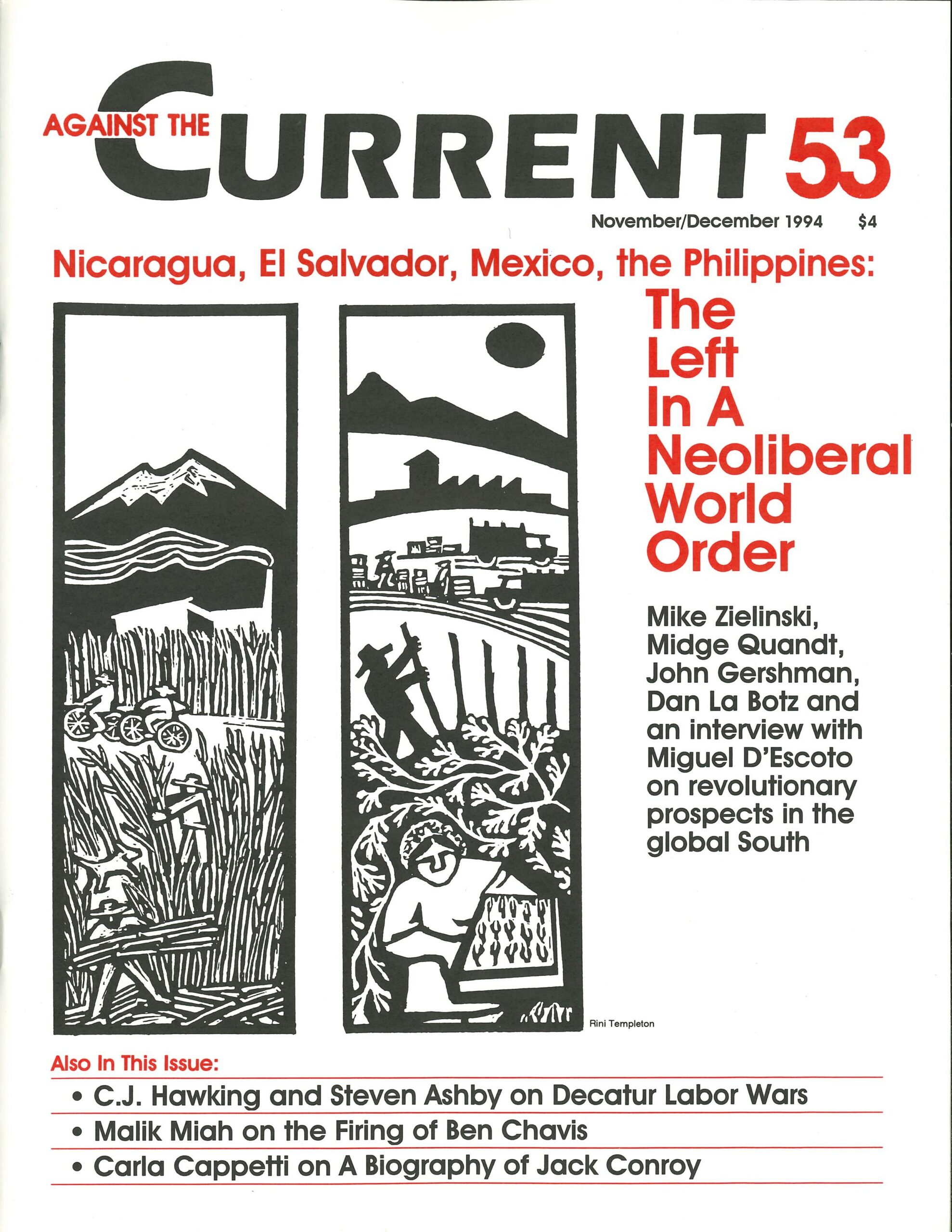

Against the Current, No. 53, November/December 1994

-

Clinton's Best-Laid Plans

— The Editors -

The Firing of Ben Chavis

— Malik Miah -

Decatur Labor Fights On

— C.J. Hawking & Steven Ashby -

Mexico: Zedillo Wins, the Struggle Continues

— Dan La Botz -

Gays & Lesbians in Chile Fight Back

— Emily Bono -

Rebel Girl: Family Planning Without Women??

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: Family Values for Beginners

— R.F. Kampfer - The Left Reconstructs

-

The FMLN After El Salvador's Election

— Mike Zielinski -

El Salvador: A Political Scorecard

— Mike Zielinski -

Sandinismo's Tenuous Unity

— Midge Quandt -

Keeping the Dream Alive

— interview with Miguel D'Escoto -

Debates on the Philippine Left

— John Gershman -

The End of American Trotskyism? (Part 1)

— Alan Wald - Reviews

-

Massacre in the Guatemalan Jungle

— Dianne Feeley -

John Beverly's Against Literature

— Tim Brennan -

Jack Conroy, Worker-Writer in America

— Carla Cappetti - Dialogue

-

What Genovese Knew, And When

— Christopher Phelps -

On the PDS: An Exchange

— Eric Canepa -

On the PDS: A Reply

— Ken Todd - In Memoriam

-

Peter Dawidowicz, 1943-1994

— Nancy Holmstrom -

Clarence Davis, Gulf War Resister

— David Finkel -

Earning the Title

— Clarence Davis -

Desert on Detroit River (To Laurie)

— Hasan Newash

Alan Wald

WHY SHOULD REVOLUTIONARY-SOCIALIST political activists in the 1990s be concerned with the history and theory of U.S. Trotskyism?(1) Radical anticapitalist activists today are feminists, opponents of imperialism and Eurocentrism, militant supporters of gay and lesbian rights, committed to ecological transformation, and, in light of the “bad example” set by so many self-proclaimed “Leninist” organizations, skeptical of self-proclaimed vanguards. Why should they give signal attention to the ideas and experiences of those who identified with Trotskyism in the United States? Why not just put Trotskyism on the shelf next to Debsian socialism, anarchism, Black nationalism, Communism, and a variety of other left-wing experiences from which activists can draw upon as it suits their particular needs?

After all, it has been sixty-six years since James P. Cannon, Max Shachtman, Antoinette Konikow, and other expelled members of the U.S. Communist Party established the U.S. Trotskyist movement with one hundred people in 1928. Only those who live within a highly-circumscribed reality can fail to see that, in a society where winning the support of the majority means the ability to influence millions, the balance sheet of the political accomplishments of Trotskyism after six-and-a-half decades tends toward the negative. Thus it is fair to raise the question, “Are we now at the end of `American Trotskyism?’”(2) And one should not be astounded if many young activists reply, “Yes, we are.”

I. The Test of Two Eras

For starters, one has the discouraging evidence of the net gains for Trotskyism after having passed through two major eras of political radicalization, the 1930s and the 1960s. In these periods, the Trotskyist movement (a broad term that I’ll use for the moment to include all of its components), although it grew and made noteworthy contributions, never achieved anything remotely like a sustained organizational or political breakthrough. If one takes an overview or if one assesses the situation from the perspective of long-term gains, Trotskyism never clearly outdistanced rival currents on the political left, particular those associated with the Communist and Social Democratic traditions.

Those forces calling themselves “Trotskyist” today are not quantitatively stronger in political influence than groups that have shifted away from Trotskyism such as the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and Workers World Party (WWP), nor those from the Communist tradition, the Communist Party (CP-USA) and the Committees of Correspondence (CofC). It is harder to judge the political weight of groups calling themselves “Trotskyist” in comparison to the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), especially since the existing “Trotskyist” groups rarely collaborate and generally consider all the other “Trotskyists” either hopelessly sectarian or irredeemably opportunist. The combined weight of all such “Trotskyist” groups, even if one could imagine them working together for a moment or two, is probably even less than the disparate forces that come out of the Maoist tradition (Marxist-Leninist Party, Communist Labor Party, “Crossroads,” Progressive Labor Party, Revolutionary Communist Party, and so forth).

Only in very limited frameworks of “moments” when a campaign or strike was victorious, or a political strategy appeared to win out, as in the 1934 Minneapolis Teamster Strikes or the 1960s U.S. anti-Vietnam War movement, can one talk of “Trotskyism’s achievements” in the United States as major, although certainly, in addition to these two, there are a few other memorable ones. Yet, at the end of each of these major radical eras, Trotskyism was not only smaller and less influential than it had been at their height (late 1930s and late 1960s), but it had produced a new round of bitter splits and intra-Trotskyist recriminations that only further divided and confused the political landscape.

Even more distressing, the first era, the 1930s, may well have produced greater Trotskyist accomplishments than the more recent era, the 1960s; a decrease in achievements was also the case with the pro-Soviet Union Communist movement, the CP-USA. At the least, we should recognize that, in terms of membership numbers and political authority, forces calling themselves “Trotskyist” in the U.S. were not significantly stronger at the end of the 1960s/70s radicalization than they had been decades earlier, at the end of the 1930s/40s radicalization.(3)

If one tries to identify leading figures in this history of U.S. Trotskyism, almost all belong to the generation of the 1930s or earlier — James P. Cannon, Max Shachtman, Antoinette Konikow, C. L. R. James, Farrell Dobbs, Hal Draper, George Novack, George Breitman, Joseph Hansen, etc. How many well-known figures in the trade union movement, the women’s movement, the African American or Latino movement, or any other social movement were won to Trotskyism in the 1960s?

At best, there are a handful of left-wing unionists and labor educators who came out of the International Socialists (heir to the left-wing Shachtman tradition). Fred Halstead, the only really prominent Trotskyist in the anti-war movement, was won to Trotskyism in the 1940s and was the son of Trotskyists. While a number of 1960s activists went on to become impressive scholars and professionals, none have at this date achieved the intellectual stature of Sidney Hook, Meyer Schapiro, Irving Howe, Leslie Fiedler, or the Partisan Review editors.(4)

In fact, one might conclude that Trotskyist forces are in greater disarray in the 1990s than they were during the post-World War II labor upsurge of the late 1940s (just prior to the onslaught of the antiradical witch-hunt). At that time the two major groups, the Socialist Workers Party and the Workers Party, numbered about two thousand and were leading city-wide struggles in major urban centers.

The most likely moment comparable to U.S. Trotskyism’s present situation might be in the mid-late 1950s, following numerous political crises that wrecked the Trotskyists in the Socialist Workers Party, leaving it with less than four hundred members after conflicts about Stalinism and the labor movement, Hungary, China, Cuba, and the early civil rights movement. At that time, Trotskyism experienced, as it did also during the new and perplexing political period of the 1980s, a hemorrhage of splits and expulsions which created the Workers World Party, the Spartacist League, the Workers League, and the Freedom Socialist Party, among others. The Trotskyists in the Independent Socialist League, led by Shachtman, were fractured by Shachtman’s turn to the right wing of the Socialist Party. The supporters of the journal American Socialist, a former Trotskyist grouping led by Bert Cochran and Harry Braverman, dissolved in 1959. The state capitalist currents led by C. L. R. James and Raya Dunayevskaya were irreconcilably ruptured into rival groupuscles, with News and Letters separating from Correspondence in 1955.

Of course, one might speculate that, maybe, the left is perhaps now on the verge of yet another 1930s or 1960s upheaval, and fantasize that the political crises of the last decades have cleared the way for the “True Revolutionaries” with the “Correct Program” and “Leninist” organizational policies to make big gains in the coming epoch. All that would be needed are aggressive “party-building” tactics and promotion of “the historic Trotskyist program,” together with some “principled regroupment” with other self-proclaimed Trotskyist organizations to demonstrate “non-sectarianism.”

Current economic, political and cultural trends tend to confirm many of the classical Marxist criticisms of capitalism, and portend new social crises. Socialism will never be advanced and defended unless its partisans take the step of constructing collaborative organizations to participate in struggles and advance theory. But several over-riding new features must be taken into account before one moves from point A, the coming crises and need for organization, to point B, a revival of Trotskyism that will lead to a breakthrough. Many of these new features of the 1990s have to do with the near-disappearance of what Trotskyists have called “Stalinism,” i.e. bureaucratized post-capitalist or non-capitalist societies. “Stalinism” was a model of socialism for millions, but for Trotskyists it was a counter-model representing socialism’s betrayal.(5)

The historical appeal of Trotskyism in the United States was largely based on its claim to combine what was liberating in the experience of the October Russian Revolution and subsequent, similar social transformations, with a rejection of what was negative. Many small groups can accomplish effective political work on a local level, through the talents of devoted activists, even if their world-view is misguided. If one is simply an effective activist in one’s community, one can play a positive role and a few people will join one’s group — which is why many intelligent and committed activists will continue to join various small leftist organizations whose individual members work alongside and make a favorable impression on them.

But to survive and expand in numbers and influence over various, politically diverse periods of time, to obtain a national coherency, and a kind of “moral authority” extending far beyond one’s actual members, a group must fill some plausible space on the political terrain. To some extent, this was historically the case with U.S. Trotskyism, inasmuch as it stood to the left of the reformism of social democracy and was unencumbered by the embarrassing albatross of the Stalinist societies.

The “dual assessment” of the October legacy distinguished Trotskyist analysis, highlighting the progressive and the reactionary aspects of the process of the Russian Revolution. Different trends within Trotskyism theorized that dual assessment in different ways when addressing the dynamics of non-capitalist societies, producing analyses that characterized these societies as degenerated workers states, state capitalist states, bureaucratic collectivist states, and so forth, all of which had various interpretations and applications too labyrinthine to adequately recapitulate here.(6) The collapse of Stalinist societies in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, coming at the time that it did and in the way that it did, vastly undermines for most people the notion that there is anything positive to be recouped from that experience at all.

There are very few signs of nostalgia for the traditions of the October Revolution among those outside of the formerly privileged groups in post-Soviet societies, even though there have been social losses — in areas such as women’s rights, job security, and the disappearance of aid, albeit token, to anti-imperialist struggles — that would be regarded by progressive-minded people as unfortunate sacrifices.(7)

That enigmatic Soviet dissident, Yevgeny Yevtuskenko, summed up the feelings that now exist among many former Soviet citizens for the tradition of October in the poem “Goodbye, our Red Flag,” which he read to an overflow crowd on July 23, 1993, the occasion of his sixtieth birthday:

Goodbye our Red Flag,

You were our brother and our enemy.

You were a soldier’s comrade in trenches,

you were the hope of all captive Europe,

But like a Red curtain you concealed behind you

the Gulag

stuffed with frozen dead bodies.

Why did you do it,

our red Flag?(8)

What may be most important is that the collapse of the USSR and Eastern European society did not occur due to the resurgence of progressive forces from within: There were no mass insurgencies based on a positive assessment of the legacy of the Russian Revolution — whether that positive assessment referred to social gains of bottom-up and democratically-controlled nationalizations or simply to a memory of working class power. Instead, masses of people associated the 1917 Revolution with the stultifying bureaucracy that disgusted them. This rejection of the Russian Revolution was the case, even though there were stages in the collapse where the potential for a resurgence of a revolutionary-socialist perspective appeared to be about to surface; for example, the manifestations of a drive for workers’ power evidenced in the very early days of Polish Solidarnosc, and in the ideas of a few genuine socialist currents extant when the USSR finally collapsed.(9)

The Soviet collapse occurred under the ambiguous rubric of “democracy against authoritarianism.” At the same time, there was the Chinese Stalinist regime staving off its own demise through the massacre of dissident students and others. There were also general crises of a different nature in various left-wing movements around the world, as in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and South Africa. But nowhere was there anything suggesting a substantial turn in the direction of that Trotskyist “dual assessment.” Indeed, Trotsky’s name came up only in the USSR, not in China, Central America or South Africa, and usually in the context of a refusal of the reformers to rehabilitate him, and their rejection of his legacy in favor the lesser figure of Bukharin. No significant current within the USSR or anywhere else took up Trotskyism as a viable alternative, or even as a starting point for a socialist renaissance.

The assessment of Alex Callinicos, a leading theoretician of the British Socialist Workers Party, at the beginning of his short book Trotskyism (1990), strikes me as quite accurate. According to Callinicos, Trotsky, the person and historic actor, remains of considerable interest to some scholars and activists, because of his stature as a thinker and writer, and because he had the “good fortune to have his life recorded by Isaac Deutscher in what is without doubt one of the outstanding biographies of our time.” On the other hand, Trotskyism itself is largely dismissed “as a welter of squabbling sects united as much by their complete irrelevance to the realities of political life as by their endless competition for the mantle of orthodoxy inherited from the prophet.”(10)

Beyond this, the vision of socialist transformation represented by the paradigm of the October Revolution seems to have less credibility than was the case for earlier generations of radicals. At the moment, it is unclear what alternative experiences will form the foundation for a new paradigm of socialist revolutions.(11) We may well see in this decade transformative upheavals in South Africa and Brazil, which, from the point of view of Marxist abstractions, could have more promise than October 1917. After all, the prospects for anticapitalist revolution in those countries are enhanced by the existence of organizations professing to have learned lessons from failures of the past, and of a mass industrial base that was not present in Czarist Russia or, for that matter, in China, Cuba or Nicaragua. Yet even if such upheavals occur, one cannot be blindly optimistic. Rather than the achievement of socialism, the consequences could alternatively be the emergence of neo-colonialism in South Africa or an “Allende-like” catastrophe in Brazil.

Even more disturbing, specifically in regard to the United States, one must now acknowledge that the main explanation for the failure of Trotskyist traditions to make a “breakthrough” back in the 1930s is not applicable to Trotskyism’s failures in the 1960s and after. During the 1930s and 1940s Trotskyism could make no real headway because of the overwhelming political weight of the CP-USA, and the unquestioned authority of the Soviet Union as a bulwark against fascism (the eighteen-month period of the Hitler-Stalin Pact notwithstanding) during World War II.

The radicalization of the 1960s, however, occurred in a qualitatively new situation. The Trotskyists began that decade with a core of trained militants numbering in the hundreds; the Communist party had a somewhat demoralized residue of a few thousand. Within a short time the relationship of forces was roughly equal, with the CP having a stronger apparatus, but the Trotskyists (especially of the Socialist Workers Party and the International Socialists) a more youthful composition. Trotskyist accomplishments in the all important anti-Vietnam war movement were probably more significant than those of the CP, and, as a result of sending members into industry in the 1970s, Trotskyist cadres were clearly more important than the CP in at least one union, the Teamsters. Still, all Trotskyist groups ended that period with exploding splits instead of a great leap forward — enjoying the same fate as the Communists and Maoists.

Moreover, regarding the crucial role of racism in the U.S., the Maoists had a much greater influence on Third World radical currents of the 1960s in the U.S. than any Trotskyists. Trotskyists operated on a perspective of Black workers constituting the vanguard, and most Trotskyists (the SWP and International Socialists) held a subtle theory supporting nationalist struggles of the oppressed. But even though the SWP had an early and sophisticated appreciation of Malcolm X, not to mention a friendly relationship with him, it and other Trotskyist groups accomplished far less in recruitment, influence and leadership of African Americans than even the CP, which was anti-Malcolm X and anti-Black nationalist.(12)

For me, the experience of the 1960s and ’70s, regarded with the hindsight of nearly a quarter of a century, closes the discussion on earlier paradigms of Trotskyism as models for leading sustained and national-level emancipatory social struggles in the United States under its own banner. If I’m wrong about this, then one should see the growth in influence and authority of at least one of the dozen or so contending organizations that are attempting recreate that older model in various ways, such as Socialist Action, which is based on a Trotskyist strategy successful in the 1960s-70s (particularly that used to build the anti-war movement), and the Spartacist League, purporting to reproduce Trotskyist strategy of the 1930s and 1940s (particularly that used to critique Popular Frontism).(13)

However, I anticipate that neither can surpass the figure of a thousand members (and I’m probably being very generous here) without suffering splits or else undergoing major political and organizational rethinking and restructuring, which would mean possibly falling into the hands of a new and very different kind of leadership. In my view, it is much more likely that activists emerging from Trotskyist experiences can play a more productive role as a well-integrated current (not tendency or faction) within a broader organization of the far left.

In sum, after the experience of the radical era beginning in the 1960s, one can no longer blame Trotskyism’s failure as an autonomous tendency on the greater material resources of Stalinism. One can, of course, always find other “objective conditions” to blame; for example, one can say that, although Soviet-type Stalinism in the 1960s was not the verwhelming force it once was, the U.S. working class was not in the 1960s the major player it had been in the 1930s or even late 1940s due to post-war prosperity, the bureaucratic stranglehold of the union bureaucracy, and illusions in the Democratic Party. If the working class had been freed of these and therefore at center stage, then Trotskyism would have had its day.

Or one can start blaming the leading groups of the time; for example, arguing that, if the Socialist Workers Party had not committed this or that “sin” (if it had not built a single-issue anti-war movement, “tail-ended petty-bourgeois nationalism and feminism,” abandoned the theory of Permanent Revolution — one can fill in one’s political “crime of choice” here), then today there would be a “mass Trotskyist party.” However, sixty-five years of blaming objective conditions, and blaming more successful rival groups, for such meager results(14) — which is probably today, at best, a dozen squabbling Trotskyist and former Trotskyist organizations of between twenty and five hundred members (most of them closer to twenty) in a country of millions — is an explanation that should be pretty hard for rational individuals to swallow.

Naturally, “objective conditions” must be assessed, and there is no question that the entire left is organizationally, if not also politically, in crisis, so we are not talking about a defect unique to Trotskyism.(15) But the canonical means that Trotskyism has historically employed to overcome difficult objective conditions now appear to have exhausted themselves. So, for me, the discussion now shifts to what elements within the Trotskyist tradition may be retained as components of the contemporary struggle. Which ones need to be revamped? Which ones need to be rejected? How important are any of these in relation to the legacy of other radical traditions, or to the newest lessons to be drawn from emancipatory struggles of the present time?

Notes

- I am grateful to several scholars and activists who gave me critical feedback on a draft of this essay: Steve Bloom, Paul Le Blanc, Peter Drucker, Christopher Phelps, Ellen Poteet, and Patrick Quinn. I however, I alone am responsible for the analysis and any errors.

back to text - The term ‘American Trotskyism” is the historic one for Trotskvism in the United States. Its use is problematic today when, increasingly, “America” is understood as a hemispheric entity.

back to text - The most reliable information I have on membership numbers for the SWP comes from a series of letters I received from George Breitman on July 17, July 30, and August 9, 1985. His view is that the following figures, from convention records, are accurate: 100 for 1929; less than 200 for 1931; 429 for 1934; 1520 in 1938; 1095 in 1940; 645 in 1942; 850 in 1944; 1,470 in 1946; 1,277 in 1948; 825 in 1950; 758 in 1952; 480 in 1954; 434 in 1957; 399 in 7959; 473 for 1967; 441 for 1963; 420 for 1965; 385 for 1967; 500 for 1969; 791 for 1971; 1125 for 1973; 1125 for 1975; 1454 for 1976. Breitman noted that figures are difficult to compute for the fusion of the CI,A and Muste’s American Workers Party; the former claimed 429 at that time and the latter less than 300 — but some of the AWP members switched to the CP-USA or dropped out. Breitman estimates that between 500 and 600 actually entered the SP, and that it is difficult to get precise fig ures for the period inside the SP because all factions were inflating their numbers by various means. Breitman was also dubious that one could come up with estimates for active sympathizers, or the proportion of inactive members, or even a general figure for how many individuals actually “passed through” the Trotskyist movement over the decades. After 1976, the figures for the SWP began to decline.

back to text - This claim may be a weak point since many careers have yet to reach their zenith. Moreover, it is still difficult to “name names” of individuals in mid-career once organizationally connected with U.S. Trotskyism, due to prejudice in our society, especially in the universities, against those who have held membership in revolutionary organizations. Eventual!y however, this topic may be worth of a full-scale study, comparing not only the two generations but comparing Trotskyist-influenced intellectuals of various countries and Trotskyist-influenced intellectuals with leftists from other traditions.

back to text - Not “betrayal” in the sense of a personal sell-out; Trotsky’s The Revolution Betrayed (1937) presents a materialist analysis of the social and historical conditions for the rise of the Stalinist bureaucracy.

back to text - See my discussion of the comparative merits of some of these theories in The Now York Intellectuals (Chapel I Till, N.C.: University of N. Carolina Press, 1987):186-92. AIso, Paul Bellis’s Marxism in the U.S.S.R.: The Theory of Proletarian Dictatorship and the Marxist Analysis of Soviet Society (Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1979), provides a useful survey of the theories of Trotsky, Shachtman, Burnham, Cliff, James, Dunaycvskaya, and others.

back to text - There are, of course, signs of nostalgia for the particular version of “October” associated with the rule of the bureaucratic elite, expressed by those associated with that elite who have mobilized some substantial demonstrations.

back to text - New York Times, 24 July 7993: 4.

back to text - See collection of essays edited by Marilyn Vogt-Downey, The USSR 1987-1991: Marxist Nerspectives (Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Hiumanities Press, 1993).

back to text - Alex Callinicos, Trotskyism (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Dress, 1990): 1-2.

back to text - As in regard to many other topics treated in this essay, the “paradigm problem” is itself worthy of a separate study. For example, it is worth recalling that the “model” theorized by October itself involved a particular interpretation of earlier experiences, such as the Paris Commune of 1871. Thus it is not at all unlikely that future theorizations of revolutionary experience may reincorporate both of these in new forms. Moreover, any new paradigms will no doubt draw upon May 1968, the Sandinista Revolution, etc., not to mention more recent cultural work based upon previously underestimated thinkers such as Gramsci. What is perhaps most important to recognize is that much of Trotskyism overemphasized the Bolshevik experience more is a model to be emulated (albeit with “adjustments”) than a paradigm for imagining revolutionary processes and anticipating their problems.

back to text - One part of the explanation for this failure may tic in the understandable choice that the Socialist Workers Party made to prioritize the building of a mass antiwar movement around the slogan, “Out Now.” This led it to orient the bulk of its membership to working on the relatively elite white campuses and in coalitions with white liberals around the “single issue’ app roach. Many Maoist groups contributed little to building a mass antiwar movement and oriented its cadres to communities and workplaces of people of color with more revolutionary-sounding demands. The Communist party possessed a tradition of stronger links to communities of people of color, and benefitted from the Soviet Union’s material aid to certain Third world Liberation struggles. In addition, it might be noted that Maoist groups gave uncritical support to the Chinese revolution, and the Communist !’arty to the Cuban Revolution and Communist Party of Vietnam. ‘I he various kinds of “critical support” offered by “Trotskyist groups, though quite justified, were frequently perceived as undermining the struggle or even “racist.”

back to text - I suppose it is possible to object that neither of these groups, nor any of the other existing ones, are really carrying out” the traditions of U.S. Trotskyism. Yet one is faced with the problem: Why is it that with so many efforts to realize historic “American Trotskyism,” the results are consistent!y so awful? Is the problem simply the lack of the single guru, the new James P. Cannon, who can put it all together—or something deeper and more strategic?

back to text - These results are today probably, at best, a dozen squabbling Trotskyist and former Trotskyist organizations of between twenty and five hundred members (most of them closer to twenty) in a country of millions.

back to text - Indeed, among the next steps following this particular essay should be a comparative analysis of the situation of U.S. Trotskyism within the contexts of the U.S. as well as international left.

back to text

ATC 53, November-December 1994