Against the Current, No. 118, September/October 2005

-

On to September 24th!

— The Editors -

The NAACP's Future

— Malik Miah -

Muslims in Britain: After the London Bombs

— Liam Mac Uaid -

Solidarity with Iraqi Labor

— Traven Leyshon and Dianne Feeley -

The Message and Meaning of Groundings 2005: Walter Rodney Lives!

— Sara Abraham -

Creating A Movement for Reparations

— Andrea Ritchie -

Economic Crisis & Fundamentalism

— Susan Weissman interviews John Daly -

Kyrgyzstan After Akayev

— Susan Weissman - Attacks on the Academic Left

-

Assaulting pro-Palestinian Activism: Smear Tactics at U-M

— Nadine Naber -

Labor Studies Under Siege

— Stephanie Luce -

Racism & Conflict at Southern Illinois

— Robbie Lieberman - Celebrating the Revolutionary Centenary

-

Rehearsing for 1917: Russia's 1905 Revolution

— David Finkel -

A Hidden Story of the 1905 Russian Revolution: The Unemployed Soviet

— Nikolai Preobrazhenksii -

Rosa Luxemburg & the Mass Strike

— Lea Haro -

Lessons from the 1905 Revolution

— Hillel Ticktin - In Memoriam

-

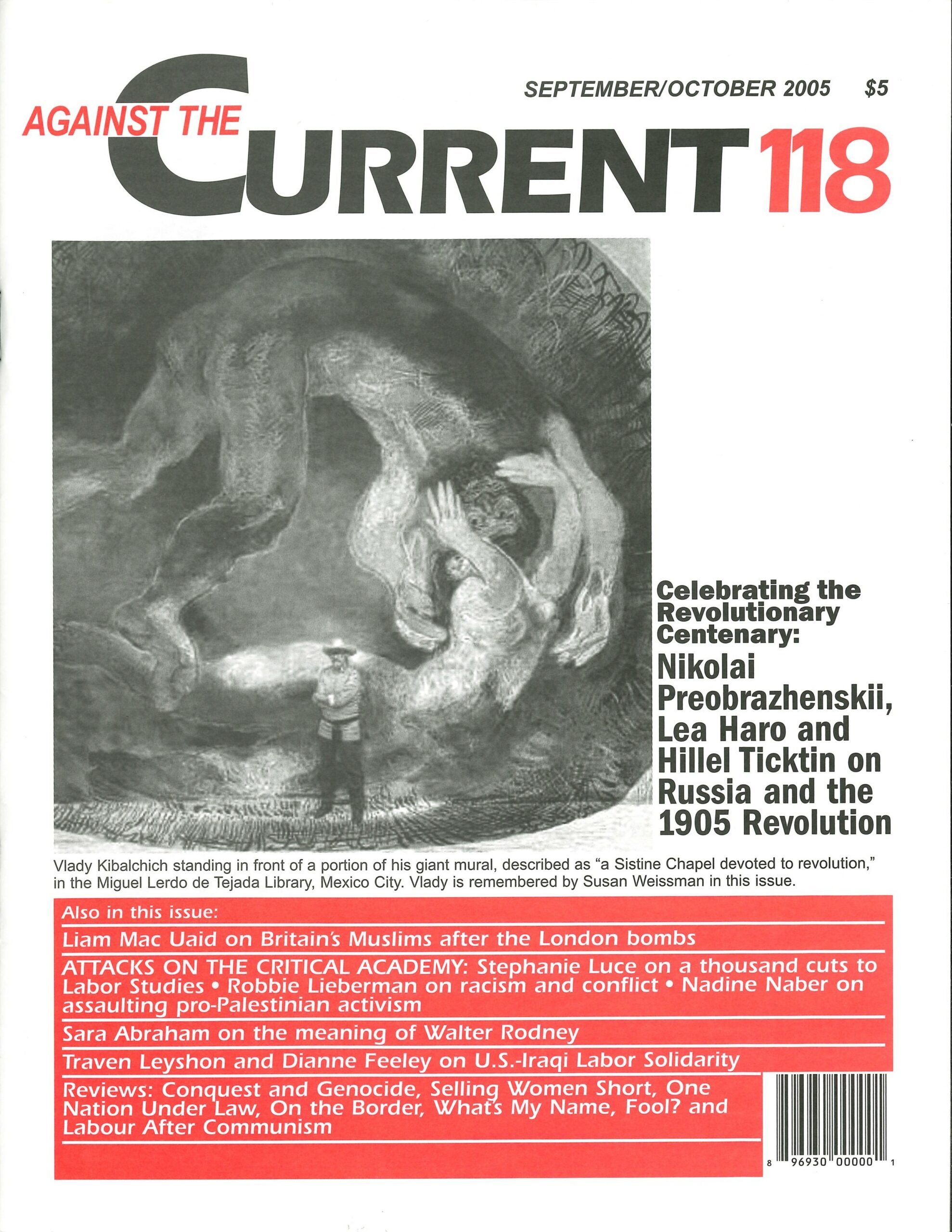

Remembering a Revolutionary Artiist: Vlady Presente!

— Suzi Weissman - Reviews

-

U.S. Law: Religious or Secular?

— Jennifer Jopp -

From the Front Lines of Native Women's Struggles

— Andrea Ritchie -

Fighting the Wal-Mart Plague

— Karen Miller -

Sports & Resistance

— Peter Ian Asen -

An Israeli Anti-Zionist Memoir: On the Border

— Larry Hochman -

Already in Hell: Labor After Communism

— George Windau

Susan Weissman interviews John Daly

[Susan Weissman, host of “Beneath the Surface” on KPFK, Pacifica radio in Los Angeles, conducted this on-air interview with John Daly in April, 2005. Many thanks to Walter Tanner for transcribing. It has been edited and abridged for publication.]

SUZI WEISSMAN: JOHN Daly is the International Correspondent for UPI, a contributing editor to Vanity Fair, and writes for Janes’ Defense publications. He speaks Turkic languages and is an adjunct scholar at the Middle East Institute in Washington, D.C.

On the UN Human Development Index, Kyrgyzstan slipped from 31st place in 1991 to 102nd place in 2003, making it one of the poorest countries in the Commonwealth of Independent States. The population then turned on the President. What can you say about this so-called “Tulip Revolution?” This time it is a flower rather than a color, as we saw with the Georgian Rose Revolution and the Ukrainian Orange Revolution.

John Daly: When you speak about Ukraine and Georgia, the uprisings occurred in the capital whereas in Kyrgyzstan, the problems began in the southern regions of the country, specifically the Fergana city of Osh. It is also largely Muslim — there is a great north-south divide in Kyrgyzstan.

According to Kyrgyzstan government statistics, two-fifths of the workers there live on 300 (Kyrgyzstani) Som a month, about $3. Approximately four-fifths of Kyrgyz families live under their officially defined poverty line. So there is an immense divide between the haves and the have-nots.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Kyrgyzstan’s industrial base imploded and many of the Russian specialists left. Now, for example, 40% of its foreign earnings come from a single gold mine — Kumtor — up in the Tien Shan mountains.

SW: Are there any hopes of improvement now that Akayev is ousted?

JD: The problem is that no one in the wings has any immediate solutions. You can break up the collective farms, for example, but if you start parceling bits of it to the people who work it, where are they going to get the loans for tractors, for seeds, and where are they going to get a guaranteed market?

What you have is nearly a decade and a half of people who have been fed a great line about democracy being better than communism, yet under communism they had a stable pattern of life, little inflation, their kids went to school, the infrastructure worked and they had jobs. Of course they had to keep their mouths shut on sensitive political issues, but democracy in Kyrgyzstan, for many people, seems to mean freedom to starve.

SW: Kyrgyzstan is right in the heart of Central Asia. It is a tiny little area that has less than five million people?

JD: Yes, and a great deal of it is mountainous. They do have some resources, for example hydro-electric power. It is very scenic and they’ve been developing their tourism infrastructure around Issyk Kul Lake. (Listed on map as Ysyk-Köl.) But how do you take a centrally planned economy largely directed to the military-industrial complex and turn people into entrepreneurs?

There are a number of mindsets which have been inherited from the Soviet Union. One is that it was a society of shortage. You really had to scramble to get things like toilet paper; there were no centralized markets so you had to go to one truck to get your onions, and somewhere else to get your bread. If you could acquire something, you maximized it, because tomorrow could well be worse, the opportunity could disappear.

Now, the Soviet experiment did leave the Kyrgyz people with a number of benefits, for example, their educational structure. But to shotgun marry the Kyrgyz economy to the global economy, there’s not really much they have to offer in the short term.

SW: You mention in one of your articles the sad fact that this is now part of the power play between two empires, much as it was in the 19th century. This time both Russian and U.S. military bases are on its territory.

JD: Yes, we have an airbase at Manas. The Russians were appalled and pressured Akayev to have one about 25 miles away, the first base built outside of the Russian Federation in 1991. But it’s not a two-way struggle, it’s a three-way struggle, because of course bordering to the east is China.

SW: You see Kyrgyzstan as an epicenter of anti-terrorist activity, with both Russian and American bases and a power vacuum that you say could well provide for an opportunity for the secretive organization, Hezb ut- Tahrir, to attempt a takeover. Is this going to be the selling point for the military buildup?

JD: Central Asia has been traumatized by Afghanistan since 1979. Washington is guilty for some of it because of course we armed the Mujahadeen. And in their war against the USSR, the people who survived the Soviet occupation were the toughest of the tough.

Furthermore, in 1985 then-Director of the CIA William Colby went to Islamabad and encouraged the patrons of the Mujahadeen, Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence, to conduct raids into the Soviet Union, into southern Uzbekistan. So what you had when the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan was a power vacuum. The country descended into civil war, which was only wound up when the Taliban took over.

When the Taliban took over, of course, it became a magnet for every wannabee Jihadi, and along with that was the revival of the Afghan opium industry. So you had this nexus develop between terrorism and drug running. Kyrgyzstan, along with other former Soviet states, joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. The anti-terrorism center for the SCO is actually in the Kyrghyz capital Bishkek.

You don’t have just the problem of Al-Qaida, but also Hezb ut-Tahrir. You’ve also have remnants of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, which based itself in southern Kyrgyzstan in 1999 and 2000, conducting raids into Uzbekistan. So you have a multi-layered terrorist pie, as it were. And the Uzbeks are in the center of it.

SW: Given the rise of this secretive organization and influence from its neighboring Muslim republics, what can you say about the adherence of the population to the kind of Islam that worries our leaders the most?

JD: The first thing to remember is the Soviet Union was officially an atheist state, and in terms of religion it was an equal- opportunity oppressor. It went after the Russian Orthodox Church, it went after the Muslim communities as well. To give you an idea of the change, in 1991, the last year of communism, there were 91 mosques in Kyrgyzstan. Now there are over 2000.

In the Soviet period, if you were Muslim, of course, one of your religious duties was to go on the pilgrimage to Mecca called the Hajj. A handful of Kyrghyz went during the Soviet period: they were all very carefully selected. Since 1991, 11,000 have gone.

But the problem is the actual level of religious knowledge. Because they had a three-generation break with tradition, the overall level of knowledge of Islam, not only in Kyrgyzstan but the rest of Central Asia, is still fairly low. With the collapse of communism, of course, evangelicals flooded the former Soviet Union, not only Christian but Muslim. By the time the government awakened to the fact that some of these had a radical agenda, to a certain extent, the worse of the damage was already done.

SW: Tell us more about the Hezb ut-Tahrir.

JD: The problem with Hezb ut-Tahrir is ideological. First, just as Hizbollah (in Lebanon) provided social services such as hospitals, soup kitchens and so forth, Hezb u- Tahrir maintains that it is an entirely peaceful organization. Their goal is to reestablish the Halif faith. Halif in Arabic means “successor,” and this was the title given to the Prophet’s successor, leading the community.

The Halif faith was abolished in 1924 by Kamal Ataturk, and Hezb ut-Tahrir as well as other fundamentalist groups regard the Muslim community, the Umma, as indivisible, and that modern nation states are a corrupt Western innovation designed to bring down and separate the Muslim people.

Hezb ut-Tahrir wants to reestablish the Halif faith. Their belief is that if they can get a toehold in one country as a springboard, they’ll then gather force and eventually the entire Muslim world will be brought back into the fold. If you read their documents — their headquarters, by the way, is in Birmingham, England — but their documents are rabidly anti-Semitic, and their writings on what they will do once they establish the Halif faith, or reestablish it, state that every male from 15 onwards will be conscripted and will fight to establish Islam throughout the world.

SW: What you’re describing is quite different, let’s say, than the rebels in Chechnya, who are really fighting for national sovereignty, in a way, and a form of nationalism.

JD: The group itself came actually out of Israel; it was founded by a Palestinian in 1953. It’s banned in almost all Middle East countries as well as Central Asia. Russia has banned it, and Germany too, for its anti- Semitic character.

SW: Given this popular uprising where many people have been activated and have seen that they can be successful in overthrowing an oppressive and authoritarian leader who doesn’t respect free and fair elections, what chance really is there that a group like this could gain popular support — and what would it offer the population?

JD: When the Soviet Union imploded, Akayev got a free ride for some time because he blamed all the problems of the economy and everything else on the Communist system.

Well, after 14 years that argument is threadbare. For the average Kyrghyz, who heard about democracy in idealist terms, the experience he’s had of it has been very dissonant. Hezb ut-Tahrir on the other hand can say, “Well, it’s because you don’t live under a Muslim government and Muslim society that all these bad things are happening.”

So, in that sense, given that Communism failed, that democracy at least as it was practiced under Akayev has not delivered, the appeal back to historical roots where all the answers are to be found in the Koran, the Hadith and the Sunna, is going to resonate especially among young people who are searching for their spiritual answers.

SW: What role do you see for Russia in this, or do you?

JD: The fact that they have their airbase at Kan, the fact that the Shanghai Cooperation Organization is based in Bishkek, the fact that the Russians have rounded up hundreds of Hezb ut-Tahrir members in the last several years, indicates to me that they will monitor the situation very closely.

SW: Are you optimistic about the area?

JD: In my travels in central Asia, I’ve always been impressed by the genuine hospitality. The people there come from an ancient tradition, and it seems to me the majority I have met want what everyone else does: a decent job, a decent standard of living, and someone who loves them.

SW: Yes, I find that too.

JD: The women of the Soviet Union look only across the border to Afghanistan to decide they don’t want to wear burkhas, or into Iran and they don’t want to wear chadors. But having said that, the Soviet experiment really left a fairly large spiritual void in many people’s lives, which is very hard for Americans to understand because of the multiplicity of our religion. You need only look at the grief throughout Christianity on the death of the Pope.

ATC 118, September-October 2005