Against the Current, No. 65, November/December 1996

-

The Gulf Slaughter Revisited

— The Editors -

The Poisoned Fruits of Oslo (II)

— The Editors -

For Iraqi Children, Death by Sanctions

— Stanley Heller -

The Vulnerable Are 70% of the Population

— interview with Professor Peter Pellett -

Jerusalem's Inevitable Explosion

— David Finkel -

The Strike at McDonnell Douglas

— Peter Downs -

HMOs, A Pox on Our Houses

— Pauline Furth, M.D. -

Toward 21st Century Democracy

— an interview with Steven Hill -

Proportional Representation: The Urgency of Real Reform

— Gerald Meyer -

Can Repression Save Indonesia's Suharto?

— Dianne Feeley -

Congratulations!

— The Editors -

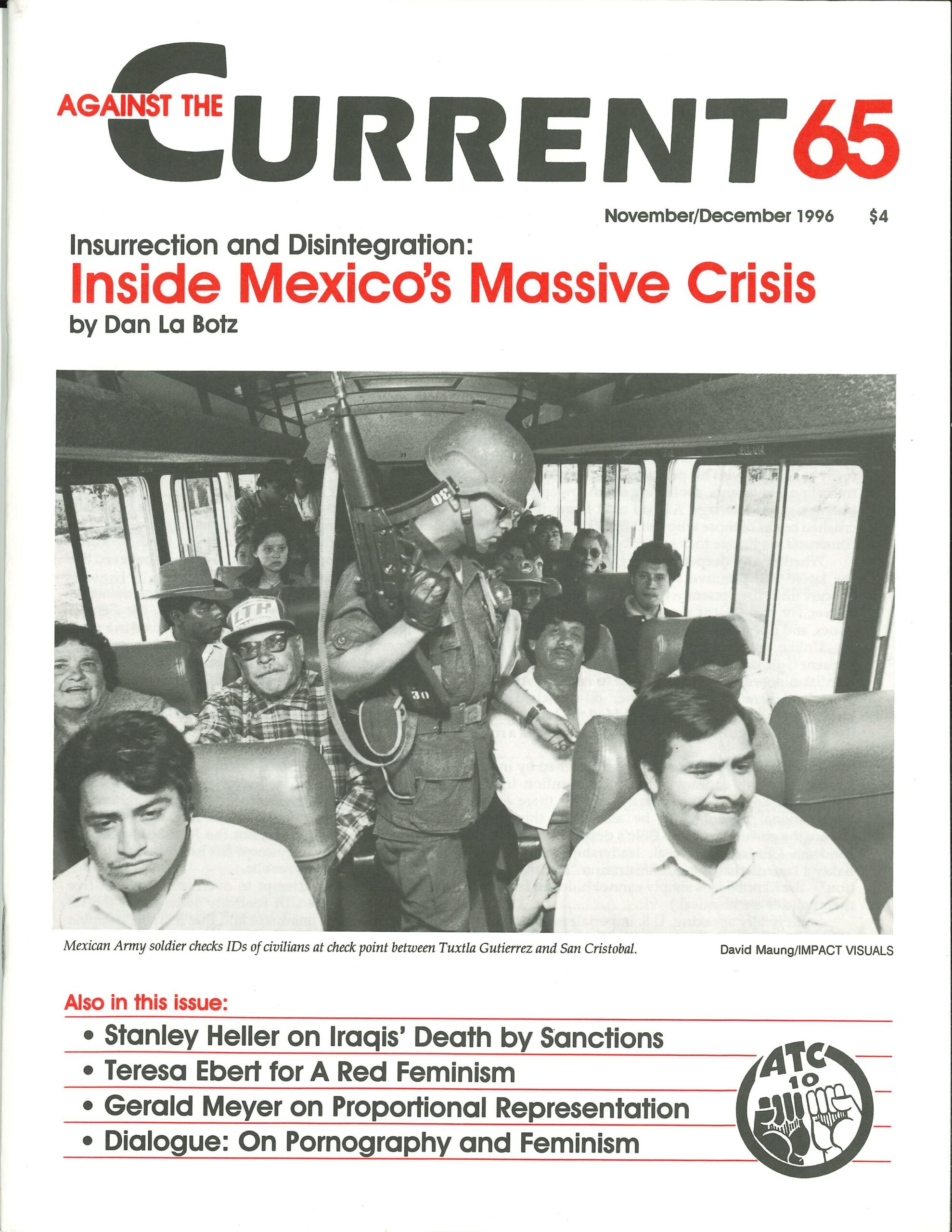

Mexico: Insurrection and Disintegration

— Dan La Botz -

Towards A Red Feminism

— Teresa Ebert -

The Rebel Girl: The Transgendered Outlaw

— Catherine Sameh -

Detroit Newspaper Strike Update

— The Editors -

Random Shots: Notes from a Smoker's Diary

— R.F. Kampfer - Viewpoints on the "Stand for Children"

-

Standing for Children, or Clinton?

— Susan Dorazio -

Standing for All Our Children

— Sasha Roberts - Reviews

-

Marxism and the Fate of the European Jews

— Peter Drucker - Dialogue

-

A Response to Cathy Crosson

— Anne E. Menasche -

A Rejoinder

— Cathy Crosson -

On the Trotskyist Opposition

— Paul Le Blanc -

A Rejoinder

— John Marot - In Memoriam

-

Michel Mill 1944-1996

— Patrick M. Quinn -

In Memory of Constance Coiner

— Alan Wald -

Friend, Scholar and Fighter

— James Petras -

In Memory of Steve Zeluck

— Lew Friedman -

Steve Zeluck: Revolutionary Marxist

— Charlie Post

Paul Le Blanc

I WOULD LIKE to take issue with John Marot’s lengthy polemic (ATC 64) against the final volume of Tony Cliff’s useful Trotsky biography. Most of Marot’s five-page review consists of a critique of “the Trotskyists” in an increasingly Stalinized Russia.

The thrust of Marot’s critique is that Trotsky’s analysis of the nature of the bureaucratic dictatorship made it impossible to mobilize the working class to defeat Stalinism, that it led instead to the Russian Trotskyist leadership embracing Stalin’s “left turn” and capitulating to the totalitarian regime.

Marot concludes that

“Trotsky reaped the bitter fruits of defeat [of revolutionary socialism] in Europe and America insofar as he sowed the seeds of working class defeat in Russia. For the destiny of Trotskyist political tendencies internationally was largely predetermined in Russia . . . Trotsky paid for this defeat with his life. So would millions more.” (ATC 64, September-October 1996, 44)

Of course, modern Trotskyism as we know it–which includes Trotsky’s classic critique of Stalinism in the mid-1930s work “The Revolution Betrayed”–came into being only after Trotsky’s exile in 1929 from the USSR.

Many of the so-called “Trotskyist leaders” of the Left Opposition critiqued by Marot would not have viewed themselves as Trotskyists in this sense. As Marot notes, there were different currents within the Left Opposition, including the ones that broke from Trotsky and capitulated to Stalin–but even those who didn’t can hardly be expected to have had everything figured out to their own satisfaction.

It was by no means a simple thing to figure out all of the complexities of the incredibly fluid situation of Soviet Russia in the 1920s. While Trotsky’s own analysis was still inadequate, and still in flux, little is gained through impatience with historical reality and 20/20 hindsight.

It is important to recognize that, despite ultimately fatal deficiencies and distortions, the Russian Communist Party and the Soviet regime of 1927 were qualitatively different from those of 1937–yet Marot seems to insist that a 1937 analysis should have been in place and guiding the practical political work of the Left Oppositionists by the mid-1920s.

While some (hardly all) Left Oppositionist leaders capitulated to Stalin, for Trotsky “the gulf between Stalinism and the Opposition remained fixed,” as Isaac Deutscher noted almost forty years ago.

“Persecution continued. The party was still robbed of its freedom, and its regime was getting worse and worse. The dogma of the Leader’s infallibility was established; and it was applied to the past as well as to the present. The entire history of the party was falsified to meet the requirements of that dogma. Under such conditions the Opposition could take no step to meet the ruling faction half-way. (The Prophet Unarmed, 418)

This core of revolutionary integrity–essential to the revolutionary Marxism of Trotsky and those who followed him–gave Trotskyism a power and continuing relevance which Marot would have done well to emphasize in his review.

ATC 65, November-December 1996