Against the Current, No. 93, July/August 2001

-

The Fast Track Attack

— The Editors -

Mumia Abu-Jamal's Case for Innocence

— Steve Bloom -

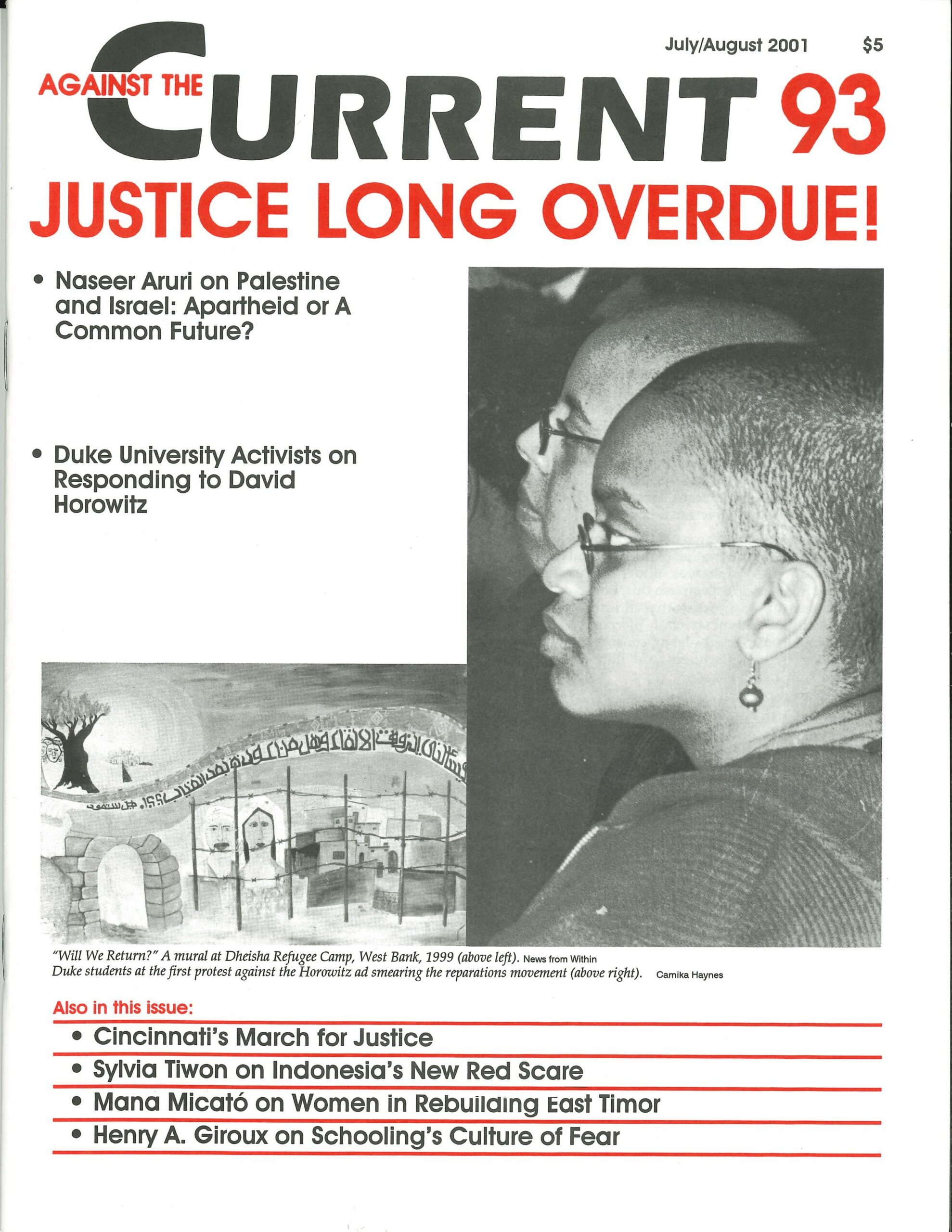

Duke Students Stand Against Bigotry

— an interview with Sarah Wigfall and Camika Haynes -

Cincinnati March for Justice

— statements by the organizers -

Asian Americans and "Pearl Harbor"

— Malik Miah -

The U.S. Movement Against Sanctions on Iraq

— Rae Vogeler -

The Kaloran Incident and Indonesia's Red Scare

— Sylvia Tiwon -

Women's Power for East Timor

— Mano Micató -

Russia's Education for the Market

— Boris Kagarlitsky -

The Second Intifada: An End and a Beginning

— Naseer Aruri -

Schooling Fear: Bush's Education Reform (Part 2)

— Henry Giroux -

The Photographic Art of Charles "Teenie" Harris

— Kathleen Newman -

The Rebel Girl: Women Rule the Waves

— Catherine Sameh -

Camera Lucida

— Arlene Keizer -

Random Shots: The Prices of Progress

— R.F. Kampfer - The Global Justice Struggle

-

One no, Many Grassroots Yeses

— Mike Prokosch -

From Populism Toward Anti-Capitalism

— Gerard Greenfield - Reviews

-

Labor's Change of the Century

— Stephanie Luce -

Karl Marx Backward and Forward

— Joe Auciello -

Ernest Mandel's Legacy

— Kit Adam Wainer - In Memoriam

-

Ibrahim Abu Lughod 1929-2001

— Salim Tamari

Arlene Keizer

The way of the Samurai is found in death. Meditation on inevitable death should be performed daily. Every day, when one’s body and mind are at peace, one should meditate upon being ripped apart by arrows, rifles, spears and swords, being carried away by surging waves, being thrown into the midst of a great fire, being struck by lightning, being shaken to death by a great earthquake, falling from thousand-foot cliffs, dying of disease, committing seppuku at the death of one’s master. And every day without fail one should consider himself as dead. This is the substance of the Way of the Samurai.

—Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai

THESE WORDS, IN voice-over, begin Jim Jarmusch’s 1999 film “Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai,” named for its main character (played by Forest Whitaker), an African-American hit man who follows the ancient Japanese code of the samurai warriors. He has attached himself as a “retainer” to a Mafioso named Louis (John Tormey), because eight years before the action begins, Louis saved his life.

One might think that bringing together the code of the samurai with the ethics of everyday U.S. urban life would play like a cheap gimmick or a source of humor; but Jarmusch has hit upon a brilliant method of elucidating the aura of death that surrounds the Black urban poor in this country.

In his groundbreaking work on slavery, Slavery and Social Death, sociologist Orlando Patterson has coined the term “social death” to refer to the condition of the slave. In all slave systems, Patterson argues, the slave has “no socially recognized existence outside of [the] master.”

Because slavery “always originated … as a substitute for death, usually violent death,” Patterson believes that we should view this condition as an attenuated death sentence.

The chain linking slavery with blackness has not been broken in the United States, and varieties of social death linger, making actual death more likely. Young Black men and women in many urban areas are marked down for death at an early age, a fact articulated eloquently and often in rap, an art form the jazz cornetist and bluesman Olu Dara, in his recent song “Neighborhoods,” calls “heavy-hearted young children’s music.”

Under these conditions, survival may feel like a miracle or an accident. For Ghost Dog to recognize himself as already dead is an acknowledgment of a social situation as well as an existential choice. The moment of his near-death at the hands of a group of white thugs, only averted when Louis kills one of them, appears to be the critical turning point for him; he relives it in his memory at two crucial moments in the film.

After the first hit we see him commit, he dreams about it, perhaps because of his encounter with the young, frightened girl/woman Louise (Tricia Vessey), who is present when Ghost Dog kills Handsome Frank (Richard Portnow). Later, as he goes to meet his certain death, a fate he understands and chooses, he sketchily tells the story of his almost-fatal beating, which we see again in flashback.

Moving through his poverty-stricken neighborhood to a haunting rap soundtrack (created by The RZA), sporting black clothing, cornrows (a hairstyle often worn by African-American men in prison), and a perennially somber expression, Ghost Dog embodies both the vulnerability and the power of invisibility.

Images in Flight

The film’s first image is of a bird flying, which is then crosscut with shots of the urban industrial wasteland below. This contrapuntal play of images powerfully calls to mind two precursors from African-American literature: Frederick Douglass’ view of the ships on the Chesapeake Bay and Bigger Thomas’ view of an airplane that passes over his southside Chicago neighborhood. These two Black men, 100 years apart, one enslaved, the other a fictional ghetto everyman, muse about their desire for freedom while watching the free movement of human-made vehicles.

We soon learn that the bird in the opening shot is one of Ghost Dog’s trained carrier pigeons, which represent his imagined freedom and serve as his means of communication with Louis. The film encourages us to read pigeons in general, not as “rats with wings” as many New Yorkers like to call them, but as analogues for the urban poor: usually grounded, sometimes reduced to scavenging, with the potential for flight.

Forest Whitaker is a large man who moves expressively, even eloquently. (Watching “Ghost Dog,” one can’t help remembering Whitaker’s scene-stealing turn in “The Color of Money,” where he hustles the hustler played by Paul Newman by exploiting cultural stereotypes about Blacks and the adipose-challenged.)

At several points during the film, Ghost Dog is linked symbolically to bears: His friend Raymond (Isaach de Bankolé), the Haitian ice-cream vendor, reads from a French book about the creatures, likening them to Ghost Dog; and on his way back to the city from Mr. Vargo’s mansion, Ghost Dog comes upon two white hunters who have illegally killed a bear out of season.

Their excitement over their kill is heightened by the fact that bears are rare, and Ghost Dog clearly feels the need to avenge the death of this fallen “brother,” a member of another group that is under attack from the dominant culture.

With the exception of Louis, the Italian American mobsters are capricious, indiscriminately brutal, and racist. Though they ordered the hit on Handsome Frank, because he was sleeping with Louise, Mr. Vargo’s daughter, they then decide that Ghost Dog must be eliminated because he killed “one of [their] own.”

Their treachery is contrasted throughout with Louis’ and Ghost Dog’s loyalty and honor. One mobster, Vinny (Victor Argo), shoots a female cop who stops them on the way to the hospital; he makes a cynical argument for female equality his justification for breaking an unwritten code forbidding the killing of women and children in mob violence.

The way in which the Mafiosi have abandoned their principles is part of a theme of degeneration that runs through the film. In one of his last speeches to Raymond, Ghost Dog says of himself and Louis, “We’re from different ancient tribes and now we’re both almost extinct. But sometimes you got to stick to the ancient ways, the old school ways.”

Disintegration

The samurai, Mafia, and urban African-American codes of conduct and honor are dissolving in a world turned upside down, a world on the brink of apocalypse. Perhaps the most telling symbol of that approaching catastrophe is the boat one of Ghost Dog’s neighbors is building on his roof.

Both Raymond and Ghost Dog wonder how the man will get the modern ark down to the water, but the film’s dark undertone suggests that an apocalyptic tide will rise to meet it.

Finally, “Ghost Dog” represents young women as the inheritors of men’s battles. An Afro-Caribbean-American girl named Pearline (Camille Winbush) befriends Ghost Dog, and he passes on his copy of The Book of the Samurai to her before he dies. She picks up his (unloaded) gun after his death and points it at a fast-retreating Louis.

Despite the fact that she is the daughter of Mr. Vargo (Henry Silva), Louise is linked to Louis by name. Portrayed throughout most of the film as a mentally unstable young woman victimized by having witnessed so much violence, she emerges as a player in her own right at the end.

In the film’s ambivalent conclusion, Pearline’s voice is the one we hear intoning lines from The Book of the Samurai: “The end is important in all things.” The best possible end “Ghost Dog” suggests is not a cessation of violence, but a change in the combatants and continuity between ancient and modern codes of warfare.

from ATC 93 (July/August 2001)