Against the Current, No. 48, January/February 1994

-

Those Giant Sucking Sounds

— The Editors -

Voucher Mania: Will It Spread?

— Joel Jordan -

The Unmaking of Mayor Dinkins

— Andy Pollack -

The Illusion of Middle East Peace

— Nabeel Abraham -

An Information Center for the Russian Workers' Movement

— Alex Chis and Susan Weissman - Defend Human Rights in Russia!

-

On Mythology and Genocide

— Branka Magas -

Behind the Turmoil in Italy

— Jack Ceder -

The Rebel Girl: Having A Bobbitt Sort of Day?

— Catherine Sameh -

Random Shots: The Spirits of the Season

— R.F. Kampfer - Chronic Fatigue Demonstration

-

Working-Class Vanguards in U.S. History

— Paul Le Blanc -

Puerto Rico's Plebiscite

— Rafael Bernabe -

Section 936: A Corporate License to Steal

— Working Group on Section 936 -

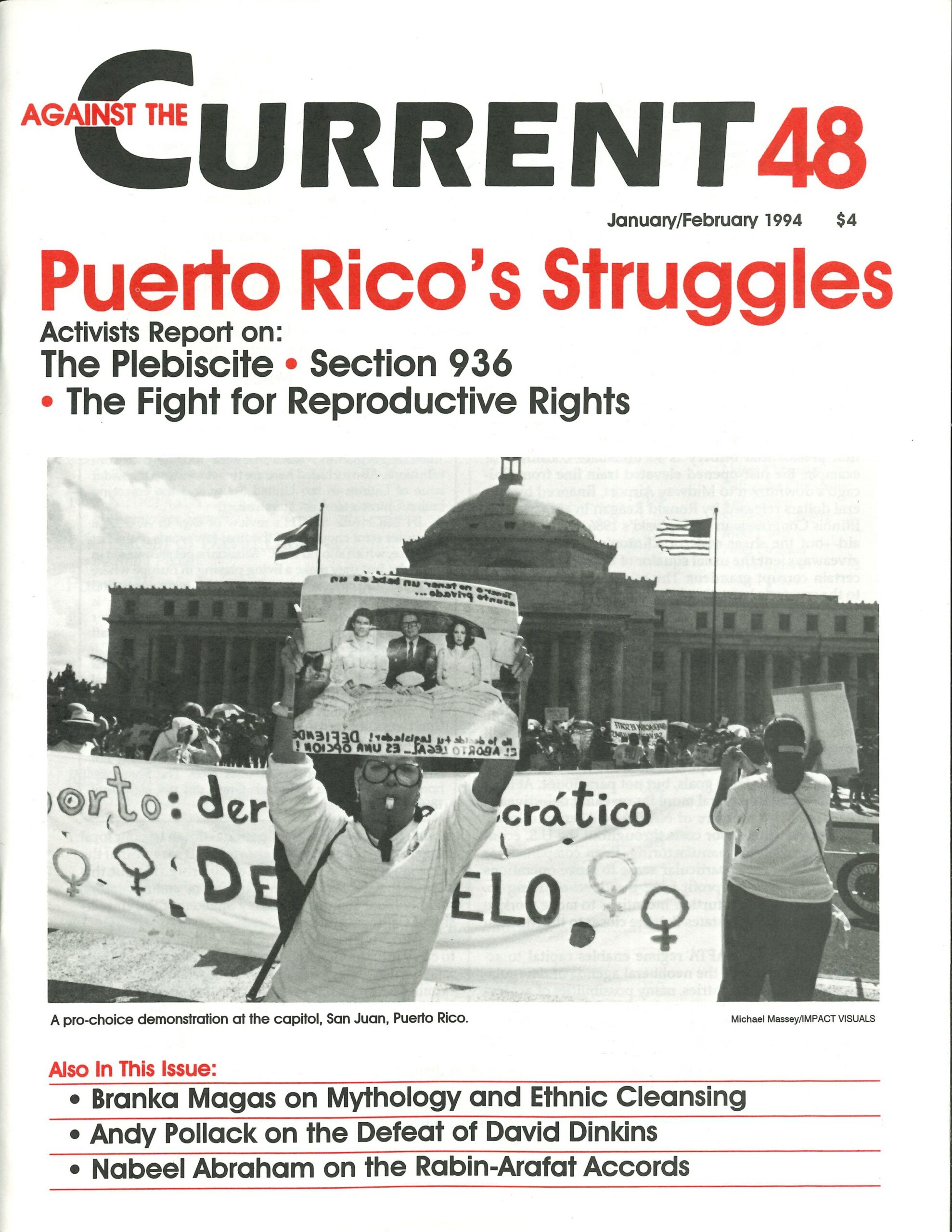

Confronting Anti-Choice Forces in Puerto Rico

— Ruth Arroyo, Rafael Bernabe and Nancy Herzig -

Al Norte

— Ruben Auger - Notes

-

Latinos: One Group or Many?

— Samuel Farber -

Latina Writers Defying Borders

— Norine Gutekanst - Reviews

-

Socialism as Self-Emancipation

— Justin Schwartz - Remembering E.P. Thompson

-

E.P. Thompson: 1924-1973

— Michael Löwy -

E.P. Thompson as Historian, Teacher and Political Activist

— Barbara Winslow

Andy Pollack

THE DAY AFTER David Dinkins, New York’s first Black mayor, lost his bid for re-election, a press conference held by prominent Black politicians encouraged New Yorkers to consider formation of a third progressive party. The Reverends Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton and State Senator David Paterson criticized the Democratic Party for securing the election of white candidates Mark Green and Alan Hevesi to citywide posts while failing to pull out all the stops for Dinkins. While Giuliani beat Dinkins 51 to 48% (903,000 to 859,000), Dinkins’ running mates Hevesi and Green beat Giuliani’s slate by 15 and 24% respectively over Herman Badillo and Susan Alter. Since the press conference, several meetings of Black politicians and community activists have been held to throw around this idea, and more are scheduled.

Adding insult to injury for Blacks in New York, speculations in the media about potential challengers to Giuliani in 1997 mention only whites. Manhattan liberal Ruth Messinger—who succeeded Dinkins as borough president and was a strong ally of his—is openly talking of her conviction that she will be mayor some day. What’s more, the top five citywide elected posts are now held by white men. (Carl McCall recently became the first Black to hold statewide office, and not surprisingly is trying to convince fellow Black politicians to drop plans for a new party).

Analyzing this re-exclusion of Blacks from electoral power, Paterson asked “Does that mean that the Dinkins administration was some sort of fad? That seems to be the case in other cities.” Some of those calling for a new party are encouraging a run against Governor Cuomo next year, criticizing Cuomo for releasing a report judgmental of Dinkins’ handling of the Crown Heights affair in the heat of the mayoral campaign. Paterson, however, who supports Cuomo, wants Sharpton to run against Senator Daniel Moynihan.

Paterson has said he conceives of the new party as a progressive counterpart to the state’s Liberal and Conservative parties. That is, it would function as a pressure group on the Democratic Party, pushing for the nomination of more liberal candidates by the latter but not breaking from it. Other grassroots African-American activists are talking about a real break from the Democrats, but it’s too early to tell whether their discussions will lead to any concrete results.

I. Racist Campaign, Feeble Response

Why did Dinkins lose? It’s important to remember that his margin of victory in 1989 was very narrow. A lifetime clubhouse politician, he inspired little enthusiasm among African Americans as an individual, representing instead the possibility of putting to use Jesse Jackson’s phrase, “a Black face in a high place”—a goal to be pursued but a certain ambivalence. Nor did Dinkins’ prior career provide much incentive for voters of other nationalities to believe he would change their lives significantly for the better. His tenure in office bore out voters’ hesitations; thus Dinkins could not afford the slightest shift in his bases of support.

The most commonly cited reason for his loss this year is the racism of white voters, and in particular the unusually large, and almost all white, turnout from Staten Island. By itself this borough provided the margin of victory for Guiliani. Eighty-two percent of Staten Island voters went for him, and total borough participation was higher than normal because of enthusiasm for a referendum on Staten Island secession from New York City that was also on the ballot. The bitter irony for Dinkins’ supporters is that Staten Island seems to be having its cake and eating it too, ridding the city of a Black mayor while voting to evade any future entanglement with that city’s problems.

The issue of crime was the core of Giuliani’s campaign, as he harped on media accounts of drug-related murders. Media coverage of shootings in Black and Latino neighborhoods has swelled this year; both the local Fox channel and New York Newsday, for instance, are now running series entitled the “Guns of November.” In playing to white voters’ fears of crime both the media and Giuliani ignored the fact that most victims of violent crime are Black, and that Dinkins had dramatically increased the number of cops on the beat, at the expense of social programs. Dinkins pointed proudly to his hiring of tens of thousands of cops, but failed to take on the thinly-veiled racism of the anticrime message, arguing instead that he could be just as tough on crime.

The media also gave Giuliani an edge with its attacks on Dinkins’ competence, not only during such crises as the Washington Heights and Crown Heights affairs, but also for his handling of more routine New York phenomenon such as corruption in the Parking Violations Bureau and inept asbestos removal in the city’s schools. Dinkins was attacked for allegedly appeasing “rioters” who protested against a cop murder of a Dominican youth last summer.

He was also criticized for not allowing the NYPD to use its usual brute tactics to crush a riot in Crown Heights that same summer by Blacks against the Lubavitcher Hasidim. The latter have regularly received favoritism in city contracts and police protection; unfortunately the targets of Black resentment have not been the elite doling out the favors but the Hasidim themselves, who are a relatively poor community—and one whose overt racism helps the elite deflect resentment from their own doorsteps. The Hasidim have become the targets of anti-Semitic attacks by some Blacks; during the riots, anti-Semitic chants were common, and a young Hasid was stabbed to death.

The December 12th Movement, Sonny Carson and C. Vernon Mason and some other Black radicals have encouraged at best and ignored at worst this anti-Semitism, and have in addition egged on anti-Korean racism; a protest against an assault by a Korean grocer against a Black youth was escalated by these forces into a racist campaign against all Koreans—a campaign that Dinkins was slow in criticizing.

Supporters of Dinkins argued that the problems of corruption and mismanagement were either inherited from previous administrations or too entrenched to fix in one term; they also argued that Dinkins handled the rebellions properly by being a calming rather than repressive figure. Thus his supporters’ main argument for re-electing him was that he would be a quiet maintainer of the status quo. Dinkins was perceived in 1989 as someone who would calm the city after the open racism of the Koch years—not as someone who would dramatically advance Black goals. He did remove some of the worst excesses of Koch—while on occasion, as in the Tompkins Square police riots and the Washington Heights affair (see ATC 41)—giving free rein to the bully-boys of the NYPD. This record was not good enough to inspire Black voters, for whom the status quo means routine oppression at best, misery and death at worst.

The media also, in the last two weeks of the campaign, attacked those who said that whites might vote against Dinkins for racist reasons. Clinton, at a campaign appearance for Dinkins, criticized voters who “don’t consider voting for someone who doesn’t look like them;” the local media were immediately filled with hysterical denuncations of Clinton’s statement as fueling “Black racism.” No parallel critique of Giuliani’s racism was forthcoming from the media; at most New Yorkers were quoted as expressing fears he would be “mean” or “nasty” in his governing style.

Nor did the media take on probably the key figure behind mobilizing Giuliani support, Bob Grant, one of a number of openly racist radio talk show hosts whose filth has become an increasingly noxious presence on New York airwaves.

A newcomer to New York could look at the neighborhood voting breakdowns and identify without fail which areas are Black and which white. BedfordStuyvesant went 26,700 to 700 for Dinkins; East New York 22,300 to 1,400 for Dinkins; Howard Beach and the Rockaways went 30,000 to 5,800 for Giuliani; Bensonhurst and Gravesend went 23,300 to 3,000 for Giuliani. Only a handful of neighborhoods in the city were evenly divided—especially those with mixed Black and white residents, or in Latino or Asian-American neighborhoods. (Dinkins’ Latino vote slipped from 65 to 60%.)

As a former high-profile prosecutor Guiliani was well-suited to be at the center of a racist law-and-order campaign. He formulated the U.S. policy of interning Haitian refugees at Guantanomo before deporting them back home; he also coordinated a series of prosecutions of Mafia chiefs in the mid-1980s which (for the tenth time this century) “broke the back” of the Mafia. (Ironically in 1989 these prosecutions lost him quite a few votes in Italian areas of Brooklyn.) He also spearheaded the early stages of the government’s RICO suit against the Teamster bureaucracy.

Nonetheless Giuliani has shown himself quite capable of encouraging criminal activity. During the cop not in front of City Hall in the summer of 1992 he egged on tens of thousands of drunk cops rallying against the proposed Civilian Complaint Review Board designed to monitor police brutality. As hearings on the Board went on inside, Giuliani led the cops in chants of “Bullshit” in reference to Dinkins’ support for the proposal. Cops at the rally closed down the Brooklyn Bridge, called Councilwoman Una Clarke, who was trying to get past them into the hearings, “nigger,” and chanted against Dinkins “get rid of the washroom attendant.” The cops also stormed past police barricades on the steps of City Hall, stopping just short of breaking into the building.(1) The majority of these cops, as is true of the force in general, were not city residents but live on Long Island or in other suburbs. During the campaign the cop union, the PBA, ran ads attacking Dinkins.

This police force that Giuliani promised to turn loose if elected underwent during the campaign a time-honored New York ritual of exposure; every twenty years in the city hearings are held outlining police corruption and brutality, following which nothing changes. This September the Mollen Commission hearings heard about police participation in drug sales, property thefts, tipping off drug dealers and providing them with protection. The most graphic witness was dubbed by his fellow cops “the Mechanic” because he regularly “tuned-up,” i.e. beat up, any Black citizen in the vicinity of drug raids. These hearings never became an issue in the campaign; Blacks who supported Dinkins most often cited fear of stepped up police brutality under Giuliani as their main reason for going to the polls, but Dinkins did nothing to use the Commission findings to maximize their turnout around this issue.

On Election Day itself there were massive violations of voters’ Tights at the polls, as police in several instances intimidated people of color. Cops put up phony Dinkins posters in mostly Dominican Washington Heights, saying the INS would be checking voters’ documents at the polls. In some cases police themselves asked Latino voters for their passports. Dinkins held an Election Day noon press conference complaining about these incidents (Attorney General Janet Reno says they will be investigated).

II. Black Abstention, Uninspired Voters

Racism was half the equation in Dinkins’ loss. The other half was abstention of those whom progressives thought should be his natural voting base: Blacks, other people of color, women and working-class people.

The Black vote for Dinkins was roughly the same as in 1989—that is, almost all Black voters went for Dinkins, but many other slacks stayed away from the polls. Given the narrowness of Dinkins’ victory in 1989, this dropoff, however marginal, was fatal; Dinkins could only have won by maintaining his support in all sectors of his 1989 base and making at least a slight improvement in one of those sectors. Throughout the campaign there were reports of apathy in the Black community, even of a lack of enthusiasm on the part of Dinkins campaigners. The thrill of electing the city’s first Black mayor in 1989 was no longer a factor, and there was little fervor to fight for retaining a man who was perceived in incident after incident as having compromised with the city’s elite at the expense of the Black community.

Dinkins increased his slack total by only 22,000 votes—not enough to make up for the white shift toward Giuliani. According to Bob Fitch he gained votes from middle-income Blacks while losing votes from working-class Blacks: “it was in the ghettos of Harlem and central Brooklyn, not simply in Staten Island, that Dinkins lost the election” (Village Voice post-election issue, November 10, 1993).

The Latino vote, while still heavily pro-Dinkins, was also not an inspired one. Giuliani tried to snatch away this vote by picking Puerto Rican politician Herman Badillo as his running mate, a ploy that fell on its face. Nonetheless, Latinos who fought alongside Blacks during the Dinkins years to expand various multicultural causes felt little enthusiasm in campaigning for a man who regularly ignored or toyed with many of those causes. A couple weeks before the election, for instance, the National Congress for Puerto Rican Rights held a press conference outside City Hall to criticize Dinkins for ignoring the Latino community. To make matters worse the state Democratic Party issued a flyer portraying Latinos before Dinkins as living in squalor, an image rightly characterized as insulting.

Nor did Dinkins’ handling of negotiations with the majority Black and Latino municipal workforce generate much enthusiasm. Michael Tomasky in the post-election Village Voice recalled how in the first two years of his administration the two biggest city unions, AFSCME DC 37 and Teamsters Local 237, “stood on the steps of City Hall and denounced the mayor as a sellout.” These unions, along with others, sponsored a huge contract demonstration against the mayor.

Says Tomasky: “Even Dennis Rivera, Dinkins’ most ardent union backer, said on a television program in 1991 that unless Dinkins changed his priorities, Rivera couldn’t see supporting him in 1993.” Everyone knew Rivera was bluffing, of course, but the experience had lasting consequences. “That disaffection carried residuals last week, in the form of lower turnout and enthusiasm,” said Ed Ott, political director of CWA 1180, a smaller municipal union; “You [Dinkins] never inspired us, stirred us, called us to the barricades.”

(On the other hand, when the majority white UFT refused to endorse Dinkins because the latter backtracked on promises for a better contract this summer, many Black members were outraged that the union would risk throwing the election to Giuliani.)

Dinkins also passed up opportunities to appeal to white working-class areas of the city—including Staten Island. Edmond Volpe, head of the College of Staten Island, was fired by CUNY Chancellor Ann Reynolds, in retaliation for his opposition to her plan to cut courses and majors throughout the CUNY system. Hundreds protested in favor of Volpe. The college is also at the center of a lawsuit charging discrimination against Italian-Americans in enrollment, hiring and promotion in the CUNY system.

Dinkins’ policies evoked a similar ambivalence among feminist activists and lesbian, gay and bisexual groups. On the one hand, Dinkins issued a number of progressive statements, and took a few halting measures,in support of demands for services and protection from discrimination on behalf of these groups. On the other hand, he repeatedly stalled, hesitated and sometimes opposed their demands, for instance around needle exchange, protection and funding for abortion clinics and women’s health services in general. When the Irish Lesbian and Gay Organization protested their exclusion from the St. Patrick’s Day Parade, Dinkins had over 200 marchers arrested (only to drop all charges the very week before the elections).

Similarly, in contrast to the Lubavitchers, who were against Dinkins even in 1989, the other Hasidic sect, the Satmai were pro-Dinkins in the first election but switched allegiances in resentment against his support for an incinerator in their neighborhood and other grievances around housing and economics. As with the CUNY issue, the incinerator grievance has ignited protests among New Yorkers of all nationalities. opposition to incinerators and other environmental hazards has sprung up among Blacks and Latinos in West Harlem, the Bronx, and Brooklyn; Staten Island’s resentment at use of their Fresh Kills site as the dumping ground for the city’s garbage could have been linked to this movement. There was no way, of course, that Dinkins, given his attachment to local business, was going to facilitate such a linkage.

III. Economic Background to the Election

During the 1980s the service sector was going to save the city, whose elites had consciously deindustrialized its previously huge manufacturing base (see Bob Fitch, The Assassination of New York, Verso, 1993) With the most recent depression, the service sector jobs added in the ’80s are mostly gone. The city’s poverty rate, which was only two-thirds of the national average in the 1960s is now double that of the rest of the country. Social services and infrastructure for the victims of this renewed poverty are disappearing at an accelerating rate. For instance, says Fitch, “Peoria, with a population of 100,000 produces more new housing units a year” than New York—yet 60 million square feet of commercial space constructed during the 1980s sits vacant.

Fitch points out: “The two candidates tacitly agreed to take jobs, poverty, the budget and taxes out of the thick of the campaign.” New York is the “youth unemployment capital of America. Even white youths here are far less likely to have jobs than Black youths in the rest of the country” The city’s economy is run by and for the 700,000 commuters “epitomized by Long Island currency trader George Soros, who earned $650 million last year—more than the poorest 100,000 households in Brooklyn combined—and paid local taxes at the rate of less than half of I per cent.” (Soros made millions on the fluctuations in Germany’s Deutschmark this summer, and has made millions in financial transactions involving the restoration of capitalism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union).

Dinkins said almost nothing about any of this during the campaign, aside from mumbling a few words about some modest jobs programs, which few of the city’s working poor took seriously. He threw a few sops to workers fighting to save their jobs, such as the belated support given to workers at the Taystee Bakery, (who demanded that he revoke tax breaks given to the company, which had taken the money and then closed up shop). The significant tax breaks, however, were those Dinkins granted on an almost weekly basis to hugely profitable firms threatening to flee to New Jersey or other low-tax havens. New York’s banks have continued to be immensely profitable during the city’s continued economic stagnation; Dinkins was not about to cam paign against them, blaming instead federal budget cuts for all of New York’s woes. This approach got some people on the buses down to the Save Our Cities March which Dinkins and Local 1199 so heavily promoted; it did little, however, to convince New York voters that Dinkins would or could do anything to save their jobs.

This policy of appeasing the rich paid some limited dividends for Dinkins. During the campaign he maintained his support from the wing of New York’s ruling class that had backed him in 1989, which contributed hefty sums to his campaign (leading donors included liquor magnate Edgar Bronfman, real estate developers Bruce Rather and Jack Rudin and Jonathan Tisch, and bankers Felix Rohatyn and James Harmon). Dinkins actually improved his vote among those with income over $100,000, going from 19% in 1989 to 35% in 1993. He also secured once again the endorsement of the newspaper of the liberal wing of the ruling class, the New York Times.. Yet overall Giuliani still got the mority of the wealthier votes—in fact support for Giuliani went up continually the higher you went up the income scale (a scale which in New York is directly correlated with white skin color).

IV. A National Trend Against Black Mayors?

Several commentators have contrasted Dinkins’ record to that of Chicago’s Harold Washington, who increased his vote total the second time around He implemented programs to increase services for working-class Chicagoans of all nationalities at the same time that he gave Black residents the sense that they were beginning to make permanent headway in ending their exclusion from political power. Between 1983 and 1987 Washington increased his total from 51 to 54%; he did so first by boosting his base among Latinos (the Puerto Rican vote went from 67 to 85%, Chicanos from 50 to 65%). His “white liberal” (i.e. middle-class) vote went from 33 to 45%(2) Most significantly in contrast to New York the “white ethnic” (i.e. working-class) opposition to Washington dropped dramatically: from 30,000 per ward to 20,000 (see Michael Tomasky, Village Voice).

Is David Paterson right? Is there a national trend against Black mayors? Several Black mayors lost this year (Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, Washington and Hartford among others). Dinkins was the only one to lose after one term; on the other hand, he was also the last elected, i.e. he was elected just in time to be part of the national wave of defeat for Black mayors.

In the 1970s several factors combined to begin the ascent of Black politicians to local office; local Democratic Party machines were weakened, the national Democratic Party sought to co-opt Black Power sentiment; and cities themselves became relatively less important as capital accelerated its century-long flight toward the suburbs and rural areas for construction of new plants.(3) The combined strategy of co-optation and repression demobilized the Black movement in the 1980s, facilitating a more general turn toward the right in U.S. politics in that period; now in the 1990s the ruling class—or at least a part of it—seems to feel even Black figureheads may not be necessary to keep the peace.

Other indications of this trend on a national scale include the recent Supreme Court outlawing electoral districts in North Carolina that had been shaped to increase Black electoral influence, as well as Clinton’s abandoning of Lani Guinier and his continued refusal to fill several major federal civil rights posts.

V. Seeds for Future Resistance

In the meantime, everyone on the left, both those who advocated voting for Dinkins and those who saw him as not meriting their support, expect increased cutbacks and repression under Giuliani. In addition to promising massive drug sweeps against street-level dealers (a policy which most officials in other cities and the majority of criminologists say is pointless and ineffective), Giuliani is promising to privatize city hospitals and lay off city workers. The left and popular movements in the city, confused and dormant under Dinkins, will now have to revitalize themselves and tighten their links with each other.

Doing so means overcoming the demobilization, disorganization and fragmentation among city movements—all of which were present before Dinkins, but were aggravated during his tenure in office as leaders of most movement groups waited for him to fulfill his promises. Thus Newsday’s day-after sarcasm was unfortunately all too true, predicting that “a Republican’s cuts in social services seem certain to arouse the ire of an advocacy community that stood strangely silent during similar cuts these past four years.” For instance, four years ago Dinkins promised health benefits for domestic partners of lesbian and gay city employees, and only fulfilled the promise on the eve of this year’s election. Radical lesbian activist Donna Minkowitz, in the Voice, attributed his decision to finally come through on this pledge in the following terms: “If there is any silver lining for queers in Giuliani’s victory, it is that a heartbreakingly close election provided what four years of a gay-friendly mayoralty had not: a reason for David Dinkins to keep his promise.”

Progressive leaders in New York, while repeatedly frustrated by Dinkins’ failure to move fast enough—or sometimes at all—kept cutting him slackm the hope that he would come over to their side. This approach not only demobilized people, it hindered recruitment to, and organizational consolidation of, the city’s movements.

Yet these movements exist in surprising diversity. The Citywide Coalition to End Police Brutality, formed during last summer’s CCRB hearings, still exists—a landmark where such coalitions almost always die within weeks after the latest police atrocity fades from the news. The Network of Black Organizers has received a shot in the arm from recent organizing done out of Manning Marable’s new Institute on African-American Studies at Columbia University. The Women’s Action Coalition and Women’s Health Action Mobilization, ACT-UP and Queer Nation have hung on through tough times, if in a weakened state.

The city’s working class similarly displays small but impressive signs of resistance. Workers in Chinatown are mobilizing around strikers at the Silver Palace restaurant a new workers’ center on the Lower East Side has been established; Black and Latino maintenance workers in SEIU are beginning to revolt against the shackles put on them by an all-white bureaucracy. On October 20th 300 Black and Latin workers organized by Harlem Fightback rallied for a massive jobs-throughconstruction program.

Earlier in October I attended a demonstration during a one-day strike against the HIP health insurance chain. On the chanting, smiling, whistling picket line of hundreds of strikers—almost all Black women, many of them from the Caribbean—the gap between the available social base for a true radical politics in the city, and the current demobilization, was heartbreakingly apparent The strikers union, 1199, is the most significant and most symptomatic example of that gap; it represents hundreds of thousands of workers, the vast majc:’ women of color, repeatedly mobilized in contract disputes in the last few years. In the political sphere, however, 1199, though paying lip service to the idea of political independence through the New Mority Coalition Party (NMCP) has in practice acted as the mainstay of the Dinkins campaign and the Democratic Party in general. (Dinkins, nonetheless, refused NMCP’s endorsement.)

It’s likely that the initial result of Giuliani’s victory, perhaps for quite some time, will be further demoralization.. But eventually his attacks on services and people’s rights may provoke a renewal of struggle by the city’s impressively diverse array of social movements, a struggle that could provide a realistic context for the construction of a genuinely independent third party. Such a party, rooted in the city’s working-class communities of color, could for the first time in decades present new Yorkers with a real alternative at the ballot box at the same time that it fosters rather than frustrates their mobilization in the streets.

Notes

- After the rally a drunken cop riding the subway tripped a young Black man, Yunus Mohammed, and called him nigger.” After the youth apologized, the first cop began hitting him; Mohammad then slashed the co with a box-cutter, afte rwhich the other cops jumped him, beating him brutally and continuing to do so after handcuffing him, eventually breaking his jaw.

back to text - In contrast white middle-class liberals in New York were repeatedly quoted in the media as agonizing about their being tempted to switch to Giuliani on grounds of competence.”

back to text - Fitch, in The Assassination of New York, describes how the city suffered even more than most cities from the general economic downturn affecting all cities, given the conscious decision of the local ruling class in the last three decades to disinvest in manufacturing in favor of the FIRE sector (Finance, Insurance and Real Estate). New York at one time had more manufacturing jobs than any city in the country; the loss of these jobs, as well as of the service robs gained in the 1980s, is crucial to understanding the city’s racial divisions as well as its crime rates and general social degradation. See also Mike Davis, City of Quartz, and Haki Madhubuti, Why LA. Happened, and Why It Will Happen Again, on parallel trends in Los Angeles.

back to text

January-February 1994, ATC 48