Against the Current, No. 37, March/April 1992

-

Democrats: Road to Nowhere

— The Editors -

Politics of Health Care Reform: Market Magic, Bad Medicine

— Colin Gordon -

Funding the Right: Rhetoric Vs. Reality in Nicaragua

— Midge Quandt -

Politicization in the Nicaraguan Schools

— Michael Friedman interviews Mario Quintana -

Carlos Menem & the Peronists: From Populism to Neoliberalism

— James Petras and Pablo Pozzi -

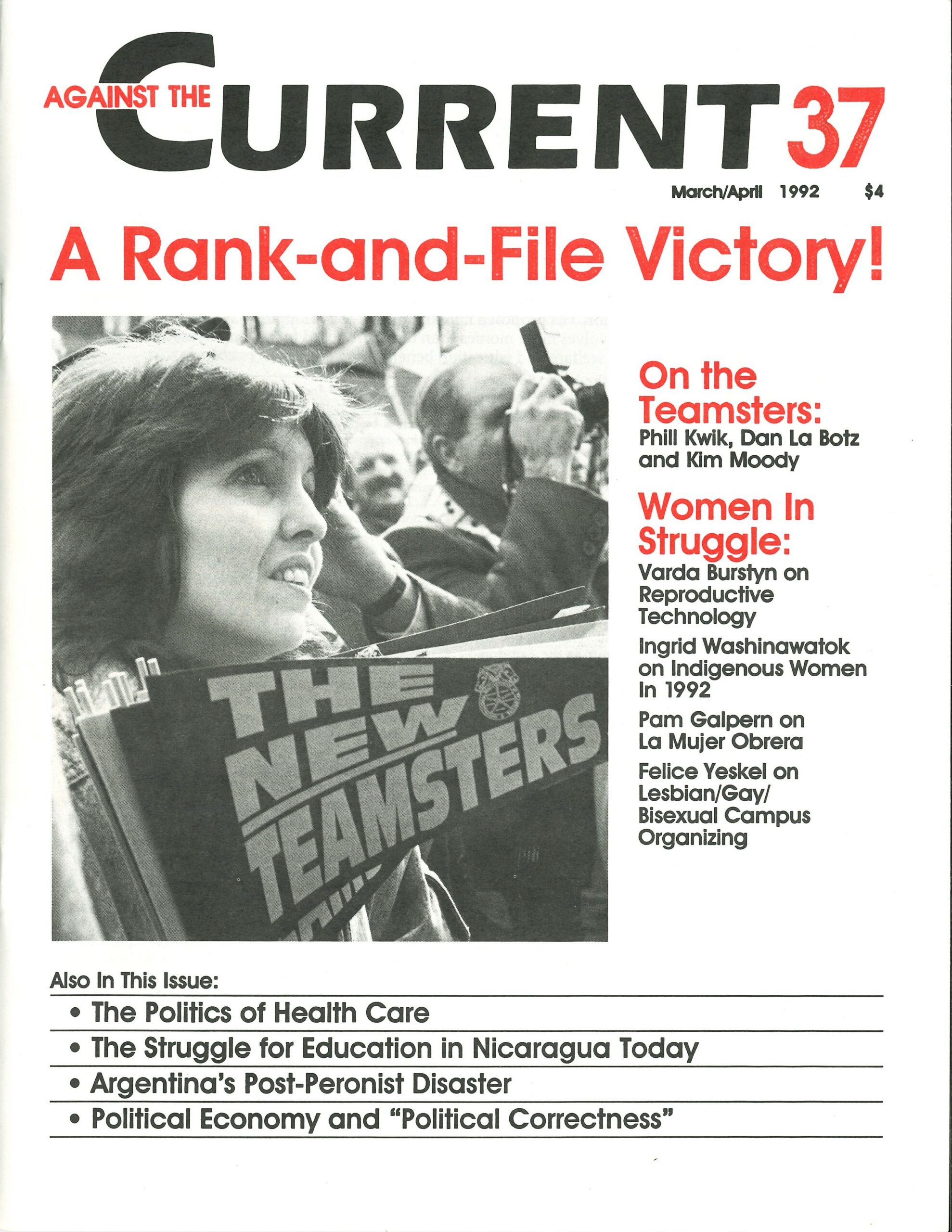

The New Teamsters

— Phil Kwik -

Rank-and-File Strategy Is Vindicated

— Dan La Botz -

Who Reformed the Teamsters?

— Kim Moody -

Political Economy and "P.C."

— Christopher Phelps - For International Women's Day

-

A Feminist Views New Reproductive Technologies

— an interview with Varda Burstyn -

Random Shots: Goodbye Old World Order

— R.F. Kampfer -

The Rebel Girl: Implants, Identities and Death

— Catherine Sameh - For International Women's Day

-

A Notes on Reproductive Technology Terms

— Varda Burstyn -

Indigenous Women 1992

— Ingrid Washinawatok -

Latina Garment Workers Organizing on the Border

— Pam Galpern -

Campuses Out of the Closet

— Peter Drucker interview Felice Yeskel - Reviews

-

Surrealist Arsenal

— Michael Löwy -

Sisterhood and Solidarity

— Marian Swerdlow - Dialogue

-

The Rise & Fall of Soviet Democracy

— David Mandel -

On "Leninism" and Reformism

— Ernest Haberkern - Reviews

-

C.L.R. James' Collected Works

— Martin Glaberman

Michael Friedman interviews Mario Quintana

Mario Quintana is the General Secretary of the Nicaraguan Teachers Union ANDEN and member of the Sandinista Assembly, a governing body of the FSLN. He was interviewed July 22, 1991 in Managua by Michael Friedman, a bilingual high school science teacher in New York. Friedman worked in the FSLN’s paper Barricada Internacional and the Nicaraguan Fisheries Institute from 1982-1987. The transcript has been excerpted by ATC.

Michael Friedman: How has the change in government affected teachers? Mario Quintana First, the government has the idea that those teachers who worked during the ten or eleven years of Sandinista government were causes of student politicization. This has meant that many teachers who occupied positions of responsibility in the Ministry of Education (MED), or simply taught class, have had various contradictions with the Ministry of Education.

Norman Garcia, a member of our National Executive Committee and the Teachers Union’s General Secretary in the Education Ministry headquarters, was fired precisely because of these contradictions. We don’t have a complete list, but we’re sure there are over 1000 cornpaneros who have been fired nationwide. And there are even greater numbers who have not been fired, but have been relocated, including teachers who have been transferred from semi-urban areas to the depths of the mountains.

This affects all teachers’ job security. The government’s economic policy has caused a deterioration in teachers’ wages. There are also problems with respect to pedagogical conditions, since there is practically no budget for maintenance of schools and educational programs.

This government says it is trying to promote an apolitical education. However, this is false. I don’t share the opinion that education can be apolitical. On the other hand, education can certainly be insulated from partisan politics. But they can hardly say education is apolitical when, for example, natural science textbooks, donated by Norway, are withdrawn by the Ministry of Education simply because they speak of the origin of humans.

Insofar as the leadership of the MED is connected to the Cuidad de Dios, which is a very privileged, extremely religious group [charismatic CatholicMFJ, there is political thinking involved. In their public speeches, they claim to want to depoliticize education. Rather, they want to eliminate the revolutionary thought developed during ten years in order to impose their own thinking.

Yes, we should recognize that not Zrevolutionary thought in general, but also party politics, were present inthe previous textbooks and education. Efforts should have been made not to have overloaded the textbooks with the political content they previously had. But the present government is obviously carrying out its political program, and education is an instrument of every government.

MY: What are the main demands of the teachers?

M.Q.: The principal demand has to do with salaries. Teachers’ wages are not enough to cover basic, minimum necessities. Some teachers even have to work two or three shifts, or hold another job, in order to survive. About 80% of teachers are women, many of them single mothers.

Another primary necessity for teachers is related to job security—the right to a position. We are also demanding participation in the formulation of educational policy. What we want is not participation at the top, just for the leadership, but rather a national consultation with teachers as was done when we defined the Goals, Objectives and Principles of the New Education [the Sandinista government education program, drafted in 1983 after a national consultation with all sectors concerned with education—ed.].

M.F.: Are those your only demands? M.Q.: No, there are others, but those are the most important. There are also demands relating to supply of basic necessities and housing. There are many teachers who don’t have a home. We are also seeking to improve conditions for retired teachers—who are receiving so little that some work past their retirement age.

Obviously, we also demand better education in this country, where illiteracy is rising—now over 20%—where 200,000 elementary and high school students can’t go to school because the school can’t absorb them or their parents can’t afford it, where conditions in schools are deplorable and teachers have no materials.

M.F.: Whatd is your plan for struggle?

M.Q.: Our main task is to strengthen the union. No plan will work if it doesn’t have a base to support it.

Training our leadership and membership is very important for us. We’re currently holding a national workshop for our national and provincial leaders. Next weekend I’m going to South Zelaya—to Blueflekis, Pearl Lagoon (on the Atlantic Coast). Other union leaders are going to the Atlantic Coast, to the mining region, while others are going to Rio San Juan to hold trade union workshops, so teachers will know what the union is thinking.

Furthermore, we have to unite with the unions that form the National Workers Front (FN1), not just at the leadership level, although that’s important, but it’s even more important that teachers join with union leaders and workers in enterprises, unions and neighborhoods in their territory.

M.F.: Could you discuss how you’ve related to parents and teachers?

M.Q.: They’re a very important part of our struggle. We have direct and permanent communication with students, and also student leaders. We have to admit that there are currently problems with that communication, sometimes because of our leadership and sometimes because of theirs. But there is a permanent effort to try to maintain communication between leaders so we can support each other.

Communication is somewhat more difficult in the case of parents. There is a National Parents Organization, but in truth it isn’t fully functional.

M.F.: What were the causes and results of the April-May 1991 teachers’ strlke?

M.Q.: In our fifth congress in 1990, we defined our union’s goals, related to salaries, job security and the Teaching Profession Law. But the Ministry of Education remained intransigent. Teachers didn’t receive their paychecks before the Easter vacation; and when MED paid what they called “salary adjustments” teachers received checks for one cordoba, nine cordobas, ten or fifteen cordobas.

This caused a lot of resentment, and a group of teachers in Managua went to MED headquarters seeking a meeting between teachers and the Education Minister, who refused. In a few days, the teachers’ demands became generalized throughout the country until more than 18,000—over 60% of the teachers—were involved.

We obtained a 25% wage increase, which is not what we or the teachers hoped for, but was an advance in the struggle to improve teachers’ conditions. In political and organizational terms, our organization was greatly strengthened to take on future battles. We drew closer to students and parents.

The new teachers’ unions formed by MED were revealed to be scab unions, since they never joined the struggle. In some places they simply ceased to exist, since they not only didn’t take up teachers’ demands but tried to break the strike through force or divisiveness.

M.F.: What was the level of support from parents and students?

M.Q.: The toughest strikes to carry out are those in education and health, because they directly affect other groups—parents and children in this case. However, from the beginning to the end of the strike, we can say that the majority of parents and the majority of students supported it.

Parents participated in some local and provincial demonstrations, and in our two national demonstrations. In other cases, when teachers occupied schools parents also participated, sometimes providing economic support for the strike.

The students showed even greater belligerence in their support in the final moments, when some problems arose with the strike, and also had their own demands. That was when students, led by the Federation of High School students, FES, occupied the National Palace—in support of the teachers, but also to demand resumption of classes.

FES supported the teachers’ demands, since they understand teachers’ problems with wages and job security. In some cases, experienced teachers who have good relations with the students have been fired, and another person brought in who doesn’t have any experience in education. The students are familiar with these problems, and as are-suit give us their support.

Clearly student organizations face a dilemma. They support the teachers’ demands, but faced with a strike, students also demand to continue with their studies. Although students faced this contradiction, FES gave us their full support, but we discussed it continuously with them. One of our commitments was that after the strike we would make every effort to make up lost class time; and in fact today we are making up by adding extra hours to the school day, teachingon weekends and vacations, and prioritizing certain contents and subjects.

M.F.: I understand that during this strike the Chamorro government was able to sow divisions between parents and teachers. Could you discuss that?

M.Q.: There was a particular situation in one school, the Mexico Experimental Institute, where almost 80% of the teachers went on strike. When the principal realized the majority were on strike, he tried to bring in outsiders to take over their classes.

Teachers, students and parents decided to occupy the school. At that point a group of parents called the White and Blue Association appeared, backed by the Ministry of Education. That group of about thirty parents tried to oppose more than 1000 parents who supported the teachers. They also hoped to privatize the school, which is another policy of the Ministry of Education [this plan was abandoned by MED as a result of mobilizations by teachers, parents and students—M.F.].

M.F.: What does the recently concluded FSLwcongress mean for you as a teacher and trade unionist?

M.Q.: The congress has contributed to a better definition of the relation between the party and the mass organizations. It made clear to Sandinista militants that they can’t impose a program on the mass organizations, they can’t impose anything on the mass organizations that doesn’t come from the rank and file of those organizations.

March-April 1992, ATC 37