Against the Current, No. 58, September/October 1995

-

Save Mumia Abu-Jamal

— The Editors -

The Right's New Dynamism

— Christopher Phelps -

The Pseudo-Science: Creationism

— Christopher Phelps -

The Gulf War Syndrome Mystery

— Pauline Furth, M.D. -

Britain: Conservatives Collapse & Labor Lurches Right

— Harry Brighouse -

Can Bosnia Resist?

— Attila Hoare -

Radical Rhythms: "Dancing on John Wayne's Head"

— John Greenbaum -

Rebel Girl: Murder, the Double Standard

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Kampfer, Eat Like Him

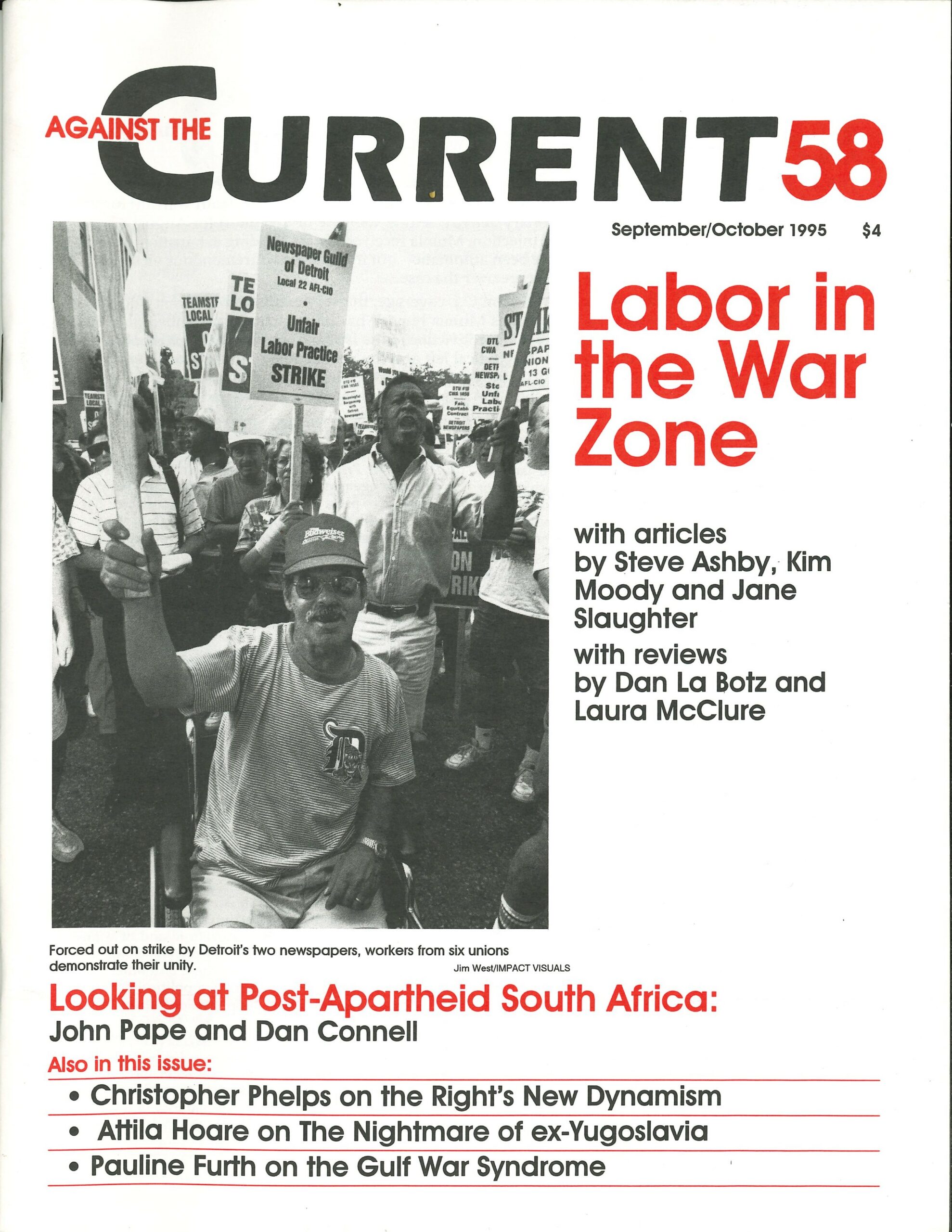

— R.F. Kampfer - Labor in the War Zone

-

June 25th in Decatur

— Steve Ashby -

Staley Workers Vote to Fight On

— Steve Ashby -

Why the Industrial Working Class Still Matters

— Kim Moody -

The New American Workplace

— Jane Slaughter -

Review: Working Smart

— Laura McClure -

Review: The CIO 1935-1955

— Dan La Botz - Post Apartheid South Africa

-

A Note of Introduction

— The Editors -

Year One of the Transition

— John Pape -

What's Left of the Grassroots Left?

— Dan Connell - Reviews

-

Serbia's Flawed Liberal Opposition

— Attila Hoare - Dialogue on American Trotskyism

-

A Reply to Alan Wald

— Steve Bloom -

Our Legacy: A Reply to Critics

— Alan Wald - Letters to Against the Current

-

On "Closing the Courthouse Doors"

— Barbara Zeluck

Harry Brighouse

BRITISH PRIME MINISTER John Major’s decision to resign as leader of the Conservative Party and stand in the consequent contest was no great surprise. Certain that a challenge to his leadership would otherwise come at the autumn party conference he sought to pre empt it and fight at a time of his own choosing.

His victory, though not as decisive as he would have liked, probably represents the best chance that the Conservatives had of winning the next British election. His challenger, John Redwood, a right wing mastermind of the Thatcher privatization programs of the 1980’s, won just 89 votes.

This figure represents roughly the number of Conservative MPs who are thought to be seriously resistant to Britain’s participation in the integration of the European Union. Major owes his victory to Redwood’s inability to command wider support, and to the calculation of pro European MPs that Major, though worse than the Europhile Michael Heseltine (who, under the party’s bizarre election rules, would have entered, and almost certainly won, the race had Major failed to get a sufficient supermajority in the first round), has a better chance of keeping some semblance of unity in the party.

The parliamentary party itself remains deeply divided over Europe and, to a lesser extent, over economic policy. Major has appeared weak, vacillating between pacifying and punishing the recalcitrant Europhobic right wing of his party (which is actually much weaker in the constituencies than in parliament).

Major’s re affirmation as leader will allow him to bully and possibly silence his enemies in the party: they have “put up” and now have to “shut up” in Major’s charming phrase.

But the party also seems riddled with corruption. Last year two junior ministers resigned after revelations that they had accepted money for planting questions in the House, and earlier this year a more senior minister was exposed as having assisted companies to break the arms embargo on Iraq and Iran; several government ministers may have to resign over this affair. The sex scandals have come thick and fast, with an average of one Tory MP having his private life made public every two or three months.

So, although their best chance of success, Major does not give the Conservatives a very good chance. The leadership election was made inevitable by the disastrous local election results on May 4th. Labour achieved forty-six percent of the vote and a net gain of 1,799 seats, winning a total of 5,616, although they have never before made a net gain of as many as a thousand. Labour took control of 44 new local councils, bringing the number of councils under their control to a total of 155.

The slide of the Conservatives was even more startling than Labour’s success. They lost almost half the 4,000 seats they were defending, and lost control of 61 of their 69 councils. The Liberal Democratic party, which now has 2,702 seats, and controls a remarkable 44 councils, has replaced them as the second party of local government.

If the May results were replicated in a national election, the Conservatives would slump from their current controlling majority of 333 to fewer than 140 parliamentary seats, and Labour would win a comfortable majority. The prospect of a “Canadian Scenario” in which the Tories would be wiped out at the national level is much discussed even by the almost solidly Tory press.

Major’s victory does nothing to allay the widespread public distrust of the government’s handling of the National Health Service, which has just provoked the Nurse’s professional association, the Royal College of Nurses, to renounce (by a ninety percent majority) its eighty year long commitment not to take strike action; anger over the high salaries paid to the CEO’s of newly privatized public utilities; or a generalized sense, like that in the United States, that the economic recovery is long on statistics and short on prosperity.

How encouraged should the left be about the Tories’ difficulties? It is not so clear. The Tories are victims of their own success. In sixteen years they have carried out the most successful denationalization program in the world, and demobilized the Trades Unions as well as massively diminishing their ability to serve as a locus of political opposition.

These are lasting successes, which will long outlive a Tory regime. Furthermore, the spring Tory losses were actually less serious than was suggested by pre election opinion poll data. The turnout was unusually low, even for local elections, at something less than forty percent. Many Tory voters simply stayed at home in protest -most of them will turn out, however reluctantly, to vote for their party again in a general election.

It is still very likely that Labour will either win the next election outright or at least lead a government. But is the Labour Party still a party of the left?

The spring elections occurred the week after the much publicized special conference on Clause Four, the “aims” clause of Labour’s constitution, section 4 of which committed the party to “secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof.” It has long been a target of the right wing of the party, and at the special conference the new leader, Tony Blair, proposed and won its revocation in favor of a new and much watered down version, which talks of the value of community and the social need for the “enterprise of the market and the rigors of competition.”

Only three of the 535 constituency parties and some of the largest Trades Unions opposed the change: and all the unions which polled their membership on the question revealed overwhelming support among activists in the ranks for the new clause.

The party lacks clear policies, and its spokespeople consistently deny that they will raise progressive taxation when they win power. By contrast, the Liberal Democratic Party, usually thought of as the center party, has a standing commitment to raise income tax significantly on the highest income brackets.

Allan Beith, deputy leader of the LDP, recently explained that his party was going to have to abandon its previous position of “equidistance” between Labour and the Conservatives because “The Tories are lurching all over the place, and Labour is moving so rapidly to the right that we have no idea what the equidistant point might be.”

The success of the Liberal Democrats in the South of Britain, and the increasing, though still spotty, use of tactical voting for whichever party is most likely to beat the Tory candidate, means that a hung parliament (in which neither party has an overall majority) is a real possibility at the next election. The abandonment of “equidistance” means that the LDP would probably be willing to form a coalition, or at least a working arrangement with Labour.

The big question is: will the new leadership succeed in pushing Labour so far to the right that by that time it will be the center party, leaving the LDP, by no standards a harbinger of radicalism, as the more left wing partner?

ATC 58, September-October 1995