebrew Bible would have been written all at once as a very-late invention of an entirely imagined past. The main problem is that the text itself is so full of inconsistencies, so many different and competing names and stories of God (sometimes clumsily amalgamated to make it appear to be only one), and so many very old stories that would not have been invented by a 5th-century BCE Yahwist-monotheist priesthood.

These include the bizarre story of God attempting to kill Moses (Exodus 4:24-26), or of Moses’ magic snake constructed at God’s personal command (Exodus 4:2-4 and Numbers 21:8). These old stories are about a highly anthropomorphic deity who wanders around the earth, much unlike the more abstract, universal and distant one that the priests ultimately posited.

The Exodus legend itself must have been an old story, since well before Josiah’s time, the major prophets Isaiah, Amos and Hosea for example repeatedly refer to it — and to claim that all this literature, too, was a much later production from whole cloth seems really a stretch in view of many specific references these “Yahweh only” prophets make to detailed events of their own times.

Sand’s other problematic move is a heavy emphasis on the medieval Khazar kingdom, whose rulers and at least part of the population (how much is not completely clear) were converts to Judaism, and which at its high point “ruled over a vast landmass, stretching from Kiev in the northwest to the Crimean Peninsula in the south, and from the upper Volga to present-day Georgia” (214), as the main source of modern European Jewry.

The existence of this Jewish or at least Jewish-ruled kingdom is an established historical fact. Sand clearly exaggerates the extent to which its existence was supposedly buried by the Jewish establishment’s effort to promote the myth of ancient Israelite roots — I remember learning bits of the Khazar story in temple Sunday School, and it wasn’t from Arthur Koestler’s recounting in The Thirteenth Tribe.

Again the details of how much of today’s European Jews may be of Khazar origins are fascinating, but to overemphasize the claim seems to me to weaken the critical issue — the fact of the multiple and complex origins of the diverse communities that would become known, through ideological construction and in the course of historical trauma and catastrophe, as “the Jewish people.”

The Controversy

It is no surprise that The Invention of the Jewish People has generated intense controversy. Professor Israel Bartal of Hebrew University, a prominent go-to guy when the Israeli intellectual establishment needs an authoritative refutation of out-of-bounds criticism, wrote a scathing review of the Hebrew edition of Sands’ book in the liberal Haaretz book review supplement (July 2008). Bartal disputes little of Sands’ history but focuses on his historiography:

“My response to Sand’s arguments is that no historian of the Jewish national movement has ever really believed that the origins of the Jews are ethnically and biologically ‘pure.’ Sand applies marginal positions to the entire body of Jewish historiography and, in doing so, denies the existence of the central positions in Jewish historical scholarship.

“No ‘nationalist’ Jewish historian has ever tried to conceal the well-known fact that conversions to Judaism had a major impact on Jewish history and in the early Middle Ages. Although the myth of an exile from the Jewish homeland (Palestine) does exist in popular Israeli culture, it is negligible in serious Jewish historical discussions. Important groups in the Jewish national movement expressed reservations regarding this myth or denied it completely…[the notion of] a deliberate program designed to make Israelis forget the true biological origins of the Jews of Poland and Russia or a directive for the promotion of the story of the Jews’ exile from their homeland is pure fantasy.” (“Inventing an Invention,” www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/999386.html)

But doesn’t all this precisely prove Sand’s point? The professional intellectuals, especially when they write for their journals or for the Israeli equivalent of, say, the New York Review of Books or the Times Literary Supplement, have no need for crude myths. Yet this does not prevent every Israeli government, right, center or “left,” through which many of these same intellectuals may rotate as ministers, advisors or spokespersons, from justifying land grabs, settlements and demolition of Palestinian homes all over “Greater Jerusalem” under the banner of “the eternal capital of the Jewish people.”

The events follow in endless succession. Jerusalem mayor Nir Barkat, a “secular rightist,” will tear down the Al Bustan Arab neighborhood near the Old City to create a tourist and upscale development to be called Gan HaMelech (The King’s Garden), “a place where visitors can contemplate the kings of Judea [along with] small hotels, lovely restaurants” and no Palestinians spoiling the scene. (“Jerusalem Housing Offer Has Palestinians Crying Foul,” New York Times, February 26, 2010: A1-3).

In West Jerusalem, what remains of the centuries-old historic Mamilla Muslim cemetery will be cleared away, to make room for — what? A parking lot? A hotel complex? No, if you can believe it, for a three-acre, $250 million “museum of tolerance” to be put up by the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

The Netanyahu government received U.S. vice-president Joseph Biden’s visit to “re-start peace talks” with the announcement of 1600 new housing units for an Orthodox Jews-only settlement in East Jerusalem. Behind the usual empty blather about the timing being “a blunder and diplomatic embarrassment,” the settlers and the Israeli political apparatus are simply laughing at Biden — and granted, a sad joke he is at that.

As I’m writing this review, Netanyahu himself has responded to Hillary Clinton’s speech to the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), where she explained that Israel’s settlement rampage undermines U.S. strategic policy in the whole region. Netanyahu’s retort: “The Jewish people were building Jerusalem three thousand years ago, and we’re building Jerusalem today.” Needless to say, the hall exploded in rapturous ovation.

When masses of people are inhaling this toxic Kool-Aid, it hardly matters whether the scholars, when they talk to each other, really believe — as they certainly did while gathering “in the regular Bible circle that in the 1950s met at the house of the Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion [who] genuinely identified with Moses and Joshua” — that the Bible was real national history.

For Ben-Gurion, “the holy book could be made into a secular national text, serve as a central repository of ancient collective imagery, help forge…a unified people, and tie the younger generation to the land.” (107, 108) And the myth persists, even as the Israeli state incorporates “Greater Jerusalem” and an ever-expanding “Metropolitan Jerusalem” that now occupies close to half the West Bank.

Nor does it matter whether the intellectual sophisticates really think that the various patriarchal and matriarchal “tombs” in Israeli-occupied Hebron, Bethlehem and Nablus, which are going behind barbed wire as sacred sites for privileged Jewish settler and tourist access, hold the actual ancestors of the nation, rather than being much later creations or perhaps, in some cases, the shrines of old Canaanite deities.

On one level the present-day, really existing Israeli society no longer needs “the invention of the Jewish people.” But for purposes of maintaining the Occupation, for the expanded ethnic cleansing/urban renewal of Jerusalem and above all for warding off the demand for Israel, like modern “advanced” states, to become a state of its citizens, the invention requires continual renewal.

Critique and the Future

Where does the success of this book and the resulting controversy leave us? An enthusiastic reviewer, John Rose writes: “I’ll risk a prediction. Shlomo Sand’s book, already a best seller in Israel and France, will accelerate the disintegration of the Zionist enterprise.” (“Jewish intellectuals and Palestinian liberation,” International Socialism 125, Winter 2010, 183)

I would like to believe this, but I’m afraid it is greatly overoptimistic in the present conjuncture at least. Critique of the theory and practice of building “the Jewish state” is no longer in short supply. There was a time when dissident scholarship arising from Jewish Israeli and/or ex-Zionist voices was relatively rare and easily shoved to the margins — think of the pioneering work of the Marxist Nathan Weinstock, or Hannah Arendt, or Israel Shahak. Today, since the intellectual and activist Big Bang of Matzpen and its fragments, and following the emergence of the “new historians” within Israeli society who have told the full story of conquest and ethnic cleansing, the critical literature is a flood.

Shlomo Sand’s work accompanies that of Gabriel Piterberg’s brilliant The Returns of Zionism. Myth, Politics and Scholarship in Israel (Verso, 2008), Zeev Sternhell’s The Founding Myths of Israel (Princeton University Press, 2001), the writings of the late Baruch Kimmerling and Tanya Reinhart, Michael Warschawski’s Toward an Open Tomb. The Crisis of Israeli Society and On the Border, voluminous studies of the Occupation and the systematic degradation of Israel’s Palestinian minority, the scathing journalism of Amira Hass and Gideon Levy in Haaretz, and so much more.

Within part of the pro-Palestinian movement, there seems to be a kind of inverted-Zionist view that Israeli society itself is so built on sand that the demolition of historical falsehoods alone will bring on its demise. Like most of Israel’s own harshest internal critics who know their society well, Sand himself does not share such a view.

The critical analysis indeed proliferates by the year, and Sand’s book makes a signal contribution to it. There is also a powerful growing critique in progressive Christian circles of the poison spread by Christian Zionism. Yet on the ground the U.S.-protected Israeli state machinery continues to trample everything in its path, even setting in motion the process of its self-destruction as its own critics have warned. In the end, the progressive and necessary “disintegration of the Zionist enterprise” depends crucially on the attrition of Israel’s status as a key imperialist asset for the United States, and secondarily for Europe, to police the Middle East.

This requires among other things the success of the growing movement to treat the Israeli state with the same moral and ethical revulsion with which decent elements in the international community treated apartheid in South Africa. In this struggle, the body of critical analysis certainly makes an important — but secondary — contribution. The declining power of the patron superpower is the most critical factor, and Israel’s own behavior certainly plays a major part.

But it will be further down the road, as the internal crisis of Israeli society and the international isolation of the Israeli state deepen, that the real power of Shlomo Sand’s narrative and his concluding challenge may be heard:

“To what extent is Jewish Israeli society willing to discard the deeply embedded image of the “chosen people,” and to cease isolating itself in the name of a fanciful history or dubious biology and excluding the “other” from its midst?… If the nation’s history was mainly a dream, why not begin to dream its future afresh, before it becomes a nightmare?” (313)

In short, can Israel/Palestine and its two peoples be liberated from Zionism and its sustaining mythologies? The possibility exists, however remote it seems at present, that an Israeli society in crisis might confront its real situation and respond rationally, in the sense I tried to define at the beginning. That would entail a radical reconstruction of Israel’s institutions on the basis of equal rights, and a reimagining of its origins and future as profound as the changes in the United States produced by the epic Black Liberation Movement and the other struggles it inspired. For Sand, this dream is worth striving to achieve.

ATC 146, May-June 2010

Sands’ book is one of many which I don’t expect to read but whose reviews I consume compulsively. I think this thoughtful review strikes a good balance. I, too, was put off by his embrace of the Khazar hypothesis. And, in the end, I’m unconvinced that the whole idea that the book has much political importance for the reason the reviewer explained.

The Zionists stress Jewish connection to the land in ethno-nationalist terms but play upon the religious imagery for extra emotional oomph. And the fact is, from the religious perspective, Judaism’s territorial dimension is undeniable.

But returning to my earlier point, none of this matters in modern political terms. About a million Palestinian Arabs were forcibly displaced from their land and the State of Israel has staked its existence on constantly humiliating and intimidating and, when that fails, physically smashing its Arab neighbors. The books thesis neither strengthens nor weakens the Zionist claim on the land or the anti-Zionist case against this claim.

The following letter to the editors was sent by George Fish in Indianapolis.

David Finkel’s fine review-essay, “Myths of the Exile and Return,” in Against the Current 146 (May/June 2010), elevates understanding of the issues involved in the continued Israeli subjugation of the Palestinian people through perpetuation of the Zionist myth of the return of an exiled people to their ancestral homeland. But his essay, while a most welcome clarification, needs to be expanded on through further clarifications, which this letter will attempt to provide.

While the Zionist myth of an ancestral “Jewish people” is well dissected and dismissed by Finkel’s essay, Finkel errs by not giving enough attention to the concrete existence of a “Jewish people” in Europe that was subjected to two millennia of Christian anti-Semitism and persecution that culminated in the Nazi Holocaust. This was clearly an historic “Jewish people” that was seen as constituting a “Jewish problem” in Europe, and of course, this European Jewish people was the subject of the specifically European campaign to exterminate it that culminated in the murder of 6 million Jews during World War II, an extermination subsequently followed by the European refusal to concretely re-settle those specifically European Jews who had survived.

Europe’s blind refusal to take responsibility for what happened during the Holocaust was, of course, a great boon to the Zionists; they could now clamor that a specifically Jewish state, Israel, was necessary to protect Jews from a future Holocaust. Thus were large numbers of Jewish settlers of specifically European origin foisted upon the Palestinian Arabs who lived in Palestine, which was now designated as the specifically Jewish State of Israel. These were, of course, Jewish refugees created, first, by the Holocaust, and, then, by the European refusal to own up to this specifically European atrocity.

These Jews were made refugees in their actual homelands by a specifically European desire to be rid of this “problematic” people, who were then granted a sop at the expense of another people who also didn’t count. This is a necessary expansion of Finkel’s essay: pointing out the specifically European roots of the subsequent Zionist claim that Judaism = Zionism = the necessity of the specifically Jewish State of Israel born of necessity by anti-Semitism and Holocaust memories, and essential to the very physical survival of Jews themselves.

What complicates this matter for us in the early 21st Century is that another myth of an exiled people has also been perpetuated: the myth of an “Arab people” that was also dispossessed, and the identity of this “Arab people” as, further, an “Islamic people” who must confront an alien “Jewish people” in the name of Islam, a confrontation necessitated not only by the just claims of the dispossessed Palestinians, but also by adherence to the Will of Allah. With the defeat of secular Arab nationalism and secular pan-Arabism there has arisen an Islamic pan-Arabism that is just as totalizing as Zionism—and just as pernicious.

The rise of this Islamic pan-Arabism in the wake of the failure of secularist pan-Arabism is the subject of two insightful articles that appear in the current issue of the scholarly journal Critical Review (vol. 22, no. 1, 2010). This Islamic pan-Arabism makes three claims: the “natural” dominance of the Arab world over the whole of worldwide Islam due to the Arabic origins of Islam. This claim is advanced even though the majority of the world’s Muslims are not Arabs (“Arab” properly means the people of the Arabian Peninsula, and those descended from them. Iranians and Indonesians, who inhabit the country with the world’s largest Muslim population, are not Arabs, although most of them are Muslims); the appellation of “Arab” to all who speak Arabic (which is itself a language comprised of many mutually unintelligible dialects); and the further justification of specifically Arab dominance as the “natural” fruit from the “Islamic golden age” that arose in Medieval times when the specifically Arab people successfully led wars of imperial conquest that not only spread Islam beyond the Arabian Peninsula into the Middle East, Africa, the Byzantine Empire and parts of Europe; but also foisted Arab rulers on these non-Arab peoples; forcibly converted their populations to Islam; and also, in certain territories conquered, foisted Arabic on them over their native languages.

Thus another (equally specious) equation: Islam = Arabism = “natural” Arab dominance over both non-Arab Muslims and over non-Islamic peoples living in Islamic countries. Relating this to the Israeli-Palestinian struggle, Islamic pan-Arabism supports the claims of the Palestinians not only in the name of Palestinian self-determination, but also by a broader claim of Islamic Arabic superiority over a non-Islamic “alien” people, i.e., Jews as such.

Readers of this letter should also consult Ibn Warraq’s Why I Am Not a Muslim in addition to the two articles referenced above. Warraq’s book is a treasure trove of information on Islam and the historical record of the Arab conquest, and a great dispeller of myths on Islam. One of these myths is the supposed tolerance of Jews and Christians within Islamic societies. Jews and Christians were, in fact, second-class citizens who were subject to special taxes due to their “infidel” nature.

Not only was this true historically, but the Koran itself specifically denigrates the Christian and Jewish religions as incompatible with Islam, and also specifically denigrates Jews as worse than Christians. Thus can be found in the Koran itself a specifically Islamic form of what can only be called direct anti-Semitism. Once again, I refer the reader to an easily accessible book: the Penguin Classics edition of the Koran as translated into English by N.J. Dawood. (Both Dawood’s translation and Warraq’s book are available in paperback.)

This specifically Islamic justification for anti-Semitism can be seen in Dawood’s translation (on pp. 391-396) from the Koranic chapter called “The Table,” 5:41-5:82. 5:82 bears quoting in its entirety: “You will find that the most implacable of men in their enmity to the faithful [i.e., Muslims] are the Jews and the pagans, and that the nearest in affection to them are those who say: ‘We are Christians.’ That is because there are priests and monks among them; and because they are free from pride.” It needs also to be noted that certain Islamic groups who support the Palestinians distribute those anti-Semitic “classics,” “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion” and Henry Ford’s The Eternal Jew.

This brings us now to Hamas, and Islamic Holocaust denial. Holocaust denial, as we know, is the contemporary vogue among anti-Semites, and one infamous example of it in an Islamic country was the conference called in Iran a few years ago under the aegis of Iran’s President Ahmadinejad that specifically promoted Holocaust denial, and was attended by such “luminaries” as U.S. neo-Nazi David Duke. But Holocaust denial is also specifically supported by Hamas. Matthew Rothschild’s article in the September 2, 2009 issue of the Progressive, “The Holocaust and Palestine,” which was also distributed online by the left news listserve Portside, quotes Hamas legislator Jamila al-Shanti as saying, “Talk about the Holocaust and the execution of the Jews contradicts and is against our culture, our principles, our traditions, values, heritage, and religion.”

Rothschild’s article also quotes Hamas’s spiritual leader Yunis al-Astal remonstrating against the U.N.’s plans to teach children about the Holocaust in the schools it ran in Gaza as “marketing a lie” and a “war crime.”

But Rothschild’s article also quotes the late Edward Said, certainly no supporter of the Israeli occupation, in most needed and relevant riposte. “Writing in Le Monde Diplomatique in 1998,” says Rothschild, “Said noted”:

“Whether we like it or not, the Jews are not ordinary colonialists. Yes, they suffered the Holocaust, and yes, they are the victims of anti-Semitism….But no, they cannot use those facts to continue, or initiate, the dispossession of another people that bears no responsibility for either of those prior facts….We must recognize the realities of the Holocaust not as a blank check for Israelis to abuse us, but as a sign of our humanity, our ability to understand history, our requirement that our suffering be mutually acknowledged….The real issue is intellectual truth and the need to combat any sort of apartheid and racial discrimination, no matter who does it. There is now a creeping, nasty wave of anti-Semitism and hypocritical righteousness insinuating itself into our political thought and rhetoric. One thing must be clear in my firm opinion: we are not fighting the injustices of Zionism in order to replace them with an invidious nationalism (religious or civil) that decrees that Arabs in Palestine are more equal than others. The history of the modern Arab world -— with all its political failures, its human rights abuses, its stunning military incompetencies, its decreasing production, the fact that alone of all modern peoples we have receded in democratic and technological and scientific development -— is disfigured by a whole series outmoded and discredited ideas, of which the notion that the Jews never suffered and that [the] Holocaust is an obfuscatory confection created by the Elders of Zion is one that is acquiring too much, far too much currency.”

George Fish

Indianapolis, IN