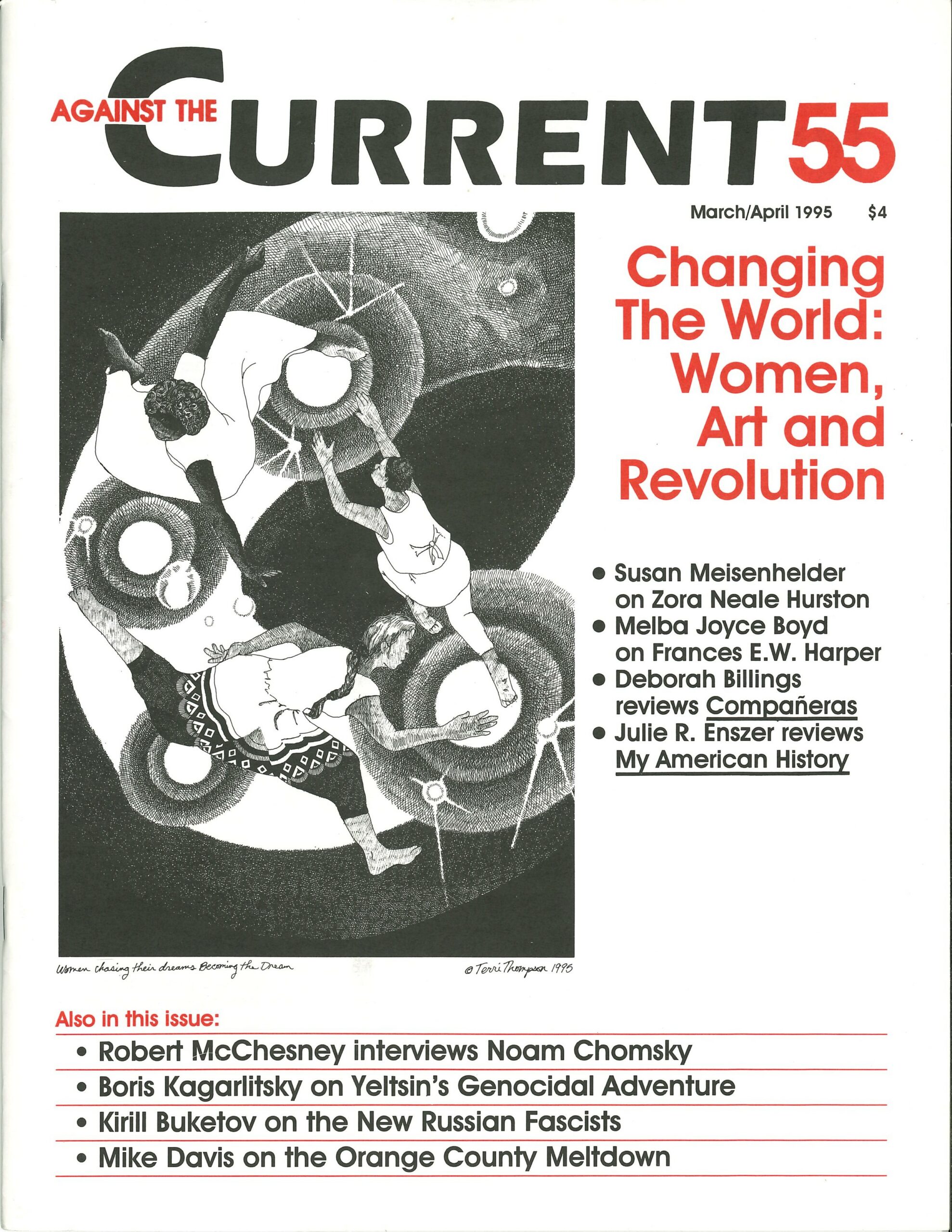

Against the Current, No. 55, March/April 1995

-

Defending Women's Lives

— The Editors -

Resisting Proposition 187

— an interview with Angel Cervantes -

Orange County: Who Pays the Price?

— Mike Davis -

Media, Politics and the Left

— Robert McChesney interviews Noam Chomsky -

Yeltsin's War of Genocide

— Boris Kagarlitsky -

Russia's New and Old System

— John Marot interviews Boris Kagarlitsky -

Russia's New Fascists

— Kirill Buketov -

Brazil After the Elections

— Antonio Martins -

Problems in History & Theory: The End of "American Trotskyism"? -- Part 3

— Alan Wald -

Radical Rhythms: Jazz Currents in Conflict

— Kim Hunter -

The Rebel Girl: Breast Cancer -- No Accident?

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Politically (Un)Kosher Recipes

— R.F. Kampfer - For International Women's Day

-

Gender, Race & Class in Zora Neale Hurston's Politics

— Susan Meisenhelder -

Frances E.W. Harper & the Evolution of Radical Culture

— Melba Joyce Boyd -

Bury Me in A Free Land

— Frances E.W. Harper -

Aunt Chloe's Politics

— Frances E.W. Harper -

A Double Standard

— Frances E.W. Harper -

Speaking Out for Themselves

— Deborah Billings -

Lesbian & Gay Activism During the Reagan/Bush Era

— Julie R. Enszer - Letters to Against the Current

-

On the UAW: Death of a Union?

— Peter Downs -

On Dislando

— J. Quinn Brisben -

Small Inaccuracies on Trotskyism Series

— Frank Fried -

Broadcast Reform

— Eric Hamell - Dialogue

-

IQ, Genes, Race, American Society

— Steve Bloom - In Memoriam

-

Remembering Jerry Rubin

— Robert Fitch

Alan Wald

This is the last part of Alan Wald’s article, the earlier parts of which appeared in ATC 53 and 54. The essay, based on a presentation given to the 1993 summer school of Solidarity, will appear in a volume co-authored by Alan Wald, Paul Le Blanc and George Breitman, Trotskyism in the United States: Historical Essays and Reconsiderations, to be published in 1995 by Humanities Press.

III. Method and Political Action

THERE ARE METHODOLOGICAL aspects of Trotskyism that the twenty-five years since the height of “The Sixties” have shown to be still necessary and valid.

To be precise: In the 1960s there was at the outset a salutary repudiation among New Left activists of both a pro-Stalinism that had illusions about the USSR, and the so-called anti-Stalinist left that saw imperialism (euphemistically labeled “The Free World”) as the lesser evil to “Red Totalitarianism.” But this trend of thinking in the New Left was not based on the Trotskyist method of starting from the objective interests of the working class, regardless of the class’ alleged relation to the state or any party ruling in its name.

This superficial rejection of Soviet Stalinism actually led many to a worship of Maoism, uncritical Castroism, and other trends that later brought sharp disillusionment and great losses. Trotskyism in the 1990s could contribute to correcting this error in regard to future revolutionary developments in the Third World. Some socialist activists from the Trotskyist tradition have already set a good example through their approaches to the Nicaraguan Revolution and the El Salvadoran struggle, and they may possibly make other contributions if they treat in a non-dogmatic way the unfolding crises in South Africa, Haiti and elsewhere.(1)

Still, so far as the U.S. is concerned, Trotskyism must be rejected as an autarkic revolutionary movement, projecting its own hegemonic leadership, even with lip-service to routine (although necessary) expressions such as, “of course, we don’t have all the answers” (which usually means that we think we have most of them). Trotskyism in the United States has been proven too often to be an insufficient worldview, leading mainly to smug little groups that are more like extended families, splitting apart in bitter family quarrels.(2)

A diverse and flexible revolutionary socialist group is quite an anomaly in the history of the U.S. left in general and Trotskyism in particular. In fact, it is precisely this kind of group that the majority of self-proclaimed Trotskyists hate (as “soft,” a “swamp”), define themselves against, and want to see destroyed in order to justify their own vanguardist existence.

If one’s objective is to achieve a socialist movement with authority based on real analytical cogency and power expressive of working-class agency, the pantheon of Trotskyist thinkers and “Great Moments in Trotskyism” must not stand alone. Despite the extraordinary talents and contributions at various times of Cannon, Shachtman, Dobbs, Draper and C.L.R. James, no Trotskyist leaders can credibly be seen as “the” guiding lights of organizational strategy, political theory and philosophy. On the other hand, within a broader context, many of the historic Trotskyist cadres can be appreciated as vital, stimulating and serious contributors.

This issue is somewhat related to the famous charge of “Trotskyist sectarianism,” a charge levelled frequently at Trotskyism by its various critics, although just as frequently by some Trotskyists against others. The charge is difficult to evaluate because, as my preceding analysis would indicate, I think there is considerable truth to it, but opinions vary markedly as to where the borders of sectarian behavior lie.

From my experience, liberals and social democrats are quite capable of sectarian behavior equal to that of revolutionary Marxists, Dissent magazine being a good example in its hostile attitude and unfair caricaturing of almost everything to its left. Moreover, it is possible to present very sectarian politics in a non-sectarian manner,(3) and non-sectarian views shrilly and aggressively.(4)

Nevertheless, Trotskyism has appeared to many to be a politics largely devoted to criticizing the Communist and social-democratic traditions for “betrayal,” which seems a rather preposterous if not counterproductive stance — not because Stalinism is what many activists want, but rather because of Trotskyism’s own comparatively poor showing in terms of practical achievements.(5) Moreover, a turn from the dogmas of Stalinism to the various theories of state capitalism, degenerated workers’ statism and bureaucratic collectivism is unlikely to be the dominant trend we will see among the new generation of socialist activists.(6)

In truth, while the more sectarian Trotskyists get attention (including, sometimes, greater media notice due to their propensity to differentiate themselves from the rest of the Left), there are many other Trotskyists who work wholeheartedly for reform as a way of raising political consciousness and strengthening the positions of the oppressed. But this seems insincere to many independent radicals because most Trotskyists regard only a tiny number of people — usually their group and affiliated organizations, and certain select movements from the past — as genuinely “revolutionary.”

To be genuinely “revolutionary”(7) (in this highly specialized sense) means to adhere to particular policies (not just statements on paper, but interpretations of such statements), although the term “revolutionaries in action” is sometimes used for individuals who, without full political consciousness, nevertheless take action that is compatible with the theory. This latter label, however, seems to apply only so long as someone is committing certain positive acts, and can quickly be rescinded when the actions are interpreted differently.

In any event, it is a dubious schema to regard someone selling a revolutionary newspaper at Columbia University or collecting membership dues in a downtown Los Angeles party headquarters as a bona fide revolutionary socialist, while a peasant occupying land in Latin America with the Bible as a guide may at best be considered a “revolutionary in action” if his or her struggle happens to provoke a crisis of the state that leads to a struggle for power.

In my view, rather than operating with a category of revolutionary essence, it should be recognized that all individuals and groups have multiple aspects and identities, as they evolve and as contexts shift. Again, it is not impossible or undesirable to distinguish revolutionary from reformist theory or action, but such a task is much harder to carry out than it appears to those who spend so much of their time putting other groups and individuals into “boxes” — liberal, reformist, centrist, “revolutionary-in-action,” revolutionary, etc.

The borders are always shifting. A group or individual may share features of several of these labels at once, or else be a “revolutionary” with zero impact on the class struggle or a “liberal” such as Martin Luther King who is a galvanizing force for social advancement.

Revolutionary socialists in the United States always have and apparently always will face problematic leaderships at the head of worthy struggles in far-off countries — whether the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, the African National Congress in South Africa, the Lavalas movement in Haiti or the Cuban Communist party. The approach of comparing these leaderships to mythical “true Bolshevik-Leninist parties” and then decrying them as bankrupt, treacherous, etc., is hardly more useful than uncritical adulation. In a way, both attitudes mirror each other by being based on simplistic premises.

The methodological objective required is one that obtains a balance between skepticism about any leadership’s political claims, and a sufficient belief in its potential to act in genuine solidarity.(8) My understanding of past history of the left shows that all leaders are contradictory, including Lenin and Trotsky. Certain individuals appear at times to point the way: women and men who act as leaders in a community, or in a factory. Yet, invariably, even the most extraordinary individual leaders eventually come up against real inadequacies in their capacity to lead, to understand and to commit resources.

The goal of socialist political cadres must be the development of a broad and democratically functioning team leadership, based on an organization institutionalizing multiple tendencies and pluralism, that balances out strengths and weaknesses in order to sustain a movement diachronically as well as synchronically.

A big problem, of course, is that, in an “individualist” culture, such as that which holds sway in advanced capitalist countries like the United States, very few individuals who achieve recognition for leadership talents are willing to subordinate their egos to a team, a problem that has implications for revolutionary practice as for other activities. People desire recognition, gratification and admiration, even if they are not directly motivated by monetary gains. Like many medical doctors who feel that years of grueling self-sacrifice for medical school entitles them to subsequent years of living well, not a few revolutionaries who have made genuine sacrifices for a cause will, after a period of time, feel that this entitles them to various kinds of privileges.

If removed from a national leadership body or an area of work where they have established a satisfying role for themselves, such individuals may, after a period of apparent acquiescence, suddenly undergo a kind of conversion and come up with a series of exaggerated political complaints against the organization — very often ones similar to those held by others who were driven out of the organization previously. Then, if those now making the complaints fail to win a majority, the organization is declared “undemocratic,” even though it was regarded as “the most democratic in the world” just a few years earlier when the individuals now in opposition were part of the majority.

Surely one of the most tragic features of the history of U.S. Trotskyism is the inability of individuals, who were once comfortable in an organization and then on the “outs,” to recognize problems in theory, practice and organization until “one’s own ox is gored.” Like those former Communists who feel that anyone who left the Communist Party at a certain date (usually the one when they themselves left) is all right, but those who remained afterwards are total dupes, many Trotskyists also put a “date” on the degeneration of the group from which they have broken.

In most cases this date roughly approximates the same time as when they were deposed, although some go too far the other way and write off the entire movement from start to finish. These responses reflect all-too-human traits that recur so frequently that they must be acknowledged and addressed; efforts to ignore, deny or simply denounce them have proven inadequate.

The more one critically reads the oral histories and autobiographies of Trotskyist activists that do exist, mostly in unpublished form,(9) the more one sees that a very crucial factor in many splits and disaffections has been the blockage of an individual’s rise to full-time leadership positions. True, most political differences are real, and are even necessary for hammering out a political orientation. Yet the transformation of a difference into the accusation of betrayal by the majority leadership can often be simply the construction of a pretext for an individual oppositionist and his or her circle to break away and set up their own political fiefdom wherein, although smaller, they will constitute the staff of generals.

Sometimes the split is caused by the majority group in power in an effort to remove a potential future threat or distract the membership from objective problems by blaming internal enemies. Usually, however, the dynamic leading to a split occurs on both sides.

None of the above is by any means restricted to Trotskyist or Leninist or even socialist organizations. Anarchist groups and religious sects exhibit the same traits. The question is whether one should continue the Trotskyist tradition of lining up on historical factional sides, as if someone born in 1940 or 1950 or after was actually present as an engaged participant at the time of the “French Turn” or “Auto Crisis.”

This relates to some of the controversies about the so-called “Cannon” tradition. Is the proper appreciation of Cannon, who certainly represents a good deal of what is most recuperable in U.S. Trotskyist history, to be achieved by retrospectively reinscribing oneself as his right-hand man or woman in all the faction fights he ever waged? Is this the most effective way way to combat vulgar and prejudiced anti-Cannonism?

Might it not be more productive to step back and extract whatever is valuable from all points of view in such disputes, to create a richer and more mature political culture that won’t snap so quickly into raging factions, which at the first sign of serious disputation leads to crisis and split?

Clearly the rhetoric of “all-inclusiveness,” and the abstraction of democracy, don’t work. They disorient and incapacitate as one deals with real life situations, such as ultraleft elements in a coalition or organization that really do disrupt and paralyze, and that may even, under the most extreme conditions, have to be ejected for the sake of democratic, majority-rule functioning.

But the older tradition, with its talk of political homogeneity and fidelity to precise (rather than general) program, doesn’t work either. The boundaries of what constitutes homogeneity are variously defined, as are the interpretations of the allegedly “historic program.” The method required, then, must be based on approaches to problems and principles of analysis, and these must be derived from relations to goals.

In sum, why not “drop” Trotskyism altogether?

First, politically active people need continuity if they are going to avoid repeating errors of the past. Those who lived through the 1960s saw in the fate of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) that one could not entirely escape program, coherent organization and a theory of social formations. SDS’s attempt to repudiate the Old Left, instead of critically building upon and advancing its legacy, only hastened the New Left’s demise.

A second reason for coming to terms with and appropriating the best of U.S. Trotskyism — that is, putting it up on the reference shelf alongside the other potentially valuable traditions of class struggle, but perhaps letting it protrude a bit and dressing it in a brighter cover — is that there are recuperable elements in its theory and tradition, far superior to others available.

The Theory of Permanent Revolution, while of course still remaining to be verified, seems to offer the most plausible perspective for liberation of the dominated countries through the combining of bourgeois-democratic and socialist demands.(10) The Trotskyist focus on Workers’ Power — the assessment of strategy as well as the character of a social formation from the perspective of self-control by the producers — and the corollary arguments for separating party and state, and the necessity of revolutionary pluralism, all of which are argued so compellingly in the Fourth International Document on “Socialist Democracy and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat,” provide a crucial foundation.(11) So does much Trotskyist work regarding nationalism and the national question.

Because Trotskyism has had so little success in the United States, the attitude of Trotskyism historically has appeared to be, “if only we were in the leadership, we could set things right — because, if we were in the leadership, the class consciousness of the proletariat and its allies would have to be at a much higher pitch.” In the famous case of Trotskyist policy regarding the Popular Front and World War II, for example, this stance is essentially the legacy that Trotskyism bequeathed — the truism that the only real solution is socialist revolution. That, in turn, is only obtained by refusing to subordinate the interests of the working class to the program of liberal capitalism.

But, Trotskyist or not, all reasonable people ought to be haunted by the questions: What if revolution were not possible then; what if the famous “crisis in leadership” (the failure of correct ideas to win out) were overdetermined by factors that simply could not be dislodged, even if Trotskyist organizations had memberships of tens of thousands? What if, in fact, the Popular Front did not, over all and in every case, facilitate the advance of reaction but was the best that could be produced in certain situations because socialist revolution was not then on the agenda?(12)

As a new generation of revolutionary socialist activists emerges, they will have to go back and reconsider these issues in order to develop a theory and perspective on the course of world history that is genuinely produced and not a mechanical hand-me-down. If those from the Trotskyist tradition stand aside from such reconsideration, or, even worse, participate only as “seasoned experts,” it will only heighten their irrelevance. They must, of course, bring their experiences to bear, but also genuinely listen to people from other traditions and keep an open mind about the possibility of genuinely new issues arising.

Finally, in terms of future directions for research and theory, let me conclude by mentioning one area that has preoccupied me, personally, during the past decade, even before the “Crisis of 1989.”

In my view, the Trotskyist criticism of the U.S. Communist or “Stalinist” movement has been inadequate and off base. I came to this conclusion not only through reading the new scholarship but also as I conducted extensive empirical research based upon about a hundred personal interviews and the examination of sixty or so new archival collections dealing with Communist Party activities.

I raise this not as an academic question, but because I find that young people and left-wing scholars in search of a U.S. radical tradition, especially one that is anti-racist and rooted in the working class, return again and again to the Communist tradition. I don’t believe that this is only because at the height of the New Deal and during the “Grand Alliance” the movement had a kind of “power,” because much of the scholarly interest includes the Third Period of the late 1920s and early 1930s, as well as the Cold War era.

Rather, I believe it is because there is evidence that the struggles and impact of cadres of the CP-USA out-distanced by far any other organized socialist current. Even many who broke bitterly with the CP-USA went on to play admirable roles in struggles during the 1960s and after, and frequently acknowledged the value of their years in the CP-USA. Given this reality, the issue of a compelling and subtle theorization of the U.S. Communist movement also embodies the bigger question of how one critiques and relates to other more successful movements that one nonetheless believes to be profoundly flawed.

Here it is significant to note that many features of the traditional Trotskyist critique of the Communist movement are far and away the most influential in scholarship on the Communist Party, outside of CP-USA circles themselves, of course. This was certainly the case after the end of the 1950s when the low-level anticommunist red-baiters such as Eugene Lyons faded from prominence. This Trotskyist critique, reworked to fit various political perspectives, was embodied mainly in Theodore Draper’s early histories, Cannon’s and Shachtman’s writings, and in writings by Howe, Coser, Phyllis and Julius Jacobson and Bert Cochran.

The view was generally that CP-USA rank-and-file activists were decent people, not dupes of the USSR but dupes of their leaders, who, like the Soviet bureaucracy itself, covered up crimes and perpetrated lies out of self interest (varying from monetary gain and power to more subtle psychological needs). Moreover, these leaders remained leaders mainly by fidelity to Stalin’s shifting policies, in turn determined by Stalin’s own need to maintain power in the USSR.

Of course, revolutionary socialists like Cannon and the Jacobsons argued for such analyses from an uncompromising anticapitalist and anti-imperialist perspective, while others, shading off into liberalism, combined features of this critique with very different politics.

In 1993, however, we see that most current scholarship on the CP-USA by leftists, most of whom are or were activists and “on the side of the angels,” is in aggressive rebellion against this legacy. The main defender of Theodore Draper is Harvey Klehr, a neo-conservative.

This rebellion is not at all because many of these scholars, mostly middle-aged professors of history, have been in or around the CP-USA; actually, many of these had a connection with rival currents, including the C.L.R. James tradition, Maoism, and even Trotskyism. I won’t repeat here what I’ve already published in reviews of the books by Paul Buhle, Mark Naison, Maurice Isserman, Robin Kelley, and Ellen Schrecker.(13)

What I think is crucial to emphasize here is that this scholarship on the CP-USA, although I politically disagree with much of it, has rendered the whole subject of U.S. Communism far more absorbing, useful and relevant than ever before, and more than the study of Trotskyism has ever been. This is because these scholars have moved from a focus on documents, resolutions and parallels with Soviet policy to paying attention to human dimensions, and engaging gender and race issues — and because, while not eschewing the idea of commitment, many of these scholars have the ability to step back and examine a variety of perspectives on a problem somewhat dispassionately, according to the attitude popularly attributed to Lukács, “partisan but objective.”

What this means is that those trying to sustain what is useful from the Trotskyist tradition need a less-grandiose conception of Trotskyism’s historic role. The view that the task of modern Trotskyists is to “reclaim a historic program” by using their publications to distinguish themselves from other political currents through defense of “the Trotskyist program” is far too simplistic.

There are too many opinions about what constitutes “the real historic program” of Trotskyism, and, by incanting such mystical phrases, one will only end up confusing oneself with, not distinguishing oneself from, the discredited legacy of Trotskyist sectarianism. In the tradition of “American Trotskyism,” much of this outlook flows from the belief held by James P. Cannon in the 1940s that the Socialist Workers Party was the already-constructed vanguard, with its main objective being to win leadership of the masses.

Although one has good grounds to believe that this kind of faith was necessary for Cannon and the SWP to survive the difficulties of the period, it surely must be rejected as a model for today, even though the basic idea appears in Cannon’s otherwise inspiring “Theses on the American Revolution”:

“The revolutionary vanguard party, destined to lead this tumultuous revolutionary movement in the U.S. does not have to be created. It already exists, and its name is the Socialist Workers Party. It is the sole legitimate heir and continuator of pioneer American Communism and the revolutionary movements of the American workers from which it sprang…The fundamental core of a professional leadership has been assembled….

“The task of the SWP consists simply in this: to remain true to its program and banner, to render it more precise with each new development and apply it correctly to the class struggle; and to expand and grow with the growth of the revolutionary mass movement, always aspiring to lead it to victory in the struggle for political power.”(14)

This kind of thinking was not an aberration of the movement, but flowed directly from the tradition of “American Trotskyism.” Similar ideas appear in an article by Morris Stein, one of Cannon’s most trusted supporters, who served as SWP National Secretary when Cannon was imprisoned under the Smith Act:

“We are monopolists in the field of politics. We can’t stand any competition. We can tolerate no rivals. The working class, to make the revolution can do it only through one party and one program. This is the lesson of the Russian Revolution. That is the lesson of all history since the October Revolution. Isn’t that a fact? This is why we are out to destroy every single party in the field that makes any pretense of being a working-class revolutionary party. Ours is the only correct program that can lead to revolution. Everything else is deception, treachery. We are monopolists in politics and we operate like monopolists.”(15)

No doubt there are those who can sugar coat and speciously “interpret in the appropriate context” such statements, or even try to minimize them in light of the fact that both writers (Cannon and Stein) modified their views as time went on.

But the Trotskyist tradition has no hope of accomplishing anything more than the generation of small, sectarian groupuscules unless it breaks radically with the key features of this outlook. It must instead be recognized that no program or group of cadres or organization exists as “the heir and continuator” of the revolutionary tradition; that the programmatic task is not to render it more precise and apply it “correctly” but to profoundly revamp it in friendly interaction with rival perspectives, aimed at developing method more than precise policy; that leadership (even if united and to some degree centralized) is not something that should fall into the hands of a single group but should grow organically from the struggle with various kinds of political activists participating side-by-side with (and with veterans learning from) the participants more than “leading” them; and that one should be an anti-monopolist in the field of politics, learning from and defending the rights of political rivals.

However, to repudiate the strong elements of sectarianism, leader idolatry, hairsplitting, and so forth, which have afflicted and disabled U.S. Trotskyism, has nothing in common with the vulgar anti-Trotskyist views that the movement produced nothing of worth, that all forms of anti-Stalinism must lead to deradicalization or “objectively” aids reaction, that Trotskyism is simply Stalinism without power, and so forth.

To sum up: TROTSKYISM!!! is dead. Long live trotskyism.

I am grateful to several scholars and activists who gave me critical feedback on a draft of this essay: Steve Bloom, Paul Le Blanc, Peter Drucker, Christopher Phelps, Ellen Poteet, and Patrick Quinn. However, I alone am responsible for the analysis and any errors.

Notes

- An outstanding example of this creative yet rigorous approach is Paul Le Blanc, Permanent Revolution in Nicaragua (New York: Fourth Internationalist Tendency, 1986).

back to text - The trend was first discussed by Max Shachtman in “Footnote for Historians,” New International IV (Dec. 1938): 377-9, and elaborated by Daniel Bell in Marxian Socialism in the United States (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1967), 154-57.

back to text - The Trotskyist organization Spark frequently exemplifies this.

back to text - In observing the articulation of policy in the Socialist Workers Party, I frequently found the same basic analysis reasonable when presented by individuals such as George Breitman and Fred Halstead, but shrill and simplistic when appearing in the Militant or presented by other leaders, including those who had graduated from the nation’s most elite colleges.

back to text - Some Trotskyists try to strengthen their achievements by retrospectively taking credit for the Russian Revolution and other social transformations. (Yugoslavia as an example of turning the anti-fascist war into a socialist revolution; Cuba as an example of “revolutionaries in action” carrying out an “unconscious Trotskyist” perspective, etc.). Today, of course, after the events of 1989 and the assault on Bosnia, taking “credit” for October 1917 and Yugoslavia, even with the Trotskyist analysis of these societies’ degeneration and deformation, appears even more tenuous than before.

back to text - Naturally the adherents of these theories don’t believe they are presenting dogmas but the “true laws of motion” of these societies. As I have argued in The New York Intellectuals, 188-89, none of these theories persuasively accounts for all aspects of these societies, and each seems to be based on one or more impressive points of analysis; therefore, a synthetic embodiment of these and other theories is the most useful perspective with which to work. Unfortunately, for most Trotskyists, absolute fidelity to their particular interpretation of a specific theory of Soviet-type societies is their political touchstone.

back to text - Actually, I favor using the term “revolutionary” with a great deal of caution. An individual with a revolutionary consciousness, such as a union official, may be operating in a structure that prevents revolutionary practice; likewise, a revolutionary-minded peasant may simply have no collective instrument to realize revolutionary action. On the other hand, what is offensive and destructive is the declaration made by adherents of tiny parties, that have no possibility of meaningful revolutionary action, that they themselves are “revolutionary” in distinction to those engaged in genuine social struggles but who lack the “revolutionary program.”

back to text - This does not mean marching in a parade with signs and literature supporting the “masses” while denouncing their leaders as “criminal sellouts.”

back to text - Unpublished autobiographies exist in various forms by Carl Feingold, Milton Genecin, George Novack, Max Shachtman, Arne Swabeck, Stan Weir and B.J. Widick.

back to text - See the valuable exposition by Michael Löwy, The Politics of Uneven and Combined Development (London: Verso, 1981). Nevertheless, it doesn’t follow that this aspect of Trotskyist theory is unproblematic, especially from the perspective of critiquing the “stagism” that has plagued virtually all of Marxist political analysis.

back to text - ”Socialist Democracy and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat,” Special Supplement to Intercontinental Press Combined with Inprecor (January 1980): 210-25.

back to text - Clearly there are specific examples where Popular Front policy did facilitate the advance of reaction, such as the May-June 1937 events in Barcelona, dropping the fight for independence from Britain in India, and so forth.

back to text - The reviews of all but Kelley have been reprinted in Wald, The Responsibility of Intellectuals (Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1992); the review of Kelley appears as “The Roots of African-American Communism,” Against the Current 46 (September-October 1993): 33-36.

back to text - Cannon, The Struggle for Socialism in the “American Century,” 271.

back to text - SWP Internal Bulletin, Vol. VI, no. 13 (December 1944): 10.

back to text

ATC 55, March-April 1995