Against the Current, No. 64, September/October 1996

-

Who Gets To Choose?

— The Editors -

Nicaragua: The Mischief of Senator Helms

— Chuck Kaufman and Lisa Zimmerman -

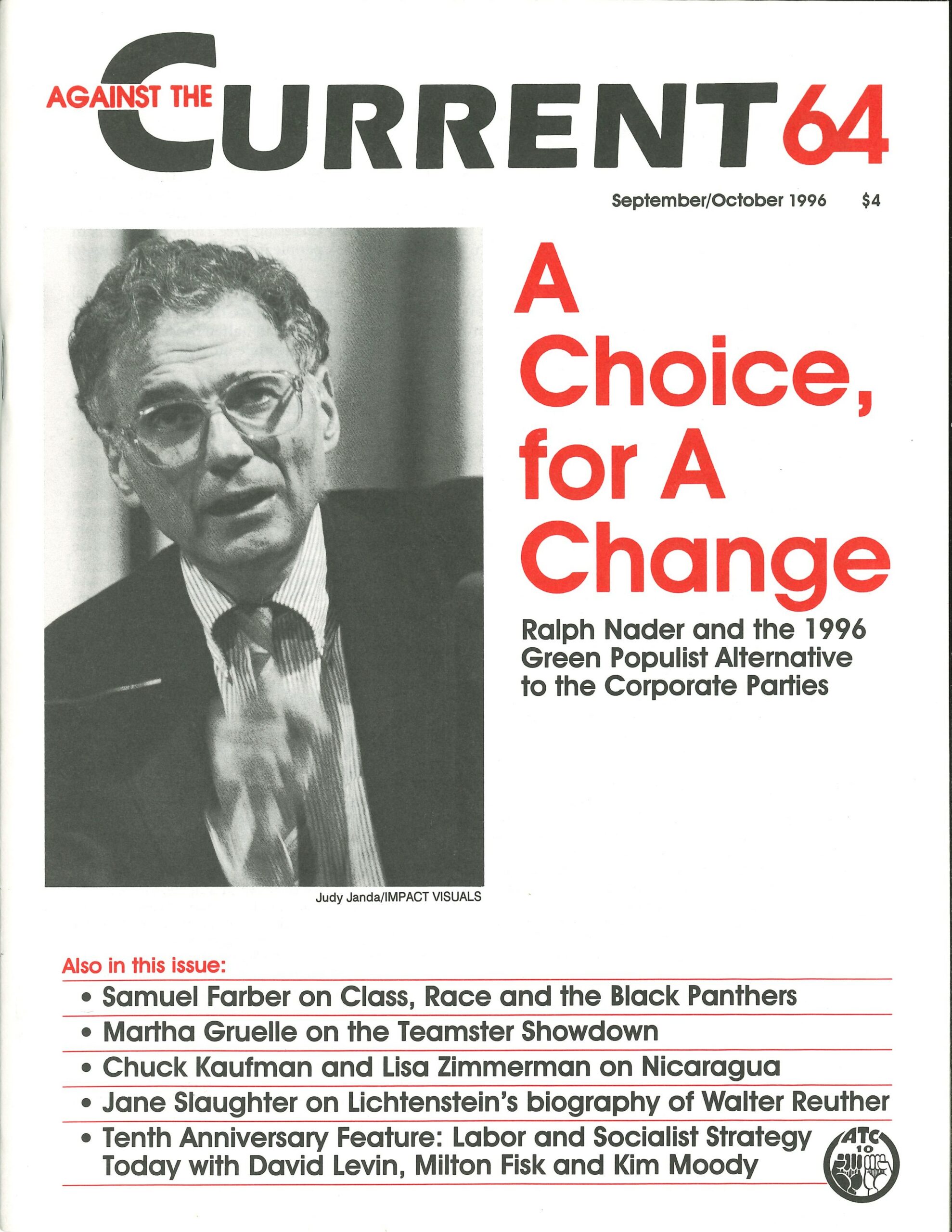

Ralph Nader and the Greens

— Walt Contreras Sheasby -

New Teamsters vs. The Old Guard

— Martha Gruelle -

The End of the Hogan Family Dynasty

— Martha Gruelle -

How Oakland Teachers Fought Back

— Bill Balderston -

The Black Panthers Reconsidered

— Samuel Farber -

The Rebel Girl: Is There Life After Olympics?

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Kampfer's Kreative Krossword

— R.F. Kampfer - Labor and Socialist Strategy

-

New York's Latino Workers Center

— David Levin -

Promoting Unity and Solidarity

— Milton Fisk -

Unity Begins Somewhere

— Kim Moody - Reviews

-

The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit

— Jane Slaughter -

A Note on the Mainstream Reviews

— Jane Slaughter -

From Marx to Gramsci: A Reader

— Lisa Frank -

Always Running, Never A Radical

— Christopher Phelps -

Yugoslavia Dismembered

— Kit Adam Wainer -

Building Working-Cass Opposition to Stalin's Dictatorship?

— John Marot -

Evidence from the Archives

— John Marot

Christopher Phelps

First in His Class

by David Maraniss

New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995, $14 paper.

THE STRANGELY AGITATED and mercurial public mood under the presidency of Bill Clinton derives, curiously enough, not from Clinton’s own attributes (bland and unimpressive in isolation) but from his policies’ failures and the extraordinary depth of hatred for him on the right. Bashing Clinton to a point beyond reason is the cause celebre of Dittoheads and readers of The American Spectator tortured by nightmares of the President as a stealth radical–a draft-dodging, dope-smoking philanderer, using the White House as a base for subversion under the thumb of his domineering feminist wife.

Old habits of paranoia make it easy to understand the right’s irrational response to Clinton. Fantasies of a culturally subversive Clinton play upon old themes of reds under beds, now shot through with lingering resentments about the sixties and fed by the new traumas of long-term social decline.

More dismaying and puzzling is the development of an inverse interpretation on the left, where many still suffer from the inexplicable delusion that Clinton is a closet progressive or, at the very least, an imperfect populist.

To make their case for a left Clinton, each of these camps, aggressive reaction and a weary left–liberalism, must underplay Clinton’s self-description as “neither liberal nor conservative but both and different”–a phrase that, while characteristically Clintonian in its muddle-headed attempt to reconcile opposites, far better explains the ineptness, betrayals, flailing and tailspin of his presidency than any attempt to make him out as a stealth radical or repressed populist.

First in His Class, despite its deceptively adulatory title, cuts far closer to this truth with a simple, revealing account of Clinton’s early life. Washington Post reporter David Maraniss interviewed hundreds of figures close to Clinton–including some associates, like disillusioned aide Betsey Wright, who had never before divulged their stories to any reporter. The resulting biography leaves Clinton’s contradictions in full view.

While Maraniss misleadingly designates Clinton an “activist” because of his love for campaigning, he correctly dispenses with the false “notion that Bill Clinton began his political career as a radical and moved inexorably rightward over the decades.”

Clinton, as the centrist Maraniss is perfectly happy to demonstrate, never had a radical bone in his body. Although First in His Class doesn’t go past the day Clinton announced his bid for the Democratic nomination, Maraniss shows precisely why no one should ever have expected a Clinton administration to be anything more than a faithful delivery service for corporate interests.

The Making of the Politician

Maraniss, to be sure, is not much of a political critic. He writes most vividly when reconstructing Clinton’s personal history. Born William Jefferson Blythe III in 1946 in Hope, Arkansas, to a young widow and nurse, Virginia Dell Blythe, the future president had a childhood replete with afflictions that in his day might have been called “trials” and are now called “dysfunctionality.”

Three months before baby Bill was born, his father drowned in a water-filled ditch, where he had collapsed after crawling from the wreckage of a late night auto accident. In 1950, the young widow Virginia Blythe moved to nearby Hot Springs after marrying Roger Clinton–a Buick dealer who drank heavily, loved to gamble, abused his wife, and rarely spent time with her boy.

One of Maraniss’s few attempts at analysis is his argument that Bill Clinton has a personality type common to households afflicted with alcoholism. Maraniss sees Clinton as the “family hero,” both a protector (who fulfills needed responsibilities) and a redeemer (dispatched into the world to excel, creating vicarious success for the agonized family).

His parents’ marital conflicts, combined with his stepfather’s remoteness and alcoholism, Maraniss argues, gave Clinton his quintessential attributes: a hunger for company and friendship, a powerful drive to succeed, and a disastrous eagerness to make everyone happy.

Even in high school, as girl next door Carolyn Yeldell tells Maraniss, Clinton seemed to “make crowds happen. He had a psychological drive for it, a need for happy and nonconfrontational associations.”

By 1963 he was already a glad handing, energetic opportunist. As a delegate to the American Legion’s high school Boys State, he worked the crowd to get elected senator. That won him a trip to Boys Nation in Washington, D.C., where by lunging ahead of the other boys he was the first to shake the hand of his hero, John Fitzgerald Kennedy. That placed the eager beaver in the center of a White House lawn photo of priceless value for any ambitious Democratic climber.

That’s what “first in his class” means to Maraniss: Clinton, a politico to the core, at the top in shrewdness and acumen. If the phrase inadvertently gives off an air of intellectual brilliance, none is meant. Clinton was smart and able, but elective office, not scholarship, was his aspiration. He was a fine student at Hot Springs High, where he did well without seeming to study much, a pattern replicated throughout his educational career.

He enrolled in Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, which he calculated would place him at the center of national politics in Washington. There he aggressively sought the superficial, symbolic, vacuous posts of student government, campaigning hard to win the presidency of his freshman and sophomore classes.

During his college years, Clinton worked as a summer staffer for an unsuccessful Arkansas gubernatorial candidate and then for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee under Arkansas Senator J. William Fulbright, a segregationist and early dissenter from the Vietnam War.

Though a supporter of Lyndon Johnson, Clinton gradually came to see the war as a mistake. He genuinely admired Martin Luther King. But Clinton was such a smooth operator that the new spirit on the campuses–where political action was increasingly understood as a vital, encompassing aspect of everyday experience, not a career to be pursued at the top–totally eluded him.

Seen as slick, too cosy by half with administrators, he lost the senior class presidential election for which he had groomed himself. More than half of his 1250 Georgetown classmates–a group that had been around Clinton three straight years and knew him very well–voted against him. Maraniss, with classic journalistic understatement, writes that Clinton was “first in his class in terms of political will and skill, and yet people could sometimes tire of him.”

Clinton, full of contradictions, was “considerate and calculating, easygoing and ambitious, mediator and predator.” ;The same student who grated on his classmates was fondly loved by each one of his multiple girlfriends.

“He was writing letters to his first Georgetown girlfriend, Denise Hyland, and to a later Georgetown girlfriend, Ann Markesun,” writes Maraniss. “In Hot Springs, Carolyn Yeldell thought she and Bill had something special going and in Little Rock he was spending considerable time with beauty queen Sharon Ann Evans.” (One of the truly great moments in First in His Class comes when poor, loyal Yeldell, the girl next door, kneels beside her bed, praying. “God,” she asks, “am I supposed to marry Bill Clinton?” “No!” responds the Almighty. “He’ll never be faithful!” God sure called that one right.)

Conservative allegations that Clinton was a youthful radical rely heavily on his late-sixties years at Oxford, where the president-to-be is alleged to have smoked pot, evaded the draft, and traveled to the Soviet Union on a revolutionary pilgrimage. Maraniss shows, in the best sections of the book, that Clinton was a third-rate Rhodes Scholar who was not much of a rebel at all.

Incredibly enough, Clinton really couldn’t inhale. “We spent enormous amounts of time trying to teach him to inhale,” says a British acquaintance, Sara Maitland. “He absolutely could not inhale.” And while a young Christopher Hitchens and the Oxford Revolutionary Socialist Society led rowdy demonstrations against the war, Clinton could be found defending the American political system in impassioned conversations with his classmates.

When Clinton traveled on his own to Moscow, as many Rhodes Scholars did (indeed, they were expected to travel at some point during their European stay), he hung out with a pair of Ross Perot types there to lobby on behalf of P.O.W.s in Vietnam.

Maraniss proves that Clinton opposed the war on moral grounds, but that he was a liberal in all respects. The fullest extent of his activism was during his second year at Oxford, when he organized a few mild protests of Rhodes Scholars outside the American Embassy in London. The events included a candlelight vigil and a prayer service in a church, to which Clinton wore a suit and tie. This, in 1969: the year following the Tet Offensive, the May uprising in Paris, and the Czech suppression!

Pretty tame stuff. Clinton’s maneuvering to get around the draft, intelligently reconstructed by Maraniss, was an admixture of self-interest and agonized conscience, sincerity and lies. This confusion was typical not just of Clinton but of an entire generation caught in a death noose. Clinton later lied about this part of his past. But his distortions didn’t cover up a radical past. They merely obscured his efforts to wriggle free of the draft, something Dan Quayle (that notorious ultraleftist) was also busy doing at the time.

That imperfect, fleeting, mild instant of late-60s dissent was the closest Clinton ever got to the left. From then on, he loped to the right. The record of Clinton’s political career is utterly conventional, only significant for its illustration of the sorry fate of liberalism and the near-total corruption of American politics.

Preparing for Politics

When he returned from Britain, Clinton attended Yale Law School, where he met Hillary Rodham, a former “Goldwater Girl” from Chicago who had turned liberal and would later serve on the House Judiciary Committee staff inquiry into Watergate. He worked as the Democratic state coordinator in Texas during George McGovern’s campaign in 1972.

As McGovern tells Maraniss, Clinton drew from that defeat “the lesson of not being caught too far out on the left on defense, welfare, crime.” Returning to Arkansas, Clinton took a job teaching law at the state university in Fayetteville, where Rodham later became a faculty member, too.

As an aspiring Arkansas pol in the 1970s, Clinton portrayed himself as a son of soil and toil, though he’d never worked in a factory or on a farm.

He publicly stiff-armed the labor movement to show his “New Democrat” colors. He cozied up to Don Tyson, owner of the state’s giant chicken industry. His first gubernatorial term, which eventually met with repudiation from the voters, was doomed, as Maraniss puts it, by Clinton’s “loose, free-wheeling management style, his conflicted personality, and his urge to be all things to all people.” (Only in rare private moments does Clinton show any appreciable guts in First in His Class, as when he calls Bob Dole “the biggest prick in Congress” in a 1976 letter to a friend, and yells “You’re fucking me!” into the phone at a Carter White House official during the Cuban refugee crisis of 1980.)

The weakest chapters of Maraniss’s biography are these final ones, because political analysis is not his strong suit. By concentrating upon issues of character, Maraniss tends to treat politics as little more than a popularity contest. He fails to understand the historical significance of Clinton’s particular form of corporate liberalism and the drive he led to damage the position of the labor bureaucracy within the Democratic Party.

First in His Class, that is, takes “class” to be a ranking based upon personal quality, not a social category. Given his own mundane political perspective, Maraniss cannot see that Clinton’s weaknesses are not merely moral and are not his alone, that what seem personal failures are equally the failures of a party that has lost any purpose or vision except to serve corporate interests a shade differently than the Republicans while making hollow election-season gestures toward populism.

ATC 64, September-October 1996