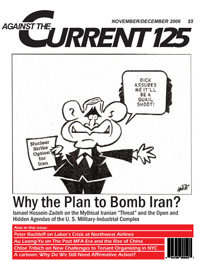

Against the Current, No. 125, November/December 2006

-

The End of the Regime?

— The Editors -

Israel, Lebanon and Torture

— an interview with Marty Rosenbluth -

The Profits of War: Planning to Bomb Iran

— Ismael Hossein-zadeh -

Racist Undercurrents in the "War on Terror"

— Malik Miah -

War and the Culture of Violence

— Dianne Feeley -

Creating A Giant Ghetto in Gaza

— Uri Avnery -

George Bush's Unending War and Israel

— Michael Warschawski -

The Post MFA Era and the Rise of China, Part 1

— Au Loong-Yu -

Dual Power or Populist Theater? Mexico's Two Governments

— Dan La Botz -

New Challenges to Tenant Organizing in New York City

— Chloe Tribich -

The Case of Northwest Airlines: Workers' Rights & Wrongs

— Peter Rachleff - Reviews

-

James Green's Death in the Haymarket

— Patrick M. Quinn -

Eliizabeth Kolbert's Field Notes from a Catastrophe

— John McGough -

David Roediger's Working Toward Whiteness

— René Francisco Poitevin -

Paul Buhle's Tim Hector

— Sara Abraham -

Latin America to Iraq: Greg Grandin's Empire's Workshop

— Samuel Farber - In Memoriam

-

Caroline Lund-Sheppard, Sept. 24, 1944-Oct. 14, 2006: A Life Fully Lived

— Jennifer Biddle -

Remembering Dorothy Healey: An Activist with Vision

— Robbie Lieberman

Dianne Feeley

LAST YEAR I had the opportunity to see “Winter Soldier,” a rarely shown 1971 documentary based on the testimony of over 100 soldiers recently back from Vietnam. It was filmed during a three-day hearing on war crimes that Vietnam Vets against the War organized in Detroit. Young soldiers spoke about atrocities they had committed in the name of freedom and democracy: throwing suspects out of planes, torching villages, raping women, killing civilians. Of course the Nixon administration attempted to discredit the soldiers and their stories.

For me, one scene stands out vividly: a soldier talking about what he had done while his wife and young child were in the background. I kept thinking: How had he been able to overcome his guilt and develop a loving relationship with his family? Or had he?

The My Lai massacre of 347 civilians occurred in 1968. Seymour Hersh broke the story in a New Yorker article the following year. During this same time period General William Westmoreland, commander of the U.S. forces in Vietnam, set up a task force to monitor war crimes allegations. Amounting to 9,000 pages, the files were declassified twenty years later and placed in the National Archives.

Documentation includes witness statements and reports by military officers substantiating 320 atrocities, and reporting another 500 allegations. At the time government spokespeople maintained that war crimes were committed by a few rogue units, but the testimony implicates just about every military unit in Vietnam. The files detail:

* Seven massacres in which at least 137 civilians died.

* Seventy-eight other attacks on civilians, of whom at least 57 were murdered, 56 wounded and 15 sexually assaulted.

* One hundred and forty-one cases in which U.S. soldiers tortured civilian detainees or prisoners of war, using fists, sticks, bats, water or electric shock.

* Only 57 soldiers were court-martialed, resulting in 23 convictions. A military intelligence interrogator received the stiffest sentence, 20 years. He was convicted of committing indecent acts on a 13-year-old girl while she was being interrogated in a hut. He served a total of seven months.

Of course these cases did not constitute a comprehensive review. Only those reported to the military were investigated. And even in the 203 cases where the evidence reviewed by the military was strong enough to warrant charges, most resulted in no action being taken.

This year reporters from the New York Times examined about a third of the documents before the government snatched them away, saying that they contained “personal information” and therefore were exempt from the Freedom of Information Act.

Just as corporations don’t want to cost out the environmental damage that results from their manufacturing processing, the government doesn’t figure in the real cost of warfare. In fact, whether the woman who is sexually assaulted is a civilian, a military woman, or the soldier’s wife or girlfriend, the perpetrator can almost always count on the military unit to remain silent.

Even when there is an investigation, the military prefers to maintain discretion by handling the case administratively. This results in a letter of reprimand, or dropping the charges. Even in the face of laws against sexual assault, the system finds a way to cover up or minimize the crime.

Violence becomes the method with which governments and individuals in positions of power (relative to the “other”) impose their will. Violence isn’t something that only happens out there, to the “others” while “we” come back to our safe homes.

War, Colonialism and Torture

Training for war is learning to dominate the enemy. One is taught to destroy “targets” from afar or “control” a civilian population closer at hand. But in either case enemies — and anyone seen to be helping them — are to be tamed or eliminated. The enemy must quickly learn that they are powerless in the face of a superior force.

This dynamic provides the soldier with a powerful sense that whatever he/she does is necessary and good. In dehumanizing others, the aggressor perceives the enemy as less than human, and therefore “deserving” of mistreatment. Just as the battered spouse learns she was abused “for her own good” and therefore abuse is a sign of “love,” so too the enemy is supposed to give up any possibility of resistance.

This, in fact, is the story of America. The colonists came and subdued the Native Peoples, thus “proving” that they were the chosen ones. The Native Americans, once defeated, were herded onto reservations. In many cases, their children were forced to go to boarding schools where they were not allowed to speak their language or dress in their fashion. Torn from their families and culture, the children were often physically and sexually abused by those who were in charge of them. Of course, this brutality was carried out as an exercise in western civilization.

Today we hear, as a justification for the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, that the people whose government was overthrown need Washington’s “help.” If U.S. troops pulled out, the story line goes, chaos would ensue. Policing the world is hard work and, by definition, only the good and brave apply.

In the war against terrorism, President George W. Bush has set the stage for a permanent engagement in which the forces of democracy and freedom square off against the forces of “Islamic fascism.”

After 9/11 the administration announced, “You are with us or you are with the terrorists.” In this war, although Bush has reassured the world that Americans don’t torture, torture is permitted.

How is this seeming contradiction resolved? A March 2003 memo on torture crafted by John Yoo, White House lawyer at the time, provided the escape hatch: Torture isn’t torture when it doesn’t permanently injure or murder. Under this definition it’s pretty clear that threatening or humiliating prisoners isn’t torture.

According to administration spokespeople, furthermore, torture isn’t torture when extracting information from a terrorist could prevent a catastrophe. The Christian Science Monitor, reporting on Bush’s acknowledgement of secret CIA prisons and methods of interrogations, explained that was how the government received information that Jose Padilla was plotting to detonate a bomb:

“We knew that [Zayn Abu] Zubaydah had more information that could save innocent lives, but he stopped talking,” the president said in a speech on Sept. 6. “So the CIA used an alternative set of procedures.”

The CSM reporter, Warren Richey, noted that Bush insisted that torture was not used, but declined to identify specific practices. However, Richey pointed out that Padilla’s defense lawyers discovered that Binyam Mohammed, a source for the warrant against Padilla, was being held in Pakistan where U.S. agents wanted him to provide incriminating information about Padilla.

Pakistani agents hung Mohammed on a wall with a leather strap around his wrists for a week. Later he was beaten with a leather strap and questioned while a loaded gun was pressed into his chest.

Unhappy with his “level of cooperation,” U.S. agents had Mohammed sent to Morocco where interrogators used a razor blade to make 20-30 small cuts on his genitals. Today he is in Guantanamo. Aside from the horrible “procedures” used, one might wonder about the quality of the information. (“’Alternative’ CIA Tactics Complicate Padilla Case,” CSM, 9/15/06)

The Facts of War

Of course we don’t know the full extent of current atrocities in Iraq, Afghanistan and in the prisons where “suspected terrorists” are being interrogated. But we do know abuse is built into a situation where soldiers are expected to force the population to submit to their own powerlessness. Here are a half dozen reports of abuse:

* In November 2005 a squad of U.S. Marines killed 24 civilians at Haditha after a roadside bomb killed one of their fellow Marines. The sergeant who led the squad claims they followed the “military rules of engagement” and did not intentionally target civilians. On the other hand, neighbors recounted that some of the executed begged for their lives before being shot, refuting the military’s version.

* 14-year old girl, Abeer Qassim Hamza al- Janabi. One of the soldiers had been harassing her so much that her mother was planning to have her stay with another relative. The four raped and murdered her, torching her body in an attempt to destroy the evidence, and then killed her parents and younger sister.

* Six Marines and a navy medic have been charged with assaulting civilians in order to extract intelligence. Three kidnapped and killed an Iraqi man, placing an AK-47 rifle and a shovel next to his body to make it look as if he was an insurgent planting a roadside bomb.

* In May 2006, on an island in Tharthar Lake, four soldiers killed three Iraqi detainees bound with plastic handcuffs. At a military hearing in August, investigators suggested that the brigade’s commanders created an “atmosphere of excessive violence by encouraging ‘kill counts.’” (LA Times, 8/3/06)

* Also in May, two women on their way to a hospital in Samarra were shot in the back of the head by U.S. snipers, who then attempted to hide the evidence. One of the women was pregnant.

* According to the military’s investigation of Abu Ghraib, there were 44 accounts of sodomizing detainees, stripping prisoners naked and leading them around on leashes, or attached electrical probes to their genitals.

In military training, soldiers learn they act as guardians of freedom and the American way of life. Their task is to be a “warrior” who never accepts defeat. Physically and mentally “tough,” the soldier stands ready “to engage and destroy” the country’s enemies in close combat. (Quotes from the U.S. Army’s Soldiers Creed) No wonder we get so many military personnel who act as macho men.

Soldiers, trained and equipped, are put into harm’s way. Their friends get killed, they face a rather undefined enemy, and they are plopped down into a completely different culture. Their stay has been extended beyond the standard year of duty. Many are on their second or third tour in Iraq or Afghanistan. Under these pressures it becomes relatively easy to use excessive force, realize you want something and grab it, or intimidate, humiliate or torture a prisoner.

Upon reflection, the pictures of soldiers torturing and humiliating prisoners at Abu Ghraib don’t seem as shocking. The temptations to humiliate, intimidate and murder are built into the hierarchical and powerful military machine, reinforced by the president’s aggressive rhetoric.

Training for Masculinism

As someone who defines herself as a socialist feminist, I’ve tried to think about how gendered categories work. In our society we can’t even talk about a newborn without knowing the baby’s gender! We assign nurturing tasks to women and security and protection to men. This is then reinforced in myriad ways throughout our childhood, youth and adult lives. It is this masculinist role that the military builds on, even today when 15-20% of the army is female.

In Tod Ensign’s study America’s Military Today, the chapter on “Women in the Military,” written by Linda Bird Francke, is subtitled “The Military Culture of Harassment.” Francke examines how the culture is driven by a group dynamic centered on affirmation of masculinity. Anything despicable is female. She notes “If the Freudian observation is true that the tenets of masculinity demand man’s self-measure against other men, military service offers the quintessential paradigm.”

Francke also quotes Tod Ensign, director of Citizen Soldier: “To be called ‘STRAC’ (Straight, Tough and Ready for Action) is a great compliment. That means you’re ready to jump out this window, rappel down the side of the building and kill someone with a pencil.” (136)

With this as the training, it’s easy to see how an occupying army, pumped up on the arrogance of power, commits atrocities against those perceived to be enemy. So too is the group’s willingness to remain silent or even participate in the cover up of a crime committed by one or more of its members.

Those who do confront the criminals directly, as army medic Jamie Henry did in Vietnam, are told “if I wanted to live very long, I should shut my mouth.” (“Vietnam, The War Crimes Files,” by Nick Turse and Deborah Nelson, LA Times, 8/6/06)

After the Abu Ghraib photographs many wondered how women in the military could participate in these atrocities. But this is not the first time American women have been caught on camera as participants.

Examine the pictures of lynchings and you will discover women — and children — part of the smiling crowds. The nurturing role women have been assigned has been suppressed by her group identification with the strong and powerful.

Sexual Assault within the Armed Forces

Women in the military are trained to drive out their female “softness,” although not so much that they become men and therefore compete with the “real” guys. In fact even in today’s volunteer army they are almost always assigned to support roles, not combat ones.

Given the military’s strict gender imagery, the strong male identity and the centrality of male readiness for combat, sexual assault on women in the military is a frequent occurrence. Some estimates suggest perhaps one out of every three military women faces sexual violence. But we know for sure that at least 500 sexual assaults involving U.S. forces in Iraq and Afghanistan were reported.

A 2005 Pentagon report noted a 25% increase between 2003 and 2004 in the number of reported cases in which military men had sexually assaulted military women. The escalation could not be explained by a greater number of women serving in the military, or being mobilized into combat zones, or by better reporting of crimes. For the first time, too, the report listed 425 civilian victims of assaults.

The most recent case of a woman soldier reporting sexual assault is that of Suzanne Swift. She was 19 when she was first sent to Iraq. Her squad leader pressured her into a relationship that she broke off after a few months, after which she was repeatedly harassed by him.

Lory Manning, director of the Women in the Military Project, pointed out that such a sexual liaison is not considered consensual even when the victim goes along. What made it even more difficult for Swift is while she stationed in Iraq the person in charge of her was her harasser and she failed to file a complaint.

Swift encountered two other instances of harassment. Back in Ft. Lewis she asked a sergeant in her chain of command where she should report for duty. He replied, “In my bed, naked.” When, in front of others, he sexually harassed her she filed charges. He was given a letter of admonishment and reassigned to another unit.

After eight months of being back in the United States, Swift was ordered back to Iraq for a second tour. She did not report but sought therapy for post-traumatic stress and a discharge. The army said it did not negotiate with deserters and arrested her. After an investigation, the army has charged her with being AWOL. (See <a href=”http://suzanneswift.org” target=”_blank”>http://suzanneswift.org</a> particularly “From Victim to Accused Army Deserter, Donna St. George, Washington Post, 9/19/06)

Bringing the War Home

Few studies have compared military domestic violence with the civilian world, but one study done in the 1990s suggests that it is twice the rate of the civilian population. Military records reveal that between 1997 and 2001 there were an average of more than 10,000 substantiated cases a year.

Over the last several years we have heard of returning soldiers killing their spouses or girl friends in Ft. Bragg, Ft. Hood and Ft. Lewis. During the summer of 2002 four soldiers from elite units in Ft. Bragg, North Carolina killed their wives; two then killed themselves. Three of the four had recently returned from Afghanistan.

In comparing post-traumatic stress disorders soldiers have suffered in various wars, it seems to range somewhere between 15-30% who sought medical help for their condition. Studies indicate that those with the highest symptoms were front-line soldiers — it is more traumatic to be on the front lines than in prison.

A recent Veterans Health Administration report pointed out that more than one-third of the soldiers who served in Iraq and Afghanistan sought help for post-traumatic stress, drug abuse or other mental disorders, a tenfold increase over the last 18 months.

Factors that might contribute to the higher levels of stress include roadside bombings, unpredictable daily attacks and the fact that tours of duty are spaced too close together. Soldiers are already returning to Iraq and Afghanistan for second or third tours of duty.

The soldier returning from battle has learned to live with violence. And because of that, he’s got a greater chance, over the course of his life, to turn the violence he’s learned against himself, his family or others.

But the problem is larger than post-traumatic stress. It’s really about how our society forces human beings to adopt a competitive, aggressive and stressful stance that can only lead to violence, particularly against those perceived to be weak.

The institutional, masculinist mindset gives an inordinate amount of power and self-justification to soldiers, whether in war or in recruiting others for war. An Associated Press investigation found that in 2005 more than 80 military recruiters were disciplined for sexual misconduct with women who had come to them seeking advice.

Misconduct ranged from groping to rape, but once again the military’s response was administrative, with the recruiter suffering a reduction in rank or a fine. How many more went unreported?

It’s time to say, once and for all, that this hierarchical and gendered violence is antithetical to developing the full capacities of human beings.

ATC 125, November-December 2006