Against the Current, No. 62, May/June 1996

-

Ten Years of Against the Current

— The Editors -

How Labor Loses When it "Wins"

— Peter Downs -

Yale Workers Fight the Power

— Gordon Lafer -

Brazil's Workers Party Redefining Itself

— Michael Shellenberger -

Modern "Gunboat" Diplomacy in the Caribbean

— an interview with Cecilia Green -

"Burn the Haystack!"

— News From Within -

The Clinton-Helms-Burton Travesty

— The ATC Editors -

The IMF Restructures Sri Lanka

— D.A. Jawardana -

Chandrika's "Great Victory"

— Vickramabahu Karunarathne -

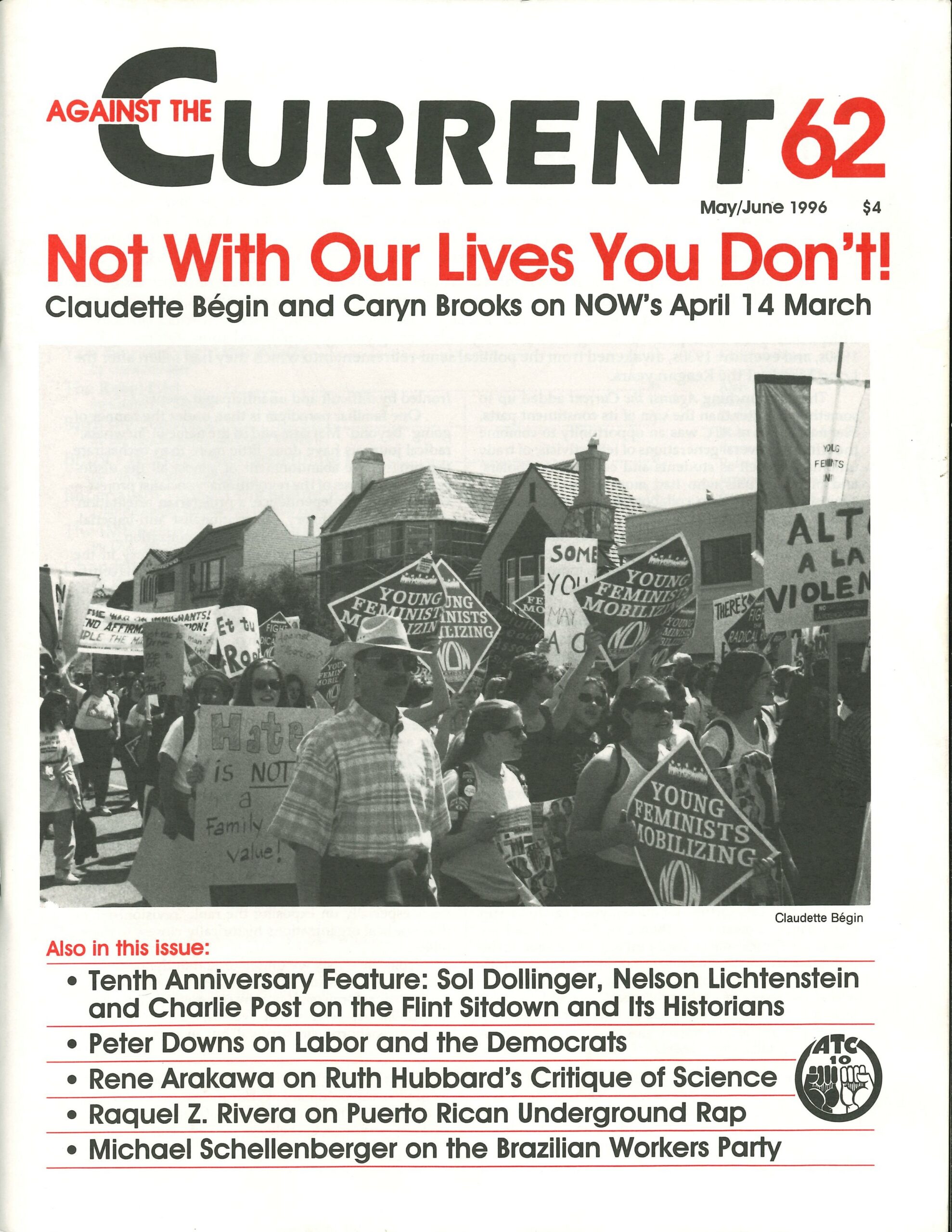

Getting It Right About Now

— Claudette Begin and Caryn Brooks -

Fight the Right

— Claudette Begin -

Ruth Hubbard's Feminist Critique of Science

— Rene L. Arakawa -

Reclaiming Utopia: The Legacy of Ernst Bloch

— Tim Dayton -

Policing Morality: Underground Rap in Puerto Rico

— Raquel Z. Rivera -

Answering Camille Paglia

— Nora Ruth Roberts -

On Being Ten

— Greetings from Our Friends -

Letters to the Editors

— Peter Drucker; Linda Gordon - The Great Flint Sitdown: An ATC 10th Anniversary Feature

-

Introduction: The Flint Sitdown for Beginners

— Charlie Post -

The Rebel Girl: The Real Threat to Life

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Politics, Religion and Mad Cows

— R.F. Kampfer -

Flint and the Rewriting of History

— Sol Dollinger -

Politics and Memory in the Flint Sitdown Strikes

— Nelson Lichtenstein - Reviews

-

McNamara's Vietnam

— Lillian S. Robinson -

Ken Saro-Wiwa's Antiwar Masterpiece

— Dianne Feeley -

Statement to the Court

— Ken Saro-Wiwa - In Memoriam

-

Marxist Art Historian: Meyer Schapiro, 1904-1996

— Alan Wallach

D.A. Jawardana

SRI LANK IS a beautiful island in the Indian Ocean consisting of 25,000 square miles, with a population of 18 million. Some call it the pearl of the Indian Ocean. Today the people of my country are being threatened by the policies of the World Bank and the IMF. These policies have, since the 1970s, brought disaster to Sri Lanka — and also to many other Third World countries.

There are different ethnic groups in Sri Lanka. The Sinhalese-speaking population is the majority, Tamils and Muslims are the minorities.

The economy of Sri Lanka is predominantly agricultural. About 70% of the labor force are farmers, mostly subsistence farmers who grow food for their own consumption. The major cash crops in the past were tea, coconuts and rubber. And many non-agricultural workers were engaged in processing these agricultural products.

Since 1977 major economic changes have been introduced; the entire country has been turned into a free trade zone. This has resulted in the introduction of new cash crops profitable for multinational corporations, such as tobacco and small cucumbers for gherkin pickles. It has also turned more people into poorly paid factory workers. About 15% of the labor force are producing garments, shoes and plastics, as well as working in plants where workers assemble men’s razors, ballpoint pens, batteries and automobiles. The majority of this workforce is female.

The Political Spectrum

From 1815-1948 Sri Lanka was a British colony. Since independence the government has been a parliamentary system. There are a number of political parties, but the two biggest are the United National Party (UNP) and the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP). Both embrace capitalist economic development. The UNP is a right-wing party while the SLFP has a history of favoring social reforms.

The parties of the left include the Communist Party (CP), the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP — Lanka Equality Party), the Nama Sama Samaja Party (NSSP — the New Equality Party) and the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuma (JVP — Peoples Liberation Front). Begun by young militants in the 1960s, the JVP first engaged in guerrilla warfare and was violent toward other left-wing parties. But since the late 1980s it has participated in elections. The combined weight of these four left parties equals the size of each of the larger parties.

In addition, there are important three political organizations. One is the Mahajana Eksath Peramuma (MEP — Peoples United Federation), which is a Sinhalese Buddhist organization that favors racist policies against the Tamil and Muslim minorities. The second is the Muslim Congress, which wants to establish a Muslim government on the east coast of Sri Lanka, where there are high concentrations of Muslims. And finally there are the Tamil Tigers. This group does not participate in elections, but engages in guerrilla warfare and terrorist activities in order to create a separate government for the Tamil minority.

My own party is the NSSP. We are socialists, which means we are for the majority of people taking hold of the economy for the benefit of those who labor — the workers and farmers and poor. We follow the ideas of Marx, Lenin and Trotsky. The NSSP is an offspring of the old Lanka Sama Samaja Party, which was once a revolutionary socialist party. In the 1960s and ’70s it became a more moderate, reformist party, when it joined with the capitalist parties at the expense of revolutionary principles.

We organized the NSSP in 1977 in opposition to the LSSP’s coalition tactics. The LSSP joined with the capitalist parties at the expense of revolutionary principles. Today we have about 3,000 members, mostly laborers. Peasants, youth, women and students are also members. Several union leaders and leaders of mass social movements also belong.

In 1980 we organized a general strike because of the sharply rising cost of living. At that time the UNP government rejected the demands for wage and salary increases and thousands were fired. Some workers committed suicide because they could not feed their families. In 1983 our party was suppressed by the government and we were forced to work underground for nearly two years.

In 1988, because of a change in the country’s constitution, several provincial councils were established. We formed an election front, the United Socialist Alliance, with the LSSP, the CP and the SLMP, a left-wing split-off from the SLFP that abstained from the elections). The Alliance, leaded by former President Chandrika Bandaranayaka Kumarathunga, became the primary opposition to the UNP government. Several provincial council candidates, including members of my party, were assassinated by the JVP and Tamil Tigers but five NSSP members were elected, including myself.

During the election campaign the government offered weapons to the NSSP, to use against those who were trying to kill us. They hoped we would become involved — along with the police and the army — in helping to kill these rebellious young people driven to violent tactics.

But while we took measures to protect our comrades, we refused to participate in the government’s campaign. We recognize that many of the young people drawn to the JVP will be important to the future of the country. Instead of trying to kill them, we worked to save their lives from the government forces. We also worked with Amnesty International and others to stop human rights abuses, which included the disappearance of 60,000 young people. We helped build the Organization of Parents and Family Members of the Disappeared.

Opening the Economy

The UNP was in power from 1977 until November 1994. During that period it carried out “the open economic policy.” This policy is a structural adjustment program whereby corporations impose requirements upon the government in order for it receive IMF or World Bank loans. The policies require severe cutbacks in public spending for health, education, welfare and other social services as well as the privatization of nationally controlled sectors of the economy. Through structural adjustment a favorable investment climate is established. This opens the country’s national borders to penetration by foreign companies and products. It also imposes severe conditions upon the local work force, including the lowering of wages.

As a result of the “open economic policy”, state-owned properties have been sold to the private sector at bargain prices. State-owned corporations in steel, tires, graphite and lead are now in private hands.

Before 1977 people had many social benefits, but these have been pushed back by the new policies. Schools and health care have declined, as well as our transportation system. The cuts have affected not only services but also led to a deterioration of the infrastructure and equipment.

Because rice farming does not fit in with the plans of the multinational corporations, the government also cut subsidies to rice farmers. Instead rice — our principal food — is being imported and farmers are being pressured to grow cash crops for export. Companies sell to the farmers — on credit — seeds and fertilizer, as well as insecticides and weedicides. This harms the environment and destroys the soil. The farmers then sell their crops back to these corporations. But after awhile, with the accumulation of debt and the depletion of the soil, the lower crop yields makes the farmer’s situation desperate. In Polonnaruwa District, for example, there are twenty-two farmers who have committed suicide over their debts.

The government talked about how its policies were designed to create economic development. But what development have we seen? Income differences have widened. Unemployed has risen. Per capita income has been falling while the cost of living has gone up. According to the Central Bank report, sixty percent of the children under fifteen are undernourished. Ten percent of our babies don’t weigh enough and their mothers are anemic. Malaria is increasing in rural areas. Many infants in my district of Kurunegala suffer from thelecemia, a blood disorder that can be traced to the undernourishment of the parents. This is happening in other districts too.

Because of these disasters, we have demanded that the government give up their “open economy” system. We have prepared a People’s Memorandum, outlining our problems. We asked people to sign its call and about 200,000 signatures were collected among farmers. We have helped to build a mass peasant organization, the Movement of the National Lands and Agriculture Reform. Last January 17 we had a demonstration with thousands of people in Colombo, and two days later we handed the memorandum over to the new president.

In 1994 the UNP was defeated by a Peoples Alliance, a coalition comprised of the SLFP, the CP, the LSSP and the SLMP. The new government, led by President Chandrika of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party, has also pledged to maintain the same “open economic system.” Although this government is not as right wing as the UNP, it too favors capitalist economic development. For that reason, my party did not support Chandrika and the Peoples Alliance, but we think the government may be more sensitive to pressures from progressive forces.

For that reason, we demand that the present government solve the problem of the disappeared and take legal measures against the police and army. The fight to end human rights abuses is central to our campaign.

Additionally, we want to mobilize popular pressure against the World Bank policies. We are arranging a mobile exhibit to educate people throughout the country about the impact of the World Bank on their lives. We intend to draw together trade unions, farmers organizations and mass organizations. We recognize the need to reach out to people in other Third World countries, and to people throughout the world. I hope that you will join in helping to create such an awareness — structural adjustment is the source of our impoverishment.

ATC 62, May-June 1996