Against the Current, No. 69, July/August 1997

-

The Republicrats' Phony Budget War

— The Editors -

The Los Angeles Bus Riders Union

— Scott Miller -

The Consumer Price Index "Reform"

— James Petras -

Britain's "New Labour"

— Harry Brighouse -

Woman-Centered, Activist Agendas

— Deborah L. Billings -

The Remaking of the Congo

— B. Skanthakumar -

The Roots of the Rebellion

— B. Skanthakumar -

Kabila's Friends

— B. Skanthakumar -

Mobutu's Loot and the Congo's Debt

— B. Skanthakumar -

Humanitarian Intervention

— B. Skanthakumar -

The AFDL and Its Program

— B. Skanthakumar -

Mining Congo's Wealth

— B. Skanthakumar -

Pornography, Violence and Women-Hating

— Ann E. Menasche interviews Diana Russell -

The Rebel Girl: Looking at the Gender Grid

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Fables of Bill and the Newt

— R.F. Kampfer - Exploitation and Upsurge

-

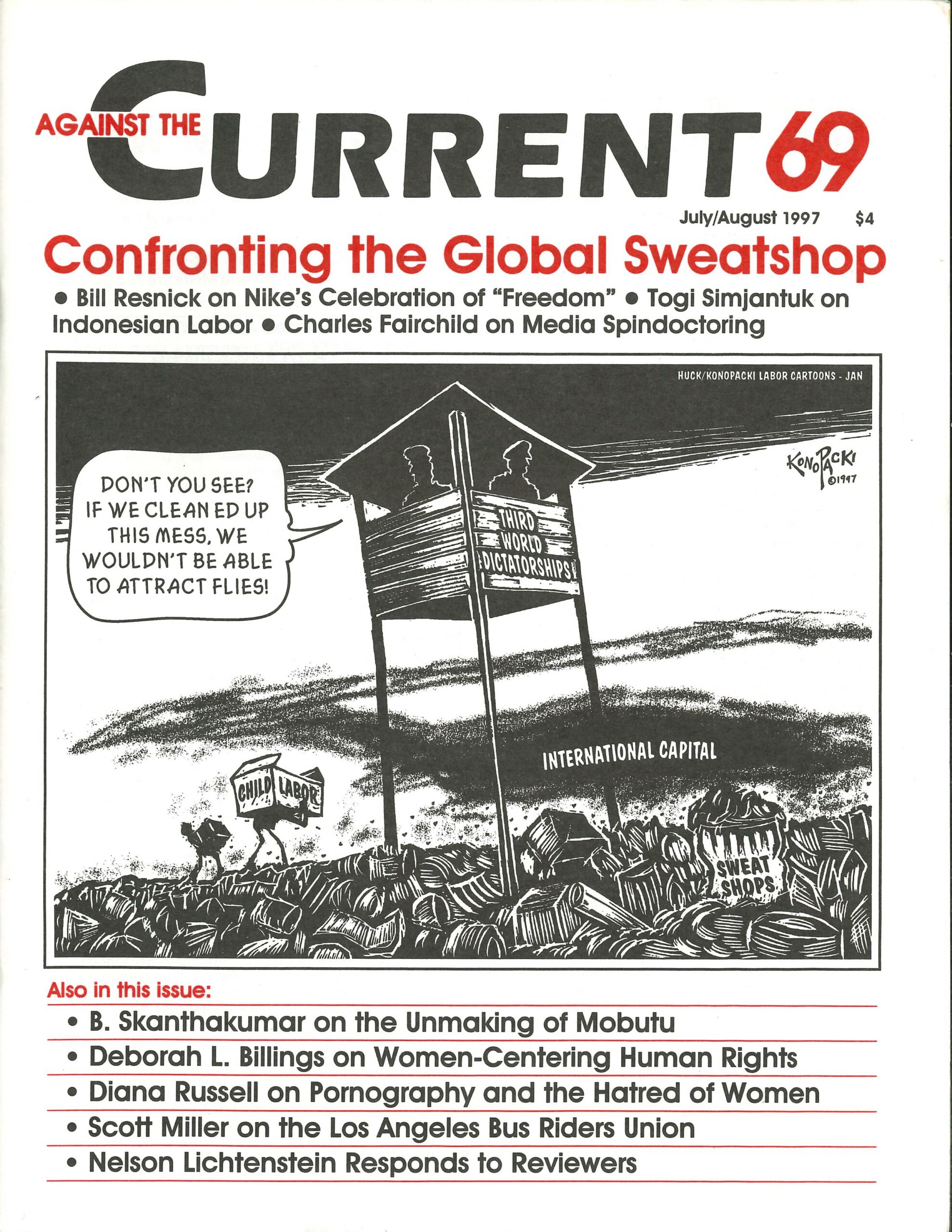

Global Sweatshops' Media Spin Doctors

— Charles Fairchild -

Socialism or Nike

— Bill Resnick -

Indonesia's New Social Upsurge

— Togi Simanjuntak -

Fellow Workers, Fight On!

— interview with Muchtar Pakpahan - Reviews

-

Asian American Incorporation or Insurgency?

— Tim Libretti - Dialogue

-

A Response to Reviewers

— Nelson Lichtenstein - In Memoriam

-

Albert Shanker, Image and Reality

— Marian Swerdlow and Kit Adam Wainer

Charles Fairchild

RECENTLY, TWO NEWS items briefly pierced the deafening silence surrounding the issue of cheap labor in poor countries.

* The first was a February 27th story presented on the Pacifica Network News, which reported that labor activists in Haiti continue to be routinely fired by their employer, a Disney subcontractor, for the mere threat of a work slowdown and the slightest whiff of union organizing. While the firings violated Disney’s “rules” on subcontracting, the company has shown little tangible concern for their indirect employees.

A Disney representative interviewed for the story came prepared, of course, citing the work of an intrepid reporter from Grand Rapids, Michigan, who was graciously provided a tour of the worksites in question. He had reported back to his employers that all was well.

* The second was a story of April 15th. Most major American papers reported that President Clinton and selected garment manufacturers had announced the “Apparel Industry Partnership.” This voluntary agreement stipulates that the nine signatory companies must pay the prevailing minimum wage in the countries in which they operate, limit the work week to sixty hours, and bar those under age 14 from working in clothing factories. The companies themselves are responsible for enforcement of this sincerely weak agreement.

On the whole, however, there’s an imposed silence about the steadily increasing number of low-wage factories being set up in poor countries by wealthy multinational corporations: the “debate” is over. Press coverage of the “real story” was carefully used to settle the issue.

Two suspiciously placed articles put out by the New York Times News Service (7/20/96) and the Washington Post (7/28/96) last summer are indicative of this backlash against critics of multinational corporations, a backlash which was characteristically brief and vicious.

These articles are clearly the products of the well-worn “news management” technique in which PR firms give “journalists tours” of a company’s operations and allow them “reasonable access” to a select number of employees. It is important and useful to see how the numerous issues surrounding the use of cheap labor, workers’ rights, and prospects for a democratic workplace in an era of “free trade” are massaged and framed through such endeavors.

I’ve chosen to concentrate on these two relatively dated articles because they fulfill, with disturbing thoroughness, the most important rules of corporate “news management,” articulated with admirable precision by business consultant P. Prakesh Sethi in his book Advocacy Advertising and Large Corporations. Sethi suggests the following to his clients:

“1) Do not change performance, but change public perception of business performance through education and information. 2) If changes in public perception are not possible, change the symbols used to describe business performance, thereby making it congruent with public perception. Note that no change in actual performance is called for. 3) In case both (1) and (2) are ineffective, bring about changes in business performance, thereby closely matching it with society’s expectations.”

Managing the News

As the following analysis of the Times and Post articles shows, the corporate offensive never even got to Stage 3. What Sethi calls “the legitimacy gap,” that vexing disjuncture between performance and perception, was bridged with a few slight dispatches from overseas reporters. The arguments contained within their articles were widely distributed and amplified to the exclusion of other less acceptable ideas.

The New York Times article examines clothing factories in Honduras and begins by introducing readers to the benefits of the global economy. The scene is one of workers arriving for the morning shift at a plant in San Pedro Sula where “anxious onlookers are always waiting hoping for a chance at least to fill out a job application.” While the article notes that the plant only pays about forty cents an hour, we are assured that those who work there come from jobs that pay even less and offer even less security or fewer benefits; thus they “see employment here as the surest road to a better life.”

The other employment and “security” options available in Honduras are left to the readers’ imagination. We are comforted by the knowledge that what we might see as exploitation is actually upward mobility. Thus the vast majority of the article is relentlessly upbeat, citing how corporations are successfully fighting a Honduran unemployment rate of forty percent.

The Times’report argues both implicitly by demonstration and explicitly by quotation that “the U.S campaign [against sweatshops] may actually be hurting the very people it is intended to help.”

The only criticisms come from the National Labor Committee, which has called these operations the “monstrous sweatshops of the new world order,” a claim that is made to look ridiculous in contrast to the overwhelmingly cheerful survey of workers and corporate executives. Indeed, with the exception of one remarkably clear and important sentence by the executive director of the NLC, one could be excused for leaving this fairly long article with a vaguely munificent feeling of “American exceptionalism” in world affairs, an idea which goes virtually unchallenged here.

The workers interviewed for the article are uniformly positive about their work experiences; the only criticism cited comes from the second-hand congressional testimony of a 15-year-old worker who noted several abuses at a Honduran factory. It is clear from the framing of worker testimony that the Times reporter did not talk to a single worker away from the factory, nor did he speak to anyone who was not placed in front of his tape recorder by corporate management.

The few criticisms that were allowed to surface were immediately explained away by Paul Kim, the president of the Korean company Global Fashion, who owns the factory in question. He denied that any abuses had ever occurred there and claimed that the work regimen used by his company is just the kind of “tough love” Central America needs if the region is to become as prosperous as Korea.

Of course, Korea’s affinity with Honduras doesn’t just end with a penchant for hard work and upward mobility as both countries are only now showing signs of emerging from brutal military dictatorships. Apparently, Korea’s form of “tough love,” inflicted on its own population, was only a minor factor in its economic growth as it goes unmentioned here.

Spinmasters Vs. Reality

The Times piece ends by describing a “competitive” Honduran labor market in which wage earners are ceaselessly on the move, always seeking the best hourly rate. Local unions are concerned only with the enforcement of existing labor laws which supposedly guarantee the right to organize, restrict the worst abuses of child labor, and correct substandard working conditions. Given the Honduran government’s past relationship with unions, however, vigorous enforcement seems doubtful at best.

The Post article is virtually identical in form and content, with the exception that it examines a Nike factory in Indonesia. Again the dispute is reduced to its barest essentials: critics claim that American corporations “exploit underpaid workers to maximize profits back home,” while Nike claims that “American investment in such countries as Indonesia has placed those countries on the road to prosperity.”

Somehow the Post’s reporter is able to frame these two sentiments in a classic “telling both sides of the story” routine despite the fact that they have nothing to do with one another. It should also be noted that prosperity” in Indonesia means making about $2.28 a day.

Corporate officers further seek to assure those who might be queasy about $100 shoes made by people who are paid even less than their Honduran counterparts by claiming that workers have been randomly polled by an “independent” accounting firm and they are happy. Besides, history is on Nike’s side. “If light industry didn’t go into developing countries, people would still be trying to scratch a living off the land.”

“We’ve all studied this in economics,” says a Nike executive, “this is how industrial revolutions start.<170> This neat revision of history, presented without challenge or rebuttal, is apparently sufficient justification for whatever abuses of power that might occur in the pursuit of “development.”

Unfortunately, for the Post, on the same day that their Nike article appeared, a lethal irony was playing itself on the streets of Jakarta. In order to prevent an actual political opposition from developing, the Indonesian Army launched a preemptive raid on the offices of the officially-sanctioned Indonesian Democratic Party, attacking demonstrators, and hauling hundreds of pro-democracy activists off to prison. After the ensuing riot was quelled the leading trade unionist in the country was arrested at his home and charged with subversion, under an old Dutch colonial law that carries the death penalty.

The next day the army said it was prepared to shoot any “troublemakers” on sight. The Post’s headline read simply “Opposition Supporters Rampage in Indonesian Capital.” Little context was supplied to explain the roots of the conflict. Given the harrowing choices provided by the Post, working for peanuts in a Nike plant appears to be a comparatively safe and attractive option.

Why No Choice?

Neither article makes even the slightest attempt to look at the possible reasons why people in poor countries are willing to work for such appalling wages, regardless of any comparative “benefits” they might receive as a result. For example, both articles note that rural workers are leaving the countryside because most simply can’t survive the chronic malnutrition and overwork such a life offers, especially when they’re working somebody else’s land. But neither reporter asks why nobody can seem to survive in the rural areas of countries that have a fair amount of workable land and probably enough natural resources for at least some reasonable part of the population.

What both Honduras and Indonesia are extremely short of is obvious: democratic institutions and equitable distribution of resources, especially land. In fact both countries have fought long civil wars in recent decades against exactly these possibilities supported in full by successive U.S. administrations.

Instead, each country has followed the prescriptions of the IMF and the World Bank, whose economic programs call for the dominance of export-based agriculture produced for American and European agribusiness, the eventual abolition of subsistence farming, and the creation of a wage-based economy.

While the cash wages collected in factories may be higher than those available in the country, this is only because other options have been foreclosed. These other options remain untried precisely because they run counter to the interests of employers and raise such troublesome notions as autonomy and self-determination.

The central argument in support of massive foreign investment and related industrial relocation, cited above, has been historically anointed as the only road to prosperity. But other forms of aid have been shown to be far more successful in directly helping the greatest number in ways that do not subject existing social institutions and ways of living to permanent dependence on fickle Western capital.

For example, Dr. Mohammed Yunus’ Grameen Bank has been a leading “micro-lender” for decades. Yunus has found that giving small amounts of money to individuals to enable them to solve what appear to us to be small problems in local economies has been the most successful form of economic development yet tried in his perpetually poor country of Bangladesh. Ninety-seven percent of Grameen loans are repaid, meaning, of course, that almost everybody who has tried micro-lending has been helped by it. Too bad the IMF cannot say the same.

Wage-labor does not necessarily mean greater prosperity, only a regular paycheck for those who aren’t “troublemakers” and a basic dependency on the whim of financial markets and currency speculators. The Americanization of labor around the world spells the continuing destruction of social, political, and cultural structures, and their replacement with Western models of social stratification. This grand project of domination is at work both home and abroad and there is a fight on to keep it nice and quiet.

July-August 1997, ATC 69