Against the Current, No. 63, July/August 1996

-

Israel's Poisoned Fruits of Oslo

— The Editors -

Founding the Labor Party

— Dan La Botz -

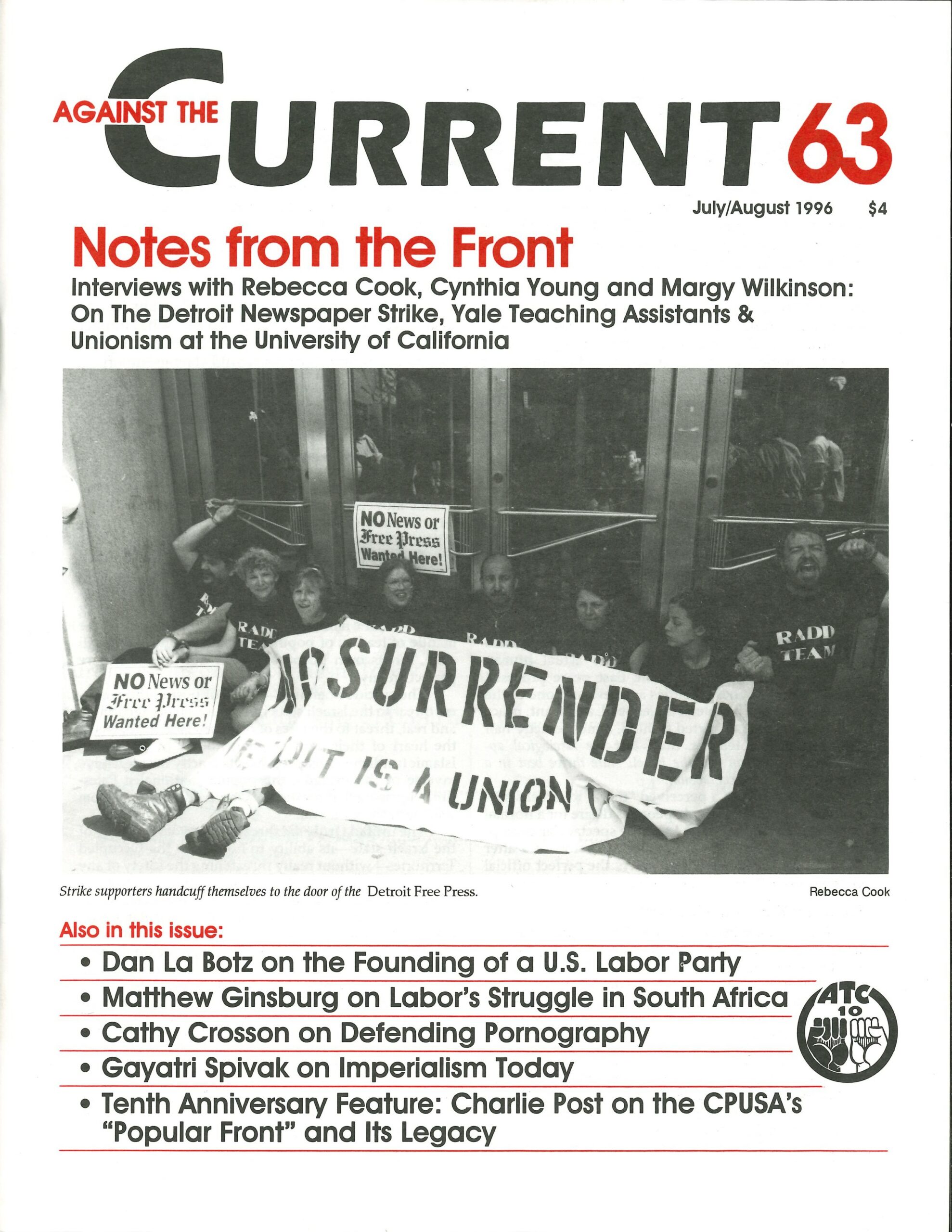

Detroit Newspaper Unions' Year of War

— interview with Rebecca Cook -

The Yale Grad Student Strike

— an interview with Cynthia Young -

A New Campus Union at University of California

— Claudia Horning interviews Margy Wilkinson -

The "Team Bill," A Poison Bill

— Ellis Boal -

Class and the African-American Leadership Crisis

— Malik Miah -

South African Labor Marching Again

— Mathew Ginsburg -

More on "Imperialism Today"

— Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak -

The Comintern, CPUSA & Activities of Rank-and-File CPers

— Charlie Post -

The Popular Front: Rethinking CPUSA History

— Charlie Post -

Queer Vows, Pros and Cons

— Catherine Sameh -

Radical Rhythms: "Global Divas"

— Kim Hunter -

Letter to the Editors

— Paul LeBlanc -

Random Shots: Wages and Other Minima

— R.F. Kampfer - Reviews

-

Pornography and the Sex Censor

— Cathy Crosson -

Reading Red Women Writers

— Renny Christopher -

The Uses of Dmitri Volkogonov

— Samuel Farber -

Trotsky Assassinated Again

— Susan Weissman

Ellis Boal

BEFORE DECIDING TO quit the U.S. Senate in May, Republican leader Bob Dole thrust an obscure labor bill into the forefront of political discourse. President Clinton called it a “poison pill” in the budget package and promised a veto. It’s called the “Team Bill.” What’s it all about?

The Teamwork for Employees and Managers Act of 1995 (H.R.743/S.295) passed the House last fall, and passed the Senate labor committee on a party-line vote in April. It would amend the National Labor Relations Act (NLRB) so that a company may set up and dominate employee “teams.” The authors claim the bill would give workers a collective voice on the shop floor and encourage ideas about productivity and working conditions.

Labor law already allows this: workers have to decide democratically whether they want a team or not. If they say “yes,” the employer cannot dominate it. The common name for such a team is “union.” And if workers say “no,” companies can still deal with workers individually.

The bill’s preamble claims that their are at least 30,000 teams already operating. If so, workers can easily get rid of them by filing a cost-free charge at the National Labor Relations Board because they are illegally constituted.

The NLRB legislation was enacted in the 1930s to outlaw phony “company” unions. These enjoyed a heyday in the decade of the 1920s, attempting to pre-empt the possibilities of militant unionism. The law worked so effectively that after the first few years, companies stopped trying. The Supreme Court has ruled on Sections 2(5) and 8(a)(2) of the NLRB fourteen times. Amazingly, it found the companies guilty every time — unanimously.

Today companies say foreign competition is pressing American business and management needs help from the workforce. Besides, they say, cooperation is really more democratic because it gives workers a voice in management.

In 1992, employers tried to overturn the prohibition against company unions in the celebrated Electromation test case. They filed 403 pages of briefs and exhibits, claiming the law hinders cooperation and productivity. Ten right-wing congresspeople asked the NLRB to overrule its precedents in light of “shifts with the fortunes of the political parties.”

But the NLRB ruled against the company, whose “action committees” had been set up to deflect worker discontent. After the committees’ were disbanded, the workers successfully organized themselves into a Teamsters local and signed a three-year contract with the company. So the story has a happy ending.

The teams in Electromation had nothing to do with productivity. They dealt with classical bargaining subjects like attendance bonuses. So why would employers choose that case to make their pitch? The answer: They think they can get away with anything.

The Dunlop Commission

President Clinton’s Commission on the Future of Worker-Management Relations, known as the Dunlop Commission for its chairman John Dunlop, was set up in 1993 to recommend new labor legislation in the light of current labor-management practices. The focus was on cooperation, teamwork, quality circles in order to increase productivity.

But the commission had difficulty linking productivity to the existence of employee participation plans. It downplayed in many of the Kelley’s and Bennett Harris’ monumental study of 1,015 metalworking plants where joint committees are in place. Why? Because it found in nonunion plants, operations with joint committees are one-third less efficient than those without.

In searching high and low, the Dunlop Commission found productivity linked to employee participation programs in only three objective studies. All showed positive productivity, but they occurred in unionized plants or where employment security existed.

* In a unionized Xerox plant where the workers had a no-layoffs guarantee.

* A survey of auto plants in seventeen countries concluded that a commitment to employment security or an absolute “no-layoff” policy is probably essential for lean production to take hold.

* A survey of fifteen human resource practices in the steel industry found that firms with the highest performances all operate at suburban or small-town sites and are unionized.

But a number of abhorrent practices were noted in plants and industries. First, the commission took an in-depth look at Toyota’s non-union plant in Tennessee. Testimony showed production relied on circles of youth, healthy, well-educated, male, white, eager and enthusiastic workers. Here workers joined in job elimination. Even managers admitted there was a difference between a democratic, unionized workplace culture and Toyota’s culture.

They also looked at the cooperative NUMMI plant in Fremont, California. Here the workers are represented by the UAW. But when the UAW called a strike in 1994, management called on workers to resign from the union and cross the picket line. Cooperation seemed to fly out the window.

In order to produce positive peer pressure, one study cited by the Dunlop Commission promoted “shame” and “guilt.” It also recommended “weeding out” or “converting” workers who do not respond to the pressure.

The Commission did propose weakening workers’ existing protection against company-dominated worker organizations by “clarifying” Section 8(a)(2) of the National Labor Relations Act. The Commission would allow employers to form teams that discuss conditions of work or pay, if those discussions are “incidental to the broad purposes” of the group. The Commission, attempting to mediate disputed issues in a consensus mode, hoped to sell a compromise: some minor tinkering of labor law to make it easier for workers to join unions and win contracts in exchange for employer-dominated quality circles in which pay and work rules come up “incidentally.”

Neither labor nor management was happy. The corporations wanted company-run employer groups endorsed straight out while the lone labor representative on the commission, retired UAW President Doug Fraser, wrote a dissenting opinion. He stated that labor-management cooperation had to take place where workers have “an independent voice” — presumably a union.

But the Dunlop Commission was only proposing to weaken 8(a)(2) in

relation to unionized workplaces, it would still be illegal to set up a company union in a non-union facility. However the Team bill takes the employer-dominated ball and runs with it. If employer/worker teams are good enough for union plants, then under the team act they are good enough for every worksite.

The Global Economy

The posturing about competitiveness and world-wide markets has a downside. It leads workers to think in terms of their company, not their class. But workers have interests and allies far beyond their own plant. Last summer the court of appeals in Washington held that in a labor dispute a U.S. union could not be liable for the acts of a Japanese union acting solely out of solidarity with the Americans.

It is not just management that wants to change the law. Liberals have jumped on board too. In the name of productivity and cooperation, NLRB chair William Gould, Professor Charles Morris, Representative Tom Sawyer (Ohio-D), and even some unions have made proposals. The proposals do preserve specified democratic elements. But they lengthen and bureaucratize the law with a barrage of exceptions and counter-exceptions impossible for ordinary people — not to mention judges — to understand.

If workers aren’t filing NLRB charges, one wonders why management is so worried. Historically management has tried only for incremental incursions on labor protections. But it has never challenged ideologically labor’s right to exist independently. Since the passage of the NLRB action management has not legally challenged labor’s basic rights.

The Team Bill is a dagger pointed at the heart of workplace democracy. Employer-dominated teams give employees the same voice a ventriloquist does. Dummies may be cute — but they are not of flesh and blood and they have no brains.

ATC 63, July-August 1996