Against the Current, No. 80, May/June 1999

-

NATO's Road to War and Ruin

— The Editors -

Waiting to Inhale: Culture Wars or Unfinished Gratification?

— David Roediger -

The Fight for Leonard Peltier

— Hayden Perry -

CPE: Demystifying Economics--Interview with Elissa Braunstein

— Stephanie Luce -

Race and Politics: Indonesia's Ethnic Conflicts

— Malik Miah -

A Profile of East Timor's Jose Ramos-Horta

— Conan Elphicke -

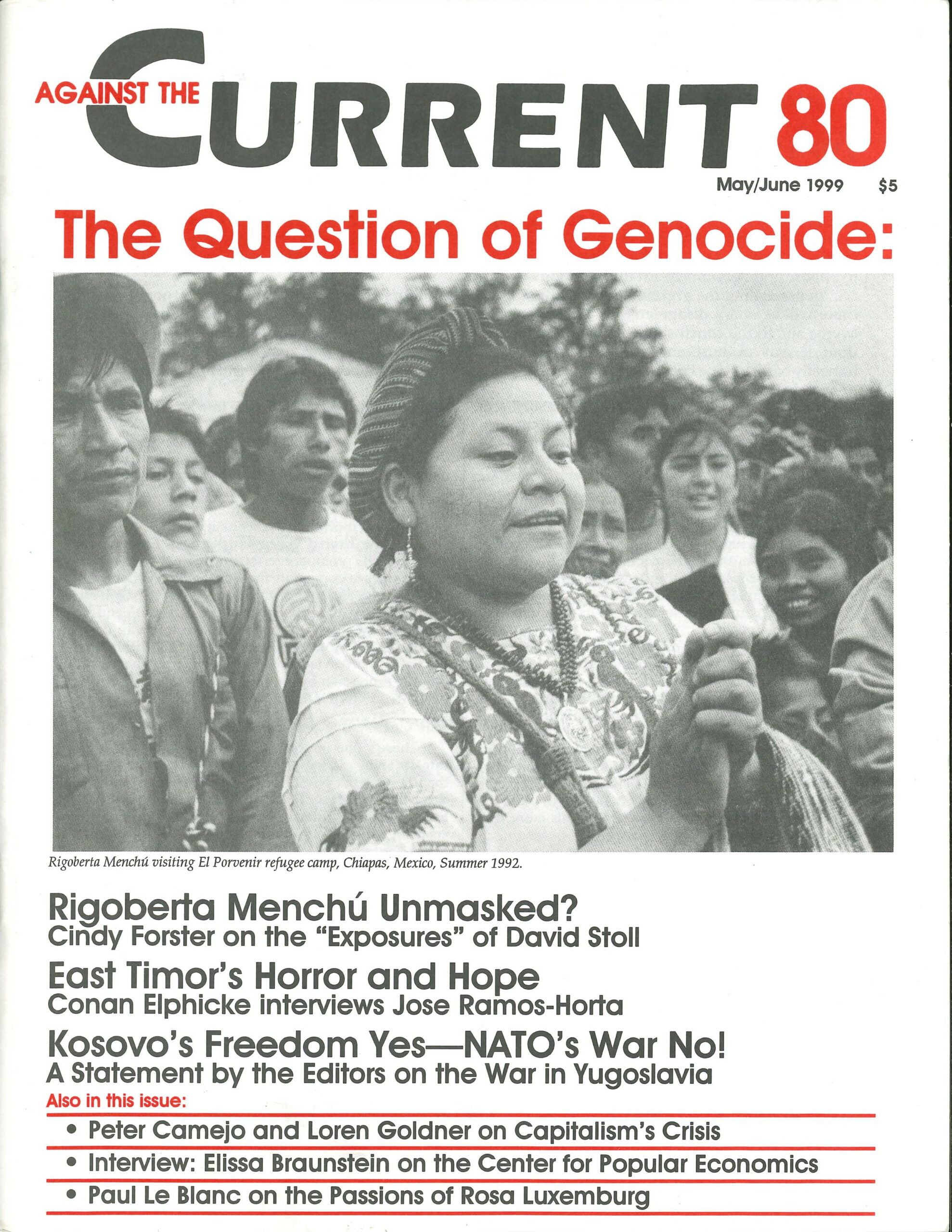

Rigoberta Menchú: A Witness Discredited?

— Cindy Forster -

A Revolutionary Woman in Mind and Spirit: The Passions of Rosa Luxemburg

— Paul Le Blanc -

Random Shots: Weird Sex and Boiled Bacon

— R.F. Kampfer -

The Rebel Girl: A Question of Rape

— Catherine Sameh - Capital's Global Turbulence: A Symposium

-

"Total Capital" Rigor and International Liquidity: A Reply to Robert Brenner

— Loren Goldner -

The Great Bull Market vs. Looming Crisis: On Brenner's Theory of Crisis

— Peter Camejo - Dialogue on Workers in a Lean World

-

On Workers in A Lean World

— Kim Moody -

A Rejoinder

— Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval - Reviews

-

Glaberman and Faber's Working for Wages

— Sheila Cohen -

The Availability of Utopian Thought

— Terry Murphy - Letters to Against the Current

-

Letter and Response on Mumia Abu-Jamal

— Sidney Gendin and Steve Bloom - In Memoriam

-

Comrade and Friend: Bob Strowiss 1919-1999

— Edmund Kovacs

Peter Camejo

THE UNITED STATES is experiencing the greatest bull market in the stock market. From a low of 776 in August 1982 the Dow-Jones Industrial Average has risen to over 9,600. [This article was completed prior to the Dow’s breaking the 10,000 barrier—ed.]

Two-thirds of this rise occurred during the 1990s. The stock market is a leading economic indicator. Therefore, one could argue that the market is predicting an expansion in production, a rising Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and increasing profits. Is the market wrong this time?

In this commentary I want to discuss the power of the present bull market and how it relates to the thesis Robert Brenner presented in his recent article (ATC 77, November/December 1998), “The Looming Crises of World Capitalism: From Neoliberalism to Depression.”

Brenner concludes that the bull market’s prediction of economic expansion is probably wrong. Of course, Brenner wrote the ATC article during a sharp market drop, which he saw as confirming other indicators of a U.S. economic downturn.

In both his ATC article and his longer essay in New Left Review, Brenner presents a formidable case that time is running out with the “U.S. economy’s slipping toward recession or worse.” His thesis is based on the view that capitalism is in a developing crisis caused by world overproduction and overcapacity, a declining rate of productivity growth, and lower profit margins.

A Cycle of Expansion

I believe that Brenner may be wrong, at least in his timing of an immediate major down turn in the United States. We may be in for a short period of recession or an earnings slowdown in 1999, but we are not, in my opinion, at the beginning of another period like that of the 1930s or 1970s. On the contrary, U.S. capitalism is probably in the middle of a major expansion cycle that may have quite some time to go.

People who try to predict the future all have one thing in common: They are, over any extended time period, wrong. But such efforts are valuable if they identify emerging trends and stimulate us to think about where they may lead—and Brenner does this effectively.

I come to different conclusions, however, based not on a critique of his analysis but because I question the validity of the data Brenner relies on. In addition, I suggest that the technological revolution has an important role in explaining why some data may be misleading, and why the economy’s positive momentum may continue.

As I noted, Brenner published his article in ATC right after the sharp market drop of late summer/early fall. He concludes that the U.S. manufacturing boom has ended as a result of intensifying international pressure from overproduction and overcapacity.

This shift, Brenner postulates, has “wide-ranging implications for the economy, the most important of which has been the bursting of the stock market bubble.” Later he adds:

To make matters worse, the end of the stock market bubble has brought a tremendous loss of business confidence, and lenders, doubting the ability of their creditors to repay, are calling in their obligations in panicky drive for liquidity . . .”

That must have sounded accurate if you read Brenner’s article on October 8,1998, as the S&P 500 bottomed at 925, but by the end of the year the S&P 500 was making new highs around 1230, some 30% higher. (Most ATC readers will be more acquainted with the smaller index, the Dow-Jones Industrial Average, which bottomed at around 7,400 in October and but ended the year making new highs above 9,300.)

Third-quarter GDP turned out to show a quite good 3.9% growth rate. Housing starts and auto sales were also strong in the third quarter. At least through the fourth quarter there is no sign of a major slowdown in the United States. The official unemployment figure is under 4.5% These are not the signs of an economy in trouble.

Early statistics in 1999 reconfirm the strength of the U.S. economy. This year, 1999, will be the fourth year for which most economists have predicted a downturn in the U.S. growth rate. Although they have been wrong for the last three years, as we enter 1999 they are once again predicting a slowdown from about a 4% growth rate (quite high) to about 1%.

Sooner or later, of course, they will be right. Brenner differs from the consensus in seeing a negative GDP growth in 1999, that is a “recession or worse.”

But if we were about to enter a recession, why did the market rebound so fast—even breaking the highs set in July before even three months had passed?

What, if anything, did the market drop signal? Or better put, why did the market make such a violent V-shaped correction (V-shaped corrections are typical of a rising market), which took the average stock down about 30% and the NASDAQ stocks about 50%—but only for a few weeks?

Was the market predicting a coming economic slowdown, or was this just a technical adjustment after seven years of continuous rise without corrective intervals? In other words, was the drop only a normal correction within a long-term upward trend that took on a rather sharp and violent nature because of the unusually strong upward thrust?

In recent history, market drops have predicted economic downturns about once for every two drops. The stock market tends to make a 10% correction every 18 months and a correction of more than 20% about once every three years. Neither sort of correction occurred from 1991 into 1997.

Productivity: Increasing Dramatically

My questioning of Brenner’s conclusions includes both differences on material facts and conclusions based on existing information.

To summarize: I do not agree that productivity is declining, that the U.S. savings rates is dropping sharply, that major corporations have been using their high-priced stocks to raise capital, that profits are declining, that the existence of overproduction and overcapacity is as meaningful as Brenner (and others) think, or that the U.S. stock market is in a “bubble.”

The key point stems from a major factor hardly mentioned by Brenner: We are living during the greatest technological revolution of all time, based on the microchip and other advanced technologies, and one that will continue into the foreseeable future.

This revolution is dramatically increasing the productivity of labor. The traditional indicators used by today’s economists, in my opinion, are unable to measure what is happening. The fact that some statistics may show little productivity gain through the introduction of computers only proves to me that the methods of measurement are failing to describe reality.

We are not talking about minor changes here. We are living through macro changes similar to the appearance of the cotton gin, which made it possible to complete in one hour work that formerly took 1,000 hours, thus revolutionizing the South’s economy in the early 1800s and facilitating the rapid expansion of the textile industry in Britain and New England (and, of course, of slavery in the South).

Today’s revolution is of such a magnitude that it is unmeasurable. What does it mean to say we can now do things 1 million times faster? How do you measure productivity gains when computers make it possible to do things otherwise impossible?

In many cases the gains in productivity pass through to the consumer as use value, and are poorly reflected in profits. All kinds of economic relations are being altered at incredible speed. For example, these changes are lowering the cost of production all across the board. They are internationalizing the labor market, which in turn creates a powerful downward pressure on wages in the advanced industrial nations and blocks the appearance of inflation despite economic expansion—while creating pockets of rising wages in sectors within developing nations like South Korea.

These economic/technological trends leave out large numbers of people who, at least for the moment, still live within the framework of the old economy. Given the market-driven nature of capitalism, rapid technological changes inevitably lead to sharp dislocations and much human suffering.

Technological advances create important potentials for improving the quality of life for all, but capitalist society focuses only on the profit potential.

When the mail in Seattle is sorted electronically by workers in Mexico City for one-tenth the cost, and North American car insurance policies are processed in the Philippines or Ireland, economic relations change and statistics intended to measure them lose their accuracy.

The fact that your car’s brakes prevent you from skidding and maybe save your life is important for you, but the auto manufacturer may not have been able to gain much profit from this innovation. On the contrary, it had to introduce antilock brakes just to keep up with competitors.

Since antilock technology (based on microchips and sensors) was not previously available in conventional brakes, there is nothing to measure against.

The financial gain from the development and introduction of antilock brakes was made by the corporation providing a capital good, in this case embedded software, which involves little actual physical equipment.

This is why profits have been shifting towards technology companies and away from end producers (manufacturers). A declining rate of profit in “manufacturing” may have a different meaning than it did in the 1940s and 1950s, and therefore may not give the same overall picture of the economy that it once did.

The ability to move capital in massive amounts in a matter of seconds has created imbalances that can create liquidity crises overnight. The power of computerized international debt and equity markets is destroying the sovereignty that we associated with nationhood just 30 years ago. Countries are becoming helpless before the power of international markets that alter their interest rates and the value of their local currency, and can suddenly paralyze their economy or create a short-lived boom.

Our culture, our lifestyle, our quality of life, even the forms of political life are presently in rapid transformation both here and internationally.

Corporate Profits And Capital Burn

The profits of U.S. corporations are making new records. The idea that profitability is declining depends on how one measures profits.

When measured as a percentage of GDP, profits in the United States have been pushing upwards throughout the 1990s. Profits tend to vary between 4% to 8% of GDP. They are currently nearly 8%.

Rather using a traditional measure like profits as a percentage of invested capital, it is now more useful to look at free cash flow, since corporations often try to hide their profits to avoid taxes.

The issue of overproduction and overcapacity is one of the most interesting in the midst of the chip revolution. Product after product are becoming commodities that are undifferentiated by producer, and therefore produced and sold on tiny margins. But all this is occurring within the framework of a rapidly changing production environment.

The burn rate of capital investment—that is, the rate at which production facilities become obsolete—is at an all-time high and there is no sign that the tempo will slow. This is partly because each generation of computers and related software and hardware is quickly succeeded by a new generation that is faster.

It is true that computer hardware and software by themselves still account for only a small portion of capital investment. But the key point is that virtually all new productivity-enhancing equipment and techniques depend on computer coordination and control, with computers being linked to and embedded in production facilities at all levels.

Rapid changes in computer technology thus mean that production facilities of all kinds that depend on computer control become obsolete very quickly.

When the Asian currency collapse occurred, economists immediately predicted the flooding of the U.S. market with cheaper products stifling U.S. producers. The Koreans, it was predicted, would flood our markets with low-priced computer chips, computers, and phone equipment.

This prediction may be inaccurate, however, because the Koreans’ ability to produce goods is compromised at an incredible speed by their inability to compete unless they upgrade their productive capital. The Koreans can produce a chip for only one or two years before they are out of business unless they buy new equipment to make new and better chips.

Statements that we face “overcapacity” at any given moment are thus like a still picture in a fast-forward video. Production capacity that is not constantly renewed by investment disappears in a way unheard of in previous generations. In fact, we are witnessing a drop in exports from some of the Asian countries since they cannot find the capital to renew their productive capabilities.

U.S. Economic Strength

The threat to U.S. capitalism because of the crises in Asia and their temporary overcapacity is therefore not half as dangerous to the viability of the U.S. economy as the media have made out.

For the last eighteen months everyone has been waiting for the world crisis to hit the United States. It will, but it is very difficult to figure out exactly how and to what degree.

For the present, the strong dollar and the enormous capital reserves of U.S. corporations have given U.S. capitalism an advantage over Japan and Germany. U.S. corporations are taking advantage of the crisis in Asia to buy up productive capacity at major discount prices, knocking out Japanese and other competitors. General Electric, as one example, just went on a major buying spree (I believe some $20 billion worth) in Japan itself.

The United States is in the command position of capital internationally with the strong dollar, a strong military, and strong balance sheets. Even the U.S. government, under corporate CEOs’ presidential darling Bill Clinton, has shown an unexpected budget surplus of sorts. If anything, the crisis in Asia is shoring up the domination of U.S. capital internationally.

It is unclear how this crisis will continue to unfold. It is not possible to rule out a growing breakdown that leads to a worldwide recession or depression, proving Brenner’s outlook correct. However, I lean towards the view that it will not bring the U.S economy down.

To understand the interrelationship between the U.S. and the Asian economies, it is important to keep in mind their relative size. For example, the equity markets of South Korea, Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, Hong Kong and Malaysia all added together do not equal the capitalization of General Electric, just one company in the S&P 500.

While I do not challenge that the dislocation created in Asia for a series of reasons can lead to a slowdown in the United States, I doubt such a slowdown will lead to much more then a mild recession at this time. It would be peculiar for the secular expansion that began in 1982 to end after only sixteen years.

Later, I believe, things will be different. Capitalism has not resolved its internal contradictions. Taking a longer view of these developments, we should also note that today’s economic boom for U.S. capital (something very different from prosperity for all the people who in habit the planet) is based on the rape of the earth’s unrenewable resources.

Savings, Facts vs. Myths

A current economic myth has it that U.S. citizens are not saving, and in fact recent articles have claimed that the savings rate has become negative. The fact of the matter is that U.S. citizens are saving and that corporations are buying, not selling, stocks.

Here is how Brenner refers to the U.S. savings rate: “With stocks so high, consumers had thought their wealth so increased that they did not need to save, and by profoundly reducing their savings rate. . .”

Brenner also took the high stock market to mean that “. . . With stocks so high, corporations could much more cheaply raise money by selling shares, so investment has accelerated. But with the stock market falling, these so-called `Wealth effects’ have gone into reverse.”

These comments by Brenner are both factually wrong. U.S. corporations have not been using the high price of stocks to raise money by selling shares, and the rate of savings may actually be increasing because of the rise in the stock market.

U.S. corporations since 1982 have been net buyers of stocks. This has been an important underpinning of the present bull market. Even after an over tenfold rise in major indexes, corporations are buying still their own shares in the open market.

When you compare the purchases by corporations of stock with the sales of new stock issues (what are called IPOs—initial public offerings), capital remains a net buyer of stock. Corporate America is cash-rich and considers stock as one of the best investments available.

Thus it is wrong to imply that high stock prices have led to corporations rushing to sell stocks to raise capital. The total amount of equities available in the stock market has actually declined during this bull market.

Further, the important lead indicator of insider buying or selling was at the end of 1998 sending a strong buy signal. Insiders, who traditionally have a good record of predicting their own companies’ fortunes, are busy buying, not selling, their own shares.

One of the reasons corporations buy their own stock is the double taxation on dividends. They find it more effective to increase the value of their shares to benefit shareholders than to issue dividends.

This has led to large capital gains for the rich with reduced capital gains taxes. It also has the effect of helping to raise the price of the stock market as a whole by lowering the price-to-earnings ratio (P/E), even if earnings remain constant.

The statistics on savings have become skewed by the rising market. These statistics subtract the tax bite of a capital gains sale from an individuals’ income, which immediately appears against savings, but do not credit the gain. Thus, when a capital gain of one dollar is taken it lowers savings by twenty cents—but the eighty-cent gain is not measured as either income or savings (see Gene Epstein, Barrons, December 21, 1998, page 3.1).

Other faulty mathematics lead to misstatement of savings, such as categorizing home purchases as purely consumption instead of as an investment. For most people the equity in their home is a major form of savings.

Half of the people in the United States live from paycheck to paycheck. Many of them own a home. Their mortgage payment is often their only form of savings, since part goes to increase the equity in their home. These savings are not counted in the savings statistics compiled by the Commerce Department.

The fact is that U.S. citizens on the average have a larger “savings” account than those of any other country, almost 40% higher than supersaver Japan.

Obviously most of these savings are concentrated in the upper strata. For those with incomes above $70,000, the present savings rate is 25%. The overall savings rate remains positive at 5% to 10%, not negative.

We Are Not in a “Bubble”

“Bubble” is the wrong word to describe the broad U.S. stock market. The concept of a fair value for a stock is related to the return on investment in comparison with alternative investments. The key comparison used is risk-free U.S. government notes and bonds: If you pay $10 a share for a stock and bonds return 5% risk-free, then risk-adjusted your return should be 5% or higher, say 7% or 8%.

Of course, the above comparison assumes no appreciation in the price of the stock. If the company’s revenues and earnings are expected to increase, leading to an increase in the price of its stock, then the risk-adjusted fair value return for an equity can actually be under 5%.

In the end, money goes where money is made, risk- and growth-adjusted, period. Exceptions are always temporary, and there are always some exception—such as today’s mania for Internet stocks.

But what about the hundreds of stocks projecting in the immediate future earnings, say, of 10% after taxes, and growing in the context of little inflation and a 5% government bond rate? Are these stocks overvalued? Obviously not—unless one expects a deep depression and a collapse in earnings, or a sharp rise in inflation and interest rates.

Markets do overshoot on the upside and the downside. Imbalances appear, and we do have some at this time. We have a phenomena known as the “nifty fifty,” which has made some indexes such as the NASDAQ 100 and the S&P 500 overshoot somewhat, while broader indexes such as the Russell 2000 are undervalued.

Except for Internet equities we do not have a “bubble” at this time relative to earnings or revenues. The S&P 500 may be overvalued by about 20% (just its gain during 1998) if we have a downturn in earnings in 1999; but that does not qualify for bubble status.

The rule of thumb on Wall Street is to multiply U.S. government interest rates by .76, invert the number and multiply by 100 to get a price-to-earnings ratio. If we do that with interest rates at 5% we get a 26 P/E.

Estimates for 1999 earnings for the S&P 500 are over $50, which at a 26 P/E gives us an S&P 500 of at least 1300, whereas the S&P 500 was at 1230 at the end of 1998.

Edward Yardeni, who is predicting a worldwide depression, in part because of the Y2K issue, estimates $35 in earnings for the S&P 500. That would give us 920 on the S&P 500, or about a 25% drop. A drop to 920 would only put us back to where the market dropped on October 8, 1998.

This does not qualify as a “bubble.” The market records a decline of over 20% on average every three years. The term “bubble” is appropriate for periods when prices of stocks have become completely disconnected from their underlying value. The term thus describes the potential for a massive collapse, to return to a relatively fair valuation in relation to other assets.

We need to consider also what will happen if interest rates continue their long-term downtrend, associated with the deflationary impact of the microchip revolution. Interest rates traditionally average 3% above inflation, which at the present Consumer Price Index could bring interest rates down blow 5%.

At 4% interest rates, even Yardeni’s figures put fair value at 1155 for the S&P 500—only 6% below where it ended 1998.

Long-Term & Short-Term Cycles

To understand the present bull market we need to take a step back and see what has happened to the stock market this century. Everybody knows the year 1929, the year the market crashed. But profound market drops, which occur about once every forty to fifty years, can take many forms.

The market in 1929 dropped 89% from top to bottom. From 1966 to 1982 the U.S. market dropped, inflation adjusted, by 75%—almost the same as the 1929-1938 bear market, but hardly anyone refers to this drop in the same sense, in part because the U.S. economy did not experience an economic crisis of the same magnitude as during the 1930s.

Adjusted for inflation, the U.S. stock market recouped where it had been in 1966 only in the year 1996! That is an amazing statement. In those thirty years, didn’t the largest 500 corporations of the U.S. gain in value adjusted to inflation? Well, the market only began to reflect that value in 1996.

We are living in a world where the potential to produce a rapidly growing list of products to fully meet the existing market demand can remain constant without the traditional inventory recession or depression cycle hitting the economy.

The short-term business cycle appears to be shifting. The traditional four-to-five-year business cycle seems now to have stretched to eight or so years, but has also smoothed out bcause of computers.

Today, the moment you buy something at the supermarket the inventory is adjusted and an order to replace your purchase is under way. Thus the traditional cycle of “things are selling, let’s buy more—oh, oh, we overbought, stop ordering” is buffered. We are not having inventory-related recessions.

Statistical Measures in Crisis

One of the traditional market indicators used to determine whether the stock market is overvalued or undervalued is book value. Traditionally, the market would vary between one to two times book value. Thus, when the market traded at one times book value it was undervalued, and above two times book value it was overvalued.

During the present bull market under the impact of the chip revolution the market went right through two times book value and has continued to rise, breaking records year by year. The mystery to this change may be that we no longer know what book value is.

Take the example of Microsoft. What is Microsoft’s book value? In the past, book value had to do with the value of buildings, machinery, land, and cash on hand minus liabilities. But Microsoft has little invested in equipment or buildings. So it trades at a huge ratio to its formal book value.

Marx saw economic relations as a “veiled expression” of human relations. One of those relations was the law of value: the concept that in the end exchange value is related to the cost in human labor time to replace a product.

Capital, to Marx, was accumulated human labor time. A piece of machinery has an exchange value based on the (human labor) time necessary to replace it.

In Marx’s day, most jobs in manufacturing industry required only a short period to master. Certainly, when the early 20th century saw the establishment of mass production factories, most jobs could be mastered in relatively brief training periods and the cost to train an employee would be minimal.

In today’s world, employees at Microsoft cannot just be replaced and trained in a week or a month or six months. Employees bring with them large amounts of education, some socialized, some paid for by previous employers and some paid for by the employee.

Is it possible that the cost to learn the skills necessary to work is a form of capital that depreciates based on the time left to work in one’s lifetime? If so, Microsoft may have a much larger book value then it appears, partially capitalized by society.

Maybe the ratios of capitalization have not really changed so much. The change may be that the education factor is rapidly increasing and it is simply not counted.

Is there a capital cost in the skill level of a worker? I think so. At this time there are about 360,000 jobs in information technology that cannot be filled because workers with the necessary knowledge are unavailable. Some firms like Systems and Computers Inc. claim their growth is limited only by their ability to hire more qualified employees. They have to allocate part of their investment capital precisely to train new workers.

Such costs are far higher today than in the past. That expenditure is booked as an expense, not as a capital item like the purchase of equipment or a new building.

The Liquidity Crisis

Brenner mentions the current liquidity crisis, which has been most pronounced in Asia. He describes eloquently the shift now taking place as the leaders of the G7 try to stimulate the world economy by increasing liquidity, lowering interest rates worldwide as well as moving to increase fiscal stimulation, especially in Japan.

As Brenner notes, this is a sharp turnaround from the original “shock therapy” IMF approach. Whether they succeed in turning around Japan and the other Asian countries has yet to be seen.

Brenner details this shift in his ATC article, but questions whether it can alter the negative dynamic under way in much of the world’s economy. I am not sure to what extent the new turn will work to stimulate the world economy, but the turn is definitely happening, and with all kinds of political consequences.

Concluding Remarks

I want to thank Robert Brenner for the in-depth study he has done to document long-term postwar economic trends.

As he says at the beginning of his article in ATC, the left has traditionally predicted international economic crises that never occur. That history should stimulate us all to carefully analyze current trends, especially since they offer so many new features that are not accounted for in conventional theories or statistics.

I am in full agreement, however, with Brenner’s underlying thesis that there are problems brewing that a market economy cannot solve, which will inevitably bring down the present stability and relative prosperity.

It is a matter of time. And, I would add, if you factor in the environmental dislocations under way, the next century could see crises of a magnitude and in forms unknown in our lifetime.

ATC 80, May-June 1999